© 2025 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ Organization of the Roman Army

Around the time of Augustus’s death, the empire had a total of twenty-five legions, numbering approximately 140,000 men. To these must be added a similar number of auxiliary troops and more than 10,000 Praetorian Guards. This brought the total number of troops to over 320,000.

¶ Regular Troops

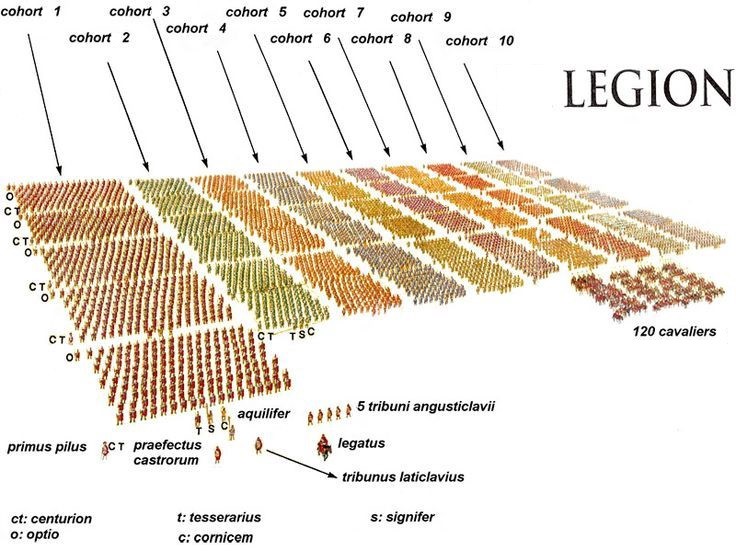

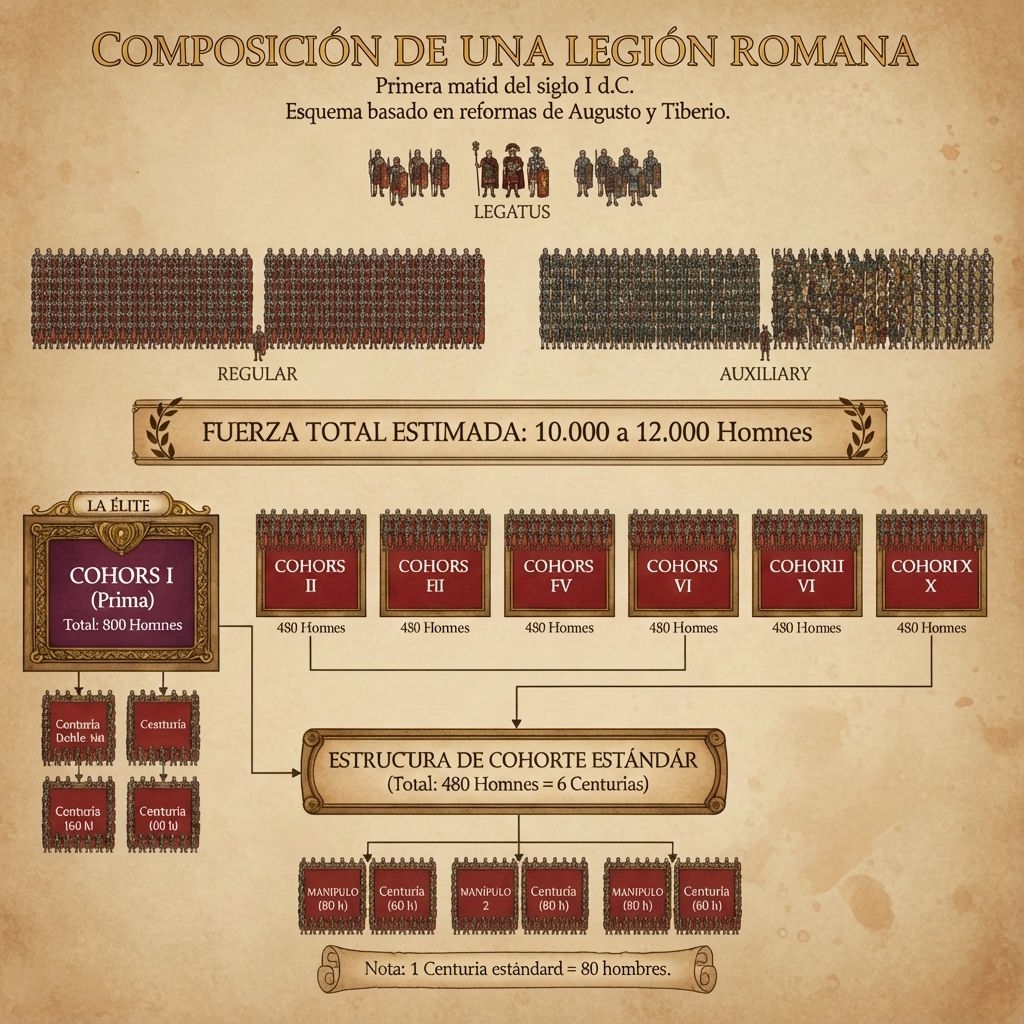

In the first half of the 1st century—the imperial era—after the reforms of Augustus and Tiberius, each legion generally numbered between 10,000 and 12,000 men (combining regular and auxiliary troops, half each). The legion’s regular troops were divided into ten cohorts, numbered I through X. A cohort (Latin: cohors) was composed of three maniples; each maniple consisted of two centuries, and a century was 80 men, so each cohort (6 centuries) totaled 480 men. The first cohort (the I), made up of the legion’s most battle-hardened men, was exceptionally composed of five double centuries (centuries of 160 men each), that is, 800 men. Each legion was commanded by a commander (legate or legatus), 7 officers (a camp prefect or praefectus castrorum and six tribunes, the latter being in charge of selecting their soldiers, the tribunus laticlavius and the five tribuni angusticlavii) and 59 centurions.

The centuries were divided into 10 contubernia (Latin: contubernium) of 8 men each (the smallest unit of the Roman army). Each contubernium was quartered in a tent or cubicle with 6 people. A quarter of the men were always on guard duty.

Each century was commanded by a centurion, who was assisted by an optio, or lieutenant, and a tesserarius, or non-commissioned officer of security. It had a standard, or signum, which was carried by a signifer. The centurions of the double centuries of the first cohort were called primi ordinis, except for the centurion of the first century, who was called primus pilus and was the highest-ranking centurion in the legion, a career soldier and advisor to the legate. In the other cohorts, the centurion who commanded each cohort was called centurion pilus prior.

