© 2009 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

Nazareth is a must-see stop on any route related to the life of Jesus. It appears many times in the Gospels (although never in the Old Testament), mentioned as the city where Jesus lived as a young man.

There is a need to find information that can give us an idea of what this town was like, where Jesus lived for so many years. I will follow the narrative provided by The Urantia Book to be able to outline some general lines of knowledge about what the city could have been like. I will also use the narrative given by journalist JJ Benítez in his best-seller Caballo de Troya 4 y 5. Finally, we will compare this information with the data provided by modern archaeology about the city.

¶ Nazareth according to The Urantia Book

We find the details about the location of Nazareth and Jesus’ home in UB 122:6 (“Birth and Infancy of Jesus,” section 6, “The Home at Nazareth”).

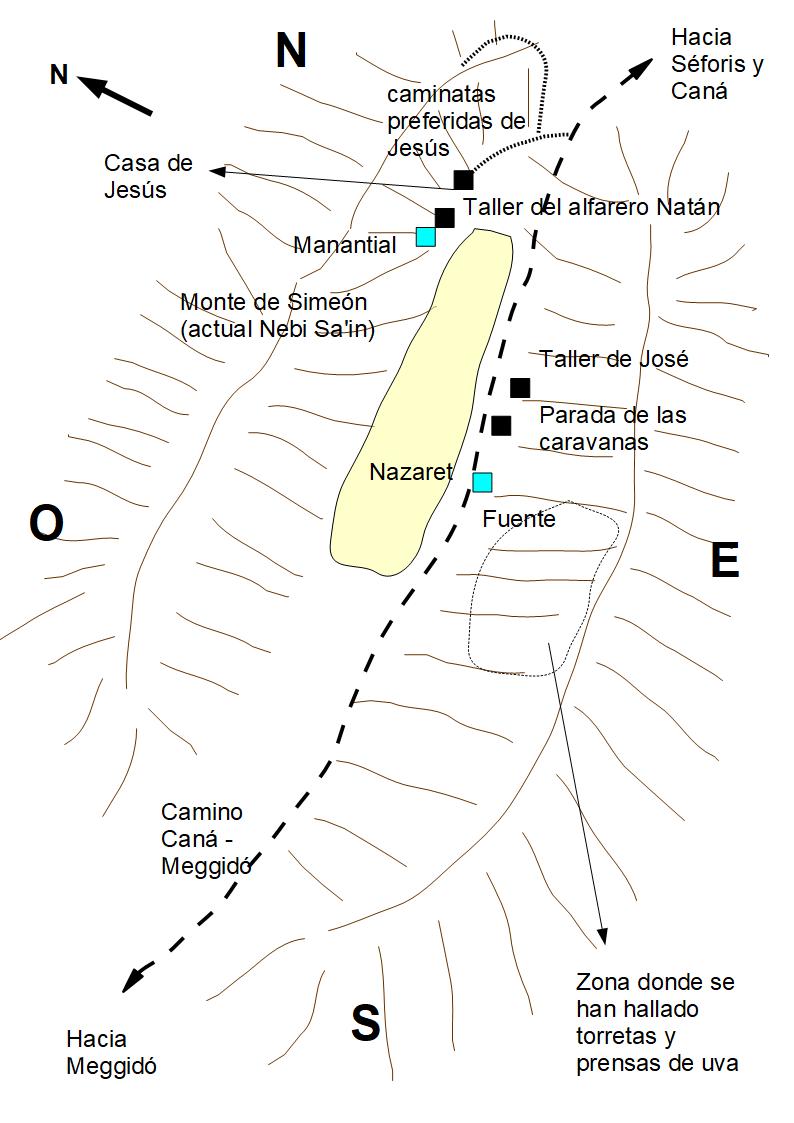

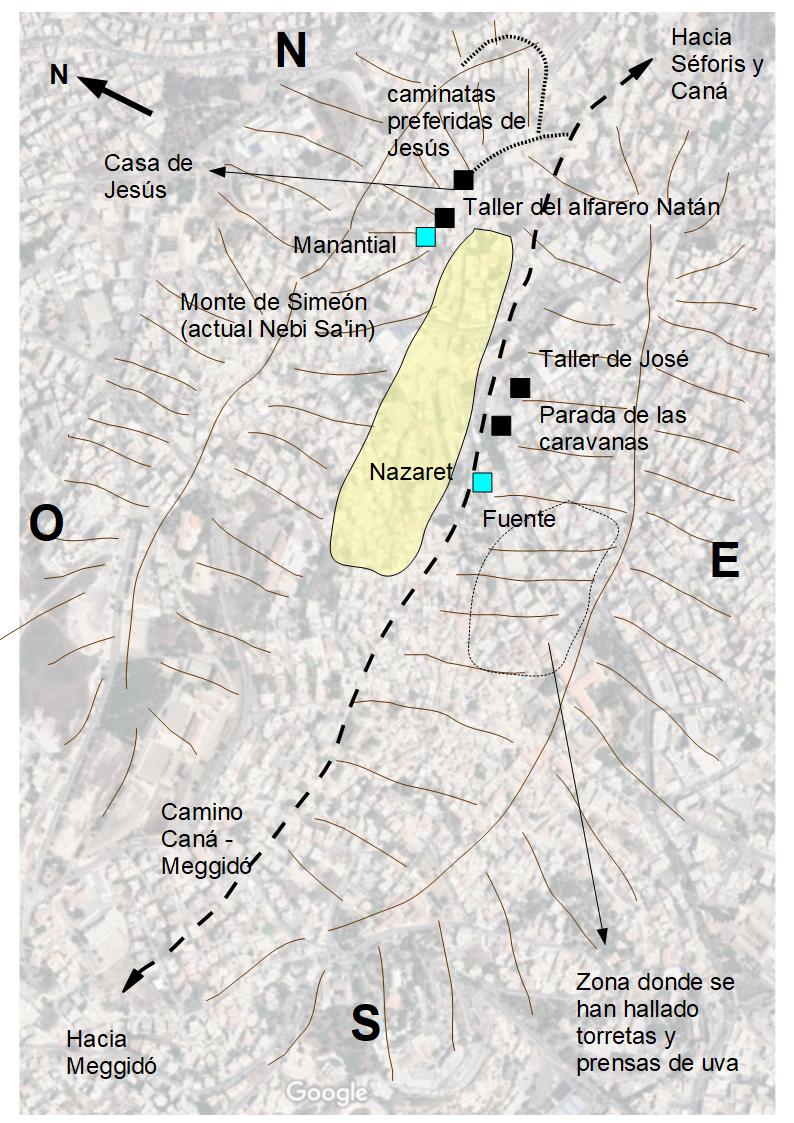

We are told that Nazareth was located in a valley between high hills. The valley followed the current main direction of the city, from the northeast to the southwest. Following this direction, but on the eastern bank, ran the road from Capernaum - Cana - Sepphoris - Nazareth - Meggido. This road, the “road of the sea” or via Maris, was a very frequent route for caravans crossing Galilee in a south and north direction. On this road, near Nazareth, there was an important caravan stop, which made Nazareth a privileged place of passage for foreign people and goods.

The hill range to the northwest is mentioned in UB 126:1. It describes the spectacular views enjoyed by young Jesus on his frequent hikes to the summit. The Urantia Book says that this hill was once a place of Baal worship, and that it contained the tomb of a prominent Jew named Simeon. Curiously, the present name is Nebi Sa’in (nebi apparently means prophet). Perhaps an ancient prophet named Simeon? There is no record of that. Nor have I been able to confirm the discovery of a tomb on this hill in Nazareth.

