© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

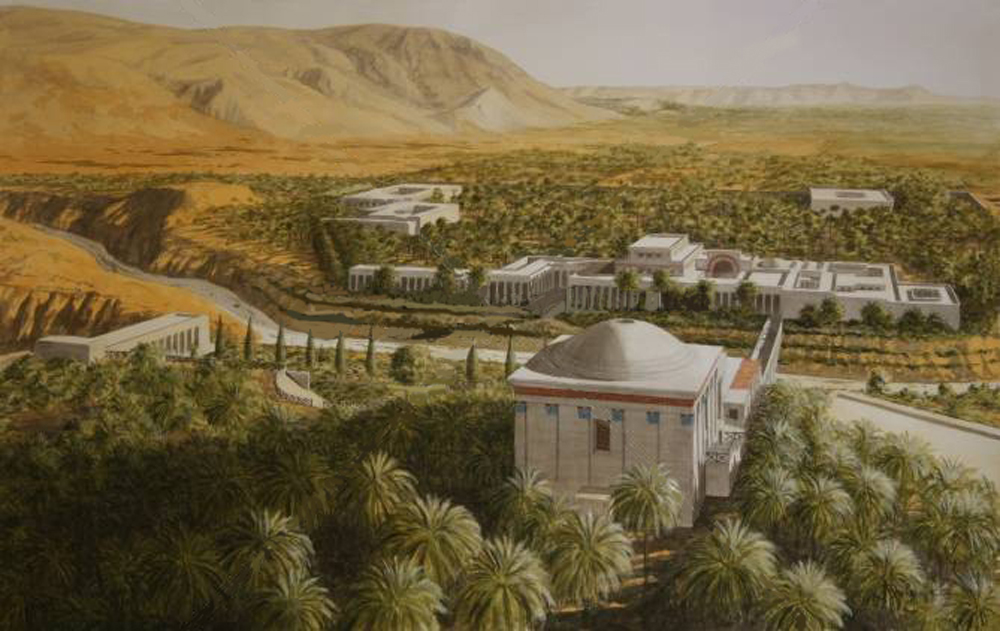

The city of Jericho was given by Mark Antony to Cleopatra as a gift, but after their suicide it was repossessed by King Herod, who was given it by the new Emperor Augustus. The king used it extensively as his winter residence, building a hippodrome to entertain his guests, aqueducts to irrigate the area beneath the nearby cliffs and to supply his winter palace with water. It was at a pool in Jericho that Herod gave the order, apparently according to Flavius Josephus, to murder his wife’s brother Aristobulus III at a banquet hosted by Herod’s mother-in-law, Aristobulus’s mother.

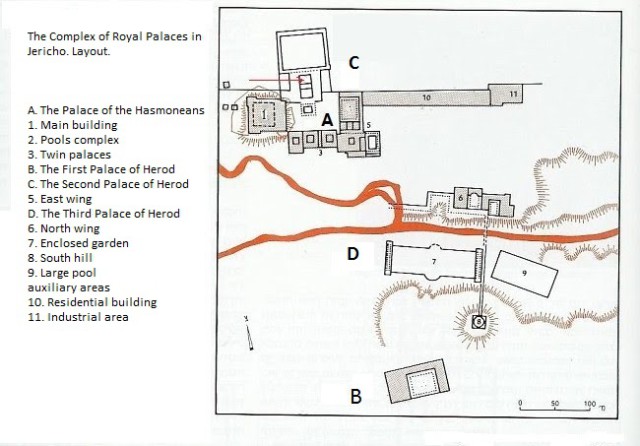

The town was situated near the entrance to the Wadi Qelt (known at that time as Nahal Perat), where Herod built a fortress called Kypros, in honour of his mother. During his long reign, from 37 to 4 BC, Herod managed to build three separate palaces on the same site, which ultimately functioned as one. It appears that in Herod’s early years (37-31 BC), the Hasmonean family continued to use their palace at Jericho.