Under Augustus, the traditional infantry was once again joined by cavalry—regaining its lost prestige—and a contingent of auxiliary troops. In each legion, the cavalry consisted of 480 horsemen, divided into turmae, squadrons of 30 or 32 men each, led by a decurion (Latin for “leader of ten”), a title derived from the Republican cavalry before the outbreak of the Social War, which was divided into turmae and led by three decurions each. However, in Jesus’ time, the title of decurion was retained, but they now led about thirty horsemen.

Moreover, since the time of Julius Caesar, the legions included a fairly complete artillery train: each century was equipped with a carroballista, a large crossbow mounted on a cart, and each cohort with a catapult, which not only increased the legion’s firepower in open-field combat, but also served for siege warfare.

Initially, it was an essential requirement to possess Roman citizenship in order to be a regular legionary.

¶ Auxiliary troops

Auxiliary troops were small detachments that typically accompanied a legion, performing a support role—in every sense of the word—but could also operate independently. Their main characteristic was that, with few exceptions, they were composed of individuals who were not Roman citizens. There were essentially two types of units, traditionally associated with cavalry and infantry, called ala and cohors, respectively. A separate case was the cohortes equitae, consisting of a strong infantry core and a small cavalry detachment.

During the early years of his reign, Augustus created the auxiliary corps (auxilia), drawing inspiration from the Latin forces employed by the Republic before the outbreak of the Social War. The auxiliaries, conceived as a corps of non-citizen troops parallel to the legions, differed fundamentally from the auxiliaries used by the Republic: in the Republic, auxiliary corps consisted of mere recruits enlisted for a specific campaign, who were disbanded once that campaign ended; under Augustus, this corps was entirely composed of professional volunteers serving in permanent units.

Augustus organized the auxilia into regiments of the same size as the regular cohorts because he considered that the fewer troops a unit made up, the more flexible it was.

Auxiliary cohorts, like regular ones, could be either quinquinariae or miliariae, meaning they consisted of approximately five hundred or one thousand infantrymen. Quinquinariae cohorts were made up of six centuries of 80 men each—commanded by a centurion—and miliariae of ten, giving us figures of 480 and 800 men, respectively.

