© 2005 Jan Herca (licence Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

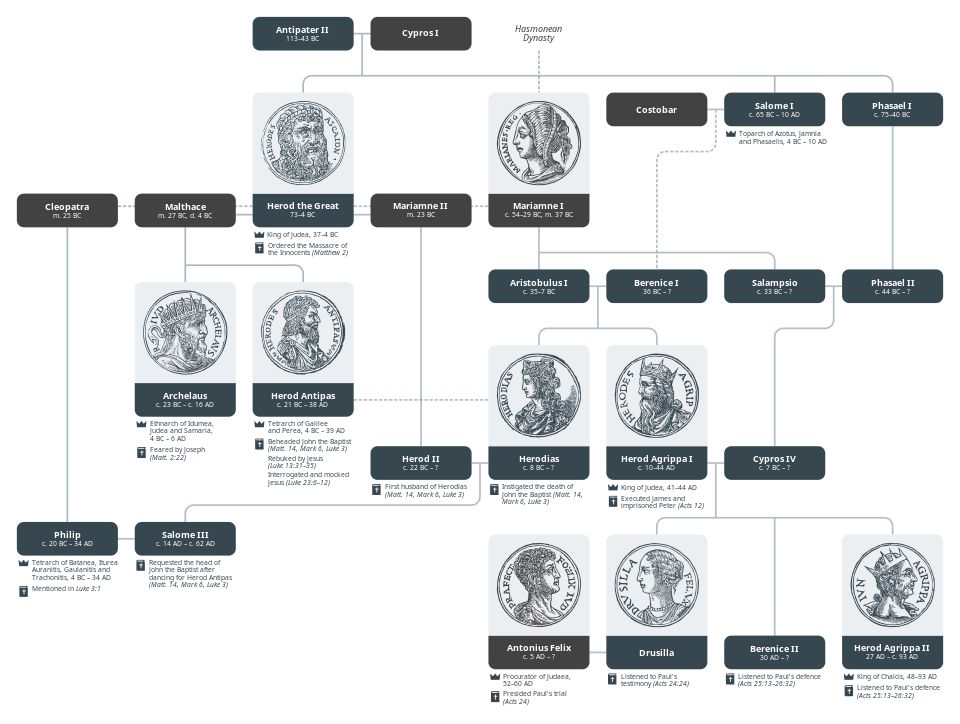

During the time of Jesus there were two royal dynasties, the Hasmonean (or Maccabean) and the Idumean (or Herodian), who lived in constant discord and confrontation. The Jews always considered the first to be the legitimate lineage to sit on the Jewish throne, while the second, imposed by Rome and originating from a kingdom, Idumea, south of Judea, was always under permanent rejection. Furthermore, these Idumean kings were more influenced by Hellenistic ideas and introduced many customs that provoked the anger of their subjects.

Jesus’ life coincided with two generations of Idumean kings. On the part of the Hasmonean lineage, they had been deposed, although not exterminated. On the Idumean side, the reign of Herod the Great, or Herod I, lasted until 4 BC; and from then until the end of Jesus’ life, the reign, or rather, the government, of some of the sons of Herod I. Each of them took charge of some regions within the kingdom: Herod Archelaus was ethnarch of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea; Herod Antipas was tetrarch of Galilee and Perea; and Herod Philip was tetrarch of Gaulanitide, Trachonitis, Auranitide, Batanea, Panias, and Iturea.

¶ The court officials

Herod the Great and later his sons provided themselves with a large troop of servants, officials and guards to attend to all their luxurious needs and safeguard their personal integrity, which was in constant danger because they were imposed kings and considered to be of illegitimate lineage.

Following the investigations of Joachim Jeremiah, we can list these court servants in the order of their appearance if we were to imagine ourselves entering the palace of one of these ancient monarchs.

First, we would encounter the royal guard. It must have been very numerous, because Herod is said to have sent 500 men of this guard to assist the Emperor Augustus, which means that he probably had at least 10 times as many men and that this detachment did not represent a great decrease in his ranks (AJ XV:9.3). On the other hand, it is not possible to think that there were only Jewish soldiers in this guard (AJ XVI:7.1, AJ XVII:7.1), because they would not have been very reliable for these Idumean kings. From Josephus we know that the guard also consisted of Thracian, Germanic, and Gallic troops (AJ XVII:8.3, BJ I:33.9). The Gauls, in particular, had previously been in the service of Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, and numbered four hundred men (BJ I:20.3). These troops may well have caused fear among the Jews, as these men were unfamiliar with them. It may have been a detachment of these men who went to arrest John the Baptist, sent by Herod’s son, Antipas. Along with these troops were the most sinister of the servants, the executioners, who were busy during the time of the Idumean monarchs.