As you can see, the Nazareth depicted in The Urantia Book is an elongated city, following the direction of the valley. It places Jesus’ house not in the city, but in the northern part, on the outskirts.

The Urantia Book calls it a “city” rather than a village or hamlet (as JJ Benitez does). In fact, there is a strong discrepancy between the view given by The Urantia Book and JJ Benitez’s novels about the size and importance of this town in Jesus’ time. According to The Urantia Book, in Paper 124, “Galilee . . . was a province of agricultural villages and thriving industrial cities, containing more than two hundred towns of over five thousand population and thirty of over fifteen thousand” (UB 124:2.9). It is obvious to think, given Nazareth’s strategic location, that it would be among those 200 cities. It is therefore not possible to estimate the population of Nazareth at 300 to 350 inhabitants, as J.J. Benítez does in Caballo de Troya 4, page 164. The author is probably guided by the conclusions of modern archaeology, which has not found evidence of a large city in Nazareth.

At that time, we cannot forget, Cana, very close to Jesus’ village, held the rank and status of a “notable city”, considerably more populous, rich and “civilized” than that lost handful of houses, crouched on a no less remote hill. If the inhabitants of Cana could be counted in the thousands, those of Nazareth, on the other hand, numbered barely fifty families, with an approximate contingent of three hundred to three hundred and fifty souls. That was all. In this setting - with its advantages and disadvantages - the Son of Man grew up and came to life. At the end of his misnamed “hidden life”, the disadvantages eclipsed the advantages and, as was pointed out, Jesus found himself in the need to distance himself from that endearing and difficult human group.