As for the alae, the miliariae were made up of twenty-four turmae of 30 horsemen each – to which must be added a decurion and a standard-bearer, in total, 32 – and the quinquinariae of sixteen turmae, with total figures of 768 and 512 equites.

The cohors equitata were made up of an infantry contingent to which four turmae of cavalry were added.

Overall, the auxiliary regiments were led by a praefectus who could be:

- A native nobleman who was granted Roman citizenship. An example of this is the Germanic chieftain Arminius, who served as an assistant prefect before rebelling against Rome.

- A Roman who could be a member of the ordo equester or a high-ranking centurion.

The first of the centurions or decurions receives the title of princeps and occupies a lower rank than the subprefect, assistant to the officer in command of the unit.

At the beginning of Augustus’s reign, the core of the auxiliary troops in the West was composed of warriors from the warlike Gallic tribes (especially those residing in Gallia Belgica, which at that time included the provinces of Germania Superior and Inferior) and Illyria. Following the Cantabrian Wars (19 BC), the Empire annexed the provinces of Hispania and Lusitania, territories that soon became major sources of recruitment. In the following years, Augustus conquered the regions of Raetia (15 BC), Noricum (16 BC), Pannonia (9 BC), and Moesia (6 BC), territories which, along with Illyria, became the Empire’s main source of auxiliary recruits. In the East, where the Syrians supplied Rome with most of its army’s archers, Augustus annexed the provinces of Galatia (25 BC) and Judea (6 BC). The first of these, a region of Anatolia whose name derived from the massive migrations of Gauls there centuries earlier, also became an important source of recruits. Light cavalry, meanwhile, was supplied from the African provinces, where the regions of Egypt (30 BC), Cyrenaica, and Numidia (25 BC) were annexed. The Mauri people, who inhabited the province of Numidia, formed the main body of the light cavalry contingents sent to Italy to serve in the legions and auxiliaries. The province of Mauretania, conquered during the reign of Emperor Claudius, would also become a significant source of recruits.

The rapid conquests made during Augustus’ reign led to an increase in recruitment, both for the legions and the auxiliaries. By the year 23, there were as many auxiliary soldiers as legionaries, meaning that for the 25 legions existing at the time (140,000 legionaries), approximately 250 auxiliary regiments had been recruited.

It remains to mention the unique case of the cohorts Civium Romanorum, also auxiliary, but composed either of cives romani (Roman citizens), libertus (freedmen who could not enlist in the legions and who would have been recruited in emergency situations), or peregrini (inhabitants of the empire who did not have Roman citizenship), and who could receive the title as a reward for a distinguished feat of arms. The title would be retained by the unit thereafter, despite the discharge of the awarded troops (auxiliaries were honorably discharged after 25 years of service), and they would come under the command of a tribune.

¶ Irregular troops

As for the numerus, it initially designates any unit that does not adhere to the regularity of those mentioned above, such as the corps guards of officers or administrative officials. However, the numeri achieved the greatest success as auxiliary units, although they differed from the former in their internal organization. Thus, the numeri are what the auxiliary corps originally were: units of recruited natives who maintained their own hierarchical and organizational structure. They are, so to speak, a corps of irregulars. It seems that their development from the 2nd century onward served to compensate for the lack of traditional weapons and combat methods that arose with the gradual Romanization of the auxiliaries’ fighting style.

¶ Civilian Personnel

This small army, capable of fighting on its own in almost any military capacity, brought along (especially during the imperial period) a large number of civilians not directly connected to the legion: merchants, prostitutes, and the “wives” of legionaries (who were not allowed to marry). As they settled around the permanent or semi-permanent camps, they eventually gave rise to veritable cities.

¶ Legions existing in the time of Jesus

Augustus, Mark Antony, and Lepidus formed a second triumvirate in 43 BC. Each of them organized his own legions, but when Augustus assumed absolute power in Rome and its empire after Mark Antony’s defeat at the Battle of Actium (31 BC), he found himself with 50 legions under his command.

Augustus then decided to reorganize the army and make it professional. He disbanded some legions and merged others into a single one, reducing the number to 28. Most of these lasted for more than two centuries, and some, like the Fifth Macedonian Legion, were still in existence in the 6th century AD.

