© 2009 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

The incident with the merchants in the Temple is one of the most misunderstood and distorted episodes in the life of Jesus. Many books have called it “the expulsion of the merchants from the temple” or similar terms, but it is the way in which this event occurred that completely distorts the authentic and genuine personality of Jesus.

¶ The contextual situation

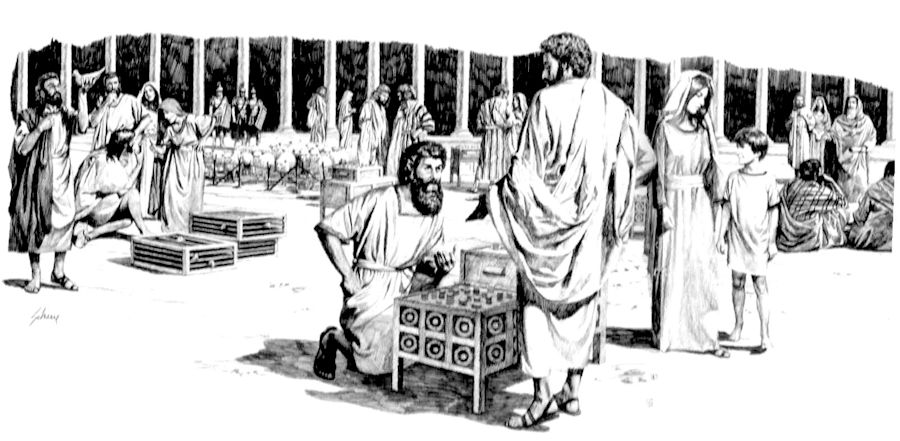

The temple in Jerusalem was the religious center and focus of the Jews in the time of Jesus. All the spiritual hopes and desires of the people of that time passed through this sanctuary in the holy city. Unfortunately, this attention had also led to commercial opportunism on the part of those who saw pilgrimages and religious rites as a way to earn a substantial amount of money.

Major businesses related to religious services and ceremonies were conducted in this temple. There was a flourishing trade in providing suitable animals for the various sacrifices. Although it was permissible for the interested party to provide their own animal for the sacrifice, this animal had to be free of any “defect,” in the sense that it had to comply with certain requirements of Levitical law, and it also had to pass inspection by temple officials. These inspectors followed an interpretation of the law, which, as one can easily imagine, was not free from all kinds of abuses. Consequently, it had become almost universal practice to acquire sacrificial animals in the temple itself, buying them from vendors who set up stalls in the courtyards. This lucrative business, as was to be expected, did not go unnoticed by the priestly leaders. Part of the profits obtained within the holy precincts were required to go to the temple treasury, but the larger portion ended indirectly in the hands of the families of the high priests. Only a small, though highly desirable, portion found its way into the hands of the sellers themselves. UB 173:1.1

This sale of sacrificial victims prospered because, when someone came to make a sacrifice and purchase an animal, even if the price within the temple was slightly higher, he was guaranteed that the offering would not be rejected because of possible real or imagined defects. At one time, exorbitant surcharges were levied on the people, especially during the great national festivals. At one time, the greedy priests went so far as to demand a week’s worth of labor for a pair of doves, when in fact they should have been sold to the poor for a few cents. These practices, to a greater or lesser extent, continued into the time of Jesus and even after his death, until three years before the destruction of the temple in 67 AD, when a group of revolutionaries completely destroyed these supply markets. UB 173:1.2

However, the traffic in animals and other merchandise was not the only means by which the holy places were profaned. At that time, there was an extensive system of banking and commercial exchange carried on directly within the temple precincts. UB 173:1.3

During the Hasmonean dynasty (164-63 BC), the Jews minted their own silver coins, and it had become standard practice to require that the half-shekel temple fees and all other levies be paid in this coin. This regulation required the authorization of a small number of money changers to convert the many types of currency in circulation throughout Palestine and other provinces of the Roman Empire into this Jewish coinage. The temple tax per person, payable by everyone except women, slaves, and children, was half a shekel. However, the enforced coin was the Tyrian shekel, a special coin worth two current shekels, about the size of today’s euro, but easily worth the equivalent of about 96 euros[1]. Poor families with many adult males had difficulty affording this payment, but what was truly outrageous was that, in Jesus’ time, priests had been exempted from paying temple fees. For the rest of the population, between the 15th and 25th of the month before Passover, reputable money changers set up their stalls in the major cities of Palestine, in order to provide Jews with the appropriate money to pay the temple fees upon their arrival in Jerusalem. After this ten-day period, these money changers would travel to Jerusalem and set up their currency exchange tables in the temple courtyards. They were allowed to charge a commission of 30%, or even more, 40% of the value of the money sold, and in the case of larger coins, they could even charge double that amount. Similarly, these temple bankers earned money through the exchange of all kinds of currency for the purchase of sacrificial animals and for the payment of vows and offerings. UB 173:1.3

