© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

Hebrew: Yerusalaym

Jerusalem is the Jewish city par excellence. All eyes and desires of every Jew, wherever he lived, were focused on his longed-for holy city. Jerusalem was located in the time of Jesus in what was the Roman province of Judea, which first belonged to a king subject to Rome and then came to be governed by a procurator. Jerusalem was situated rather to the south of the entire Jewish territory. Politically, the province of Judea and other Jewish provinces were subject to the authority of the governor of the province of Syria and depended on him.

¶ The climatology

In Jerusalem, which is 740 m above sea level, the average annual temperature is 16 degrees. The average in January is around 10 and in August around 27. It practically never falls below zero, but it is not uncommon for it to exceed 40 in summer. It never snows. But rainfall is not rare, and occurs in January and February, and sporadically in the rest of the months except in summer. However, the Jews were more concerned about the wind than about the heat or the cold. In spring the sherquijje, a kind of sirocco or warm wind from the east, was frequent, and also the khamsin, although more common in summer, or simoom from the desert, coming from the southeast. Both were particularly dangerous for people, animals and crops.

¶ The present city and the city at the time of Jesus

The present city of Jerusalem, despite being one of the most important religious tourist centres on the planet, bears little relation to the physiognomy of the ancient city. Centuries of wars and sieges have erased the traces of the past until they have disfigured the city that Jesus knew. Very few of the places that are offered to the visitor as the sites of the important events of the Master’s life offer any credibility, and their interest lies in the fact that it was in these places that a dubious tradition established the event. However, in this document we do not intend to enter into archaeological discussions about places venerated by believers, but only to offer a perspective of what scholarly research has been able to confirm. In a future study we will address the question of the veracity of these places.

¶ Overview

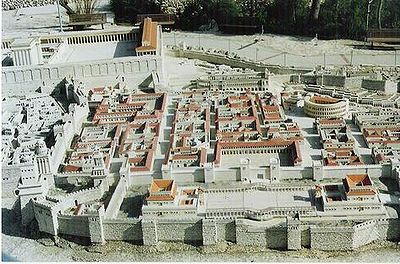

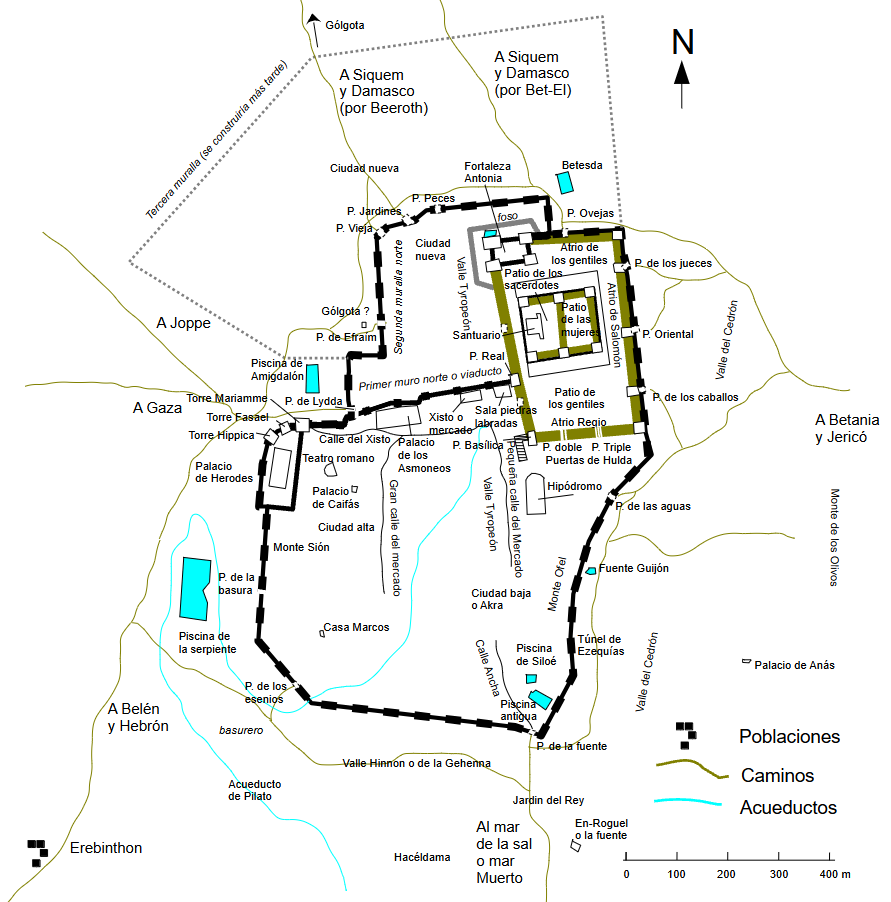

The Holy City was, like many important cities of the time, a walled city. The entire urban core appeared surrounded by a wall that gave it an elongated appearance from north to south. The northern part had two walls, one inside the other: the first north wall or viaduct, which started from the west side of the temple and reached the north façade of Herod’s palace and connected them both by the upper passage of the wall; and surrounding this, and covering a wide area to the north, the second north wall.

The buildings were usually one story with a non-habitable upper terrace or attic, or two stories, for the wealthier Jews. Among these dwellings, two buildings of spectacular size stood out imposingly: one was the great enclosure of the temple (religious and spiritual center) with the fortress Antonia, and the other the palace of Herod the Great (governmental center). The entire city was crossed, from north to south, by a depression or channel called the valley of Tyropeon (in Hebrew hagai). On both sides the population settled on several mounds. The eastern mounds were Mount Moriah, to the northeast, on which the temple and the fortress Antonia sat, and Mount Ophel, at the southeast end of the city, and which in ancient times was where the City of David or Jebus sat. The western mound was Mount Zion, on which Herod’s palace stood.

Surrounding the holy city were several torrents or channels. Between the eastern wall and the Mount of Olives (called Eleona in Greek and Olivete in Roman) was the so-called Kidron channel, which ran through the Valley of Jehoshaphat, and to the south and west, the Valley of Hinnon or Gehenna, on the southern slope of which was located the town’s garbage dump.

The buildings, limited by these narrow valleys, had to extend northwards, the only possible direction. In Jesus’ time, this part of the city was relatively new, and there were rich, new neighbourhoods and many orchards. At that time, the construction of a wall that would surround this area, the third northern wall, had not yet begun, and was built several decades later. To the north was another high mountain, Mount Scopus (named after the Greek word skopein = observation, watchman).

¶ The doors

To cross the walled enclosure there were a few gates or doors, which went through the wall. In the northern area there were four: the Sheep Gate, which went directly through the temple wall and communicated with the area of the Courtyard of the Gentiles, where cattle and products for sacrifices were sold and where the money-changers had their market; the Fish Gate, so called because pagan merchants (Phoenicians) who brought fish set up their stalls there; the Garden Gate, which led to the orchards located in the new city; and the Old Gate, very close to the previous one, and through which one accessed the new quarter of the city.

On the western side there were two entrances: the Gate of Ephraim, close to the famous rock of Golgotha, and the Gate of Lydda, located near an entrance through which one could cross the first northern wall or viaduct.

The southern area had three gates: the Garbage Gate, the Essenes Gate, and the Source Gate, the latter so called because it was located in the direction of En-Roguel, a place where there was a spring.

On the east side there were four gates: the Water Gate, the Horse Gate, the Eastern Gate, and the Judges Gate. The last three were rarely used to enter the city because they forced the traveler to climb the steep slopes formed by the dry bed of the Cedron.