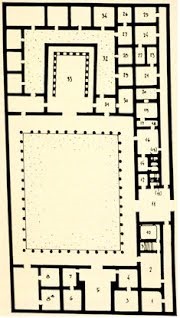

Herod built his first free-standing palace at Jericho (probably c. 35 BC), not far from the Hasmonean, south of Wadi Qelt. It was a large rectangular building (84 x 45 m), built on three sides of a peristyled courtyard. It included a large triclinium, various service rooms, a Roman-style bathhouse, and a ritual bath. Despite the free placement, resembling a Roman house similar to those at Pompeii, this layout may reflect Herod’s political insecurity (35-30 BC), when Jericho was taken from him and given to the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

Herod’s second palace (ca. 25 BC), was built as an open complex, exposed to the surrounding landscape. It was built on top of the ruined Hasmonean complex, following the latter’s destruction by the earthquake of 31 BC. The main wing of the palace (the E wing) was built to the NE of the ruined twin palaces. It was structured on two levels: the upper one with a pool and servants’ quarters was built around a large peristyle courtyard, the lower one included the Hasmonean pool (20 x 12.5 m), a Roman-style bathhouse, and various servants’ quarters.

In the west wing the two large Hasmonean pools were combined into one large pool (32 x 18 m), surrounded by newly planted gardens. Another wing (perhaps a villa) was built on top of the artificial Hasmonean hill, but no evidence of this has been found.

