© 2007 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

At the head of the Jewish people in Jesus’ time there was a trio of forces that together formed the ruling class: 1) a priestly nobility, or clergy, who constituted the religious authority; 2) a lay nobility, or elders, who constituted a lay authority; and finally, 3) the scribes, the wisdom authority. We will proceed to give an account of each of these groups.

¶ The clergy

The importance of the Jewish clergy in Jesus’ time lies in the tremendous theocracy in which Jewish society at that time lived. Firstly, the clergy was the Jewish nobility of the time, and secondly, it was the religious, political and legal authority of the Jewish people.

We can classify the clergy into the following grades:

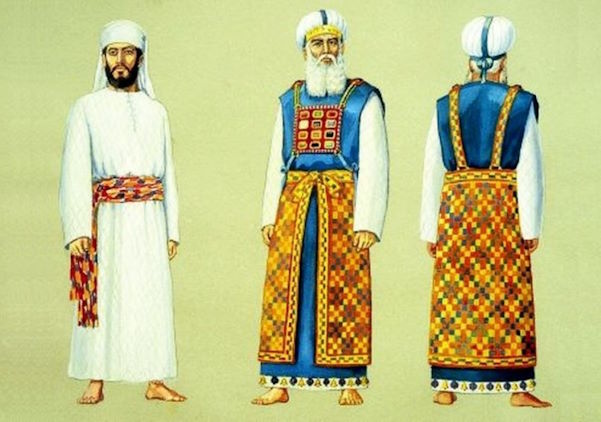

- a) The high priest (kôhen gadôl; pl. kôhanîm gadôlîm).

- b) The chief priests, composed of:

- The supreme head of the temple or simply, head of the temple (sâgan ha-kôhanîm).

- The heads of the weekly sections of priests (rôs ha-mismar), who were 24 since there were 24 weekly sections. They were in charge of worship.

- The heads of the daily shift of priests (rôs bet’ab), who were about 156, since each of the 24 weekly sections had 4 to 9 shifts per day. They were also in charge of matters of worship.

- The temple guardians ('ammarkal; pl. 'ammarkalîn). They were in charge of guarding the temple.

- The treasurers (gizbar; pl. gizbarîm). There were three of them and they were in charge of finances.

- c) The priests (kôhen hedyôt). There were approximately 7,200 of them.

- d) The Levites. There were about 9,600 Levites, with 24 weekly sections, each composed of two groups: the singers and musicians, and the servants and guards of the temple.

We now go into detail about each position in the hierarchy.

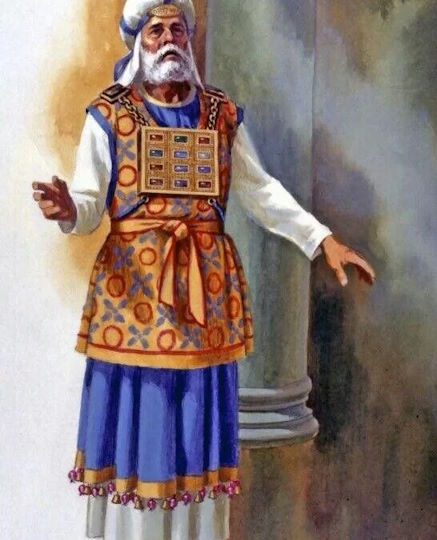

¶ The High Priest

In the days when there was no king, the most important member of the people in Judea and the one with the greatest authority was the high priest, called kôhen gadôl. He gathered around himself all authority in any matter related to the nation.

The most important privilege, however, was of a religious character. The high priest was the only mortal who could enter the Holy of Holies one day a year, the Day of Atonement. On that day, the slightest breach of the liturgical norms would have brought judgment from God, and so the high priest performed his duties in a special way, with extreme care and scrupulousness.

He also had a long series of other religious privileges: the right to make a sacrifice whenever he wanted; the right to make a sacrifice even while in mourning, something that was totally forbidden to the other priests; in the distribution of the sacred things in the temple he had the right to be the first to choose what he wanted; he presided over the Sanhedrin or great council, which was the supreme legislative and judicial authority of the Jews; and in the case of a crime, the high priest only had to submit to the great council.