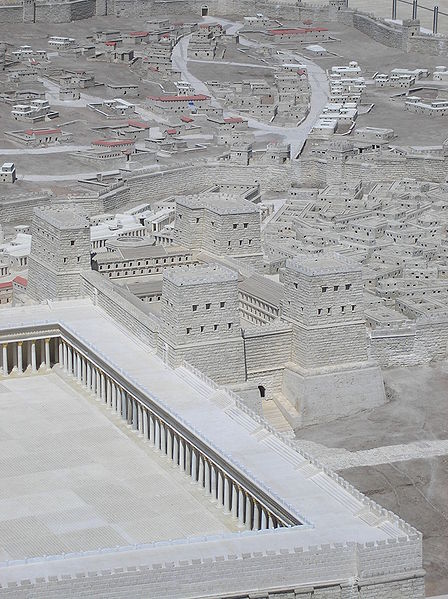

¶ The temple

The immense temple precinct was in the form of a rectangle, slightly longer on its north side than on its south side. It alone occupied more than a fifth of the city’s surface area. It was enclosed by robust walls some 50 m high. Its north side, known as the Courtyard of the Gentiles, since the westernmost end of which was attached to the Tower of Antonia, measured some 300 m long. Facing the Mount of Olives, the east façade, all of it in white marble (or according to other scholars, stone with stucco that gave the appearance of marble), forming what was called the Courtyard of Solomon, covered a distance of more than 400 m. The western wall was practically the same dimensions, while the south side was a little more than 250 m, and there was another covered space, the Royal Atrium, Royal Stoa or Basilica. This extremely spectacular portico had its own entrance from the west, which included a staircase and a bridge supported by a sturdy construction (today called Robinson’s arch, and at that time probably the arch of the Basilica). In this atrium the civil and non-religious affairs of the temple were settled. For this reason, it had its entrance directly through the arch.

The entire inner esplanade of the enclosure, which was not within the sacred space of the Sanctuary, formed the so-called Courtyard of the Gentiles, or Esplanade of the Gentiles. Only there were foreigners permitted to be present. The Sanctuary stood imposingly in the centre of the esplanade. To delimit this space, a low wall about a metre high, called soreg or jel, was being built around it in Jesus’ time, as it had not yet been completed. All pagans were forbidden to cross this fence under construction under penalty of death. One of the stone inscriptions has been found, which, in Greek letters chiselled and decorated in red, for added emphasis, warned pilgrims of this: “No foreigner shall pass this balustrade or enter this enclosure surrounding the temple. Anyone caught doing so shall be responsible for his own death, which shall be carried out immediately.” This low wall was being laid out with eleven access doors, four on the north side, three on the east side, and another four on the south side. The west side had no entrances and only had the rear façade of the immense sacred building.

The entrance to the temple was provided by gates in all the walls. In the south, the Huldah Gates, named after the biblical prophetess, are particularly famous. There were two of them: the Double Gate, with two openings, used for exit, and the Triple Gate, with three openings, used for entry. These gates, through passages under the Basilica that were decorated with geometric designs, with rosettes reminiscent of chrysanthemums, buttercups and other local flowers, and with drawings of vines and bunches of grapes, led directly to the Temple Esplanade via a flight of steps. These were the entrances that pilgrims and the common people used. Next to the entrance to the two Hulda Gates there were miqwaoth or public baths that pilgrims had to use to purify themselves.

In the west, we have already spoken of the Basilica arch gate, through which one entered directly into the Royal Atrium (and thus the religious and civil parts of the temple were separated by different entrances). This arch, which was the largest in the world at that time, to give us an idea of its enormity, weighed 1000 tons, and above it ran a bridge about 15 m wide (like a 4-lane highway). Also in the west wall there were three other entrances apart from the Basilica gate. The most important is the one that accessed the western atrium directly through the first northern wall or viaduct at its point of union with the temple, and that for lack of another name I would call the Royal Gate (Josephus simply calls it the “great gate”, and in fact it must have been the largest). This access was the one used by the Herodian royalty and the rich inhabitants of the upper city. Josephus tells us of an event, dated shortly before Herod’s death, which scholars believe refers to this gate. Apparently, Herod, in order to honour Rome, had a huge golden eagle hung over the jamb of this great gate, which provoked the indignation of the Pharisees. A couple of them lowered themselves down by ropes and destroyed the eagle, which cost them their execution. The Court of Solomon was also accessed by two other entrances, located a few metres above street level, and which were reached by steps attached to the walls of the wall. These two entrances, located on either side and equidistant from the royal gate, would ascend to the Court of the Gentiles by ramps like the Hulda Gates.

To the north, the only access was the Sheep Gate, through which cattle entered for sacrifices and for sale (remember that the sales stalls were to the north next to the Court of the Gentiles).

To the east, the gates in the eastern wall of the city allowed direct access to the Atrium of Solomon.

We must bear in mind that Herod, when building the temple, extended the temple’s extension beyond what Mount Moriah allowed. To do this, high retaining walls were built surrounding the enclosure. Then the interior was filled with earth, and to avoid high pressure against the walls, several floors of vaulted rooms were left, supported by columns and Roman arches 5 meters apart, paving the resulting upper surface, called the podium. The Atriums, the Esplanade of the Gentiles, and the temple itself were later placed on it. For this reason, the subsoil of the temple esplanade was full of enormous passages, with vaulted domes, large chambers, warehouses, pipes for pipes, water tanks for ablutions and so on. A whole underground world unknown to the common Jews of that time, and only visitable by the temple staff.

The most impressive feature of the Temple Mount is its vast surface area. Including the adjacent esplanades, it was the largest sacred complex in the ancient world. The question is what could have prompted Herod to undertake this great work. The answer is related to the nature of the temple activities. While other peoples worshipped their gods in a multitude of temples, the Jews served one God in one temple and flocked in large numbers for the three pilgrimage festivals: Sukkot (Tabernacles), Shavuot (Pentecost), and above all, Pesach (Passover). At these times, crowds of Jews from all over the country and from all over the world came up to Jerusalem. The vast esplanade was necessary to accommodate both visitors and the inhabitants of the city during the sacred ceremonies. Added to this is Herod’s love of great undertakings, which led him to initiate countless works of enormous proportions.

As we have said, the work was not finished at that time. (“It took forty-six years to build this temple, and you will raise it in three days?” the Jews said to Jesus around the year 30). Herod had begun the new construction in 19-20 BC, and it was not finally finished until 62-64 AD, during the time of Governor Albinus. However, by the time of Jesus, the most important part of the work had already been completed. Herod’s innovations were: raising the ancient sanctuary from 30 metres to 60 metres (a building of about 20 floors today!); building a large gate between the women’s court and that of the Israelites; enlarging the outer court to the north and south by means of gigantic foundations; building porticos around the temple esplanade. As soon as these works were finished, and before the Jewish insurrection of 66, new works were resumed. However, from the time it was considered completely finished until it was demolished and destroyed by Roman troops, only three to four years elapsed.

During the Jewish holidays, the Courtyard or Esplanade of the Gentiles was extremely busy. A good part of the northern area near the Courtyard of the Gentiles was packed with stalls, tables, vendors’ stands and cages with animals. This market was for the sale of the obligatory animals and products needed for religious rituals. Pigeons, lambs, goats and even oxen were sold there. In many of the stalls, which were nothing more than simple wooden boards mounted on the cages themselves or, at most, provided with legs or folding supports, the ritual products were offered and shouted to the public: oil, wine, salt, bitter herbs (mint, dill, cumin), nuts, roasted almonds and even jam. Also in the middle of that open-air market was a long row of tables of the so-called moneychangers (mostly Greeks and Phoenicians), who were dedicated to exchanging coins, especially the exchange of the Tyrian half shekel for the obligatory temple tribute.

The sacred precinct of the Sanctuary itself occupied a new, smaller rectangle within the courtyard, slightly shifted to the north and close to the Antonia fortress. Its dimensions were about 200 m by 140 m. It was surrounded by walls lower than those of the enclosure, with atriums and guarded at its corners by turrets. Dividing it into two halves was a fifth wall with an atrium and a wide gate with a semicircular entrance, the famous Nicanor Gate. One half was the so-called Courtyard of the Women, who could not attend the ritual services except from a distance, and the other the Courtyard of the Priests, intended for men and the temple staff. In the latter was located the Altar and the magnificent Sanctuary, of considerable height, about 60 m, and where the Jews believed that the presence of God was found. It was the sacred place par excellence, and no one, except the priests, could have access to it.

The temple, built by Herod the Great, had been erected with all the grandeur and luxury of the time. The construction of the walls had been carried out using courses of enormous stone ashlars, meticulously squared and fitted together. At a certain height from the street, a course of stones called the Master Course had been arranged in the walls, with stones that reached up to 12 metres long, 3 metres high and, it is estimated, 4.5 metres thick, weighing over five hundred tons. The courses above and below the Master Course did not generally have such large ashlars, with an average height of 1.2 metres. The aim of the Master Course was to give greater stability to the other courses. All the stones on the façade had the classic Herodian decoration in cushion, with a raised border on the edge that surely offered curious effects in the sunlight. The same effect must have been produced by the cup-shaped projections that were used to hoist the stones with cranes, and which were normally removed once the stones were placed, but which in many cases were left here. Another curious detail is that each row was shifted inwards by about 2.5 cm, about two fingers, creating a pyramid effect that prevented the walls from being seen from the street as if they were falling on top of each other.

