© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

At the present time, most countries are governed by the so-called “Gregorian” calendar, which was established by Pope Gregory based, after making certain corrections, on the Julian calendar, in use since the year 46 BC, established by Julius Caesar, and that was the calendar of the Roman Empire at the time of Jesus.

The Master undoubtedly had to know this calendar and be familiar with it, since in one way or another it affected all the kingdoms subject to the rule of Rome. But perhaps the Roman calendar of the time of Jesus occupies us with another document.

What concerns us here is the Jewish calendar of the time of Jesus and its correlation with the Julian calendar, an important issue to know when festivals and important events of his life took place.

The Gospels and all the literature from the time of Jesus that we have do not allow us to pinpoint a single date of an event in the life of Jesus. The indications of the evangelists speak in general terms with reference to the beginning of some reign but they do not specify the exact date of the events with numbers. This situation means that neither the day Jesus was born, nor the day he died, nor the date of any important event in his life is known.

To further complicate matters, there is no unanimity among scholars as to what rules governed the Jewish luni-solar calendar of the time. Some experts propose a calendar that followed fixed and well-known rules. It is known that these rules were in use at the time of Maimonides, who lived between 1135 and 1204 of our era. But it is unknown if these rules were also in use at the time of Jesus, or if instead the calendar was governed by astronomical or even agricultural observations, and not by predefined rules. [1] [2]

¶ Basic concepts

To better understand how this calendar worked, let’s clarify some basic concepts.

The Jewish calendar of that time, unlike our current one, which is solar, was governed by both lunar and solar cycles. That is, it was a luni-solar calendar.

The Earth revolves around the Sun approximately every 365 days. The Moon makes almost twelve full revolutions around the Earth while the Earth does it around the Sun. It only has 11 days left to complete twelve full revolutions.

It is easy to understand that since ancient times it has been a temptation to divide the solar year, the months, into twelve equal parts and to make these months coincide with the lunations. But the problem arises when we run into that 11-day lag every year.

To solve this problem, the Jewish calendar of the time of Jesus, like other calendars of the time also based on the Moon, used the method of inserting one more month every few years (a month called “embolismal”) to keep the solar and lunar cycles in sync, and making a few more adjustments to the total number of days in the year.

In the same way as in the Julian calendar (and later in our current calendar) one more day is added in leap years, in the Jewish calendar of the times of Jesus a full month was added every certain time intervals.

The rules of this calendar were then as follows:

-

Every 19 years (known as the “Metonic cycle”) there were certain years that had 13 months. Researchers dispute which of these years were used at that time, but almost all evidence points to years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 19 of the cycle. The rest had 12 months.

-

For certain religious holidays to fall as close as possible to certain astronomical events, some of those 19 years had to have one more day and others one day less. Specifically, something very important was that Easter fell after the vernal equinox. The fixation of these additions or subtractions to the number of days has divided the experts into two positions: the one that considers that some rules known as the “rules of postponement” (or dechiyot) were followed; and the opposite, which believes that these rules were not applied in the time of Jesus, but that subjective criteria were used (astronomical observations, observation of the moment in which the first fruits began to be ripe, the age of the lambs, etc.), set by the scribes and rabbis of the time.

Here we are not going to analyze each of these positions because they would take the explanations too far. Suffice it to say that all the determinations were aimed at the same purpose: to try to make the beginning of each year, the Jewish New Year, coincide with a very specific position of the Moon, known as Molad[3], so that from year to year the lunar synchrony was perfect.

The Molad is an average of the dates of the lunar conjunctions. In modern calendars, the astronomical conjunction of the Moon is designated as “new moon” and appears with a completely dark circle. As this conjunction takes place during the dark phase of the Moon, it is very difficult to determine the exact time it will occur and even the exact day. To add to the difficulty, the lunar cycles are not regular, but small fluctuations of the planets alter their cycle.

Today this determination is made by sophisticated calculation techniques made available to us by our superior astronomical knowledge, but at that time, everything had to be done experimentally based on crude observations. The “new moon” at that time was determined using the earliest possible visibility of the “crescent moon.” A minimum of 17.2 hours had to pass from the time of the astronomical “real” conjunction before the “crescent moon” could be seen. And even then, bad weather or other circumstances could alter these observations.

