© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ Meanings

In Aramaic, the synagogue was usually designated as knst or knyst (keneset), which came to mean “the religious congregation.” Here the meaning was oriented towards the communal aspect of the word. It was not a question of designating a place reserved for worship, but rather the act of gathering itself. What was important for the Jews was not the place of worship. The only place of worship truly revered by the Jews of Jesus’ time was the Temple in Jerusalem. Synagogues were simply a place to meet to discuss matters of community interest, which were almost always of a religious nature. It must be said that in the following centuries, after the destruction of the Temple, the attitude of the Jews towards the synagogue changed until it became the center of their customs.

Hence, the Greek words chosen to translate keneset came to mean something similar to “congregation” or “assembly” among non-Jews: synagogé, sýnodos, or ecclesían.

It could also be designated as proseucha or proseuché. Here it refers more to the building itself that housed the meetings.

¶ Origin

The origin of synagogues dates back to the time of the exile, and they emerged as a form of gathering to instruct and communicate the Torah, the Jewish scriptures, and to maintain Jewish customs amidst so much foreign influence. That is, they were not originally intended to serve religious worship, but rather consisted of a simple social gathering for educational purposes and to strengthen community ties.

However, in Jesus’ time, it was widely believed that the institution of the synagogue came from Moses himself.

¶ Organization

We must distinguish between the elders (archontes, presbiteroi, geroysiarches, the latter being the head of all), who were in charge of the affairs of the congregation in general, and then a group of officials to attend to specific matters, among whom there always had to be: the archsynagogue (archisynagogus) or president of the synagogue, the almoner (gby sdqh), and the minister of the synagogue (hazán).

¶ The archsynagogue or president of the synagogue

In Aramaic it was called ros ha-keneset. He is the director of worship. The responsibility of this position was to attend to public worship. He was the person, for example, in charge of inviting the appropriate speaker to perform the readings, the prayers, as well as the preaching. One of the elders was usually chosen for this position. Generally speaking, it was his responsibility to ensure that nothing improper occurred in the synagogue, and he was probably also in charge of the care of the synagogue buildings. See Mk 5:22; Mk 5:35,36,38; Lk 8:49; Lk 13:14.

An example of an arch-synagogue is known to us from the Gospel, which mentions Jairus, the arch-synagogue of Capernaum, who most likely became a follower of the Master after the miraculous healing of his daughter thanks to Jesus. See Mk 5:21-43; Mt 9:18-26; Lk 8:40-56. This inference appears as such in UB 154:1.2.

¶ The Almsgiver

In Aramaic, this was gby sdqh. He made the collection for the poor. There were two kinds of collections:

- the weekly alms basket (qwph or cupa), from which the necessary amount was taken to relieve the local poor once a week.

- the “tray” (tmhwy), from which any needy person, especially foreigners, could receive a daily portion. But only those who did not have enough food for two meals a day could apply for this charity.

¶ The synagogue minister

In Aramaic, hzn hknst, hazán or chazan ha-keneset. In Greek, synonyms such as yperetes or diachonos were used. His task consisted of preparing the sacred texts for the service and replacing them in their places once it was finished; he was also in charge of announcing the beginning and end of the Sabbath with a trumpet blast. His duties were very varied. He could be in charge of carrying out the punishment of those condemned to flogging, or he could also be dedicated to teaching children to read.

¶ The reader of the scriptures, the reciter of the prayer, and the preacher

In Aramaic, slyh shwr. There were no official functionaries for these tasks. This work was assigned to one member of the community, or each of the three tasks to different people. It could also fall to someone prominent who was passing through. This is how Jesus was able to address them on many occasions during his visits to the Jewish towns.

¶ Powers

In strictly Jewish communities, the institution held all power. Religious power included authority over civic and legal matters, since Jews did not distinguish between religious and other legislation.

¶ Disciplinary Acts

When a member refused to submit to the prevailing religious legal order, and after several warnings, the elders, after deliberation, decided on excommunication or exclusion from the congregation. Although it should be noted that there were two types:

- nidduy or sammatta, or temporary exclusion, with the possibility of readmission;

- herem, or perpetual excommunication.

In either case, it only represented social exclusion, not a physical punishment. The person was forever marked by suspicion, and it was normal for them to be socially marginalized, which forced them to leave their place of origin and change residence frequently. They were also barred from entering the synagogue. But for a Jew, this represented the worst of punishments.

This allows us to better understand the passages in the gospels where Jesus is shown inadvertently changing Capernaum for Tyre and Sidon (Mk 7:24), probably because of his excommunication, which curiously is never mentioned in the gospels (but is in UB 154:2.1). It is mentioned, however, as an action against his disciples, aphorizein in Lk 6:22 and aposynagogon poiein or ginesthai (Jn 9:22, 12:42, 16:2).

¶ The building

It was called in Aramaic bet keneset (byt hknst), in Greek synagogé and proseuché, especially the latter (translated as “house of meeting”). Other less common designations were proseuchterion and sabbatherion.

Regarding their location, Schürer tells us:

Synagogues were preferably built outside cities and near the banks of a river or by the sea, so that everyone could perform the prescribed ablution before taking part in worship.