The Court of the Gentiles had been enclosed by a superb colonnade. In the Royal Portico, as we have already said, there were as many as 162 slender Corinthian pillars, so wide that it required three men with outstretched arms to span them. All these porticos or atriums were covered with panelling made of cedar wood from Lebanon.

As you entered the sanctuary, no matter which way you came, gold was everywhere. You had to pass through gates covered with gold and silver. The only exception was the Nicanor Gate, which was made of Corinthian bronze, but which shone as if it were gold.

Once inside, in the women’s atrium there were golden candelabras, with four golden cups at their top, and the temple treasuries, where donations and taxes were collected, were filled with gold and silver objects.

The facade of the sanctuary, about 28 m2 (100 cubits square), was covered with gold plates, as were the wall and the door between the vestibule and the Holy Place. The vestibule of the sanctuary was entirely covered with gold plates the thickness of a denarius and 100 cubits square. On the roof were sharp spikes of gold to scare away birds. From the beams of the vestibule hung gold chains. There were two tables in the vestibule, one of marble and the other of solid gold. Above the entrance leading from the vestibule to the Holy Place was a vine, also of gold, which was constantly growing with donations of golden branches that the priests were responsible for hanging. In addition, above this entrance hung a gold mirror that reflected the rays of the rising sun through the main door (which had no leaves). It had been a donation from Queen Helena of Adiabene. There were also other offerings in this vestibule. The Emperor Augustus and his wife had once given bronze vases and other gifts, and his son-in-law Marcus Agrippa had also made gifts.

In the Holy, situated behind the vestibule, were found singular works of art: the massive seven-branched candelabrum weighing two talents (70 kg) and the massive table of the shewbread, also weighing several talents. The sancta-sanctorum must have been empty and its walls completely covered with gold.

The rabbinical treatises speak of ten degrees of holiness on earth, which were situated in concentric circles around the sancta-sanctorum: 1) the country of Israel; 2) the city of Jerusalem; 3) the temple mount; 4) the soreg or jel, a terrace with a balustrade that separated it from the rest of the temple esplanade, and which marked the limits permitted to the pagans; 5) the atrium of the women; 6) the atrium of the Israelites; 7) the atrium of the priests; 8) the space between the altar of burnt offerings and the temple building; 9) the temple building; 10) the sancta-sanctorum.

According to this division, what constitutes the so-called “inner court” includes the circles of sanctity 6 and 7: the court of the Israelites and that of the priests. The other three innermost circles, 8, 9 and 10, also belonged to the inner court, but were in no case accessible to lay people. On the contrary, the space located behind and on either side of the building did not belong to the space that was absolutely forbidden to them. The measurements of these circles, 6 to 10, have been indicated in the drawing included.

The width of the jel was 10 cubits (1 cubit = 525 mm). The inner court, however, was not directly connected to the terrace, but between them were side buildings where the gates were arranged to lead from the inner court to the jel. These gate buildings had an exedra or vestibule (30 cubits wide) with seats and a room above. However, between the jel and the inner court were not only the gate buildings, but there were other side buildings that connected these gate buildings. On the sides to the north and south of the inner court were the treasury chambers and six rooms were used for cultic purposes or similar. Between the women’s court and the jel there were also gate buildings and other buildings. In particular, four rooms 40 cubits square were located at the four corners of the women’s court. Here we had to add to these rooms those adjacent to the Nicanor Gate and the 15 steps that led to it from the women’s atrium.

¶ The Antonia fortress

Fortification attached to the north-western edge of the temple enclosure, built by Herod the Great when he rebuilt the old fortress of the Maccabees called Baris and renamed it Antonia in honour of Mark Antony, his benefactor. Scholars debate whether the procurator had his residence there during religious festivals, or whether he lived in Herod’s Palace, in the western part of the city. What is clear, from the testimonies that have come down to us, is that it is very likely that there was a Roman garrison in both constructions.

The appearance and layout of this building is a matter of pure speculation, as no trace of its ruins remains. It was completely demolished during the siege of the city in the Jewish war of the first century. Only the rock base on which it rested can be seen today on some rocky outcrops to the north of the esplanade of the present mosques. Therefore, the scheme I offer here must be taken with a grain of salt and is based on descriptions found in books by various specialists.

Surrounding the castle was a stone wall one and a half metres high, and after ten to fifteen metres of waste ground there was a deep ditch of about 22 m. This ditch, dry at that time, surrounded the residence of the Roman procurator all around, except for the south side, which was attached to the temple. The foundation of this bastion was a gigantic rock, completely smoothed at the top and sides. Herod, in anticipation of possible attacks, had covered the sides with enormous iron plates, so that access through them was impassable. And on this solid base was raised the fort, built with enormous rectangular stones.

The moat was crossed by a drawbridge about 5 m long, supported by thick logs on which a thick metal cover had been fixed. Close to the moat, and inside it, attached to the fort, was the so-called Strution pool, a pool that had been collecting rainwater since the time of the Hasmoneans, and which has now been located under an ancient pavement from the time of Hadrian. It is not known whether it was fed by sources other than rain, and which conduits emptied into it. But what is certain is that it was used as a water supply by the inhabitants of the fortress.

There is no complete consensus, but it is believed that the four corners of the castle were reinforced by as many towers, equally fortified. Three of them were 50 cubits (22 m) high and the fourth, which was attached to the temple, was 70 cubits (32 m). However, there are scholars, who after carefully reading Flavius Josephus, have come to the conclusion that there was only one large tower.

The grey stone façade, 40 cubits high (18 m), was crowned by a perfectly crenellated walkway, and was about 100 m long, with three rows of windows (those on the first floor were loopholes). At the bottom of the façade and in its centre, a long staircase with two curving side ramps led up to a kind of terrace or viewing point through which one could access the entrance tunnel, located about 5 metres high. This northern entrance is not sometimes drawn in the recreations I have found of the fortress, but it seems to me that it must have been an essential entrance to allow access for cavalry and the procurator. This staircase and the upper viewing point, moreover, would have been the perfect place where the public trial of Jesus could have taken place, although some specialists place this trial in a wide stepped courtyard inside Herod’s palace.

Entering through the vaulted tunnel that served as the entrance at the north end, one was connected to a quadrangular open-air courtyard measuring about 50 m on each side and paved with hard limestone slabs measuring 1 m2 each. A multitude of doors, crowned by wooden lintels forming semicircular arches, were lined up on the sides, under a number of porticos supported by colonnades. The bedrooms, stables and some warehouses led out onto this large courtyard. In the centre of it there was a column with rings and a small circular pond, which was used to hold and clean the horses.

A white marble staircase that started from a corner of the courtyard led to the upper floors. The ground floor of the fortress housed the troops, and the stables and warehouses were arranged. The second floor housed the residence and private quarters of the prefect, the tribune in charge of the garrison and the officers. The third and higher floors housed the arsenal, the administrative rooms and the part of the troops in charge of the surveillance from the battlements. In one of these rooms, an important Jewish treasure was also kept: the vestments of the high priest, which were only given to him on the occasion of the main festivals. This was one of the restrictions imposed by the Romans on the normal functioning of the temple that most affected and displeased the Jewish people.

In order to access the fortress, apart from the entrance passage under the north façade, there was a drawbridge attached to the west wall of the temple, which was accessed by an inclined passage at the base of the southwestern tower. There were also two large, solid gates, large enough for a man on horseback to pass through, located on the south façade, which faced the temple’s esplanade of the Gentiles. Through these two gates, located within the so-called Atrium of the Gentiles, the troops accessed the temple esplanade to carry out their surveillance and control tasks of the huge population of pilgrims who filled the holy precinct, especially during the festivities.

¶ Other constructions

In Jesus’ time, the great building king was Herod the Great (37-4 BC), and he left his mark on the Jewish geography, especially in Jerusalem, with his building zeal. Here is a list of the buildings he built during his reign:

- Restoration of the ancient temple until it was as we all know it. It was his crowning achievement. It was therefore called Herod’s temple. We have spoken extensively about it before.

