© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

We can safely say that Capernaum was Jesus’ true home. It is mentioned many times in the Gospels as the setting for interesting passages in his life. Nazareth, of course, was the place of his childhood and adolescence. But, if we stick to the Gospels, the evangelist Matthew makes it clear: at a certain point Jesus decided to leave Nazareth to go and live in Capernaum (Mt 4:13). From that moment on, he came to consider it his own city (Mt 9:1).

But what was this population like in the time of Jesus?

Fortunately, we know the exact location, not because it is populated, but because some wonderful ruins have left clear traces of history.

For my summary I will use two sources (see References). On the one hand, the information on the website of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, the people in charge of the excavations that are being carried out at the site. On the other hand, the opinions expressed in the recommended book Jesus Unearthed, by two good experts in archaeology and evangelical exegesis, John D. Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed. These authors draw up a list of the ten most important archaeological and exegetical discoveries of recent years, and among them they place the discovery in Capernaum of a supposed “house of the apostle Peter.”

In general terms, and this is the important thing, the two sources describe Capernaum in the time of Jesus, based on the archaeological findings found, as a small fishing village with no more than a thousand inhabitants.

And this description seems quite appropriate if we examine the notable absence of remains that reveal a significant urban nucleus.

¶ The location

Capernaum in Jesus’ time was situated in a strategic and privileged location. On the northwest shore of the Kinneret, the Sea of Galilee, about 210 m below the level of the Mediterranean Sea. It was 16 km from Tiberias, 3 km from Tabgha and 5 km from the point where the Jordan River empties into the lake.

The ruins extend some 200 to 300 metres along the coast, and no more than 110 metres inland from the beach. The total surface area is said to be no more than 60,000 square metres.

It has been uninhabited for a thousand years, although some Bedouins who occupied it by building rustic huts called it during this time Talhum.

The Via Maris, or sea road, which the Romans made into one of the roads of the empire, linking Damascus with the Mediterranean coast and the south, passed about 100 m northeast of the remains of the present synagogue. A milestone found from a later period, in the time of the Emperor Hadrian, attests to the existence of the road and its Roman importance.

The site was particularly favourable for fishing. Capernaum was situated on a coastline with an abundance of fish, which extended as far as Tabgha. A great abundance of stoneware and furniture has also been found, indicating the existence of a typical stone industry. Remains also attest to the existence of an industry producing glass vessels, as well as oil (olive presses have been unearthed). Another logical occupation was agriculture.

¶ Public buildings

As for buildings, no Greco-Roman remains similar to those of other more Romanized Jewish towns have been found. No remains of a wall, or of access gates to the city, or any type of defensive building have been found. Nor have there been civic structures such as theatres, amphitheatres, hippodromes, thermal baths or latrines. The thermal baths found at some distance from the central core of the town date from the 2nd century AD, when a larger contingent of Roman troops than the one that must have existed in the time of Jesus was surely established in Capernaum. There is also no trace of basilicas, altars, temples, statues, agoras or markets, or of public inscriptions.

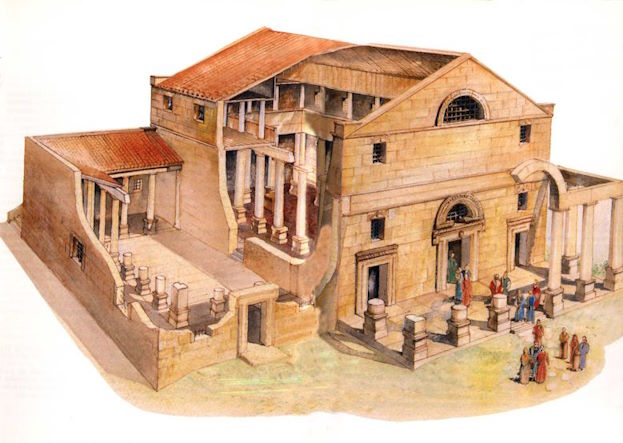

The only two notable buildings in the ruins are an imposing and very well preserved synagogue and the remains of an ancient octagonal church. But both date from the Byzantine period. At the most, in the time of Jesus, there must have been a synagogue of more modest dimensions than the one that can be seen today, situated on the same site. We will return to the subject of the synagogue later.