These temple money changers not only conducted this lucrative banking business for the exchange of more than twenty different coins that pilgrims coming to Jerusalem could use, but they also handled every other type of banking transaction. Both the temple treasury and its rulers earned enormous sums of money from these exchanges. It was not uncommon for the temple treasury to contain over 207.5 million euros in contemporary coins[2], while the common people languished in poverty and continued to pay these unjust contributions. UB 173:1.4

¶ Jesus’s Position

It was in the midst of this noisy crowd of money changers, merchants, and livestock sellers on this Monday morning that Jesus attempted to teach the gospel of the kingdom of heaven. He was not the only one who resented this desecration of the temple; the common people, especially the Jewish visitors from foreign provinces, were also deeply troubled by this degradation of the holy place. UB 173:1.5

This was something the Master had criticized on numerous occasions, as well as other absurd and self-imposed religious practices of his nation’s leaders. However, he had never attempted to take any action to put an end to this trade. Jesus well knew that such an attempt would have been futile and foolhardy, for it would have resulted in immediate arrest, and of course, the priestly leaders would not have missed the opportunity to accuse him of being a troublemaker before Rome. Faced with this seemingly insoluble panorama, Jesus had opted for calm and to try to continue his preaching as long as the chaos allowed.

¶ What Happened

What happened then that morning? If we read the Gospels and some books that comment on them, we will see that many authors do not hesitate to affirm that Jesus arrived at the Temple that day with the firm intention of expelling, by force if necessary, these merchants and money changers. However, they do not provide satisfactory explanations as to why Jesus chose to carry out this bold action on this day, and not on any of the many other occasions when he visited the holy city. Nor do they explain how it was possible that a single man, apparently with a whip in his hand, managed to sweep everything away, sweeping away men and animals in his wake.

I believe that all these perceptions are very far from the authentic personality of the Master, and that, following the lead of Gospel literature, many authors have distorted Jesus with characters of sudden angry reactions.

That morning Jesus did not go to the temple with the sure purpose of dismantling that corruption. Rather, the Rabbi approached to preach within the sanctuary courts, as he had customarily done. The Sanhedrin, fortunately, had been frightened by the popular explosion that had occurred the day before, the triumphant entry into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey, and they hesitated to arrest the Master for fear of possible reprisals from the people. The Sanhedrin imagined that the people’s warm reception of Jesus meant that he enjoyed the favor of the multitude, and they were afraid that any initiative against him might stir up the crowd. UB 173:2.1

The point is that this fear of the Sanhedrin allowed Jesus to enter the temple on Monday without any problems and without any signs of being harassed. However, after barely a few minutes of preaching, several coincidental circumstances triggered such profound indignation in Jesus that, combined with his condemnation of the temple trade, they gave rise to certain events. These circumstances (some louder shouts, a child unable to control a herd of oxen, and a group of pilgrims mocking a follower of the Master) were more than enough. At no time did Jesus attack anyone, neither with his hands nor with any whip. Moreover, no one was hurt or bruised. Things happened in a completely different way.

Traditionally, this has been an erroneous image of Jesus, but it does not fit with the gentle and peaceful character of his preaching.

What Jesus did was simply energetically approach the boy who was leading the oxen, and after seizing his whip, he led the cattle back to their destination so that they would not bother him anymore. When he arrived there, in the corrals, with such deep indignation that he carried, he began one by one and opened all the cages, letting the animals free, who fled in terror, seeing their opportunity to escape. This evidently caused confusion among the merchants, who, instead of attacking Jesus, out of concern for the animals, tried to reclaim them.

And the real expulsion of the merchants occurred from this point on, and it wasn’t Jesus’ doing. A large group of pilgrims who resented that trade, inflamed by Jesus’ actions, took advantage of the chaos to overturn all the tables in the stalls, spilling merchandise and scattering coins. Then, they drove the animals completely out of the pens toward the cattle entrance and exit gates. And finally, with threats and probably brandishing their hands, they drove the merchants out and stationed themselves at the gates to prevent anyone from entering. And all this in just a few minutes. UB 173:1.7

This tumult, which was of course noticed by the temple guards, and what is worse, by the Romans who were guarding the temple, disappeared as quickly as it had arisen. By the time they appeared in the courtyards, all was quiet and calm. Calmer than usual.

