© 2009 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

Following Jean-Noël Robert, the ancient writings on geography that have come down to us can be classified into three types:

- descriptions of itineraries, an example of which would be the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea”;

- works of physical and human geography, such as those of Herodotus, Polybius, Strabo and Pliny the Elder;

- and mathematical treatises, such as those written by Eratosthenes, director of the library of Alexandria at the end of the 3rd century BC

How did Jesus’ contemporaries view the Earth? What physical worldview did peoples like the Jews and other peoples under the dual influence of Rome and the East have?

Basically, the theories that had gained the most success at that time were those of Eratosthenes.

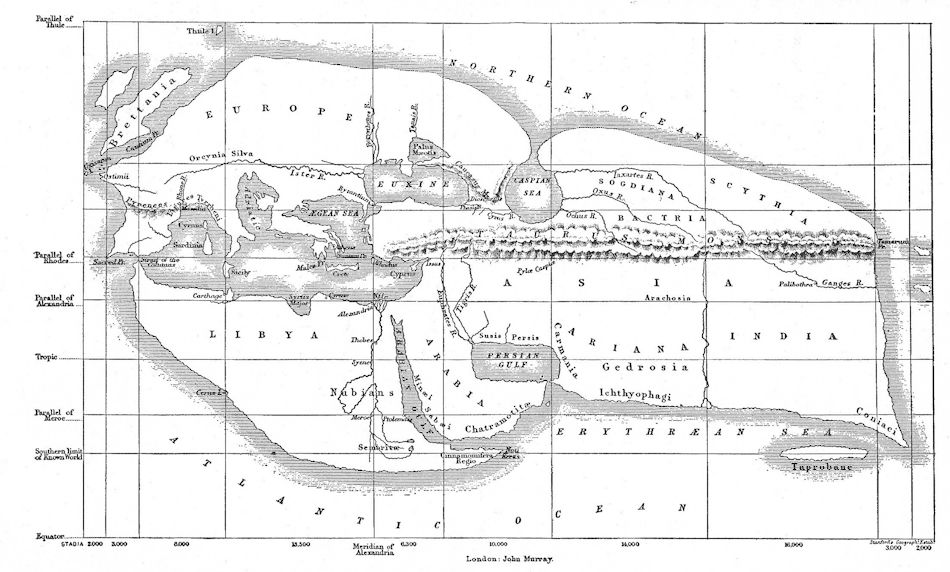

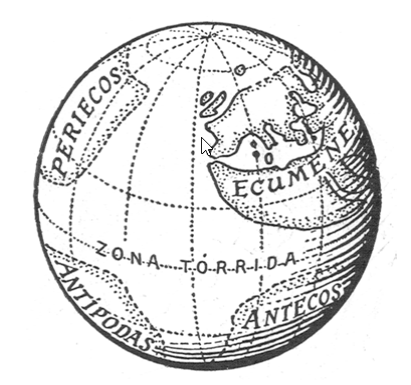

For Eratosthenes, who had calculated the circumference of the Earth, the globe was divided into five parts: two glacial zones situated at each of the poles, a torrid zone between the tropics and two temperate zones between the torrid zone and each of the glacial zones. On this globe, the inhabited earth formed a single, vast continent situated in the northern hemisphere, mainly in the temperate zone, and completely surrounded by the sea.

These theories were also expanded by those of Crates of Mallos (around the middle of the 2nd century BC), who was director of the library of Pergamon, rival of that of Alexandria.

The great difference between the Earth as seen by Eratosthenes and that imagined by Crates lay in the fact that the latter assumed—freely—the existence of other worlds (probably three) situated around the one described by his rival. Of these inaccessible worlds, one was situated in the centre of Eratosthenes’ world, that is to say south of the equator, and the other two on the other side of the globe, arranged like the first two at either end of the equator. The emerged lands would thus give the impression of being separated by arms of the sea in the form of a cross and completely surrounded by water. Crates also hypothesized that some part of these other worlds might be inhabited, for example the areas bordering the tropics where the “Ethiopians” lived. (The word, which etymologically means “burnt faces” in Greek, did not designate in ancient times the inhabitants of a particular country, but applied to all those with a tanned complexion.)