The high priest, however, also had duties and obligations, almost all of a purely religious character: according to the law his duties were limited to officiating on the Day of Atonement, but custom had added others: participating in the ceremony of burning a red heifer and preparing during the week before the Day of Atonement; also officiating on Saturdays, the New Moon feasts, and the three pilgrimage feasts (Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles), as well as at the assemblies of the people; he also paid a food offering every day in the morning and evening. As for financial obligations, he was obliged to pay for a bullock that was sacrificed as an expiatory sacrifice on the Feast of Atonement, and the expenses of building the bridge over the Kidron every time a red heifer was sacrificed on the Mount of Olives.

Other obligations contracted by the high priest concerned the prescriptions concerning ritual purity. At that time, the causes of impurity that prevented the high priest from exercising his office were extremely absurd: contact with a corpse, having unkempt hair and having a tear or rip in his garments. The fact that a high priest could not officiate was so serious that the prohibitions in this matter, unlike the rest of the priests, were extremely rigorous: he could not have contact with any corpse, not even those of his own family, and to avoid this he was not allowed to march even behind the coffin (one can assume that it was practically impossible for a high priest to attend a funeral); he could not express his grief for the death of someone because that would mean having unkempt hair or tearing his garments.

Curiously, in Jesus’ time the priests were arguing a great deal about a question that had already arisen with some high priests: the question of the “dead man of the commandment,” who was the dead man who had no family when he died, and who, according to Jewish law, whoever found his body was obliged to bury him. The absurdity of these discussions at that time reached such an extreme that the Sadducees maintained that this case was an exception for the high priest, while the Pharisees, paradoxically placing mercy above ritual observances, admitted it also for the high leader.

Another of the prescriptions that sought to safeguard the high priest’s aptitude for performing worship was the severe questions about marriage. The high priest, like any Jewish priest, married. Not doing so was frowned upon since the priesthood was hereditary. However, if it was discovered that his wife was not a virgin, the marriage legally incapacitated him from exercising his office. A widow, a divorced woman, a raped woman and a prostitute were considered non-virgin women. And it went so far as to say that he could not marry a woman who had been a prisoner of war (because it was not clear that she had not been raped by the enemy). This law, however, was repeatedly ignored by various high priests of Jesus’ time, which caused the obvious indignation of the most puritanical circles of the nation (the Pharisees). But the high priest’s marriage prescriptions were such that they almost made it impossible for him to marry. At that time, after several wars in the time of Herod, practically every woman was suspected of having been a prisoner of war.

What happened when a priest became unclean and could not perform the rite? Another priest was chosen to replace him. And this priest, although high priest for only one day, was placed on the lists of high priests along with all the others. This happened several times in Jesus’ time. In 5 BC the high priest Matthias was replaced by a certain Joseph ben Ellem; Simeon was replaced by a priest in 17 AD. And there were other cases.

Finally, it should be noted that the high priest retained his title even after he had been deposed. The office, naturally, passed to another, but continued to have weight and importance in the group of priests. This explains the importance that Annas, the father-in-law of the acting high priest, Caiaphas, had in the condemnation of Jesus. Annas was high priest from 6 to 15 AD, and Caiaphas from 18 to 37 AD.

¶ The Chief Priests

The chief priests, called in Hebrew kôhanîm gadolîm, and in Greek archiereis (singular archiereus) and also archontes, were a group of distinguished priests who were in charge of various matters related to the temple. They formed a group with a certain degree of independence, probably all with a seat in the Sanhedrin, and of a social category one step higher than that of the rest of the clergy, which did not fail to provoke internal rivalries. There were various types of positions that we will examine in order of hierarchical importance.

¶ The head of the temple or sagan

After the high priest, the highest-ranking priest was the supreme head of the temple, called sagan ha-kôhanîm and also strategos and tou hierou. His office, like the previous one, was one that was required year-round by the temple cult, required his continual presence in Jerusalem, and had only one incumbent. At the time of Jesus’ crucifixion, it seems fitting that this office was held by Jonathan, son of Annas, the former high priest (mentioned in Acts 4:5-6). Jonathan succeeded Caiaphas as high priest in AD 37.

The importance of this position is due to the fact that he assisted the high priest in solemn ceremonies, occupying the place of honour on his right; he had to ensure that the high priest performed the rites correctly; he was usually the substitute for the high priest on the day of atonement in case the high priest could not carry out his function; and normally, the person who was appointed high priest was because he had previously been head of the temple.

