© 2024 Craig Carmichael

by Craig Carmichael – November 2024

I’m in a good place to see the northern part of the night sky when it’s clear, on an acreage at 53-½ degrees north in the boonies. Skidegate village 15 Km to the south casts only a slight glow on the horizon between the trees. When I turn out my house lights there are no others nearby.

I think I’m finally visualizing Orvonton, which no one seems to have had a real handle on so far (AFAIK). Of course the Milky Way isn’t a “spiral nebula” shape as astronomers have been describing it. It is visibly in the form the UB describes. The spiral shape astronomers claimed to see in 1935 may (or may not) describe our minor or major sector, or (as I suspect) may simply be an assumption that it must be like spiral galaxies we see from a distance. Astronomers’ distance and size estimates also seem off the mark, since the UB says the Milky Way, the main body of Orvonton, is almost 500,000 light years across the long axis, not around 100,000 as astronomers (who recognize no long and short axes) rate it.

Another indication is that astronomers presently claim the Andromeda nebula is 2.5 million light years distant where the UB says it’s “almost a million”. This means astronomers have the dimensions wrong by a factor of about three, which means they think it’s 27 times as massive as it is (3 cubed) and hence grossly overrate its relationship to the greatly underrated Milky Way. New findings in astronomy are contradicting the simplistic 1935 picture, but logical and consistent conclusions are not so far (2024) being drawn to form a new “big picture” which would doubtless tend to bring UB science and “main stream” astronomy closer together. (Observations of the the Milky Way in the1800s seem to have been at least less misleading than those since 1935! American Cyclopaedia of Knowledge (topic “Star”) described the Milky Way’s structure as “mysterious”, but as “the most complex structure in the known universe” in 1879.)