- To the north of the temple, dominating it, the Antonia tower was built, located on the same site where the temple fortress called Bîrah or Barîs had previously been built. We have also spoken extensively about it before.

- Construction of Herod’s Palace, near the western wall, next to the western gate leading to Lydda.

- Construction, in the same place, of the three towers of Herod: Hippicus, Fasael (the tallest, 75 m, imitating the lighthouse of Alexandria, but half its size) and Mariamme.

- The magnificent tomb that Herod had built during his lifetime, but which was not used, since the king was buried in the Herodium.

- The theater built by Herod in Jerusalem.

- The hippodrome built by Herod in Jerusalem. It was located in the upper part of the city.

- Construction of an aqueduct (see route on map).

- Monument over the entrance to David’s tomb.

Regarding other constructions that were not the work of Herod:

- As for the gymnasium or palaistra, it was a place of exercise built during the time of Greek domination. It was not built by Herod. It is unlikely that it still existed in the time of Jesus.

- Nor was the Palace of the Hasmoneans or Maccabees, whose name clearly indicates the period to which it belongs, built by Herod. This building was situated at the western end, occupying the upper part of the city, west of the temple and above the Xisthos or Market. This was the palace occupied by Herod Antipas, Philip and the rest of the Herodian royal family during their visits to the city.

- The princes of Adiabene, a kingdom situated on the borders of the Roman and Parthian Empires (in present-day Iraq), after embracing Judaism and moving to Jerusalem, had other large buildings built around the time of Jesus’ crucifixion. Therefore, during Jesus’ lifetime, these palaces were probably still under construction. A palace of King Monobazus was supposedly being built, situated on the southern part of the eastern hill. Also a palace of Queen Helena of Adiabene. This palace would be situated in the centre of the Akra; also, consequently, on the eastern hill. As for the exact location of the palace of Princess Grapte of Adiabene, it is uncertain, although it is certain that it would have been not far from the temple, perhaps on the eastern hill as well. Queen Helena built herself, three stadia north of Jerusalem, a tomb in the form of a triple pyramid, where she was buried around 50 AD. It had spectacular columns and its magnificence equaled that of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus.

Among the great works of construction we must finally mention the aqueduct built by Pontius Pilate. To build it he took money from the temple and this work provoked a popular revolt, which had to be suppressed with the soldiers’ clubs. It followed the same route as the one built by Herod, but was shorter and safer. The materials used to build it were lead and mortar.

One last building: on Mount Ophel there was a synagogue with a hostel for strangers and a bathing facility.

¶ Artistic constructions

The above-mentioned buildings are mostly sumptuous buildings, and the artistic trades found ample scope for their work there. Herod’s palace in particular was rich in unique works of art. The most diverse craftsmen had competed in both the exterior and interior decoration, in the choice of materials and their use, and in the variety and luxury of detail. Sculptors, weavers, garden and fountain installers, silversmiths and goldsmiths were involved.

The main works of art are the tombs called tombs of the kings and the three funerary monuments of the Kidron Valley, today known as the tombs of Absalom, James and Zechariah (or monuments of the prophets).

The tombs of the kings are the pantheon of Helen of Adiabene, opposite the tomb of Helen, in the three pyramids that her mother had built three stadia from the city. Today, a cornice with garlands of fruit and foliage in the form of scrolls is in fairly good condition. In front of the entrance leading to the burial chamber lie the remains of columns, between which are Corinthian capitals. This structure probably did not exist during Jesus’ lifetime, as Queen Helen moved to Jerusalem around 30 AD and died in 50 AD. In the tomb of Absalom, Doric and Ionic capitals, half-columns and pilasters are preserved. And immediately above the capitals is a decorated frieze; the architrave is Doric. In the tomb of James there are columns with Doric capitals, and above them a Doric frieze with triglyphs. In the tomb of Zechariah, four Ionic capitals can be seen.

¶ Current constructions

The underground of Jerusalem was almost hollow. The royal caverns served as quarries for a long time. These famous caverns or caves, such as the so-called “cotton cave”, still exist today. These caves extended for hundreds of meters. A particularly large and deserted cave was the Zedekiah Cave. It was about twelve miles long (probably Egyptian miles), i.e. about 19 km. There was a cavern under the temple hill and the atriums. Underground passages in the city were also a very common construction and were very much used in times of war; many inhabitants hid there.

Fountains, wells and other cave excavations were also very common, as well as ovens and places for smoke to escape.

There were several canals in the city. In such an arid place in summer, water always needed cisterns to store it and wells. There was a canal that ran from the outer court to the Kidron Valley.

To the south, between the Hippicus Tower and the Essenian Gate, there was a place called Besou or Bethso, “place of garbage.” This was the place where garbage was thrown away. Near the Hinnon Valley there was also the so-called Garbage Gate. This is because the Hinnon Valley had been discredited since ancient times, as it was associated with the ancient cult of Moloch. This valley passes through a place called Gehenna, from which it took the meaning of a cursed place, or hell, which was later given to it.

There were also drains in Jerusalem, and some of these installations were fully up to modern standards. They were 1.78 to 2.36 m high inside, and 0.76 to 0.91 m wide. They seem to have been provided with holes to receive water from the street, as well as with manholes for cleaning.

¶ The city

At that time, Jerusalem was divided into two large centres, separated by the Tyropeon depression or valley: the upper area or sûq-ha-elyon, located to the west, and the lower area or sûq-ha-takhton or akra. The fundamental characteristic of both areas, and hence their name (sûq = bazaar), is that both were home to the bazaars or stalls of the different groups of artisans. Each of the sectors of the city was crossed by two main streets, adorned with colonnades: the large market street, in the upper area (the current sûq Bâb el-'Amud or Bazaar of the Damascus Gate); and the small market street, in the lower or old city, which more or less followed the bottom of the Tyropeon valley (current el-Wâd street). The second northern wall enclosed the northern part of the Akra quarter to the north, beyond the south-eastern hill, the Ophel. Due to the extension of the temple, the Tyropeon valley formed the only link between the northern and southern quarters of the Akra.

These two commercial arteries were linked by a swarm of cross streets that formed a veritable labyrinth. In this network of alleys, most of them unpaved and soaked in a stinking smell, a mixture of burnt oil, stews and urine thrown into the middle of the road, thousands of houses were crammed together, almost all of them single-storeyed and with peeling walls. All the streets came from the east and the west and crossed the Tyropeon valley. The most important of these cross streets was the street that ran from Herod’s palace to the temple, reaching it at the bridge of Xistho (the current tarîq Bâb es-Silsileh, one of the main commercial bazaars today). This street ran parallel under the shadow of the enormous viaduct that formed the first northern wall, and ran from the Lydda Gate to a western entrance in the centre of the western façade of the temple.

The two main streets eventually led to another, much wider street, or Pool Street, because it led to the famous Pool of Siloam or Pool of the Envoy, at the southern end of the city, next to the great Old Pool and the Fountain Gate. These pools were fed by a fountain, the Gihon Fountain, which, from a spring next to the wall, crossed the wall through the so-called Hezekiah Tunnel.

The swarm of artisans and merchants from both areas had caused a clear rivalry between the two sectors in the city, reaching unsuspected extremes. It turns out that while in the lower or old city the most noble and respected professions had settled, in the upper city the pagan artisans, the proselytes, and above all, the community of fullers or fabric bleachers, who because of their unpleasant profession, had been despised, dominated.

These are the professions and places that we have listed below:

- In the new city: the wool-carders’ alley was the site of the bazaar or market for wool sellers (sûq sel sammarîm); to the north there must have been fullers in the new city, since in the north-east corner of the northernmost wall there was a monument to the fuller, and also a clothing market; in the northern suburb there would be the cutters’ workshop; finally, outside the city walls, to the north, there would be the blacksmiths’ bazaar.

- In the upper city we have to the north the most important neighborhood of the fullers (all of them pagans) and the artisans of artistic objects.

- Finally, in the lower city, near the Garbage Gate, the weavers’ quarter.

As we can see, most of the despised trades were located in remote places. The weavers were near the Garbage Gate, which was a despised area. The tailors, moreover, were usually located near the city gates, because their profession was not very well regarded. Because the pagan fullers were located in the upper city, the spit in the street of one of these fullers was considered impure, which means that people concerned about their ritual purity never frequented this area of the city. The merchants of Tyre (pagans) who brought fish to the city were located at the Fish Gate. This area, the northern part of the new city, was a frequent place for pagan artisans and merchants and was an area rarely frequented by ritualistic Jews. The tanners, according to a law, had to establish their workshops outside the city (and any city) at a minimum distance of 50 cubits.