In addition to supervising the cult, the head of the temple had supreme police authority in his hands. He was able to make arrests, and his power in political matters was therefore considerable.

¶ Section Heads

The head of the temple was followed in rank by the heads of the weekly sections of priests (rôs ha-mismar) who were 24, since there were 24 weeks in the liturgical calendar, and the heads of the daily shifts (rôs bet’ab), who were about 156, since in each weekly section there were several shifts, from 4 to 9.

These chief priests lived scattered throughout Judea and Galilee; except for the three annual pilgrimage festivals, they were present in Jerusalem to perform the cult sacrifices only once in every twenty-four weeks, when it was their turn to be on duty in their section. During this week they had to perform certain functions of the daily cult. The priest in charge of the section performed during this week the purification ceremonies for the lepers and the puerperal women who had completed their period of purification and were waiting at the Gate of Nicanor to be declared clean. It was precisely one of these priests who received Mary, Joseph and the child Jesus at the Gate of Nicanor after the forty days of Mary’s purification were completed, and it was there that Simeon the singer sang the hymn composed for them by Anna, the poetess (Luke 2:22-39).

The chief priest of the daily shift, on the other hand, had to attend the sacrifices on the day of his shift. In any case, the actual direction of the daily worship was carried out by the head of the temple and a subordinate called “the one in charge of the lot.”

¶ Temple Guardians or 'ammarkalîn

The temple guards, called 'ammarkalîn and also strategoi, were in charge of the temple gates and the guarding of the sanctuary. They were the chief guards of the vast temple building. There had to be at least seven of them, one for each door of the inner court. This inner court, a small space within the great temple esplanade, was reserved only for Jews, and no foreign gentile could enter under penalty of death. This fact was often used for abuses such as the riot that arose when Paul visited the temple (Acts 21:28). Both for the entrances to the esplanade and to the sacred inner court there were guards and gatekeepers directed by this body of 'ammarkalîn. The important posts in these guards fell to priests, and minor police duties were left to Levites. The Mishnah states that during the night the Levites acted as watchmen at twenty-one points in the Temple and the priests at three. Some of these Levite guards were posted at the gates and corners of the outer court (inside) and others at the gates and corners of the inner court (outside). The guard priests kept watch over the inner court.

A temple captain kept night watch to ensure that all the sentries were awake. This temple captain was called 'ys hr hbyt, and was in charge of the forecourt. There must have been another in charge of the Sanctuary itself, who was called 'ys hbyrh.

These security officers were also responsible for opening and closing the heavy doors, which were kept closed at night. An officer was in charge of supervising the closing of the doors, some of which were so heavy that they required the work of no less than twenty men, and which made a considerable noise when they were turned. The keys were in the custody of the elders of the priestly shifts who were in charge of guarding the atrium. When the shift changed, the priests handed over the keys to those entering on duty. Since the first morning sacrifice was offered at sunrise, the doors had to be opened before then. Only during the Passover were they kept open until midnight.

¶ Treasurers or gizbarîm

The treasurers, called gizbarîm, came after the temple guardians. There were three of them. They were in charge of the temple finances, which included real estate, treasures, jewels, tributes, offerings, as well as private capital deposited in the temple. Their activities were aimed at facilitating the acquisition of articles and products necessary for worship, the control and sale of birds and other articles for sacrifices, and the care of maintaining in good condition and repairing the gold and silver utensils necessary for daily worship.

The Jerusalem temple, in this sense, like many temples of the time, functioned like a great bank. Riches were kept inside in isolated chambers in the inner court, and all receipts and receipts were meticulously recorded in scrolls or ledgers. Treasurers were in charge of keeping all these records and collecting the payments. They were paid everything that was charged: the equivalent of the objects offered to the temple, which could be in cash, anathemas (donations to the temple that could not be in cash), other things consecrated to the temple, the second tithe, which was usually money, and anything else financial.

It was therefore the temple revenues that the treasurers were primarily responsible for managing. They received the grain offered to the temple; they were paid the equivalent of the grain, agricultural products and the dough offered; they determined the use of the objects donated to the temple; and they had the highest management of the temple tax, the two drachmas that every Israelite had to pay annually. In addition to the temple revenues, the treasurers also managed its expenses. They purchased firewood, examined the wine for the libations and the flour for the two loaves of firstfruits baked at the feast of Pentecost. Finally, part of their work was the administration of the temple reserves and the treasury.

