© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

The first mentions of Tarichea recall that a naval battle took place there in 67 AD during the Jewish war against the Romans, which ended in bloody conflict with the death of many of its inhabitants and the sale into slavery of more than 30,000 of them. These mentions come almost entirely from the historian Flavius Josephus, but his statements seem to contradict each other.

In the War of the Jews we read:

«So Vespasian sent his son Titus to Caesarea Maritima to bring the remaining forces to Scythopolis, the largest city of the Decapolis, not far from Tiberias, where the two met. Advancing at the head of three legions, he camped three and a half miles from Tiberias, at a post in sight of the rebels, called Senabris.» (BJ III : 9.7)

On this occasion, the rebels were the people of Tiberias, who wisely decided to surrender when they found three Roman legions at the gates of their city. It must be remembered that a legion consisted of sixty centuries, and each century of one hundred men commanded by a centurion, which totaled 18,000 men. In addition, Titus commanded a cavalry group of 600 men and Trajan another of 400 men.

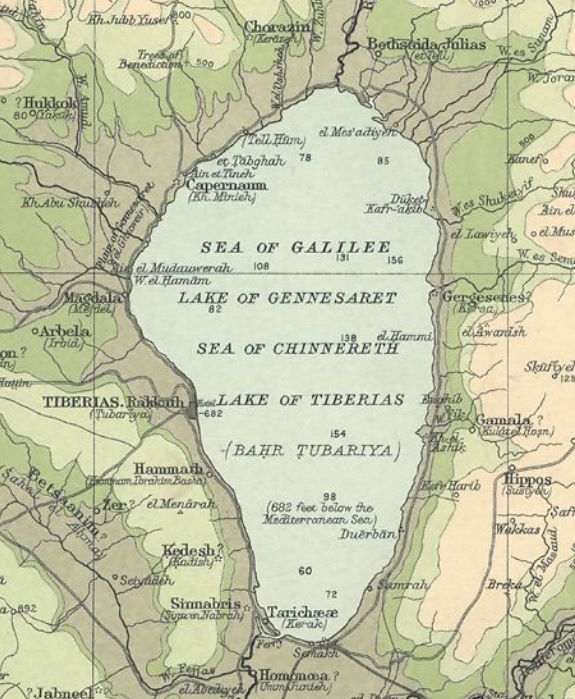

Tiberias having been surrendered, Vespasian now turned his attention to Tarichea, where many of the more stubborn rebels had entrenched themselves, fleeing from Tiberias and the surrounding towns. According to Josephus, this city, “like Tiberias, is situated at the foot of a mountain, and on both sides on which it is not washed by the sea (of Gennesaret), had been strongly fortified by Josephus, though not so strongly as Tiberias.” (BJ III: 10.1)

¶ The Battle of Tariquea

The Battle of Tarichea began while Vespasian was still organising his defences. He had ordered a defensive wall to be built, in anticipation of the difficult task of capturing Tarichea. But then one of the Tarichean rebels, named Jesu (Jesus), together with a group of brave volunteers, sailed across the sea to attack the people building the wall. It was a brave gesture that lasted only a short time. The Roman legionaries repelled the attack, forcing the Taricheans to retreat to the beach, take up their boats and move out of arrow range into the sea.

While this was going on Vespasian heard that the bulk of the Tarichaean troops were preparing for the attack on the plain in front of the city, so he sent his son Titus with 600 cavalry to disperse them. But his son soon realised that they were outnumbered and asked his father for reinforcements. The latter sent a fresh contingent of 2,000 archers commanded by Antony and Silo “to surround them against the city’s mountain, and to repel those on the walls.” Trajan, with his cavalry, also joined the charge, which caused Titus to harangue his men to have all the glory of the battle, since with such reinforcements the victory would otherwise be less than admirable. This harangue aroused such fury in Titus’ men that they overran the Tarichaeans, who were surprised by this reaction of the Romans.

In reality, only a small minority wanted to fight the Romans, the rest having been driven away by force and fear. Seeing the advantageous situation, Titus rode his troops into the city on horseback, riding across the water. Terrified by the Roman general’s audacity, many fled. Jesu and his followers crossed the sea. Others tried to follow in their footsteps by setting out to sea in boats. But it was their downfall, because they found themselves face to face with the Romans, who massacred them.

Those who succeeded in getting into the water watched from a distance as their city was taken, and they withdrew from the “enemy as far as they could.” On receiving news of the surrender of Tarichea, Vespasian entered the city with his entire army. “The next day,” he sent out hastily built boats in pursuit of the fugitives. According to Josephus, “there was an abundance of timber, and no shortage of carpenters.” This reference, coupled with the reference to the large number of ships, leads us to suppose that Tarichea was one of the famous shipyards on the Sea of Galilee.