Other guilds whose location is unknown are: the bakers’ bazaar (it is worth noting that a bakers’ bazaar was strange, since in those days bread was usually made at home, and it was probably related to the bread sacrifices in the temple); the butchers’ street; a market for fattened birds; and others.

In the passageways such as the gates and near the walls there was also another group of people who were very numerous in those days in the cities: the beggars. There were different groups with similar ailments (the lame, the crippled, lepers, the blind…).

The area around Jerusalem was rich in olive groves. Olive trees were the most important trees and plants in and around the city. The soil was very suitable for growing olive trees. In fact, olive groves were much more widespread in Jesus’ time than they are today. Various names for the city are composed of “oil”, “olives” and “olive trees”. To the east of the city is the Mount of Olives (also called the Mount of Olives, Mountain of Olives, or Olivete; in Hebrew tûr zêta). Here the plantations were of particular importance and number. It is also known that there were olive groves south of the city, in the Hinnom Valley. There were numerous wine presses on the outskirts of the city, all around. (It is particularly curious that Jesus stayed several times when he was in Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives, in a farm called Gethsemane, a Hebrew word meaning “oil press.” It is understandable why he did so; farms of this type were very abundant in the city, and in addition, the Mount of Olives was a very popular place for Galileans during their festive pilgrimages.)

To the north there were many orchards, with their fences and enclosures. The whole northern part had long been full of gardens (or more precisely orchards). For this reason there was a gate in the city called Gennath, the Garden Gate, which was situated in the first northern wall.

Barely two kilometres east of the city was the village of Bethany. Between Jerusalem and Bethany there were many trees. Bethphage, the village next to Bethany, has a name which means “house of green figs”, indicating the importance of fig plantations in that area. To the south-east, the lower course of the Kidron Valley was particularly suitable for orchards. To be sure, the Kidron Valley was a wadi which only had water in winter, as it is still today. However, it received a special irrigation system. A canal supplied the blood of the victims sacrificed in the temple and led it to these orchards, serving also as an excellent fertilizer.

On the western hill of the Kidron Valley, south of the temple esplanade, vines were undoubtedly cultivated. Further south, below the pool of Siloam, the orchards of the Kidron Valley received their water from the spring of Siloam (in fact, the spring arose further north, at the spring of Gihon). At the confluence of the Kidron and Hinnom valleys, there were, from very ancient times, the royal gardens, in which a spring arose: En-Rogel. In these gardens were the royal winepresses.

To the southwest of the city, a village called Erebinthon oikos alludes to the cultivation of chickpeas.

¶ Economic, political and religious importance of the city

¶ a) Economic importance

Part of the Jewish territory was flat, in the region of Samaria and on the border with Idumea, while the other part, in the centre, was hilly. Therefore, the land had to be cultivated with constant care so that the inhabitants of the mountains could also obtain abundant crops. The city of Jerusalem therefore needed to import food. The city not only had to feed its population, but also the multitudes of pilgrims who flooded the city three times a year during the festivals. Compared with these needs, the first fruits were of little importance in the balance of Jerusalem’s supplies. Moreover, it is not clear to what extent they were given away, except that they were the property of the priests, and as for other tributes in kind, they could be paid in the place where one lived.

The situation was further aggravated by this circumstance: the surrounding area was notoriously unsuitable for the cultivation of wheat, and there were no cattle. The city could normally satisfy its food needs in Palestine. Only in times of scarcity, or after wars, did it depend on trade with distant countries.

Because of its location, the city was not only in need of essential products, but also lacked vital resources: raw materials and, above all, metals. It therefore had to import raw materials as well, partly from Palestine and partly from distant countries.

Among the agricultural products (wheat, oil and wine) of the province of Syria, including Palestine, only wine seems to have been exported in large quantities. Regarding Jerusalem in particular, the export of wheat was not to be thought of. Nor was there a product manufactured in Jerusalem that was characteristic of the city’s craftsmanship. However, oil was at the forefront of the products of Judea or the surrounding area. Moreover, the demand for oil in northern Syria was sometimes so great that its price was very high there. In Gischala, in northern Galilee, 20 sextarii of oil cost no more than 1 drachma; in contrast, in Caesarea Philippi, situated at the foot of the Hermon, some 30 km away, the price of 2 sextarii was 1 drachma, i.e. ten times more. We must therefore conclude that Jerusalem was an exporter of oil and an importer of practically all other basic products.

¶ b) Political importance

Jerusalem was the centre of Jewish political life. The great attraction it exerted on foreigners is explained by these three facts: it was the ancient capital, the seat of the supreme assembly and the goal of festive pilgrimages.

Jerusalem was the ancient capital. Herod’s court was a great attraction for foreigners. The Hellenistic spirit reigned in full force, with fights between wild beasts, gymnastic games, spectacles, chariot races in the hippodrome and theatrical performances. Foreigners who participated actively or passively in sports competitions, writers and other Hellenistic figures were guests of Herod’s court. In addition, Herod maintained numerous official relations; as a result of these, foreign envoys, messengers and guards came to Jerusalem.

Jerusalem was also the seat of the supreme assembly. The Sanhedrin, which by its origin and nature was the highest authority in the country and whose jurisdiction extended to all Jews in the world, held its sessions there. This was at least theoretically the case; its prestige as the supreme authority guaranteed it the ear of all Jews, although it could hardly use coercive means outside Judea. Since Judea became a Roman province in 6 AD, the Sanhedrin was its first political representation. A commission of the Sanhedrin constituted the financial assembly of the eleven Jewish toparchies, districts into which the Romans had divided the country. At that time, the Sanhedrin was also the first authority of the province in municipal affairs. Finally, it constituted the supreme Jewish judicial authority for the province of Judea.

The Sanhedrin, because of its importance, maintained relations with Jews throughout the world through its synagogues and, within Judea, linked Jerusalem administratively with the smallest of villages.

The three pilgrimage festivals were celebrated in the temple. The number of caravans attending them, due to the political importance of the festive gatherings, increased enormously in the years of unrest.

From 6 AD Jerusalem was only a provincial Roman town with a garrison, but this had little effect on the movement of foreigners. At the time of the Passover, and even with some regularity, the Roman procurator of Caesarea came to Jerusalem with a strong escort of soldiers to administer justice.

Thus, given the importance of Jerusalem as the centre of Jewish political life, many people came to it for both public and private business. And the political importance of the city also directly and indirectly influenced trade.

The kings had great needs due to their lavish lifestyle. In addition to the materials used in sumptuous buildings, which were to be provided by distant trade, they had to add the products of foreign civilization.

Indirectly, the political centre had always been a magnet for national wealth. In Jerusalem there were tenants of the customs house, not only those who rented the customs house in the Jerusalem market, but also those who hired various more extensive customs houses. Bankers and large merchants also settled in the city. Many of them retired to Jerusalem to spend their capital there and also to die in a holy place.

This capital had a double influence on trade. On the one hand, it attracted capital to Jerusalem by favouring commercial transactions. On the other hand, it created sales opportunities: rich people could afford great luxuries in clothing, ornaments, etc., and it was above all trade with distant countries that had to satisfy these needs.

¶ c) Religious importance

The temple consumed a huge amount of materials during the approximately eighty-two years that its construction lasted. The dignity of the sacred house demanded the greatest sumptuousness and the best quality in the materials used, such as black, yellow and white marble, as well as cedar wood. It is therefore understandable that in the description of Jerusalem’s trade with distant countries the temple represents the most important of the transactions.

The temple service also required the best quality of wood, wine, oil, wheat and incense. The cloth for the high priest’s vestments on the Day of Atonement was even brought from India. And the twelve jewels on his breastplate were to be the most precious stones in the world. But above all, the service required an enormous number of victims: bulls, calves, sheep, goats and doves. Every day certain victims were offered as public sacrifices for the community. During the Passover festival two bulls, a ram and seven lambs were offered daily as a burnt offering, and a goat as an expiatory sacrifice. Private sacrifices were also offered daily. These were to be offered to atone for the innumerable and precisely determined transgressions that led to defilement, and with these sacrifices legal purity was restored. On special occasions veritable hecatombs (i.e. hundreds of animals for sacrifice) were offered. During the festivals, the number of sacrificial victims was counted in the thousands. In this regard, we can appreciate the magnitude of these sacrifices if we consider that all the cattle found in the vicinity of Jerusalem, within a radius equivalent to the distance to Migdal-Eder, were considered as intended for sacrifice.