¶ The streets

According to Reed and Crossan, the street layout does not follow the classic cardo maximus and decumanus of Roman towns. But if you consult the Franciscan website, it says quite the opposite. In my opinion, the Franciscan archaeologists use terms applicable to Roman towns a bit lightly in explaining their findings at Capernaum, mentioning the existence of a cardo, a decumanus, insulae, etc. And although there may have been several important cross streets, the layout of the arteries does not follow an established order as occurred in the gridded Roman towns and which gave rise to the name cardo-decumanus. There are also no stone pavements, running water pipes or sewage drains in the streets, as we find in other Roman towns.

© John Dominic Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, Excavating Jesus, 2001.

¶ The houses

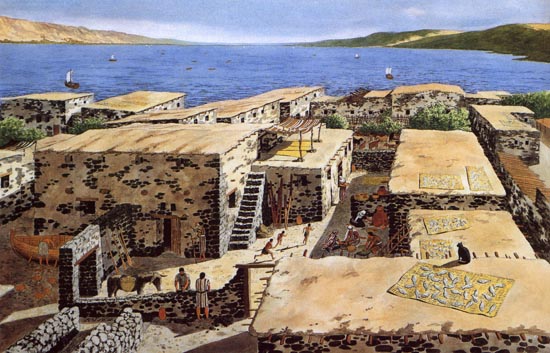

The houses are arranged in a chaotic manner around large central spaces or inner courtyards, with narrow alleys and passageways winding their way in between. There are no remains of atriums or triclinium or formal dining rooms in the houses. The door jambs are not very solid or secure. No amphorae of imported wine or unguetaria, small containers of oil and perfumes belonging to the wealthy, or richly decorated oil lamps have been found in the rooms.

On the contrary, the findings indicate a small, rustic village of humble people dedicated to fishing. Although the Franciscans have found certain domestic units which they have called insulae, they do not resemble the classic Roman dwellings, with a grid layout. Rather, these units are a series of rooms piled up around a single closed courtyard, belonging to a single family. In some areas the alleys between these buildings widened to form small squares, probably places used for mending nets or to have pens for goats or sheep.

This is what Reed and Crossan indicate:

The houses in Capernaum are like those found in other Jewish villages in the eastern Galilee and the southern Golan area, where the usual building materials were the dark basalt of the region, some twisted wooden beams, straw, reeds and mud. […]

The quality of the buildings was poor, […]. The walls were built on a foundation of basaltic boulders; the lower courses that have been preserved were made up of two rows of unworked stones mixed with smaller stones, mud and clay filling the interstices; and instead of stucco or fresco painting, the surface of the walls was covered with a layer of mud or manure mixed with straw, intended to serve more of an insulating than an aesthetic function.

The passage about the healing of the paralytic (Mc 2:4, Lc 5:19) shows a type of roofing in buildings that, as the authors of Excavating Jesus rightly point out, was of little consistency. “Wooden beams supported a thick bed of reeds that protected the logs from moisture, and the whole thing was covered with packed mud for greater insulation.” These simple roofs were normally accessible by means of stone stairs or wooden steps attached to an interior wall. They served as a play area for children, as a drying area for fruit, crops and fish, or as an open-air bedroom in summer. This perfectly clarifies the passage in which the friends of the paralytic make him descend into the room by means of a hole in the roof. It shouldn’t have been difficult to uncover part of the warp and make a hole.

The house, therefore, consisted of a large central courtyard with several rooms leading off. Entire families lived there, including parents-in-law and in-laws (see for example the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law in Mc 1:29). During the long summer months, this courtyard served as a living room, dining room and kitchen, as well as a workshop, garage and storehouse. The kitchen consisted of a simple clay oven and a stone for grinding grain and making flour for bread. Courtyards with agricultural implements have been unearthed, such as large millstones and oil presses powered by mules or oxen. In winter, the entire family slept inside the rooms, usually on the floor, on simple mats, or at most on folding bunks.

