© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

In a previous article we have already investigated what Capernaum may have been like in the time of Jesus, and one of the most significant remains of the ruins of Capernaum is a building that has come to be called the “house of the apostle Peter”. The authors of Excavating Jesus, Crossan and Reed, summarise the importance of this discovery as follows:

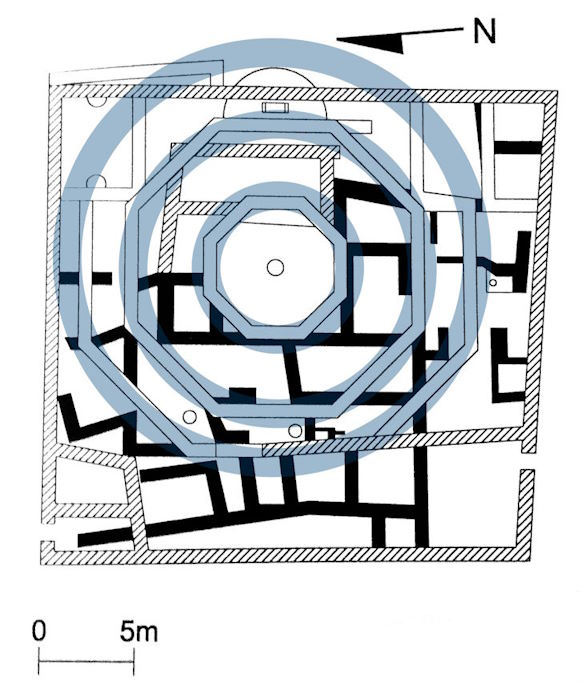

In 1906, the ruins of an octagonal building were discovered on land in Capernaum under the custody of the Franciscans. This was the Byzantine church that had become the “house of the Prince of the Apostles” spoken of by ancient pilgrims. Between 1968 and 1985, Franciscan archaeologists Virgil Corbo and Stalisnao Loffreda worked on this octagonal structure and its surroundings, bringing to light its extremely complex strata. In the 5th century BC, an octagonal church was built on top of a house-church dating from the 4th century, both of which were built on top of a simple courtyard house originally built in the 1st century BC. A series of curious examples of Christian invocations in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Syriac had been scrawled on the stucco covering one of the rooms as early as the 2nd century AD. Since there were no household utensils and the room had been plastered several times, the early generations of Christians must have considered the room to be important in some way. The archaeologists concluded that it was the house of the apostle Peter.

Is this building really the ancient house of Peter, and most likely the first Christian church in the world? This is what the Franciscans who have excavated the site seem to suggest.

The truth is that there are a good number of arguments in favor of this hypothesis:

- Remains of hooks and fishing tools have been found in the stratum corresponding to the period of Jesus’ time, which attests that the houses on which the octagonal church was later built could have belonged to a family dedicated to fishing.

- Ancient monograms, symbols and inscriptions have been found on the plasterwork of the walls. Although there is no consensus on the correct meaning of these symbols, it is possible that they are some kind of Christian markings, which attests to a ritual use of the site by early Christians.

- We have received reports of a pilgrim named Egeria who described the 4th century church as “the house of the prince of the apostles”, indicating that the walls of the house were left intact to better preserve the original appearance.

- A pilgrim from Piacenza who visited Capernaum around 570 wrote: «Item venimus in Capharnaum in domo beati Petri, quae est modo basilica» («We also came to Capernaum, to the house of Blessed Peter, which is now a basilica»).

- The house is particularly spacious. This seems to agree, according to Franciscan archaeologists, with the Gospel indications that Simon Peter lived with the family of his brother Andrew and with the family of his mother-in-law (Mt 8:14-15, Mc 1:29-31, Lc 4:38-39).

However, I think it is very difficult to decide in the affirmative on this question. As far as we know, it is quite possible that Peter died in Rome, and that his brother Andrew was also executed far from Galilee. Presumably, Peter took his wife and children with him, which leaves Peter’s house empty of occupants a few years after the Master’s death. Most likely, Peter sold his house before dedicating himself to preaching the good news throughout the world, as Jesus had asked them to do during his postmortem appearances. Furthermore, the general idea among the early Christians was that the end of time was near, that Jesus would soon return to carry out the final and definitive judgment. It became a Christian custom to sell all one’s possessions and donate the money to the community to be used in spreading the good news (see Acts 2:44-45, 4:32, 5:11).