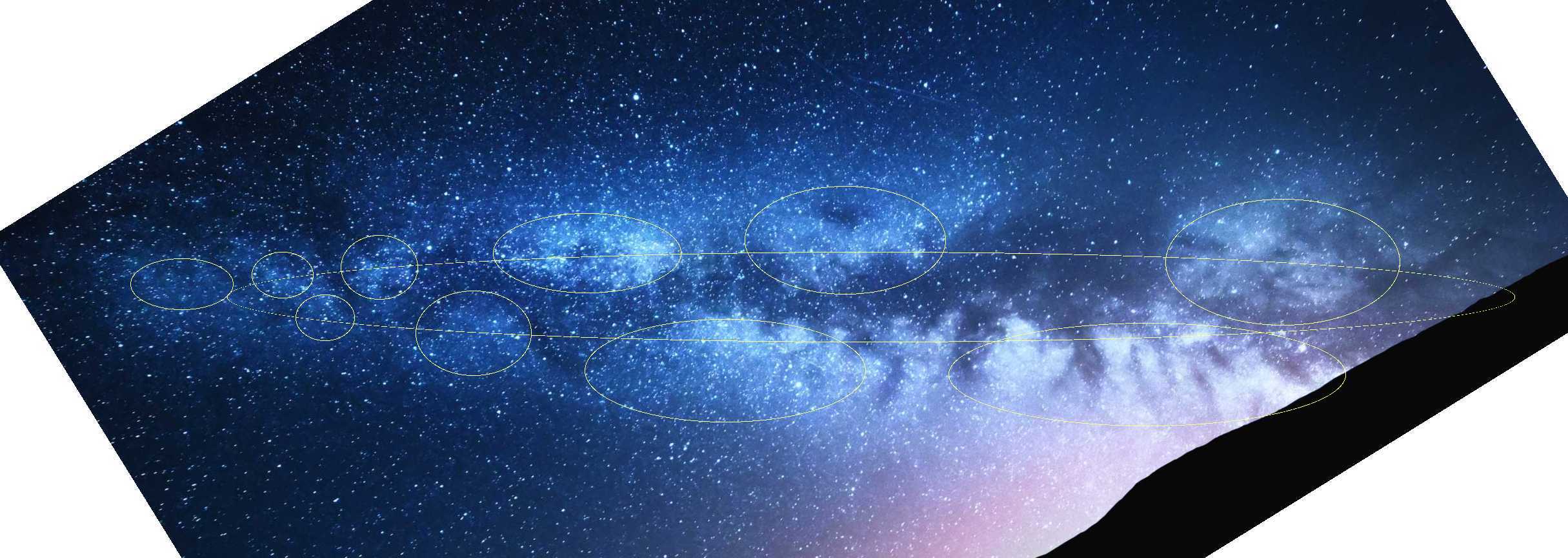

(Note: Notwithstanding that the nearer end of the ellipse is below the horizon, I’ve selected the image below as being the clearest and least overexposed of any I’ve found, while having little distortion into a curve. The strong overexposure of most Milky Way images makes for stunning colors, but obscures a lot of the detail visible here. Even here the haze of nearby stars is still too overexposed to make out the constellations one normally sees in the night sky.)

We see the Milky Way as an odd somewhat broken strip across the sky. Of course we are near to one end of it as well as near the outer edge, so it thins out looking outward, away from the center. When I look northward (here at left) it seems to “peter out” around Cassiopeia or a little beyond, and southward from there it splits into two bands going into Cygnus and beyond. Why does there seem to be a dark band in the middle? Astronomers (IIRC) think there’s gas clouds obscuring the center of the galaxy. I say it’s because there are no concentrations of stars there. They are concentrated instead on each side of this void (here above and below).

Back to UB P. 167, the “Milky Way” or main body of Orvonton is (not exact quotes[1]) ‘a watchlike, elongated circular grouping whose length is much greater than the width, and the width is much greater than the thickness.’ and ‘If we could see it from above, we would immediately identify the ten major sectors’… presumably the “numerals” on the watch. So it is a thin, elongated donut, but the outline of the donut is something of a dotted line instead of solid.

Here is the key: While the UB makes no mention of it, we have simply assumed we must be seeing it directly from on edge so that it should look flat. In fact, we must be slightly above or below the central plane of the donut, so we see two bands side by side, the near one (here below) and the far side (upper). The UB notes that (as of the time of writing) our astronomers had roughly identified eight of the ten major sectors[2], which is a good indication that we aren’t right in the center of the plane, or else more of the sectors would probably be hidden behind other ones and be indistinguishable from them.

In addition, we know that we are far off to the side near one end of this giant ellipse – perhaps somewhere in the ground glow in the image. So to the north (left), we are looking at the far end where the most distant major sectors, around 400,000 light years from us, show only as faint patches. To the center and right (and here below the horizon), we see the nearer end more brightly and in more detail.

Looking southward from Cassiopeia and into Cygnus and beyond, nearby major sectors apparently split off to the left (here below) and more distant ones are to the right (above). Each major sector is observable as a patch of stars, but the overall form is from our perspective a very narrow ellipse (yellow) – two lines of stars that meet at the ends. Being that we are near one end and on one side, there is no reason the two bands and the ellipse overall should look symmetrical to us.

I’ve circled what I tentatively identify as major sectors, but the two circles shown on the lower right are probably both part of our own major sector, Splandon. Although I can’t make out the constellations, they and the thin curving line of features seeming to extend into the center of the main ellipse may be parts of the “two stupendous stellar coils” UB 15:3.5 of our minor sector in constellation Sagittarius.

I make no claim that I have it all figured out, but as a general outline it seems to match the UB description of Orvonton much better than anything I’ve seen so far.

¶ References

“… form a watchlike, elongated circular grouping of about one seventh of the inhabited evolutionary universes.” “…the breadth being far greater than the thickness and the length far greater than the breadth.” “The number of stars and other bodies decreases away from the chief plane of our material superuniverse.” UB 15:3.1-3 ↩︎

“Of the ten major divisions of Orvonton, eight have been roughly identified by Urantian astronomers.” UB 15:3.4 ↩︎