Josephus says that the Jews were “surrounded” by land. It is not clear whether he means that all the coastal towns on the Sea of Galilee had been conquered, or that they were within a smaller area than the Sea of Galilee, a kind of harbour between wide breakwaters. For he clearly mentions that it was “the next day” that the pursuit of the escapees began, which would be strange if they had fled out to sea. In that case they would have been given a full night’s head start, enough time to make a slippery landing on any deserted beach.

Finally, the Romans found the boats and annihilated all their occupants. The massacre affected 6,700 inhabitants of the city, including those who were killed in the town.

¶ Hypothesis of current archaeology: Tariquea = Magdala. Is it correct?

Using these references, geographers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries placed Tarichea on their maps in the area south of the Sea of Galilee (for example, Hasting’s Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels, 1906, and George Adam Smith’s Historical Geography of the Holy Land, 1894, of the Palestine Exploration Survey). But later, several authors began to make hypotheses that identified the ruins of Magdala with Tarichea. The idea that led to this alternative solution is based on the description of the events made by Flavius Josephus, according to which he comments that Vespasian advanced with his troops from Scythopolis in the south to Tiberias in the north. Scholars have assumed that Vespasian used the coastal road of the Sea of Galilee, and therefore, that if Tarichea were south of the sea, his troops would have encountered the insurgents first in this town, before reaching Tiberias.

So which hypothesis is appropriate?

As we can see, the positions are basically based on the following assumptions:

Hypothesis A: Tariquea = Magdala (north of Tiberias)

- Vespasian advanced along the coastal road so he should not have crossed with Tariquea.

- The city had a mountain in front of it, and this happens in Magdala, approximately.

- Tariquea means “place of fish preservation” and it is known that an industry of this type existed in Magdala.

Hypothesis B: Tarichea = south of the Sea of Galilee (south of Tiberias), in a place called today Khirbet el-Kerak or Bet Yerah.

- Vespasian advanced through the plain of Esdraelon, reaching Tiberias from the west without encountering other rebelling towns.

- The city had a mountain in front of it. Indeed, the entire southwest of the Sea of Galilee is a steep rise that drops abruptly into the waters of the lake.

- Remains of several piers have been discovered in the southwest of the Sea of Galilee, suggesting that there were not one, but several settlements in that area.

Personally, I am much more inclined to the second hypothesis, which curiously is the one adopted by the first researchers of the previous centuries. The reason is that I find many more arguments in favour of this hypothesis when examining the orography of the Sea of Galilee. I have been able to consult topographic maps of the sea coast, and one thing that is striking is that the south-western coast is pronouncedly abrupt, with a mountainous spur bordering the lake for a few kilometres, which barely leaves room to circulate along the coast (the current road runs just a few metres from the water). It is somewhat strange to imagine that a great strategist and military man like Vespasian would cross that area of the lake along the old coastal road with his troops to present himself before Tiberias, with great danger of being ambushed. It seems more logical to imagine that they followed a route further away from the coast in order to climb the crest of the nearby hill and surprise the enemy from above. This is how the Tiberians seem to describe how they saw the Romans approaching, so that the sight of the troops frightened them so much that many fled without fighting. On the other hand, the mountain we have at Magdala is now much less pronounced than at the southern site planned for Tariquea. The current ruins of Magdala are where the so-called plain of Genesaret begins, an area where several streams flow into the lake and the coast widens considerably.

Another reason to consider is that Josephus speaks of a substantial town, with a hippodrome and other singular buildings, in the style of Tiberias (Autobiography, XXVII). He comments that it also had defensive walls, built under the patronage of Josephus himself (Autobiography, XXIX; here he also describes the reasons that led Josephus to their construction). However, neither of these two ruins have been found in the excavations at Magdala. Neither remains of a wall nor remains of a hippodrome have been found.

Emil Schurer suggests in his History of the Jewish People that Tarichea was one of the towns that formed a toparchy in Galilee. Since Tiberias was the capital of the other toparchy, it does not make much sense for Herod Antipas to build Tiberias so close to Magdala (both are only a few kilometres apart) if the latter were Tarichea. It makes more sense for it to be further away, in the south. In this way, each would be the centre of one of the toparchys of Galilee.

Furthermore, why call Magdala Tariquea when Magdala already had a common name? According to the experts who today defend the identification of the two towns, “Tariquea” means “place of fish preservation”, and from references it is known that in Magdala there was a fish canning industry. These industries, in fact, were located all around the Sea of Galilee, giving the sea worldwide fame, so that even outside the region it was known for this industry.

In any case, practically all current scholars and historians seem to agree in admitting that Tariquea is actually another name for Magdala, and that there are no longer reasons to doubt this location, which is surprising given that there are more than reasonable doubts to settle the matter.