Nor should any mistake be made in regarding this expulsion of the merchants. The pilgrims did not expel every single merchant who was then present on the so-called Esplanade of the Gentiles. This enclosure was very large (about 1,000 x 1,300 feet), and only those in the immediate vicinity of where Jesus was preaching were removed.

During this entire period of expulsion, neither Jesus nor his apostles or immediate followers moved a muscle. This was because they had specific instructions from Jesus not to engage in any public performance. UB 173:0.1 Therefore

Therefore, Jesus simply eliminated from the situation the one element that was bothering him in his preaching: the immense clamor of the animals that had been going on for several minutes. His intention was not to expel these people, but to draw their attention to the fact that such chaos could not be permitted. The incident, had it not been followed up by the pilgrims who supported him, would have ended in a minor dialectical battle between Jesus and the vendors. The latter would have made the animals return to their cages, and everything would have continued as before. On the contrary, the impetus of those pilgrims meant that no merchant was allowed to pass through that morning.

The proof of all this is that Jesus, the next day, returned to preach in the temple and did not attempt to expel anyone from there. The vendors, however, as we can suppose, set up their tables again and continued selling.

¶ Jesus’ Attitude Toward the Use of Force

We would not complete this commentary on the events of this day, however, if we did not refer to Jesus’s attitude toward the use of force.

To begin with, Jesus was a peaceful man. He was a man of peace. He did not wish harm on anyone, not even his most bitter enemies. He did not seek to impose himself on anyone or rival anyone. He never used force to impose himself on another person. Jesus always used the technique of returning good for evil.

When someone attacks us, our malformed instinct drives us to attack the aggressor in return. Retaliation is usually considered justified, implying that it prevents something worse from happening to us, which is logical. But the technique is imperfect, because evil responded to with evil only generates greater evil. What usually happens if we respond to an attack is that the aggressor, in turn, wants to continue. Jesus always encouraged his followers to combat evil—not passively—but with good. In this case, Jesus avoided inflicting any harm on the vendors, nor of course on the boy who was driving the animals (these people probably didn’t really intend to bother Jesus), but rather eliminated only the element that bothered him: the noise and disorder in the plaza.

Jesus’ philosophy regarding physical aggression was similar. If someone attacks you, it’s logical to move away, even to parry the blow. But you are not allowed to respond with another blow. There is no justification for retaliation! If there is an element that disturbs our peace, without our having provoked it, it is only right to eliminate that element. But not to provoke a new one. In an unjustified attack on Jesus on one occasion, the Master simply said: “If I have said something wrong, why are you hitting me instead of telling me what it was?” That is, he calmly asked his aggressor the cause of the aggression, but he did not attack his aggressor either physically or verbally.

Now, in the face of the unjust and enslaving practices that many powerful people of the time exercised against Jesus’ contemporaries, the Master demonstrated the determination to fight for their defense. The Rabbi also detested that degrading marketing of the temple that only served to oppress the nation. He rejected such practices, and that is why he had this sudden reaction. In this way, Jesus justified every natural reaction to the enslaving and oppressive activities of all peoples and of all times, but he gave us an example of temperance. There is no justification for retaliation, for an angry response. We must address the root of the problems, not create new ones with our desire to fight.

This is how The Urantia Book puts it:

This cleansing of the temple discloses the Master’s attitude toward commercializing the practices of religion as well as his detestation of all forms of unfairness and profiteering at the expense of the poor and the unlearned. This episode also demonstrates that Jesus did not look with approval upon the refusal to employ force to protect the majority of any given human group against the unfair and enslaving practices of unjust minorities who may be able to entrench themselves behind political, financial, or ecclesiastical power. Shrewd, wicked, and designing men are not to be permitted to organize themselves for the exploitation and oppression of those who, because of their idealism, are not disposed to resort to force for self-protection or for the furtherance of their laudable life projects. UB 173:1.11

¶ Notes

The Tyrian shekel was worth about 64 Roman ases. Each Roman as, taken at the equivalent of today’s (2025) cost of living, could have been worth about one and a half euros. Therefore, the Tyrian shekel could represent about €96 in today’s money, enough for two adult males to pay the tax. This may not seem like a very high tax, but it must be taken into account that the average salary of a Jewish artisan in Jesus’ time could have been unthinkable for it to exceed the equivalent of €500 per month (in 2025). Therefore, €96 in taxes for every two males could have been dramatic for a family. ↩︎

$100 in 1935 US dollars is equivalent, taking into account total inflation, to $2,340 in today’s money (2025). The Urantia Book states that the Temple treasury could have contained more than $10 million in 1935 dollars. That’s $234 million in 2025 dollars, or about €207.5 million. ↩︎