This inaccuracy in the calculation of the Molad, and the need for certain festivals to take place at the right time, make the “real” Jewish calendar of the times of Jesus a complete mystery that is difficult to solve.

Therefore, pending new discoveries and evidence, it seems that we can only guess about the dates on which the Jewish festivals occurred in the time of Jesus, and by deduction, the most important events of his life.

Perhaps one of the most discussed dates is that of his death. The Urantia Book establishes this date as April 7, 30 AD, and this date is, curiously, one of those that experts consider as a hypothesis. They are based on indications in the Gospels that the Jewish passover, the year Jesus died crucified, took place on a Friday. The possibilities admit, among other years, this April 7, 30 AD.

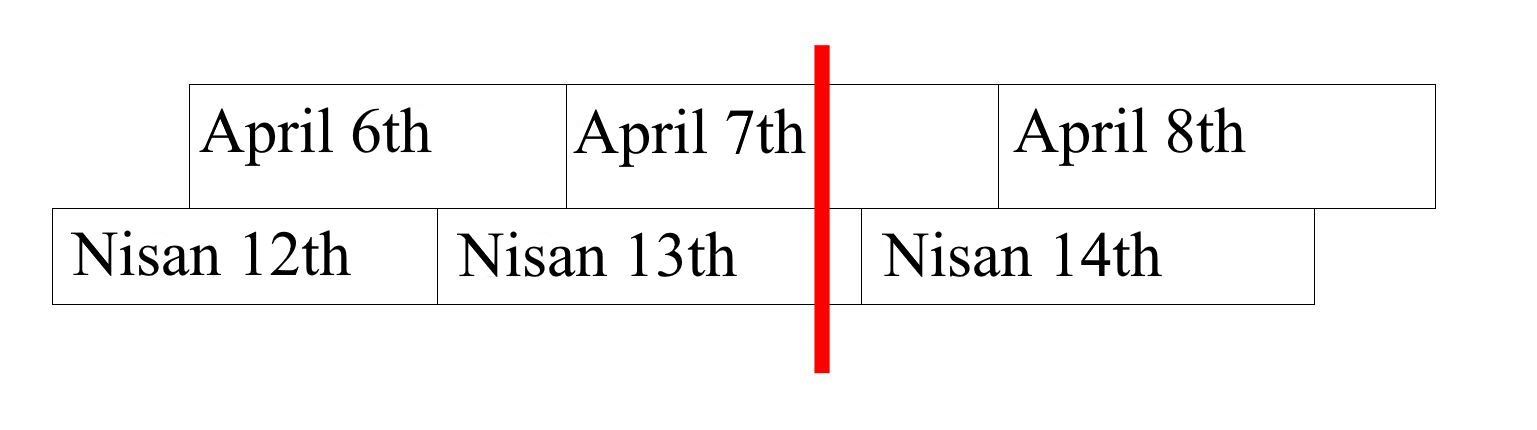

Therefore, and given the current impossibility of scientifically opting for a specific date, it has been preferred to take April 7 as valid and make it coincide with Nisan 14, which is the first day of the Easter festival. There is a wide debate and controversy on this question of whether Jesus died the day before Nisan 14, or during Nisan 14. But perhaps this is the subject of another document.

It should be noted here that the Jewish days began with a lag of almost 18 hours with respect to our current days, since the Jews began to count the beginning of the day at sunset. The graph shows this gap and the moment of the crucifixion is marked.

Some consulted calendars do not offer exactly this date for Nisan 14, but as has been explained, since everything is conjecture, an attempt has been made to develop a “possible” calendar that would fit this April 7 as Nisan 14.

¶ Procedure used

The calendar has been prepared as follows:

-

The starting point has been the calendar based on the current postponement rules, which uses a traditional metonic cycle, making the years 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 18 of the cycle have twelve months. The months, in order from first to last, were called: Tishri, Heshvan, Kislev, Tevet, Shevat, Adar, Nisan, Iyar, Sivan, Tammuz, Ab, and Elul. The rest of the years of the cycle, the month of adar was lengthened by one day and another month called Adar Sheni or second Adar (Veadar) was added after it.