¶ The priests

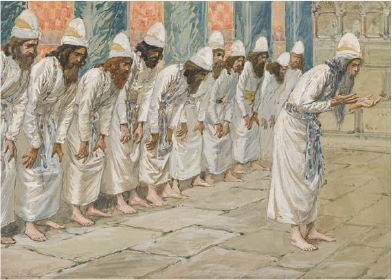

The simple priests, called kôhen hedyôt, were the great mass of existing priests scattered throughout the geography of Palestine.

The priests were organized into priestly classes. In the time of Jesus there were 24 priestly classes, whose roots went back to the distant past and whose transmission was carried out in a hereditary manner. For this reason, each priestly class was usually assigned a liturgical week, and the priestly classes were also called weekly sections. The 24 classes included all the priests scattered throughout Judea and Galilee. Each class consisted of 4 to 9 families of priests, called sections or daily shifts, because they were the ones who officiated in turns during the seven days of the week that their weekly section was in service. We have already seen that at the head of a weekly section was a chief priest, the rôs ha-mismar, and in charge of each daily section was another, the rôs bet’ab.

The total number of priests to officiate during all the days of the year is considerable. They were, as an estimate, about 7200. The number cannot be exact because each weekly section had a variable number of daily shifts, between 4 and 9. To these, we must then add the considerable number of existing Levites.

Every twenty-four weeks, and also at the three annual pilgrimage festivals, each weekly section of priests, consisting on the average of 300 priests and 400 Levites, plus a group of lay representatives from their district, went up to Jerusalem to perform the service from one Sabbath to the next. The section it relieved solemnly handed over to it the keys of the Temple and the sacrificial utensils. Thus, in the last years of Herod’s reign, the weekly section of Abia, which occupied the eighth place, was moved from the mountains of Judea to the Temple. The priest Zechariah, on the day his daily section was on duty, had been, according to Luke’s account (Lk 1:5-25), appointed to the privileged function of offering the sacrifice of incense, probably at the time of the evening sacrifice, called tamîd. And it is supposedly here that an angel appeared to him.

The priests’ cultic duties were practically limited to two weeks per year, in addition to the three annual pilgrimage festivals. The priests lived ten or eleven months a year in their homes. There they very rarely had to perform priestly duties. One example of their duties was to declare a leper clean after his healing, before he went to Jerusalem, and there, after a sacrifice, to be declared completely clean.

Tithes and other private tributes constituted the income of the priests; but they were totally insufficient to allow them to spend the whole year in idleness. On the contrary, the priests were obliged to exercise a profession in the place where they resided, usually a manual trade.

In many places there were priests who served in the courts of justice, but most of the time, no doubt, in an honorary capacity and without remuneration. Sometimes they were called upon in consideration of their priestly status; sometimes because of their scribal training, to the extent that they possessed it; sometimes, finally, to fulfill a biblical precept.

Along with the country priests who had a thorough education in Scripture, and who were usually entrusted with the synagogue service, the reading and explanation of the law, there were also others who were very uneducated. A certain degree of education was not required for being a priest. Many scribes, or rabbis, had a much higher education than the priests, and were not part of the clergy.

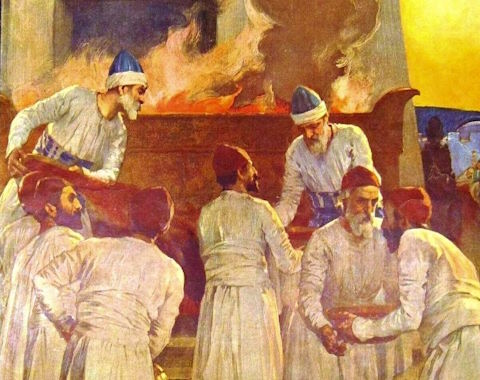

¶ The Levites

The Levites were the lower clergy. Their name comes from Levi, one of the tribes of Israel, from which they were to be descendants, just as the legitimate high priests were descendants of Zadok. They were of a lower rank than the priests and did not participate in the ritual services; they were in charge only of the music of the temple and of the lower services of the temple.