But most importantly, the Temple attracted huge crowds of pilgrims to Jerusalem three times a year. Especially at Passover, Jews from all over the world flocked to it. These masses had to be fed. Of course, they were supplied in part by the second tithe, that is, by the tithe of all the produce of the land and perhaps also of livestock, which was to be consumed in Jerusalem. But transporting produce in kind was only possible for those who lived in the immediate vicinity of Jerusalem. Those who lived further away were forced to exchange the produce for money in order to spend it later, as prescribed, in Jerusalem.

Thus, it was the temple above all that gave importance to Jerusalem’s trade. Through the temple treasury, to which every Jew had to pay his dues annually, Jews from all over the world contributed to Jerusalem’s trade.

Finally, the religious predominance of the city was absolutely decisive in its attraction to foreigners. Jerusalem was, above all, one of the most important centres for the religious education of the Jews. It attracted intellectuals from Babylon and Egypt and the worldwide reputation of its scholars was a lure for all kinds of students.

Jerusalem was important for the most diverse religious currents. The central nucleus of the Pharisees was there; we also find the Essenes there. Religious expectations were linked to Jerusalem. That is why all the messianic movements, very numerous at that time, had their eyes set on Jerusalem. Many settled in the city to die in that sacred place and be buried there, where the resurrection and the final judgment would take place.

But above all, the Temple was in Jerusalem. Jerusalem was the home of Jewish worship. Jerusalem was considered the place of God’s presence on earth. People went there to pray, because it was believed that prayer reached God’s ears more directly there. The Nazirite offered sacrifices there after fulfilling his vow, and the non-Jew who wanted to be a full proselyte. The sotah, the woman suspected of adultery, was brought there for God’s judgment. The first fruits were brought to the Temple. Mothers were purified there after every birth by means of the prescribed sacrifice. The Jews from all over the world sent their taxes to the Temple. The various sections of priests, Levites or Israelites went there when it was their turn. The Jews of the whole world flocked to the Temple three times a year.

It is difficult to get an idea of the number of pilgrims who gathered for the three annual festivals, especially for Easter. An approximate figure is 125,000 pilgrims for the Easter festival and about 50,000 inhabitants of the city. In other words, the number of pilgrims was several times greater than the size of the local population.

¶ The city’s situation for trade

Due to the extensive military protection and the colonizing policy of the Roman Empire, the area influenced by Syria extended further east than it does today. A flourishing culture was developing in Transjordan. The province of Syria, on which Judea was then practically dependent, was, together with Egypt, the leading province in trade among the provinces of the Roman Empire. Due to these circumstances, the situation for trade in Jerusalem was favorable.

Jerusalem was situated in the centre of all Judea. Moreover, for the Jews of that time, Jerusalem was the centre of the inhabited world, the central point of the whole earth, and for this reason the city was called the “navel of the world”.

In addition to its location, the city also enjoyed easy maritime communications through the ports of Ascalon, Jaffa, Gaza and Ptolemais, and was also approximately equally distant from all these ports and occupied a central position with respect to them.

However, Jerusalem did not enjoy comfortable trade relations. Despite its central location in a province with prosperous trade and favourable maritime communications, it was nothing more than a remote mountain town.

In the mountains of Judea there have always been numerous caves and hiding places which have been fertile ground for the activity of robbers. In fact, in the time of Jesus there were constant stories of bandits operating on the roads leading to Jerusalem. The road from Jericho to the holy city, very frequented and dangerous, was called “the road of blood.” (It is precisely on this road that Jesus places the parable of the Good Samaritan.) Looting was common in the area, although there was a special court that judged cases of theft and, at the same time, took police measures against it.

But Jerusalem’s lack of communications was even more serious than the danger of robbery by bandits. The high mountains surrounding the city made it more of a fortress than a commercial hub.

There is no east-west crossing of the watershed in Jerusalem; the nearest is far to the north. Communication between Jerusalem and the west, and especially with the east, is difficult and inconvenient. For this reason, Jerusalem could not have been a crossing point for the products of the rich Transjordan, which was flourishing at that time, nor a trading centre for the nomadic tribes of the desert. The crossing of the Jordan was therefore entirely ruled out, as was the crossing not far from the mouth of the Jabbok, which connects with Samaria (Sebaste) via the Wadi Far’ah. Transjordan’s main sea trade crossed the Jordan either south of Lake Tiberias, by the route between Gadara and Tiberias, or about 20 km further south, by the route between Gadara and Scythopolis, or it could also cross the Jordan by the pass 12 km north of Lake Gennesaret, by the Djisr Benât Yaqub bridge, the via maris, the ancient caravan route linking Damascus with the plain of Esdraelon.

Only one natural route ran through the environs of Jerusalem: the north-south route along the watershed from Nablus (Neapolis, Shechem) to Hebron. However, this route is one of the least important for Palestinian trade. It is only important for internal trade. All trade with distant countries had to aim at reaching the sea, so this north-south route was only of value in the case of a crossing with an east-west communication. But this was precisely where nature had not favoured Jerusalem.

However, despite this unfavorable geographical location for trade, it had considerable importance in the business of the area.

¶ The trading system

The level of commercial development in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus is, broadly speaking, that of an urban economy, or an economy of a period in which goods pass directly from the manufacturer to the consumer.

The profession of merchant was highly esteemed. There were even priests who were engaged in trade. And the family of the high priest had very lucrative businesses.

Goods were transported to Jerusalem from afar by camel caravans, often very large. Donkeys were also used as beasts of burden for trade with neighbouring regions. Because of the generally poor condition of the roads, carts were only used for short distances; Herod had 1,000 built to transport the stones for the construction of the temple. Produce from the immediate surroundings was brought to the city by the peasants themselves.

The safety of the roads was a vital problem for trade. Herod had taken vigorous action against the banditry that was then prevalent. He tried to ensure peace in the interior of the territory and to keep the bordering tribes of the desert within its borders. In the following decades, the Roman government also took care to protect trade. A line of protection against the desert peoples had already existed in early times. Under the domination of Trajan, the Romans again undertook to protect the borders by raising the limes.

Once in Jerusalem, the merchant had to pay the duties of the tax collector who had leased the customs office of the city market. Indeed, the tax collectors, as indicated in the Gospels, were mostly Jews. The collection of duties was inexorable.

Once the customs duties had been paid, the goods were sold in the bazaar corresponding to the merchandise in question. There were various markets: for grain, for fruit and vegetables, for cattle, for wood, etc. There was a market for fattened cattle and there was even a special place for the public display and sale of slaves; slaves were displayed and sold there. The final sellers attracted their customers by weighing the merchandise and encouraged them to buy by shouting their propaganda. At the time of purchase, great attention had to be paid to the weight, because Jerusalem had its own system. In Jerusalem, the measure was mainly counted by qab, and not, as in other places, by tenths. In addition, this measure of the qab clearly had a special value. The upper measure of capacity, the seah, was a fifth larger in Jerusalem than the “desert” one, and, in contrast, it was a sixth smaller than the seah of Sepphoris. To settle accounts, merchants and pilgrims could exchange their money at money-changers’ stalls.

Of course, Jerusalem also had its own coins: the Jerusalem ma’ah and the sela’.

In addition to the general regulations on keeping the Sabbath holy and on trading with pagans, special regulations were in force in Jerusalem for commercial transactions. In particular, the importation of unclean cattle, meat and hides was strictly monitored. Prices in Jerusalem were particularly high, and land near Jerusalem was particularly expensive.

The temple police were responsible for ensuring order in trade. There were market wardens, appraisers and market guards. Judges issued rulings on commercial matters and the priests had broad jurisdiction to change the value or price of the temple’s sacrificial products.

In addition to the traditional producer who delivered his goods directly to the vendors in the bazaars, there were also itinerant traders in Jerusalem who sold spices (they were called taggerê jarak, or roasted grain merchants). There were also large merchants; these were understood to be businessmen who had employees in their service and who travelled. It was these, in particular, who made use of the “accounting room” in Jerusalem. Evidently, monetary transactions were also carried out there on a large scale. It was said that after large transactions, when the accounts were settled, one might have lost all one’s fortune there. For this reason, the merchants of Jerusalem paid great attention to the time of the accounts; they did not sign beforehand without knowing who the co- signers were.