Although there are no indications of this custom in rabbinic literature, although there are in other sources, what the rabbis did remember to mention is the custom of building them at the highest point in cities. It seems that in the event that both customs came into conflict, the one that prevailed was proximity to water (such was the case of the synagogue currently preserved in the ruins of Capernaum, which is close to Lake Tiberias), or two synagogues were built (as in Gischala, where the remains of one synagogue are found at the top of a hill and another at its foot, near a spring).

The only two synagogue ruins that security dates back to the time of Jesus are those of Masada and Herodium. The others are almost all later than the 3rd century AD, and do not serve us well to form an exact idea of what they were like in Jesus’ time (for example, the synagogue that can be admired today in the ruins of Capernaum dates from the last decade of the 4th century AD and the middle of the 5th century AD, long after Jesus’ time, which makes it very unlikely that it was the one the Master knew). Therefore,We will examine the two cases available to us in more detail to get an idea of what these buildings were like at the time we are dealing with.

The original Masada synagogue was a rectangle measuring 15 x 12 m with two rows of columns. The floor was made of gray plaster. The entrance was in the east wall; the main hall was reached through an atrium. Later, the Zealots made modifications.

The synagogue at Herodium was similar, although it seemed to have a lesser religious purpose, given its location.

The honorific seat, undoubtedly intended for the president of the synagogue, was known as the “seat or chair of Moses” (in Aramaic qtdr dmst, in Greek Moyseos cháthedra). The one found in the synagogue at Hammat, near Tiberias, bore an Aramaic inscription commemorating one of the benefactors.

Certain architectural elements cannot be considered typical of Jesus’ time, such as a niche in the wall facing Jerusalem for the storage of Torah scrolls, or the basilica floor plan facing the Holy City with an ark for the Torah in the middle.

We have mentions of construction elements that were part of synagogues: the exedra, the pronaos, the peribolos (this contained dedicatory inscriptions and votive offerings, as in the atrium of the Temple in Jerusalem), the ypaithroy, a fountain, a courtyard, a dining room, and porches. But it remains to be seen whether much or little of this was part of the typical synagogue of Jesus’ time.

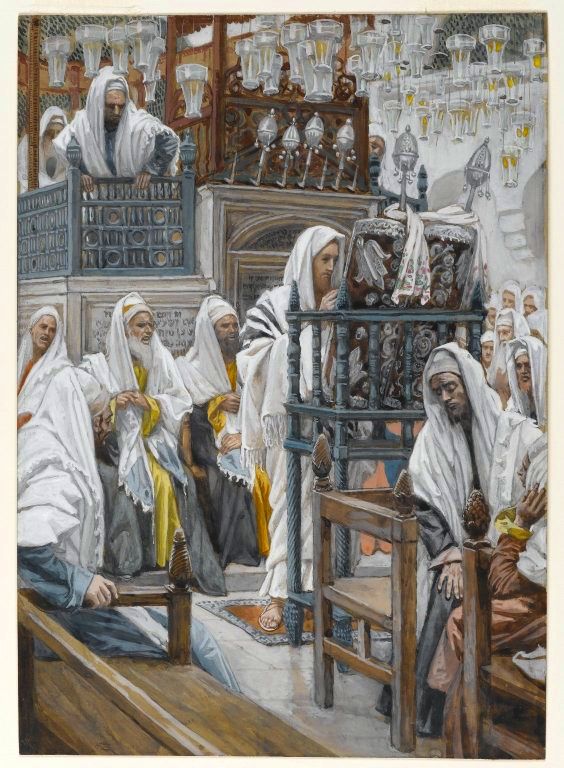

What does seem certain is that at that time, a strict prohibition on figurative representations, whether of animals or people, in whole or in part, prevailed. Ornamentation, therefore, must have been sparse, limited to the representation of static symbols of the Jewish world (the menorah or seven-branched candelabrum, the sofar or call horn, the lulab or branches of the Day of Tabernacles, the etrog or forbidden fruit, and the maggen or Star of David). Only much later did this attitude toward the visual arts change in the Jewish world. This was certainly, however, on the lips of Jesus during his pilgrimage to Jewish and foreign synagogues.

Schürer asserts, in contrast to archaeologists who emphasize the scarcity of ruins, that the institutional importance of the synagogue must have meant that synagogues existed in all Jewish towns, even the smallest. In large cities such as Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome, there must have been quite a few. A fairly reliable number for Jerusalem is seven synagogues. In Alexandria, there is talk of several, without any specifics, then at least two, and probably three or four. In Rome, a similar number. When there are several, they are usually distinguished by some emblem or representation. In Sepphoris, for example, there is talk of a “synagogue of the vine” (knyst dgwpn), and in Rome there must have been several because one is distinguished as the “synagogue of the olive tree” (synagogé elaias).

The furnishings of ancient synagogues were very simple. The main object was the ark (tybh or rwn), which housed the Torah scrolls and other sacred books. These were wrapped in linen cloths (mtphwt) and closed in a case (tyq or téche). Although they are only mentioned later, they presumably had a platform from which readers and preachers spoke (bymh or béma, the rostrum), on which a wide lectern was placed to rest the heavy scrolls. Lamps are also mentioned. Some celebrations made use of the symbolism of lights, so it is not surprising that there were several. Horns (swpwt), which were blown on New Year’s Day, and trumpets (hswsrwt), which were used on fast days and at the beginning and end of each Sabbath, were also used as a warning signal.

¶ References

- Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985.