Their number reached 10,000 Levites. Like the priests, they were organized into 24 weekly sections, which were replaced every week, and each with a chief. In the temple there were 4 permanent positions of Levites: 2 chiefs in charge of the Levite musicians (the first chief of musicians and the choirmaster) and 2 chiefs in charge of the Levite servants of the temple (the chief gatekeeper and the chief guardian), called strategoi.

The Levites were divided into two groups of approximately equal numbers:

- the singers and musicians (msrrym): they constituted the highest class of the Levites. They had the function of providing musical accompaniment, singing and playing instruments, during the daily morning and evening worship and on the occasion of the particular feasts. They had a platform for themselves outside the priests’ court. They were divided into three families, the houses of Heman, Asaph and Ethan or Jeduthun, and they were divided into 24 shifts for the service. As musical instruments they usually used cymbals (msltym), which were also used to announce when the songs should begin; the harp (nbl), with twelve strings; the lyre (kinnor) with ten strings; and on important feasts a kind of flute or clarinet (hlylym).

- the temple servants (hazzanîm) were in charge of the lower functions of sacristans, which consisted of all kinds of services unrelated to worship: helping the priests put on and take off their priestly vestments, preparing the book of the law for reading, collecting the lûlab (branches of the day of Tabernacles) and stacking them up, performing the service of cleaning the temple (with the exception of the atrium of the priests, which was cleaned by the priests themselves), and surveillance work as temple police. Among the temple guards or Levitical police, three groups must be distinguished: a) doormen at the outer doors of the temple; b) guardians on the terrace, jêl, or pronaos, (or place of separation that marks the beginning of the area where pagans cannot enter); and c) patrols in the atrium of the gentiles. In addition to the chief gatekeeper and chief guardian mentioned above, who were in charge of the temple servants, we must also mention the chief of the temple mountain ('îs har ha-bayit or strategos), who was in charge of inspecting the night guard posts.

It is important to note that between the two groups of Levites, the singers and the gatekeepers, there was a great social gap in Jesus’ time. The singers were like a stratum between the priests and the gatekeepers, and were held in higher regard.

¶ The hereditary character of the priesthood

The priestly and Levitical dignity was transmitted by inheritance and could not be acquired by any other means; for this reason it was of vital importance for priests and Levites to preserve the purity of their descent, which was helped by firstly a careful recording of genealogies and, secondly, by strict rules regarding marriages. If a priest could not prove his legitimate origin, he lost for himself and his descendants the right to the function and income of the temple, and if he married illegitimately, the children of that marriage could no longer hold office.

In the temple of Jerusalem there was an archive where the genealogies of the clergy were kept up to date. These lists often disappeared when a war or revolt broke out and they had to be updated all the time, which took time. And the importance of illegal marriages at the time has already been pointed out above. Many women married by priests were considered illegitimate because they had been prisoners of war, which made them unfit as wives.

When a priest’s son reached the canonical age of 20, the Sanhedrin examined his physical abilities and the legitimacy of his origin before allowing him to be ordained. If no objections were raised, after a purification bath (baptism), he was given priestly vestments and a series of sacrifices and ceremonies were offered for seven days.

For the Levite musicians there was a similar practice, with a canonical age of 30 years, with an examination and a similar ritual.

When was a priest or a Levite musician of pure origin, so that he had no obstacle to participate in worship? Whenever he came from the marriage of a priest or a Levite with a woman of the same legal purity as himself. When a priest or a Levite singer married, it was necessary to examine the genealogy of his wife. It was very common for priests to marry daughters of priests, which allowed the priestly function of future sons. (This is the case of Zechariah, as we are told in the gospel, who was married to Elizabeth, the daughter of a priest). These marriages could be within the same priestly family (sometimes reaching the extreme of closeness of kinship) or between different priestly families. There were also unions between descendants of priests and Levites, and even more, with daughters of members of the lay nobility. The point was to ensure that the union was legitimate. The women who could not be married were the following: the prostitute, that is, the proselyte, the freed slave and the deflowered (prisoner of war); the raped, that is, the one born from an illegal marriage, or the one repudiated by her husband. And purity was required up to four or five generations back on the maternal and paternal side.

When a priest or a Levite musician married a woman who was forbidden to him by law, the procedure was ruthlessly severe: the marriage was declared illegitimate and any future sons were deprived of the right to the priesthood. These sons were called halal (profane) and their sons could never again exercise the priesthood. This explains the genuine obsession with genealogies among the families of the clergy. This also explains the abuses and shady dealings that were carried out to gain admission into the elite of legitimate families.