Archaeologists have unearthed numerous stone vessels, but not very large: simple jugs, cups or bowls, hand-made or made with the help of a small lathe. The lamps were simple, undecorated or at most had simple floral motifs. The pottery found apparently came from the village of Kefar Hananya in Upper Galilee and consisted of pots, saucepans, water jugs and jars of various kinds. More refined objects such as plates, dishes and cups were not very common.

¶ The synagogue

Today, in the visible ruins, one can admire the remains of a beautiful Jewish synagogue, probably the best preserved remains of such a building in the whole of Jewish territory. However, the building dates back to the 5th century. Curiously, it rests very close to where the remains of the octagonal church from the Byzantine period have been found, which suggests that Capernaum may have been the scene of a growing rivalry between the Jewish and Christian places of worship in more recent times.

This is clearly not the synagogue that Jesus knew. But could it be built on the foundations of the original one that the Master knew? This is what Franciscan archaeologists who have examined the base of the building claim, although Reed does not share this opinion.

Synagogues in the first century were not usually special buildings. In many sites, it has been assumed that some houses were adapted for such use. In other cases, some construction was built, but it was very simple. Crossan and Reed rightly point out that “synagogue” in the time of Jesus did not usually designate a specific type of building, but rather the assembly or meeting place where religious rites were usually celebrated. This place did not have to be a sanctioned or sacred construction for that purpose.

According to Luke’s Gospel, the synagogue as such did exist in Capernaum (Lk 7:1-10), as the evangelist even mentions the benefactor who built it. It is clear that he is not talking about just any house or a public place, such as a square. He is talking about a specific building. This makes me disagree with the surprising interpretations of Crossan and Reed on this issue. For them, the absence of clear and conclusive remains of a synagogue from the first century necessarily implies that there was no such building, even though the synagogue is mentioned even in other passages of the Gospels (Mk 1:21, Jn 6:59).

¶ The Roman garrison

Crossan concludes that the passage in Luke which mentions a “Roman centurion” as the benefactor is not a good translation of either the Greek hekatonarchos or the basilikos of John 4:43-54. That is, the entire passage is mistranslated. The centurion was not a centurion, the soldiers under his command could not have been Roman, and he was by no means the builder of a synagogue. “There were never any Roman officers permanently stationed in Galilee during the reign of Antipas,” the authors state.

However, I disagree with these assessments. He may not have been a centurion, but he could have been a lower-ranking official, and Luke calls him a centurion as a generalization. The point is that he was a Gentile who had a certain esteem for Capernaum because he had served there for quite some time, and he donated money for the construction of a new synagogue.

UB 147:1 is quite clarifying:

On the day before they made ready to go to Jerusalem for the feast of the Passover, Mangus, a centurion, or captain, of the Roman guard stationed at Capernaum, came to the rulers of the synagogue, […]. UB 147:1.1

The expressions “centurion” and “captain” are used interchangeably here. This means that he was certainly not a commander of legions, which is what centurion really meant in Latin terminology, but simply the leader of a small Roman detachment.

But why a Roman detachment in such a modest and uninteresting town as Capernaum? Crossan’s statement is true: there were no regular Roman troops stationed in territory governed by Antipas. Later, there were, and at most, Rome’s attitude towards its province of Judea changed. So what?

One possible explanation for all this, and one that I will use in my book[1], is that this guard actually guarded the road or via Maris, which was Roman property and not Jewish. Most likely they had their garrison near the border of the kingdom of Antipas with that of Philip, his half-brother. Their function, I believe, was to provide some protection to the publicans, the officials in charge of exacting a toll or tribute for the transit of goods between the two borders, and to ensure the safety of the road. Let us consider that this road had a strategic importance: it linked Romanized capitals of that time such as Damascus and Caesarea Maritima.