¶ The excavations

Excavations at Magdala have brought to light remains that seem to indicate that a fleet of ships once existed there, and that some kind of battle took place, judging by the remains of arrows found. However, there is no trace of a hippodrome or solid walls, nor can the remains found be linked to the naval battle described by Josephus.

As for the excavations at Khirbet el-Kerak or Bet Yerah, they have been very scattered and not very continuous over time, and have concentrated largely on uncovering remains from the Early Bronze Age, but little from the period we are concerned with. However, remains of an ancient city of about 20 ha have been found with a fortification 8 m thick. Could these have been the foundations of a later fortification, the wall that Josephus mentions for Tarichea?

The location of this excavation is perfect for explaining some of Josephus’ passages. It seems that in recent centuries the mouth of the Sea of Galilee into the Jordan River has been moving southwards. In the old days, in Jesus’ time, this mouth was further north, right next to the site of Bet Yerah. This could explain why Josephus described Tarichea as a city surrounded by water on two sides. Perhaps this was due to the bend that the Jordan formed when it left the Sea of Galilee, surrounding the city on two sides. It also explains why Titus’ cavalry could enter the city by riding on the water. They probably rode on a shallow Jordan. In addition, during a considerable drought in the 1980s, the explorer of the Sea of Galilee Mendel Nun was able to identify the remains of the wharves of an ancient town under the water, right at the height of Bet Yerah.

¶ The Urantia Book

The Urantia Book is absolute about the location of Tarichea. While other sites are not very clear, here they offer no doubt, as if the authors assumed that it was beyond dispute. In document UB 139:8.2 it says: “[Thomas] had formerly been a carpenter and stone mason, but latterly he had become a fisherman and resided at Tarichea, situated on the west bank of the Jordan where it flows out of the Sea of Galilee, and he was regarded as the leading citizen of this little village.”

He is certainly describing the enclave of Bet Yerah, but it is striking that he refers to Tarichea as a “small village.” Would a small village have a wall and a hippodrome?

The only explanation I can find if we believe the testimony of The Urantia Book to be true, is that the town was not very large in Jesus’ time, and that it lacked many of the buildings that Josephus later mentions in his writings. In fact, it should be noted that Josephus, as we indicated above, claims to be the one who built the walls of Tarichea (we have already said that he could have used the walls of an ancient wall as a base). Therefore, in Jesus’ time, it is quite probable that Tarichea was not fortified. A similar assumption makes us think that the hippodrome and other buildings were a later addition to the village, which over the years became a populous city. It must be considered that more than thirty years elapsed between the events of Jesus’ life and those of the story told by Josephus.

But none of this is conclusive. The remains of a hippodrome have not been found at Bet Yerah either. So where was Tarichea? How can a construction like a hippodrome disappear without a trace?

Personally, I think that the only place where a hippodrome could have existed and where no trace of it remains today is at the mouth of the Sea of Galilee. The significant processes of erosion and sediment transport that have taken place in the area would explain the cleanliness of the site and the scarcity of remains. If there had been a hippodrome at Magdala, its location should be easy to locate.

Therefore, I believe that we will have to wait for future archaeological campaigns to bring to light the definitive discovery that will establish once and for all the location of ancient Tariquea.

¶ References

-

Flavius Josephus, Obras completas, Antigüedades judías y Guerras de los Judíos (Complete Works, Jewish Antiquities and Wars of the Jews), Editorial Acervo Cultural, 1961. (Works of Flavius Josephus in Urantiapedia)

-

Flavius Josephus, Sobre la antigüedad de los judíos y Autobiografía (On the Antiquity of the Jews and Autobiography), Alianza Editorial, 1987. (Works of Flavius Josephus in Urantiapedia)

-

Writings of Flavius Josephus and Philo available at www.earlyjewishwritings.com.

-

J. Hastings, T and T. Clark, Dictionary of Christ and the gospels, Edinburgh.

-

George Adam Smith, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, 1901.

-

H.V. Morton, In the steps of the master, Methuen, London

-

Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985. (The 1973 edition and the current edition offer different information about the location of Tariquea. In the 1973 edition the reviewers seem to lean towards a southern Tariquea. In the latest edition, however, Tariquea is identified with Magdala).

-

Science, Anthropology and Archeology in The Urantia Book. Part 6: An index of archaeological an historical information found in Part 4 of The Urantia Book, The Urantia Book Fellowship. (There is a brief but interesting appendix dedicated to the issue.)

-

Description, photos and videos of a page that identifies Tariquea with Magdala.

-

Description and a Flash map of the ruins of Bet Yerah.

-

The pottery of Bet Yerah typifies for archaeologists a well-known ceramic industry.

-

Mendel Nun, Sea of Galilee, newly discovered harbors from New Testament days, map included in the book.