If we read all about Peter in the Acts of the Apostles, we clearly see that Peter does not seem to have returned to Capernaum for a long and prolonged period, but for good. We see him in Jerusalem, where he does not seem to be the leader of the community, since he is sent to Samaria to confirm the new believers (Acts 8:14). We then see him in the pagan capital of Samaria, Caesarea, where he initially had reservations about mixing with the Gentiles. Finally, he had to return to Jerusalem to give an explanation for his preaching among foreign peoples.

For those of us who read The Urantia Book with any credibility, there are many other possibilities for the ownership of the house-church in Capernaum. These are the ones I have found:

- Philip’s House: The apostle was a native of Bethsaida and lived with his family in Bethsaida (UB 139:5.1). Although Bethsaida has traditionally been placed on the other side of the Sea of Galilee, The Urantia Book offers a quite different view of where this mysterious town was located, and I hope to be able to offer an article with my conclusions.

- The House of Zebedee: The father of the apostles James and John lived in a large, spacious house on the beach with his wife, his son John, and his daughters (UB 129:1.4). This was the house in which Jesus lived during his time in Capernaum. But this house was not in Capernaum, but on the outskirts near Bethsaida. The fact that this house was on the outskirts, in the open country, was due to the fact that Zebedee’s extensive shipyards were nearby. This makes more sense what is told in The Urantia Book about a tent camp where the many believers who came to hear Jesus gathered (UB 148:0.1).

- The house of James Zebedee: was also located on the outskirts of Capernaum, near his parents’ home (UB 139:3.1).

- David Zebedee’s house: it seems that he had his own house located also on the outskirts of Capernaum, near that of his parents (UB 138:5.4).

- Peter’s house: The apostle and his family lived with his brother Andrew, who was a bachelor, and his mother-in-law (UB 139:2.1). Peter’s house is said to have been near that of Zebedee (UB 145:2.15), so it was probably in Capernaum, but in the southwest part of the city.

- Matthew’s house: although the apostle had his workplace in the customs house, we are clearly told, even in the gospels, that Matthew invited Jesus to his house, which was most likely in Capernaum. In addition, the lucrative work of a publican would surely allow Matthew to have a good house in the small town (UB 139:7.1, UB 138:3.1-4).

- The house owned by Jesus where his mother, the family of his brother James, and his sister Ruth lived: this house is mentioned to us as a modest “little house” with only two rooms, that is, two bedrooms that probably shared a common courtyard (UB 129:2.4).

- The house of the Roman centurion, Mangus: a house which Jesus ultimately did not enter, admiring the man’s great faith: “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof. But only say the word and he will be healed” (UB 147:1.1-4). He must have been quite a wealthy person to make the donation for the construction of the synagogue. It is not unreasonable to think that his house was large, spacious, and was located in a place not far from the synagogue that he promoted.

- The house of Jairus, one of the rulers of the synagogue: Jesus supposedly heals the daughter of this wealthy man from Capernaum, who thereafter becomes a believer (UB 152:1.1-2 and UB 154:1.2).

If we assume the correct location of Capernaum, and that the synagogue now visible, dating from the fifth century, is built on the foundations of the one sponsored by the Roman centurion, then all the houses mentioned in The Urantia Book as being located outside Capernaum or in Bethsaida must be ruled out. This excludes the house of Philip, that of Zebedee, that of his sons James and David, and that of Peter. Therefore, according to The Urantia Book, the basilica-church built in Capernaum was not on the site of Simon Peter’s former home. Most likely, the early pilgrims spread this idea in order to give the site a more sacred significance. In fact, at the time when we have references to the pilgrims, Peter was already called the “prince of the apostles.” How could the basilica be built on top of a house other than that of such a distinguished apostle?

But in my opinion, that was the case. The dimensions of the house on which the octagonal church is located are large enough for a family of modest fishermen. On the other hand, we have already seen that the evangelical evidence never places Peter in Capernaum again. Most likely the apostle never set foot in his old city again, selling his property and following Paul to Rome, where he died. I very much doubt that four hundred years later Christian believers of that generation would remember where Peter’s house was and would build a simple basilica there, and later a church.