Immediately afterward, we would meet the porters, who were in charge of leading the newcomers (AJ XVII:5.2). Josephus speaks of five hundred servants at the court of Herod I (AJ XVII:8.3, BJ I:33.9), most of them slaves, but also freedmen and eunuchs (BJ I:25.6, AJ XVII:2.4, the latter being castrated men who took care of the women in the harem). Among these servants we find the heads of the chambers (each royal chamber probably had those responsible for ensuring that everything was in order), the royal hunters, under the orders of a chief hunter (AJ XVI:10.3), the court barbers (BJ I:27.5-6, AJ XVI:11.6-7), the court physicians (AJ XV:7.7, AJ XVII:6.5), and every imaginable kind of servant, such as a braider of royal crowns mentioned in the Talmud. Luxury and ornamentation were beyond measure in these princely courts, exceeding the wealthy class in every way possible to display superiority and royal dignity.

Had we been allowed entry, perhaps thanks to a safe conduct pass, we would have been made to wait in the chambers where the royal officials waited. Among these we find the royal secretary, through whose hands all the correspondence passed (AJ XVI:10.4, BJ I:26.3). We also have the treasurer, a figure of fundamental importance and whose name we know from the time of Herod I, called Joseph (AJ XV:6.5). He was famous for acquiring a pearl of extraordinary value for the royal treasury, a story that surely inspired the parable of Jesus recorded by the evangelist Matthew (Mt 13 45-46).

Among the king’s or ethnarch’s closest attendants are the princes’ tutors, who also provide conversation and entertainment for the monarchy. They were often Hellenistic in nature. Two of them are mentioned by name at the court of Herod I: Andromachus and Gemellus (AJ XVI:8.3-4). The sons of these tutors and members of the nobility were often “foster brothers of future kings” (paides basilikoi), and were given special status when their adoptive brothers ascended the throne (syntrophos). Specifically, a syntrophos of Herod Antipas is mentioned in Acts 13:1, named Manaen, who was a Christian teacher who lived in Antioch. This character, along with a certain Chuza or Cusa, administrator of Herod Antipas (Luke 8:3, LU 150:1.1, LU 154:0.2), husband of Joanna, one of Jesus’ followers, are two clear examples that there were already followers of Jesus in Herod’s court.

But perhaps the closest of the king’s advisors was the so-called somatophylax, or officer of the royal chamber, who in the case of Herod I was an Arab syntrophos named Corinth (BJ I:29.3). Three very influential officials are also named, and given seemingly secondary positions: the cupbearer, the carver, and the chamberlain (AJ XVI:8.1, BJ I:24.7). However, in ancient royal courts, these positions designated very distinguished figures. The cupbearer, who had the sole privilege of serving the king’s cup; the carver, who in turn had the privilege of cutting and serving the food; and the chamberlain (who comes from the chamberlain), who was in charge of all matters of the royal chamber. The latter is even said to have managed many of the king’s business.

¶ Royal Relatives

Once we were given the go-ahead and free to move around the palace, we would meet the king and queen (in the case of Herod Antipas, he did not have royal dignity, but rather his position was that of tetrarch), and their close relatives and closest friends in their chambers. We have sufficient evidence of Herod I with Nicholas of Damascus, a wise and cultured man, philosopher and court historian, and his brother Ptolemy (AJ XVII:9.4, BJ II:2.3), as well as another Ptolemy, minister of finance and chancellor (AJ XVI:7.2, AJ XVII:8.2), and Irenaeus, Greek teacher of rhetoric (AJ XVII:9.4, BJ II:2.3).

Besides these regular inhabitants of the court, there were also frequent guests from other royal houses or high-ranking officials of the Roman Empire, such as Marcus Agrippa, son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus; Archelaus, king of Cappadocia; Eurycles of Sparta; Evaratus of Cos; and Melas of Cappadocia.

¶ Troop Leaders

The troop of soldiers was led by a commander. At the court of Herod I we find a certain Volomnius, a field commander (perhaps a Roman), who, together with Caesar’s friend Olympo, was sent with an escort to Rome (AJ XVI:10.9).

¶ The Harem

Jewish kings, like all Eastern courts, viewed polygamy among the common people very poorly, but they openly permitted it among royalty. It was another sign of their status. The Mishnah grants the king up to 18 wives, but the Talmud, in keeping with older teachings, extended that number to 48. Thus it was not uncommon to find concubines at the Hasmonean or Herodian courts. Herod the Great had ten wives (AJ XVII:1.3, BJ I:28.4), and he had at least nine of them at any one time. Although it seems that only the Hasmonean Mariamme had the official title of queen (BJ I:24.6). It is certain that along with these ten wives, Herod had more in his harem. The king’s mother and her sisters also lived in the palace in the harem. When young, sons and daughters also lived in the harem, under the care of their mothers.

This sector of the court had a large staff of slaves and eunuchs who served the women in their needs.

¶ The Minor Courts

Princes, when they reached adulthood, could enjoy their own courts, within the same palace, but attached to it. For example, we hear of the courts of Alexander, Aristobulus, and Antipater, sons of Herod I (AJ XVI:4.4); and also of Pheroras, brother of Herod I (BJ I:23.5).

¶ References

- Joaquín Jeremías, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1977, pp. 105-110.