As an indication of the popularity of these theories on the arrangement of the continents, we have a panegyrium of Messala, written by an unknown young poet (probably Tibullus, who belonged to the circle of the consul of 31 BC):

The Earth is suspended in the air that surrounds it on all sides and forms a globe whose whole is divided into five zones. Two of them are perpetually ravaged by a glacial cold, shrouded in darkness; the waters that begin never reach their course, but harden and become thick layers of ice and snow because the Sun never sends its rays towards them. The central zone is subject to the heat of Phoebus, both in summer when it approaches the Earth while crossing the sky and in winter, when it accelerates its pace to put an end to the days; in addition, the ground does not rise with the passage of the plough, there are no sown fields that produce crops or pastures on the land; the gods, Bacchus and Ceres, do not visit these fields and no living being inhabits these completely burned regions. Two fertile zones extend between these and the glacial zones, ours and the corresponding one in the other hemisphere, both similar and tempered thanks to the two climates that surround them at both ends, mutually neutralizing their influence; peacefully, the year offers us its seasons; the bull has learned to submit its neck to the yoke; the vine, flexible, to raise its branches; the fields provide each year their ripe harvests, the earth is full of iron and the sea of bronze; the cities rise surrounded by walls.

This poem depicts the five zones of the Eratosthenes system. Virgil gives an identical description in his Georgics (231-258), a vision of the world that would not be slightly modified until the 2nd century AD.

The Roman vision of the known world was centred mainly and with some precision on the Greek world. Eratosthenes attributed the Asian continent a small surface area, so that there was not a great distance by sea between the eastern coasts of India and the Strait of Gibraltar. Seneca (Natural Questions, I 13) judged that only a few days were needed to reach India from Gades (Cadiz). This was much later favoured by Christopher Columbus’s voyage.

Cartography is a means of describing the Earth that is even older than geography; first there were the plans of the Babylonians and Egyptians, but then the Greeks created the first world maps, around 575 BC, following the flat and elongated projection model that has prevailed to this day.

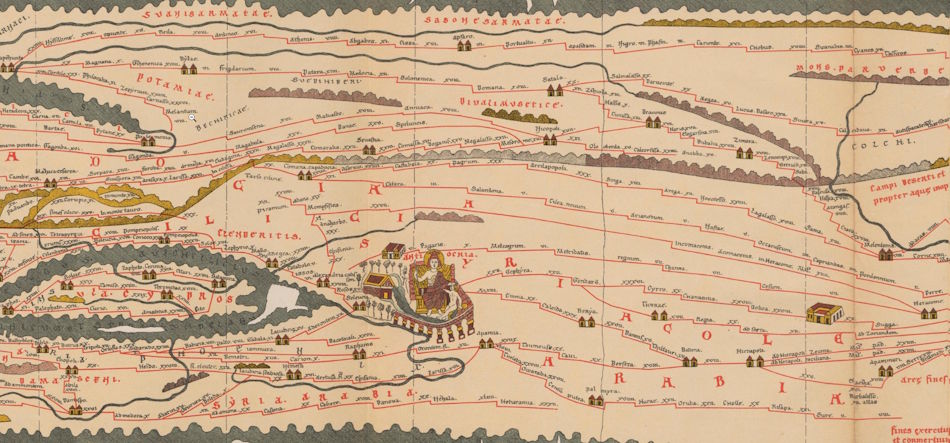

The best-known map is the so-called “Peutinger” map, a medieval copy of a Roman original, which shows the main routes and cities that ran through the empire. Maps were a common Roman teaching aid. They were also used as propaganda by a victor in battle, depicting the territories conquered. The famous and talented minister of Augustus, Agrippa, was commissioned to hang a map of the world on the walls of the Vipsania portico in the Campus Martius, but only the Roman world. There is much debate about this map, which has been lost, and which is known to have depicted the Caspian Sea, Armenia, Media, Parthia, Persia, Mesopotamia, the Red Sea, Egypt, Ethiopia and India, along with the Roman Empire, but it is not known whether it showed Serica. In any case, this map represents the efforts of the emperors of Jesus’ time to make the Roman Empire appear, in the eyes of all visitors to Rome, as the ultimate ruler of the world and architects of world peace.

¶ References

- Jean-Noël Robert, From Rome to China. Along the Silk Road in the Times of Ancient Rome, Herder Publishing, 1993

- Wikipedia, Voyage of the Erythraean Sea

- Wikipedia, Crates of Mallos

- Wikipedia, Tabula Peutingeriana