¶ Foreign trade

At the time of Jesus, abundant trade flourished everywhere, and Jerusalem, as the Jewish capital, was not exempt from this flourishing.

- Greece. The influence of Greece on the trade of Palestine, either directly or through Hellenistic culture in general, was extraordinarily great. This is indicated by the large number of words of Greek origin that were used, and which referred to all sectors of daily life, but mainly to trade. Latin words are also found, although in smaller numbers. There were merchants from Athens in Jerusalem and they had long and intense commercial relations. The most valuable door of the temple was made of Corinthian bronze.

- Lebanon. The much sought-after wood used to build the temple came from this country. The wood of this tree was visible everywhere in the holy building, especially in the coffered ceilings.

- Sidon. Sidon’s main industry was glassmaking. Many cups and plates came from this Phoenician city, including the utensils used in the temple.

- Tyre. We have already mentioned the fish stalls which the Tyrian merchants had in Jerusalem, in the northern part of the city. Tyre, like the other Phoenician city, was popular for glassworks and for the production of purple dye. Jerusalem’s coinage is often valued according to the value of Tyre’s coinage, and it is often said that the two were worth the same. Slaves of both sexes came mainly from Syria via Tyre; sometimes they came from further afield, passing as transit merchandise through the large slave market in Tyre. The importation of slaves played an important role: there was a place in Jerusalem where slaves were exposed for public sale.

- Cyprus. A very fruitful trade was maintained, especially in dried fruits, such as figs, highly appreciated in the holy city.

- Babylon. The Mesopotamian city supplied precious fabrics: hyacinth, scarlet, silk and purple. These fabrics were used, for example, to make the veil of the Holy One and the tiara of the high priest. The vestments of the priest in office were made of silk, and this material was also used in the liturgy of the Day of Atonement, where a silk cloth was spread between the high priest and the people. In addition, in the temple there was a wide supply of these fabrics for the curtains. Spices were also imported from Mesopotamia.

- Persia. Trade relations were also maintained with this country.

- India. There was a fruitful business with this country, especially in the area of clothing. As an example of this trade, on the evening of the Day of Atonement the high priest dressed himself in Indian fabrics.

- Arabia. Relations with this southern country were very intense. The Arabs supplied the country with a large quantity of aromas (probably raw materials for the manufacture of perfumes in Jerusalem), precious stones and gold. Arabian incense was very famous. The perfumes burned in the temple came from Arabic substances. Among the perfumes used in the temple we have cinnamon and cane fistula. They also had an important copper and iron business. Herod organised fights between wild beasts in Jerusalem and for this it was necessary to bring lions and other wild beasts from the Arabian desert.

- Egypt. It was an immense granary for the other countries where there were sometimes shortages of cereals, as was often the case in Jerusalem. From the eastern part of the Nile Delta came the flax of Pelusa, with which the high priest was dressed on the morning of the Day of Atonement. The manufacture of ropes came from Egypt.

In conclusion, trade with distant countries was of great importance to Jerusalem. The needs of the temple were fundamentally what determined imports to the holy city.

¶ Trade with neighbouring regions

In the past, as now, trade with the surrounding regions was essential to ensure the supply of the great city. The main supplies imported into Jerusalem were wheat, oil, livestock and wood. Judea supplied oil and olives, the rest of Palestine, wheat. Livestock was brought in from Transjordan.

¶ a) Wheat and flour

The importance of this grain made the city’s inhabitants dependent on it for their livelihood. In times of hardship, this product was scarce, and it made up the bulk of food imports. The countryside of Jerusalem was planted with plenty of olive trees, grain and legumes. However, the surroundings of the city were not very suitable for growing grain, so the surroundings of the city only covered a small proportion of the wheat needs and it had to be imported. Most of the wheat came from Transjordan. Hauran was the granary of Palestine and Syria. For this reason Herod had taken care to maintain the security of Transjordan, and thanks to his measures this region began to prosper. Samaria and Galilee also produced wheat. Wheat, wine, oil and meat were brought from Samaria. The wheat from Galilee was considered to be of the highest quality in Jerusalem and therefore usable in the temple. However, because it was transported through pagan territory, it could not be used in the temple and was only used for the city’s population.

As regards the wheat trade in Jerusalem, there was a wheat market in the city, with considerable transactions, and the sale of flour began immediately after the offering of the sheaf of presentation on the 16th of Nisan. Normally, the wheat was brought from distant regions. Produce from the immediate surroundings was brought to market personally by the small merchant; but transport from long distances was a matter for caravans. The large merchants, not always honest, found in this trade a particularly suitable field of activity for their business. The wheat trade in Jerusalem, despite its importance, was not carried on in the light of day, but rather behind the scenes.

As for the flour for the temple, it had to be of the highest quality. It was brought from Michmash (northeast of Jerusalem), Zanoah (southwest) and Hafarain (west of the plain of Esdraelon), the first two in the province of Judea and the third in Galilee, which denotes the scrupulousness that was followed when acquiring this flour. It could not come from Samaria or Perea.

¶ b) Fruits and vegetables

In Jesus’ time, the area around Jerusalem was a rich forest. There were numerous olive groves, as well as grapevines. There were also date palms and fig trees. Thus, there were sufficient fruit and vegetable plantations in the area around Jerusalem, and these plantations supplied vegetables, olives, grapes, figs and chickpeas. In addition to these products from the surrounding area, olives (oil) and grapes (wine) were brought from outside, especially from Judea. Wine was used for libations in the Temple, and some of this wine was brought from Judea and from the other Jewish regions, but especially from Judea (such as from the towns of Qeruhaim or Quruthim, north of Jericho, Attulaim, north of Gilgal, Beth Rima and Beth Laban, in the mountains, and Kefar Shegana, in the plain).

Among the fruits produced by Judea, the most important was undoubtedly the olive. The oil used as an offering in the temple was brought from outside from Tekoa in Judea and from Ragab in Perea.

At the fruit and vegetable market in Jerusalem we find figs and sycamore fruits. At Passover, the market provided a multitude of foods prescribed for the rituals: lettuce, chicory, watercress, thistles, and bitter herbs. Also sold were condiments (dill, cumin, mint, and others) and crushed nuts (from which the ritual jam or haroset was made).

¶ c) Livestock

There were large imports of livestock to Jerusalem. They were the basis of the temple sacrifices and the protein diet of the Jews. The rams came from Moab, the lambs from Hebron, the calves from Sharon and the doves from the Royal Mountain or the mountains of Judea. Animals also came from Arabia and Transjordan. In conclusion: the mountains of Judea supplied lambs, goats and doves; Transjordan, beef cattle, especially rams; and the coastal plain of Sharon, bulls.

Jerusalem had several animal markets, markets for profane animals (Jews were not allowed to eat meat from: pig, horse, mule, donkey, panther, fox and hare) and markets for cattle for sacrifices.

- First there was a market where live cattle were sold.

- There was also a market for fattened cattle, probably a meat market. Chickens were also sold there.

- In addition to the markets for unholy beasts, there were also markets for sacrificial animals. On the Mount of Olives there were two cedar trees. Under one of them were four stalls where the necessary items for purification sacrifices were sold: doves, lambs, rams, oil and flour. Under the other, 40 seah of pigeons for sacrifice were sold monthly. In Migdal Sabbaaya (Migdal of the dyers), a town near Jerusalem, there were 300 stalls for sacrificial animals and 80 stalls for fine woollen fabrics. In the temple itself there was an important trade in these animals, as well as that of the money-changers of the temple for making the obligatory payment. This flourishing temple trade was supported by the family of Annas.

¶ d) Other goods (stone, wood, wool, pottery, and slaves)

- Stone was used primarily in the construction of the houses, which could be supplied from the surrounding areas of the city. The stones for the altar and for the steps leading to it were brought from Beth-Kerem.