-

The rule of making all months except Hesvan and Kislev a fixed length has also been used: Tishri was 30 days, Tevet 29, Shevat 30, Adar (“embolismal” years) 30, Adar (“common” years), or Adar Sheni (“embolismal” years) 29, Nisan 30, iyar 29, Sivan 30, Tammuz 29, Ab 30 and Elul 29. As you can see, it is easy to remember. Every odd month had 30 days and every even month had 29, except for Heshvan and Kislev (and not counting the Adar of embolismal years). However, many experts in the subject are more inclined towards calendars where all the months were likely to have a variable number of days. It is easy to fall for the idea that already in the time of Jesus almost every month had a fixed length to make it easier for people to remember and use them, as is done today. [4] [5] [6]

-

Similarly, the length of the days of Heshvan and Kislev followed predefined rules, which created six different types of years.

In common years there were three types:

- a year with 353 days: here heshvan and kislev both had 29 days.

- a year with 354 days: here heshvan had 29 days and kislev 30.

- a year with 355 days: here both had 30 days.

In embolismal years there were three types:

- a year with 383 days: here heshvan and kislev both had 29 days.

- a year with 384 days: here heshvan had 29 days and kislev 30.

- a year with 385 days: here both had 30 days.

-

The position of the Metonic cycle at the time of Jesus has also followed the current calendar, making AD 30 the beginning of the Jewish year 3791, which was the tenth year of the corresponding Metonic cycle.

| Year of the metonic cycle | Gregorian Julian year |

Jewish year 1 | Age of Jesus 2 | Days of the Jewish year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 24 | 3785 | 30 | |

| 5 | 25 | 3786 | 31 | 355 |

| 6 | 26 | 3787 | 32 | 385 |

| 7 | 27 | 3788 | 33 | 355 |

| 8 | 28 | 3789 | 34 | 383 |

| 9 | 29 | 3790 | 35 | 355 |

| 10 | 30 | 3791 |

1 Year beginning in Gregorian fall.

2 Jesus’ birthday that August.

3 Embolismal years in bold.

-

Finally, the astronomical data provided by NASA’s Six Millennium Moon Events,[7] [8] have been used to try to adjust the best possible start of each year with the lunar conjunction of September-October. It should be remembered that the Jewish calendar year began on Tishri 1st, which usually fell in the early fall. Nisan 1 was the beginning of the religious calendar.

-

Finally, the calendar has been adjusted so that April 7th, AD 30 would be Nisan 14th, 3790, shifting the rest of the calendar accordingly to maintain integrity in the number of days in the months. The result of this work is shown in this Chronology of the life of Jesus.

¶ Conclusions

We really cannot say for sure when the important festivals took place in the time of Jesus, and therefore many of the main events of his life, if we believe the Gospel accounts.

Surprisingly, the calendar offered here as a solution is never more than two days behind the calendar based on current postponements, and never more than two days behind the astronomical data calculated by NASA. This means that even if the calendar were not exact, a situation more than possible, the deviation would not be greater than two days, and preferably forward in time.

There are many factors that can blur the results: on the one hand, the astronomical calculations may not be completely accurate, and do not take into account all the lunar disturbances that affected the time; on the other, the observations made by the scribes and rabbis of that time could have been affected by cloudy days and bad weather; or it could even be the case that all the assumptions about the use of the current calendar were wrong and a very different one was actually used then.

What is clear is that any approximation must be guided by astronomical data, which can suffer deviations of several hours, but in no case more than a day. Therefore, we can say with some certainty that it is a fairly close calendar to the one that Jesus himself could use during his public life. [9]

¶ External links

¶ References

Carl D. Franklin, Why the crucifixion of Christ could not have ocurred in 31 AD. This paper is available at http://www.cbcg.org/hebrew_cal.htm. ↩︎

Carl D. Franklin, The calendar of Christ and the apostles. This paper is available on the same website as the previous one. ↩︎

http://www.rosettacalendar.com/, Rosetta Calendar, a date conversion web application that uses the current posponement calendar. ↩︎

http://www.calendarhome.com/converter/, the most complete calendar converter. ↩︎

http://www.ortelius.de/kalender/form_en2.html, another calendar calculator. ↩︎

http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/phase/phases0001.html, NASA astronomical data. ↩︎

http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/SpringPhenom.html, astronomical data from the United States Naval Observatory. ↩︎

http://www.judaismvschristianity.com/Passover_dates.htm, possible dates for Jesus’ Passovers. ↩︎