This role of protector of the publicans could be closer to the people than that of a military detachment in use, performing in a certain way functions similar to those of the publicans, many of whom were Jews. Matthew, the apostle, was precisely one of these publicans. This explains why the “captain” had a house in Capernaum (“Lord, do not trouble yourself. I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof.” Lk 7:6), lived as one more of the community, and was a character loved by the rectors of the synagogue for his donations for the new building.

The Urantia Book makes a clear mention of this garrison in document 129, section 1:

Throughout this year Jesus built boats and continued to observe how men lived on earth. Frequently he would go down to visit at the caravan station, Capernaum being on the direct travel route from Damascus to the south. Capernaum was a strong Roman military post, and the garrison’s commanding officer was a gentile believer in Yahweh, “a devout man,” as the Jews were wont to designate such proselytes. This officer belonged to a wealthy Roman family, and he took it upon himself to build a beautiful synagogue in Capernaum, which had been presented to the Jews a short time before Jesus came to live with Zebedee. Jesus conducted the services in this new synagogue more than half the time this year, and some of the caravan people who chanced to attend remembered him as the carpenter from Nazareth. UB 129:1.7

If it was an “strong Roman military post”, why have no remains of Roman fortifications or camps been found from the time of Jesus? Remains of a thermal baths and fortifications have been found, but they seem to date from the 2nd century. However, what are thermal baths doing next to such an unimportant town as Capernaum? There is evidence that there were troops permanently quartered there after the second Jewish revolt (132-135 AD). In my opinion these troops were simply reinforcing others that probably already existed before.

We will be keeping an eye on future archaeological campaigns in the Capernaum area. I think there is still much to discover near the lake. But in principle, I am leaning towards the idea expressed in The Urantia Book, and which confirms what is suggested by the gospels. There must have been a military camp of some size in Capernaum, probably located near the current remains of some Roman baths, not far from the customs house, guarding the Via Maris road.

¶ The caravan stop

Crossan and Reed do not even mention in passing the possibility of a caravan stop at Capernaum, even though it is known that one of the most popular Roman roads for travellers, the Via Maris, passed through there. Nor do the Franciscan excavators at Capernaum include in their reports any data proving the existence of any building intended to house caravans.

It is surprising that none of the sources take into account that the proximity of the Via Maris would logically entail a huge movement of caravans with goods and travellers.

The misnamed Via Maris, which in ancient times was called the “Philistine Road”, came from Mesopotamia, linked with Anatolia and Syria, and descended towards Egypt using two branches: one headed to the Mediterranean coast through Meggido, and the other continued inland through Dan (Caesarea Philippi), the Sea of Galilee (Capernaum, Magdala and Tiberias) and the Jezreel Valley.

This makes The Urantia Book’s idea that there was a building or esplanade nearby, probably next to the road, that served as a stopping point quite plausible. However, I have not been able to find any data among the sources consulted that attests to the existence of this construction.

¶ The customs house

Another building of singular interest is the customs house or toll house mentioned in the gospels (Mt 9:9, Mc 2:14, Lc 5:27). It is assumed that it would be a building of little importance, so it is easy to understand why no remains have been found that give it away, such as a building next to the road with an unusual number of coins under the floor. This building, as I have already indicated, it is logical to imagine that it had an adjacent guardhouse to house the Roman soldiers in charge of protecting the money from the collections.

¶ Conclusions

Archaeological excavations and expert analysis are shedding light on what the Jewish environment in which Jesus lived and what his daily life by the Sea of Galilee may have been like. However, an examination of the excavation plans shows that only a small area of the entire potential site has been systematically excavated. I believe that future campaigns will bring to light new and interesting discoveries.

¶ External links

¶ References

-

John D. Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, Jesús desenterrado (original in English: Excavating Jesus), Editorial Crítica, 2001.

-

Website of the sanctuaries guarded by the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, which includes Capernaum.

-

Archaeological sites at Capernaum. (The original link is broken but a copy can be accessed at Internet Archive.)

¶ Notes

This book is the novel «Jesus of Nazareth», a biography about the Master based on The Urantia Book that is in preparation by the author. ↩︎