The list of legions and their location during the reign of Tiberius was as follows:

- On the northern border with Germania: I Germanica, V Alaudae, XX Valeria Victrix, XXI Rapax.

- On the southern border with Germania: II Augusta, XIII Gemina Pia Fidelis, XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, XVI Gallica.

- In Numidia: III Augusta Pia Fidelis.

- In Egypt: III Cyrenaica, XXII Deiotariana.

- In Pannonia, on the border with Dacia: VIII Augusta, IX Hispana, XV Apollinaris.

- In Moesia, Macedonia and Thrace, on the southern border with Dacia: IV Scythia, V Macedonica.

- In Hispania: IV Macedonica, VI Victrix, X Gemina—formerly Equestris.

- In Syria: III Gallica, VI Ferrata Fidelis, X Fretensis, XII Fulminata.

- In Macedonia and Dalmatia: VII Macedonica (later called VII Claudia); XI (later called XI Claudia).

As you can see, some legions have duplicate numbers; this is because some retained their original numbers. Legions XVII, XVIII, and XIX were wiped out in 9 AD in the Teutoburg Forest before they could be named. It was the greatest military disaster of the era, in which their general, Publius Quinctilius Varus (who, ironically, was the one who suppressed the Jewish revolt that followed the death of Herod the Great), lost his life. Their numbers were never used again. Legions VII and XI were renamed Claudia Pia Fidelis in 42 AD, but the original name of Legion XI is unknown.

With the loss of three legions in 9 AD, the number was reduced to 25, and Rome did not have 28 again until 66 AD.

¶ Training

The training served two purposes: to strengthen the body and to teach individual combat techniques and formations.

Marches were a crucial part of training due to their tactical importance; the faster the march, the sooner the soldiers could engage in combat. Marches were conducted regularly, regardless of the weather. Each soldier carried approximately 25 kg of equipment and was expected to cover 30 km in five hours.

The legionaries also learned to build camps where they could spend the night after days of marching.

Another part of the training was undoubtedly learning formations, as these were what distinguished a Roman legion from a group of barbarians. Legionaries knew how to execute line changes, tortoise formations, and deployments of all kinds.

The legionaries trained with weighted dummy weapons, so that the normal weapons would be lighter.

Finally, if we talk about discipline, the legionaries were taught to blindly obey orders, and those who disobeyed were severely punished by lynching, stoning, or forced labor, which was carried out by their comrades.

¶ Equipment of the Roman soldier

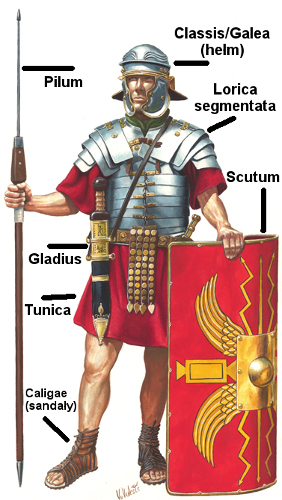

Every Roman soldier had a common field uniform: chainmail, made of iron mesh, that protected the body down to mid-thigh (known as lorica segmentata, lorica hamata, and lorica squamata, depending on the pieces), worn over a leather doublet of the same dimensions, all over the characteristic short-sleeved red tunic. The helmets, or galea, without visors, were simple and elegant, but above all, practical. They usually had the typical buculae, or bronze cheek pieces, under the chin to protect against blows from the side, and a neck guard. Following an old tradition—generally practiced in combat—each soldier wore a striking plume on his crest, made up of three red feathers about a cubit high (almost half a meter). The presence of these ornaments was primarily for psychological reasons. Although the minimum height requirement for recruitment into the legion (at least in the main cohorts) was 1.72 meters, both for battle and for guard duty, those extra fifty centimeters gave them an imposing appearance, intended to impress the enemy. The rest of their attire consisted of a wide leather belt, studded with nail heads and several iron strips that hung from the center, protecting the lower abdomen. Finally, the soldiers wore the fearsome caligae, strapped sandals with soles bristling with nails. Their weapons included a short dagger or stiletto called a pugio, the inseparable gladius, slung at the right side, and sometimes a longer gladius called a spatha. This arsenal was complemented by the pilum (plural pila), pikes two meters long, with shafts of wrought iron and steel points. The shields, called scutum, were oval and rectangular in shape, and had a convex fold, usually tinted with maroon colors.