¶ The secular nobility, the elderly

Alongside the priestly aristocracy there was a lay nobility, much less important than the other. It was made up of the so-called elders, “the elders of the Jews” (sabê yahûdayê in Hebrew and presbyteroi tes choras in Greek). They formed part, together with the priests and the scribes, of the Sanhedrin. They were the heads of the most influential lay families, who represented the lay nobility in the council. They were also sometimes called “the chief men of the people”, “the first men of the city”, “the leaders of the people”, “the powerful ones”, the “notable ones” of the people, the “magistrates of Jerusalem” (archontes), and other similar titles.

We have in Joseph of Arimathea, the follower of Jesus, the clear example of this group. According to the gospel he was a rich landowner (euschemon), with a plantation near Golgotha, and he was a member of the Sanhedrin.

This was a small group. Specifically, the heads of the patrician families of Jerusalem sat in the Sanhedrin. Their privileged position as members of the Sanhedrin gave them special distinctions in liturgical celebrations: on the Day of Atonement, as members of the Sanhedrin, they accompanied the man who was to be led by the goat Azazel to the desert to the first of the ten huts on the road. And their underage sons could enter the atrium of the Israelites, normally reserved only for adults.

We know of eight families of this rank, who had retained an ancient privilege of supplying the wood needed for the Temple sacrifices. These are their names, with that of their corresponding tribes: Arah of Judah, David of Judah, Parosh of Judah, Jonadab of Rechab, Senaah of Benjamin, Zattuel of Judah, Pahath-Moab of Judah, and Adin of Judah. In Jesus’ time descendants of these families sat on the Sanhedrin.

The Roman procurator in Judea chose tax officials, the dekaprotoi, from among the elders, who were responsible for collecting the required tribute from the citizens subject to taxes.

These elders had little influence over the people and lived with mostly Sadducean tendencies, following the Sadducee organization and tradition.

¶ The scribes

Scribes (safra, pl. soferim) were not only found in the upper strata of society. Scribal positions were often held by people from various social groups, from aristocratic families as well as from simple priests, Levites, and even from the common people. They could even come from Israelite families without genealogical purity. Nevertheless, they were a rising power in the time of Jesus. They are designated as grammateis, the “experts of the Scripture,” “the learned” (homines literati), and also as nomikoi or jurists (Mt 22:35; Lk 7:30; 10:25; 11:45f.52; 15:3) or nomodi-dascaloi, “doctors of the Law” (Lk 5:17; Acts 5:34). Flavius Josephus calls them sophists and patrion exegetai nomon. Finally, they were frequently called wise men (hakam, pl. hakamim) and rabbis (rabbís or rabbunis).

The only factor of power for the scribes was their knowledge. Anyone who wished to be admitted to the scribes’ corps by ordination had to go through a regular course of study lasting several years. The young Israelite who wished to devote his life to the scholarly activity of a scribe began the course of his training as a student (talmîd). The training began in early life, as early as the age of twelve and thirteen. According to The Urantia Book, this caused Jesus to have to make a difficult decision at a very early age (see the incident with Rabbi Nahor in UB 123:6.8-9). The student had a personal relationship with his teacher and listened to his teaching. When he had mastered all the traditional material and the method of oral tradition (halaka) to the point of being able to make personal decisions in questions of religious legislation and criminal law, he became an “unordained doctor” (talmîd hakam). But it was not until he had reached the canonical age for ordination, about 40, that he was ordained as a scribe or “ordained doctor” (safra or hakam), receiving ordination (samikah). From then on he was authorized to decide for himself questions of religious and ritual legislation, to judge in criminal proceedings, and to make civil decisions, either as a member of a court of justice or individually.

From that moment on they had the right to be called rabbis or rabbunis or rabbán, that is, rabbis or teachers, although the term means “lord” or “chief”. In Jesus’ time, however, this term created some controversy. At that time, not only were scribes considered rabbis, but it was an honorific title given to those who deserved it. This was the case of Jesus of Nazareth, and of John the Baptist. As the years passed, the irritation of the scribes led to the title being reserved only for them. In addition, they were called “father” (pater), a designation that indicates the clear adoration and veneration that was beginning to be had for these men.