Caballo de Troya 4, J.J. Benítez, p. 164.

If we follow the narrative of The Urantia Book, we get a view of Nazareth that breaks somewhat with the vision that archaeology has been able to reveal. Nazareth is depicted as a large town, with a good number of inhabitants, probably between 5,000 and 10,000 inhabitants. A not insignificant number. This figure makes the expression “on the outskirts” more meaningful as a description of the location of Jesus’ house. If Nazareth had been a small village of barely thirty houses with very few inhabitants, it is not understandable that it was a common place for caravans to stop and repair, or that Joseph would have built his house far from the “urban” center. The general description in The Urantia Book tells us more of a small city than a village, with its own synagogue (not a house serving as a synagogue), with workshops for supplying and repairing caravans, and a caravan house that would accommodate multitudes of travelers from all over the known world with their pack animals. Jesus lives on the outskirts because the crowded “center” of the city must have been too expensive for Joseph to afford a home. In fact, toward the end of Paper 126 in The Urantia Book, we are told that Jesus “entertained the wish that they were all located on a farm out in the country where they could enjoy the liberty and freedom of an unhampered life” (UB 126:5.10). Doesn’t this feel like the typical longing for the countryside that a city dweller might have? Isn’t it a bit strange that a person living in a small village should long for the “countryside” when there is so little urban pressure around them?

Joseph’s workshop and the caravan parts stores, according to The Urantia Book, would have been located east of the road on the outskirts of the town, not far from the spring that supplied Nazareth, which is also mentioned as being located in the eastern area. We can get an idea of this area as the “industrial” part of the town, where the jobs of other craftsmen such as the blacksmith, the stonecutter, the tanner, the ropemaker, or the canvas maker would probably also have been located.

Another piece of information from The Urantia Book that gives a view of Nazareth as a “city” is that of UB 123:5.12, which states that Nazareth was one of the 24 priestly centers of the Jews, with more liberal priests than in the rest of the Jewish territory. This implies that priests lived in Nazareth, which clearly shows that Nazareth was not a small village but a relatively populated city, with wealthy families among its inhabitants.

The image below shows a diagram that places the references offered by The Urantia Book.

¶ Nazareth according to current archaeology

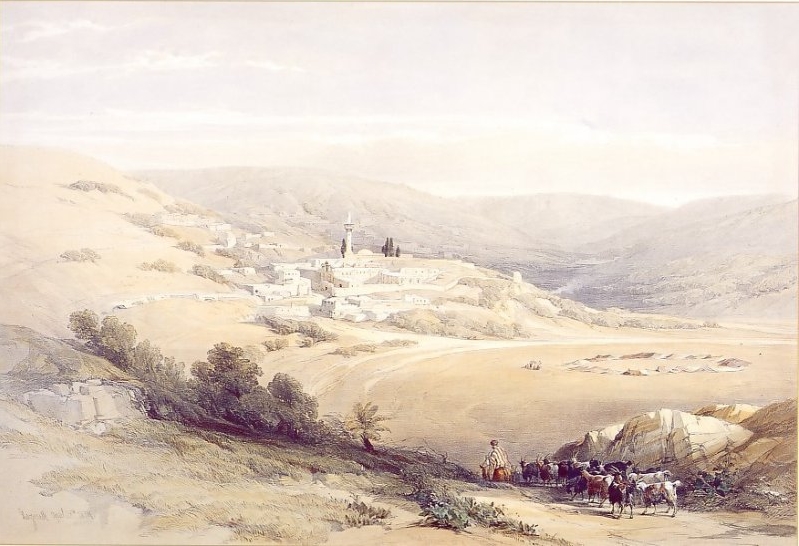

If we now turn to contemporary archaeology, the evidence points in the opposite direction. Not many remains from the time of Jesus have been found in present-day Nazareth. The city is today a populous city of more than 40,000 inhabitants, which with its growing urbanization has practically erased many of the possible vestiges of that period. Curiously, archaeology has unearthed finds from the Bronze Age, more than 5,000 years ago, which attests to the fact that Nazareth is an ancient town whose existence is lost in the past of time.