My idea, which may be totally far-fetched of course, is that the house on which the church sits was once owned by Matthew, or by Jairus, or was the house of Mangus, or was simply the house of an unknown Jew whose descendants eventually sold it to devout Christian Jews and built a church. But I find it unlikely that it was really Peter’s. I might not object if the house were smaller and located further away from the synagogue.

Matthew, the publican apostle, disappears from the map in the Acts of the Apostles. We have no news of him anywhere. But if he really was the one who wrote the gospel that bears his name, and he wrote it in Aramaic, as the experts say, it is quite possible that he stayed for some time in a quiet place far from intrigues where he could devote himself to writing. Matthew could therefore have been one of the apostles who stayed for some time in Capernaum. His comfortable position makes him ideal for having a large house, and for holding banquets there such as the one he offered to Jesus according to the gospels. However, if we are to go by The Urantia Book, we are told that Matthew ended up in poverty and that he went to preach in Thrace, where he died. If this account is true, Matthew’s house becomes a somewhat unlikely place.

Jairus, the wealthy synagogue leader whose daughter Jesus supposedly rescued from death, and who undoubtedly became a follower of Jesus, is a strong candidate. The fact that he was wealthy fits very well with the dimensions of the house found below and the fact that the walls were plastered and re-plastered several times over the years. Plastering was only done by wealthy families. The house of a simple fisherman would have been made of exposed stone with brushstrokes of mortar filling the cavities. On the other hand, it is logical to think that the house of the former synagogue leader was located close to the synagogue, as is the case (the synagogue and the remains of the church are opposite each other). Furthermore, Jairus, being wealthy and holding a position of responsibility among the Jews, is less logical to think that he would give up all his possessions and leave Capernaum with his family.

Mangus, the Roman centurion, might be another possible candidate. He was obviously wealthy. His generous donations to the building of the synagogue prove this. He must also have been a convinced believer. Even Jesus said of him: “I have not found such great faith in all Israel.” He was quite possibly a beloved person, even though he was a Roman. He must have been a Roman who became a Jew, a “proselyte.” His family must have lived there forever, and after generations they would have been considered as Jewish as any other. Moreover, the simple basilica built during the 4th century must have been the work of Jews with Gentile influence. Basilicas were typical Roman buildings, but not Jewish.

Finally, another logical option is that of an unknown Jew who was never heard of in the pages of history. Why not?

If we think about it, it was much less attractive for the “tourists” of the Byzantine era to say that the famous basilica of Capernaum rested on the remains of a house of just anyone, compared to how different it sounded to say that it was the house of Peter. The interest in that it was Peter’s house did not lie in the apostle, but in the fact that it has always been assumed that Jesus lived in Peter’s house while he was in Capernaum. This made the church the place where Jesus himself lived. However, the gospels never clearly express this idea, only that Jesus was in that house on several occasions.

Obviously, what pilgrims have always sought is to sacralize a place, to make it special by claiming that “someone distinguished” lived, died or was buried there. And they have not hesitated to use a place and base it on the most remote justifications to reach the desired conclusion. I am inclined to think that this is what happened in Capernaum.

Theories aside, I think it is very difficult to come to a firm decision on a solution. But what I do know is that archaeology is too often used for “tourist” and “religious” purposes, quickly choosing a possibility when it is of interest. Just look at how money has been spent to build a beautiful modern church in Capernaum on the ruins of the old octagonal one, while the same is not done to continue digging up the site. Sometimes archaeology seems more like an end in itself (reaching a preconceived conclusion) than a means to develop “possibilities.” And in the end, what happens is that we are no closer to the truth.

And before I finish, I’ll leave you with an interesting anecdote for readers of The Urantia Book. Has anyone noticed that the octagonal church has a floor plan that is actually three concentric circles? Was this symbolism already present in some way in the iconography of the early Christian community? If so, it is a very interesting fact, which will be worth investigating…

¶ External links

¶ References

-

John D. Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, Jesús desenterrado (Excavating Jesus), Editorial Crítica, 2001.

-

Archaeological sites of Capernaum. (The original link is broken but a copy can be accessed at Internet Archive.)