This esteem of the people meant that they were always given preference in positions, as reflected in the gospels: “They love the best places at banquets and the seats of honor in the synagogues, being greeted in the streets and being called ‘my lord’” (Mt 23:6-7; Mc 12:38-39; Lc 11:43; 20:46). They even dressed in the style of the priests and nobles, with stoles, large cloaks that fell to their feet with large fringes, and in the synagogue they could sit with their backs to the Torah cabinet and facing the attendants.

Only ordained doctors created and transmitted the tradition derived from the Torah, which, according to the Pharisees, was equal to or superior to the Torah itself. Their decisions had the power to “bind and unbind” forever in the civil and religious affairs of their time. For those who had completed rabbinical studies, all the doors to key positions in law, administration and teaching were thus opened.

They formed, together with the priests and the elders, an integral part of the Sanhedrin. All the Pharisees of the Sanhedrin were scribes. But there were also scribes who were not Pharisees. They could be Sadducees, although the Pharisee scribes were the majority, which is why in many writings the Pharisees and the scribes are imprecisely designated as synonyms. Prominent members of the Sanhedrin at the time of Jesus were the scribes Shemaya, Nicodemus, Gamaliel I, his son Simon, etc. There were also scribes in the courts.

When a community had to choose between a layman or a scribe for the position of elder, synagogue leader, or judge, the scribe was usually preferred, and that is why they increasingly occupied important positions in Jesus’ time. One of the reasons for this was not only the knowledge of religious tradition, but also the possession of an esoteric and occult tradition. This knowledge contained alleged secrets about cosmology, the origin of creation, and apocalyptic. These esoteric Jewish teachings were not isolated theological teachings, but rather constituted large theological systems or doctrinal constructions whose content was attributed to divine inspiration. This was highly respected, and the dissemination of literature on these subjects was strictly forbidden. In Jesus’ time, there was a belief that some teachings (such as the story of the sacred chariot, the name of God, and the story of creation) gave magical powers to those who received them. That is why these teachings, like those contained in Ezekiel and Genesis, were imparted by teachers in a soft and reverential voice, with their heads covered with a veil, and efforts were made to hide them in secret and offer them only in a private and privileged manner.

However, all their educational activities were to be free of charge. It was forbidden for a scribe to charge for his teaching work, or to receive gifts. They were therefore required to earn their living in some other way. In this sense, we see a clear opposition by Jesus to many of the practices of the scribes. For Jesus, the impossibility of charging for religious education work seemed unacceptable. “The worker has a right to his living” (Mt 10:10; Lk 10:7; UB 140:9.1-4). He also advocated that there should be nothing hidden, nothing esoteric (Mt 10:26-27; Lk 12:1-9; UB 150:4.2). For Jesus, the teachings were to be open to everyone and in everything, not hidden from a few. Another essential aspect, which is not reflected in the Gospels because it was silenced, is that Jesus authorized women to receive rabbinical education and instruction, and even to impart it in turn (although restricted to other women), something that caused a real commotion in the country, and we can imagine, in the scribes (see UB 150:1.1-3). For them it was strictly forbidden to teach women, and they had to remain in the synagogue in a separate room. In fact, women were not expected to attend the synagogue, since none received education in the scriptures. Along with this, another element of possible discord with Jesus, although it is not reflected in the Gospels either, is the rabbinical custom of repeating the teachings. The student rabbi had to faithfully remember everything he had learned, since nothing was written down, and any alteration to the doctrine received was prohibited. “Anyone who forgets a word of his Torah instruction, let him consider that he has wasted his life” (Abot 3:8) and “Everyone must copy the words of his teacher” (Edu 1:3). The greatest praise a disciple could receive was to be compared to “a well-plastered cistern that does not let a drop escape.” However, we see that Jesus does not offer his disciples repetitive teaching and does not use the memorization method in his preaching. His lessons seem occasional and he uses examples or parables according to the circumstance. Finally, it seems that Jesus was against the age of ordination being 40 years, since he ordained a group of much younger disciples as apostles. For Jesus, age did not represent a degree in itself.

¶ External links

¶ References

-

Joachim Jeremiah, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1977.

-

Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985.

-

Johannes Leipoldt and Walter Grundmann, El Mundo del Nuevo Testamento (The World of the New Testament), two volumes, Ediciones Cristiandad, 1973.