The findings reveal that there is no evidence to suggest that Nazareth had a synagogue at the time of Jesus. The remains found speak of a synagogue at a later period. No significant remains of buildings or constructions from the first century have been found either. Significant finds have only been made regarding what could be silos, warehouses, or underground mangers. Apparently, many houses in Nazareth had cellars and caverns dug into the rock where grain, wine and oil were stored, or where animals were kept.

This absence of remains leads archaeologist Jonathan L. Reed and exegete John D. Crossan, in their book Jesús desenterrado (Excavating Jesus), to propose a vision of Nazareth like that of JJ Benítez, as a small village of about two hundred inhabitants dedicated exclusively to agriculture, in a rustic environment far from the influence of the main trade routes.

One of the arguments in favour of this view is that Nazareth is not mentioned in the Old Testament, nor in rabbinical writings, nor in the books of the Jew Flavius Josephus. The latter, who acted as a military leader in Galilee during the Jewish uprising of 66-67 AD, names 45 towns in Galilee in his writings, but never Nazareth.

However, Reed and Crossan do not overlook the discovery at Caesarea Maritima in 1962 of a third- or fourth-century inscription, in which Nazareth is mentioned for the first time in a non-Christian source. This fragment and two others unearthed with it contain a list of the traditional places where Jewish priests settled after the Emperor Hadrian expelled all Jews from Jerusalem in AD 135. Of the 24 priestly families who cared for the temple in Jerusalem, the Hapizzez family, the 18th, is mentioned as having settled in Nazareth. The authors acknowledge that Nazareth must therefore have been a suitable place for priests to take refuge at that time. But how could a small village of about 200 inhabitants, so insignificant that it is not even mentioned in any source, be such a place? What kind of comforts could such a small village offer to such distinguished persons as an entire priestly family? Here the statement of The Urantia Book that Nazareth was a priestly center, and that it had a certain population, seems correct.

The authors of Excavating Jesus also admit that the absence of remains of synagogues from the first century is a common occurrence in archaeological excavations throughout Galilee and Judea. However, there are notable exceptions in some towns which were not particularly developed. The clearest example is the small town of Gamla in the Golan Heights. It has the best remains yet of a first-century synagogue, while other larger towns, of which there are remains, do not clearly show the location of a synagogue. In short, the size and importance of a town cannot be determined simply because archaeology has not found remains of a synagogue.

Does this lack of archaeological finds mean that we must conclude that synagogues in Jesus’ time were an exception? Unfortunately, that seems to be the position of scholars. If archaeological remains are not found, they did not exist. For Reed and Crossan the situation is clear: Nazareth did not have a synagogue. What then about the Gospel accounts (Lk 4:16-30, Mt 13:54, Mk 6:2), in which we are told on several occasions of a synagogue? Crossan easily resolves this: the Gospel account is a later invention of the evangelist Luke. That is to say, Jesus was never in a synagogue in Nazareth.

Luke assumes that a small village like Nazareth had its own synagogue building and its own volumes of Scripture. The first assumption is highly unlikely, and as we have already pointed out, not the slightest evidence of a first-century synagogue building has been discovered on the site.

…

… This episode is not only found in a late stratum of the tradition about Jesus, but it also derives from it. In other words, it is an episode created by the evangelist Luke himself.

Excavating Jesus, Crossan and Reed, pp. 51-52

Personally, I think that the absence of archaeological finds means nothing. It may simply be that there is no evidence at all because the passage of time has eliminated it. Where there is none, it is impossible to extract anything, no matter how good an archaeologist you are. It is the discovery of remains that reveals things to us, not the absence of them. Drawing conclusions when we have nothing to base them on is like shooting in the dark.

But among the recent archaeological finds, we find a prominent discovery: an area with turrets and grape presses that has opened up new evidence about Nazareth in the time of Jesus.

The find in question was made during a visit to the Nazareth hospital in November 1996 by Stephen Pfann. Pfann found remains of pottery from the early and late Roman period. Excavations in the area carried out in February 1997, under the patronage of the Israel Antiquities Authority, have uncovered terraced agricultural sites on the hillsides, with a grape press, watchtowers, olive-grinding stones, irrigation systems and an ancient quarry, all from the Roman period, the time of Jesus. The watchtowers and the excavated winepress have been a very curious discovery, because they give a reason for the parable of the murderous tenants (Mt 21:33), in which Jesus speaks of these towers and this type of winepress. This coincidence clearly reflects the process that Jesus followed to tell parables: he simply extracted everyday facts from his agricultural experience in the field.