- Wood was also used, especially beams for the construction of the roof. At that time, when the surroundings of the city were much more heavily wooded than today, most of the wood for construction had been supplied from the surrounding areas. The surroundings of the city provided a supply of firewood. The willow branches for the Feast of Tabernacles were brought from Mosa, west of Jerusalem. Wood was also used extensively in the Temple: for construction, the wood of the cedar of Lebanon; acacia wood for the sacred utensils; and for firewood for the daily sacrifices, the wood of fig trees, walnut trees, and resinous trees such as pine, since the wood of olive and vine trees was not suitable for this use. There were also cedars, laurels, and cypresses in the surrounding areas.

- People from the countryside went to Jerusalem to sell wool, and sometimes they came from far away.

- Pottery was also traded in Jerusalem. But if it came from a town further away than Modit (about 27 km), then it was considered impure.

- Slaves of both sexes were part of the merchandise. In Jerusalem there was a place for their sale.

¶ Trips to Jerusalem

¶ a) The trip to Jerusalem

The movement of foreigners in Jerusalem showed great fluctuations, but remained almost constant from year to year. The travel season began around February or March, which was related to the climate. In these months the rainy season ended and only then could one think of travelling; previously wet roads were a major obstacle. Jerusalem also saw the majority of foreigners during the dry months, i.e. from about March to September. During these months the number of foreigners increased enormously three times a year, at the pilgrimage festivals that brought together pilgrims from all over the world: the festivals of Passover, Pentecost and Tabernacles. The highest point was reached every year at Passover.

After the rainy season, everyone made his preparations. The merchant prepared his goods. Anyone who went to Jerusalem for religious reasons, for example, to one of the festivals, took advantage of the occasion to bring his taxes (including the second tithe, which was the one that had to be consumed within the city) to the holy city. These were the taxes that had to be brought to Jerusalem: the two-drachma tax, the bikkurim (first fruits; although, normally, they were sent collectively to Jerusalem by each of the 24 priestly sections) and the second tithe. The Jewish inhabitants of distant countries, such as Mesopotamia, used the festival caravans to transport the money from the temple. The corresponding part of the bread dough was also brought to Jerusalem, although this was not necessary, since it could be given to the local priest. But, in any case, every Israelite brought the second tithe with him to Jerusalem, in kind or in money.

The preparations also included finding someone to accompany them on the journey. Because of the prevailing banditry, a private person did not dare to undertake a long journey alone. For the festivals, large caravans were formed.

The journey was usually made on foot. Obviously, the journey was shorter on a donkey. But very rarely was a means of transport used to go to or return from Jerusalem. It was generally customary to make pilgrimages on foot. And it was also considered meritorious.

The roads were generally bad. As long as the Sanhedrin, as the highest national authority, had charge of them, little was done in this respect, but when the Romans took charge of them, the situation improved considerably. However, it seems that the route of the Babylonian pilgrims (which led north from Jerusalem) was always the object of greater care. Herod the Great made an effort to secure it. He established at Batanea the Babylonian Jew Zamaris, who protected the caravans coming from Babylon to the festivals from the robbers of Trachonitis.

Such a journey, especially if it was made in a large caravan, was bound to be accompanied by interruptions and delays. Those returning from the Feast of Tabernacles (celebrated in the month of Tishri) had to reach the Euphrates before the start of Marhesvan the following month, which meant that in about half a month they had to cover the not inconsiderable distance of 600 km, if they did not want to be caught by the first rains.

¶ b) Lodging in Jerusalem

Once safely in Jerusalem, it was necessary to find a place to stay. It was usually not difficult to find accommodation in one of the city’s inns; every fairly large town had one. Members of religious communities, such as Essenes or Pharisees, were welcomed by their friends. The inhabitants of Cyrene, Alexandria, the provinces of Cilicia and Asia stayed in the hostel attached to their synagogue on the Ophel. But on feast days it was very difficult to find accommodation. Few foreigners owned their own houses in Jerusalem. The foreign princes of the Herodian family who came to Jerusalem for the feasts had arranged permanent accommodation in the palace of the Maccabees, situated immediately above the Xistus, and the princes and princesses of Adiabene in their palaces built on the eastern hill.

One of the ten miracles that were told about the city at that time was that all the faithful found accommodation without one ever having to say to another: “The crowd is so great that I cannot find a place to stay in Jerusalem.” Some of the pilgrims were able to stay in the city itself; only the Temple Square was excluded as a place of accommodation. But it is quite possible that the temple complexes offered accommodation to the pilgrims. However, even taking this into account, it was not possible to accommodate all of them within the city walls. Others could stay in neighbouring towns, for example in Bethphage or Bethany (that is where Jesus often stayed). But most of the pilgrims had to camp in the immediate surroundings of the city (and it cannot be thought that they spent the nights in the open because at least during the Passover season the nights were quite cold).

The hospitality industry was based almost exclusively on pilgrims, who were usually accommodated in large rooms with room for their horses and beasts of burden. However, those who attended the Passover, the Feast of Tabernacles and the offering of the first fruits were obliged to spend the night in Jerusalem. The city itself could not accommodate such a large number of pilgrims. So that they could comply with this requirement, the enclosure of Jerusalem was enlarged so much that it even included Bethphage. This was called “Great Jerusalem.” This concession was not valid for the eighth day of the Feast of Tabernacles and was only valid when the first fruits were presented. There was also a prescription that prohibited renting out houses in Jerusalem, since they were the common property of all Israel, and not even rooms for sleeping. For this reason many innkeepers required payment of some kind (usually skins), which, despite the prohibitions, was a profitable business.

¶ c) The movement of foreigners from distant countries

- Gaul and Germania. The walls of Jerusalem were home to Gauls and Germans. They were mainly part of the personal guard of the Herodian palace. They were first commanded by Herod, then by Archelaus, and after his dismissal, by the Romans.

- Rome. From 6 AD Judea was a Roman province; it had a Roman governor, Roman soldiers and Roman officials. In Jerusalem there was a garrison of auxiliary troops, that is, a miliaria cohort of cavalry (cohors miliaria equitata), with 800 infantry men and four turmae of 120 horsemen (30 horsemen each turmae) under the orders of a tribune, a centurion called princeps (principal) and nine more centurions. This detachment was to be divided between Herod’s palace and the Antonia fortress, the two buildings that offered the most protection. Relations with Rome were frequent. There were Romans living in Jerusalem, most of the time on official missions. In the garrison of Jerusalem, because the city belonged to a province governed by a procurator, not even the officers were Roman. In Caesarea, on the other hand, the procurator’s residence, there was the cohort called Italica. These troops accompanied the procurator when he spent the Passover there, when a detachment of soldiers was usually present. The majority of the freedmen came from Rome, captured in the Pompey War and later released. They had their own synagogue, the Synagogue of the Freedmen (which was also attended by people from Cyrene, Alexandria, Cilicia and Asia), and stayed in an adjacent hostel on Mount Ophel. There was constant correspondence between the Jews of Rome and the Jerusalem Sanhedrin, and what is more, the great Jewish authority had means of reaching the ears of the Emperor, because the Jews of Rome were quite rich and powerful.

- Greece. We find many Athenians in Jerusalem; private as well as public affairs provided them with the opportunity to establish close relationships.

- Cyprus. There were Cypriots living in the city; they were Jews from the island.

- Asia Minor. There was a large Jewish diaspora in Asia Minor. That is why there were representatives from all the regions of Asia in Jerusalem. People came from the province of Asia, from the island of Cos, from Galatia, from Pisidia, from Cilicia (which had their own synagogue in the city) and from Cappadocia.

- Mesopotamia. There was considerable trade between this region and Jerusalem. Some high priests were from Babylon (Ananel, between 37-36 BC and again in 34 BC); the well-known Hillel was from Babylon. Many Mesopotamian pilgrims who came to the festivals gathered by the thousands at Nearda and Nisibis; there they collected the money offered to the temple by the Mesopotamian community, and then set off together for Jerusalem.

- Parthian Empire. The kings and queens of Adiabene were dependent on the Parthians and had close contact with Jerusalem. Monobazus, Queen Helena and Princess Grapte had palaces there.

- Syria. Of all the non-Palestinian countries, Syria was the country with the largest proportion of Jews. In fact, there were many contacts between Syria and Palestine. Antioch and Damascus were full of Jews who went there every year for some festival. The inhabitants of Palmyra were also partly Jewish.

- Arabia (Nabataean kingdom). Contacts between Jews and Arabs were even more intense because the Jewish royalty of Jesus’ time, the Herodian family, was related to their southern neighbours. Travels by Jews to these lands and vice versa were very frequent.