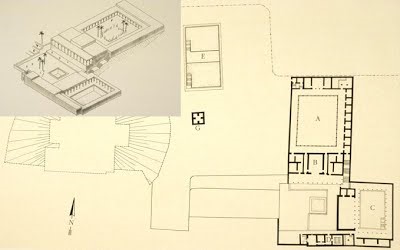

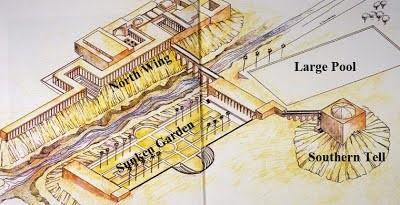

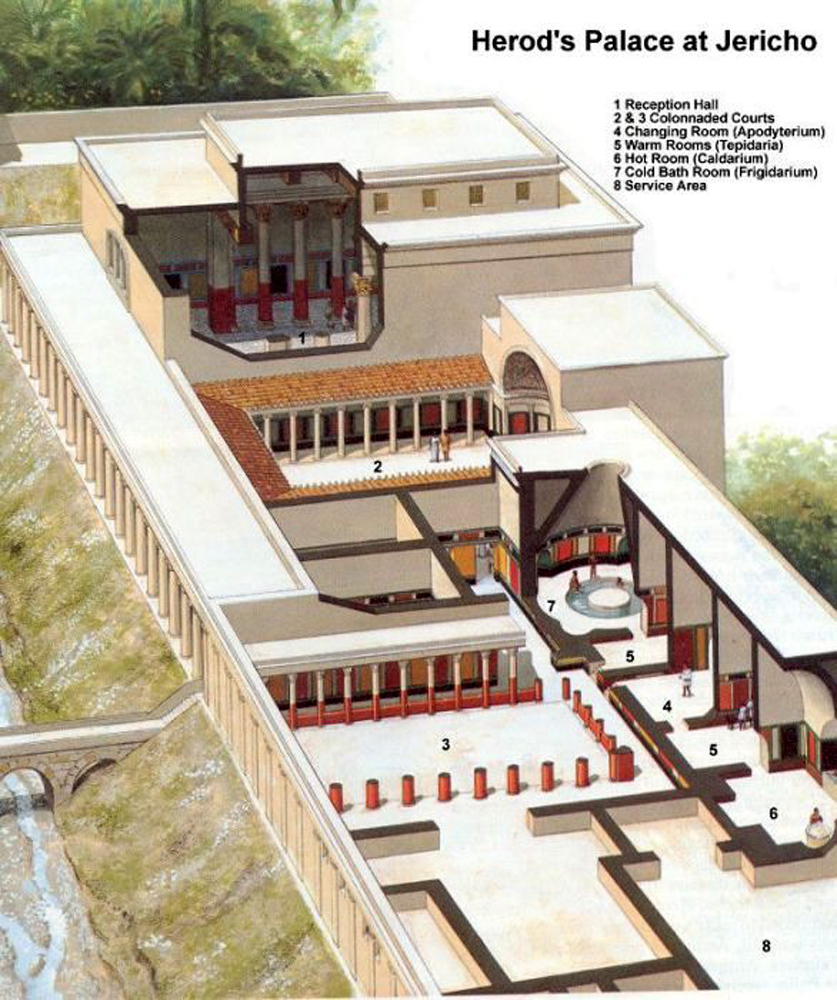

The largest and most sophisticated palace built by Herod at Jericho, the third palace, was constructed around 15 BC on both sides of Wadi Qelt, to the N of the first palace and to the SE of the second. It covered about 3 hectares, and was built along a grid system parallel to the wadi. Roman builders and craftsmen collaborated with local artisans using Roman concrete, which was covered by small stones in opus reticulatum and quadratum, together with mud bricks.

The main wing of the palace was the north wing. It included several palatial rooms, two small peristyle garden courtyards, a relatively large Roman-style bathhouse, and a huge triclinium. This triclinium (29 x 19 m) had rows of columns on three of its sides, similar in plan to that of the first palace. Most of its floor was covered by an elaborate opus sectile floor (its tiles were looted in antiquity). The walls, like virtually all those of this wing, were covered with frescoes. This unit also included two large colonnades, built along the rambla, facing the sunken garden. The walls of these colonnades, as well as those of other rooms, were decorated with stucco.

The other three large wings of the third palace were built south of the Wadi Qelt: the sunken garden, a huge pool, and a building.

The sunken garden, an elaborately shaped garden (140 x 40 m), was flanked by two raised colonnades at the short ends. The south facade was decorated with 48 niches, with a water channel in front of them. The centre of this facade was designed with a small semicircular garden, in the form of a theatre. The large pool (90 x 42 m) probably served for swimming, boating, and water games.

Only the foundations, a circle surrounded by a square, have survived of the building which once stood on the summit of the artificial hill. There is good reason to infer that above these foundations was a round reception hall, 16 m in diameter, with four semicircular niches around it (a similar hall, 8 m in diameter, was integrated into the Roman-style bathhouse of the N wing). After this reconstruction, this hall was similar in form to the contemporary one at the Temple of Merkuri at Baia. This raised hall was reached by a stair-bridge built on a series of arches. A second bridge, of which we have no evidence, was probably built across the Wadi Qelt, connecting the two parts of the palace.

The Winter Palace complex also included a number of structures built to the east of the Hasmonean palace. These structures (only partially excavated) were built along the fringe of the royal property, perhaps as housing for the administrative staff. On its eastern edge, a small “industrial zone” has been found, probably for processing some of the royal goods (perhaps the opobalsamum).

Another important building project of Herod was revealed and excavated by Netzer (1975/76) at Tell el Samarat, S of Tell el-Sultan. It consists of the remains of a complex unique in the Greco-Roman world, integrating a horse and chariot racing track, the cavea of a 70-metre-wide theatre, and a fine building (70 x 70 m) raised on the top of an artificial mound. Little has survived of the foundations of this building, which may have served as a reception area or a gymnasium.

This combined building project (equipped for horse racing, athletics, boxing, theatre and musical performances, such as those held at the quinquennial games in honour of Augustus, which Herod established and maintained in Jerusalem and Caesarea) is probably what Josephus is referring to when he mentions a hippodrome, a theatre and an amphitheatre in Jericho.

Very few other Hasmonean or Herodian ruins are known at Jericho. However, there are some independent dwellings.

Under Archelaus, the ethnarch built a small fortress-town near Arquelais, where his date growers took refuge. The area was heavily devoted to this crop on a wide strip of land.

Jericho as a whole functioned not only as an agricultural centre and a crossroads, but also as a winter resort for the Jerusalem aristocracy. However, since the work of Jesus and his apostles in Jericho was limited to the city and they avoided proximity to the former palaces of Herod, little or none of the available archaeological material has been of use for the writing of the novel “Jesus of Nazareth”[1].

¶ References

¶ Notes

This book is the novel “Jesus of Nazareth”, a biography about the Master based on The Urantia Book that is in preparation by the author. ↩︎