The candidate for the legion underwent a rigorous medical and psychological examination. If he had any physical defect or a moral or mental flaw, or if he did not meet the minimum height requirement, he was rejected. If he was declared eligible (probabilis), he was measured (incumare) and assigned to a cohort. And each new recruit received a lead plaque with his identity, which he was required to wear around his neck.

¶ Military Life and Promotions

Within a legion, a man began as a simple foot soldier (miles) and after several years of service, if the soldier was a professional, the first promotion was from miles to immunis; although he had the same salary, he was exempt from the general routines of the other soldiers.

But the first true promotion made a soldier a principal, of whom there were two classes: those who received one and a half pay (sesquiplicarii) and those who received double pay (duplicarii). The first group included various types of non-commissioned officers, such as the tesserarius (orderly). Among the second were the standard-bearers (signiferi and vexillarii), the options, and other officers. The next rank was centurion, of whom the most veteran and experienced (primi ordines) formed part of the first cohort, and the most senior of these (primus pilus) had the right to attend councils-martial.

¶ Symbols

From Marius’ reforms—around 104 BC—one of the traditional standards that these units used to carry onto the battlefield was increasingly prioritized within the legion. This was the Roman eagle, which became the quintessential legionary symbol, displacing the wolf, the bull, the boar, and the horse—totemic animals belonging to a peasant society. The eagles were made of precious metals—silver at first, then gold—and were jealously guarded in the aedes signorum, or sanctuary of the camp. The loss of the eagles, as happened to Crassus or Mark Antony in the East, or to Varus among the Germanic tribes, was the greatest dishonor a legionary unit could suffer. The non-commissioned officer in charge of the eagle was the aquilifer.

In addition, there were other types of standards, such as the “signa”, “imagines”, “vexilla” or “dracones”:

- The “signum” was the standard of each century: topped with a staff or hand—reminiscent of the ancient maniple—and bearing an inscription below with the name of the cohort, it was decorated with garlands, crescent moons, and discs. The number of discs (philarae), from one to ten, indicated the century’s number within the cohort.

- The “imagines”, exclusive to the imperial legions, were heads of Caesar in the form of busts, made of gold or silver, placed at the top of the standard, and showing who was the Caesar who had formed the legion.

- The “vexillum”, for its part, was the flag that marked the general’s position on the battlefield, but it was also the standard of irregular detachments, which were therefore called “vexillations”. They were hung from a bar crossed on the flagpole. They were square in shape with a red background, and on them were the initials of the legion and cohort, as well as sometimes the representation of an eagle, the goddess Victoria, or Caesar.

- The “draco” was a bronze animal head with open jaws, to which was added a colored cloth tube that, when shaken, produced a dull noise.

The bearers of these standards were, respectively, the “signiferes”, “imaginiferes”, “vexillarii” and “draconarii”.

The veneration of the standards was carried out on a permanent basis by placing them in the “aedes”. However, there were special occasions in which the “signa”, the “vexilla” (Rosalia Signorum), and the legionary eagles (Natalis Aquilae, Honos Aquilae) were honored.

¶ Decorations

The decorations of the republican period consisted of crowns, of which there were several types:

- Grass crown: was awarded for saving an army.

- Civic crown: it was awarded for saving the life of a comrade, and was made of oak leaves.

- Corona muralis: was awarded to the first to crown an enemy wall.

- Corona vallaris: was awarded to the first person to assault an enemy trench.

- Corona navalis: rewarded the capture of a ship.

- In the imperial era, the phalerae, the armillae and the torques were added.

- High-ranking soldiers could also receive decorations:

- The chief centurion and the subordinate tribunes could obtain a silver spear.

- The chief tribune could obtain 2 gold crowns, two silver spears, and two small gold standards.

- Legates could obtain up to three sets of decorations.

- Consuls and governors could get 4 games.

- However, the highest decoration was not a medal or a crown, but what was called a “triumph”.

¶ References

Websites

- http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centuria

- http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legión_romana

- http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tropas_auxiliares_romanas

- http://www.legionesromanas.com/

- http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arco_compuesto

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iturea

- http://www.legionxxiv.org/signum/

Books

- Emil Schürer, History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus, Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985. Contains data on the troops stationed in Palestine.