The findings have given rise to an interesting project to create a unique theme park dedicated to recreating life and customs in ancient Nazareth at the time of Jesus.

All these discoveries are supposed to fill at least the void of discoveries about the time of Jesus, bringing to light valuable data about agricultural life in his time and in his surroundings, a life to which he must have been accustomed. However, these discoveries tell us nothing about religious life (whether or not there was a synagogue), or about social life (whether Nazareth was really on a caravan route and how many people it had). Reed and Crossan do not even mention the existence of this caravan route. Perhaps there is no evidence of it, but there are many ancient maps that place a frequent road in Jesus’ time passing through Nazareth. Nor do they mention anything about a priestly centre in Nazareth, although strangely, evidence has been found that places an entire priestly family in Nazareth in the 2nd century. Too few clarifications for data that I believe give more of themselves.

Despite all these discoveries, the Nazareth revealed to us by modern archaeology does not, at this time, coincide with the revelations of The Urantia Book. In light of the excavated remains, Nazareth seems to be a small town that lived in anonymity until it was rescued from oblivion by Christianity. According to The Urantia Book, Nazareth was a prosperous city located in a strategic enclave, on the caravan route, an exceptional position for a singular character like Jesus, who would be attentive to the news of the world.

¶ The importance of Nazareth in the knowledge of Jesus

Why is there so much importance to whether Nazareth had a synagogue or not, whether it was a priestly centre or not, or whether caravans from the East stopped there? How does this affect our view of Jesus?

The vision of Nazareth is important because it allows us to draw immediate conclusions about Jesus’ way of life, his personality and who he really was.

For example, Reed and Crossan end by stating in Excavating Jesus that Jesus could neither read nor write, and that he lived ignorant of the world and foreign countries.

But Luke also assumes—and this is the most important thing—that Jesus was not only a literate person, but even a cultured one. He did not simply “stand up to teach” in the synagogue (Mark 6:2), but “stood up to read” (Luke 4:16). Luke, who was a cultured man, obviously takes for granted, as do many modern scholars, that Jesus knew how to read and write and that he was a cultured man. It is highly unlikely that this was the case.

Excavating Jesus, Crossan and Reed, pp. 51

Since they depict a tiny Nazareth, far from the main routes, and since there is a void of the remains of a synagogue, they assume that the Knesset (synagogue) did not exist, and therefore there were no scriptures or scrolls with sacred texts in Nazareth, and therefore, since there were no scriptures, Jesus could not have received an education in reading and writing.

What these two scholars do not explain is how Jesus can appear in the Gospels entering synagogues, opening scrolls and beginning to read. How there is a passage in the Gospel in which Jesus begins to write in the sand in front of a woman’s accusers. Nor is it very easy to understand how Jesus began to argue with the doctors of the law when he was thirteen years old.

The importance of knowledge of Nazareth is vital, as you can see, to better understand the life of Jesus and who he was. As The Urantia Book describes Nazareth as a small town with a synagogue, and a copy of the scriptures, it is easier to understand that Jesus was raised, like many other Jews, in an urban environment, where reading and writing were part of daily necessities. It is easy to understand that he would enter the synagogues and be able to read the “Hebrew” of the scriptures without any problem and translate it into Aramaic for the audience, which was the preferred language. It is easier, in short, to understand that Jesus developed in an environment that provided him with a sufficient cultural foundation to later astonish his countrymen with his knowledge of the scriptures.

Jesus must have known priests in Nazareth, Pharisees, who were very common everywhere, and Sadducees. These groups included the wealthy stratum of the city, and they lived in the rich neighborhoods, in distinguished buildings of which, unfortunately, no remains have survived.

He must also have made contact with many foreigners from other parts of the world who offered him knowledge about the races and peoples of the Earth, and who would serve to launch his admonition to the apostles to go out and preach throughout the world, as was indeed the case.

Perhaps future discoveries will bring discoveries that will broaden our view of Nazareth. In my opinion, the current city has erased many traces of the past, but it is possible that beneath the garages of many Nazarene houses there are remains that will reveal important data one day.

¶ References

-

John D. Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, Jesús desenterrado (Excavating Jesus), Editorial Crítica, 2001.

-

J.J. Benítez, Trojan Horse 4, Editorial Planeta, 1989.

-

J.J. Benítez, Trojan Horse 5, Editorial Planeta, 1996.

-

Nazareth excavations website (the old link is broken: http://198.62.75.1/www1/ofm/san/TSnzmain.html)

-

The website where you can find detailed information about the Nazareth Theme Park project.