© 2012 John Creger

© 2012 The Urantia Book Fellowship

(Re-creation of a talk given at IC 2011)

Teenagers have no idea how obvious body posture is when we text. Even kids who promise me no teacher will ever catch them, don’t have a clue. I’m in their faces so fast, I’m so pleasant (most of the time), they usually just hand over the phones. No complaints.

But I have to eventually give those back.

If you’d like to make a more permanent contribution to public education, just strike a texting pose. Before you notice I’ve swooped down to your seat and back to the stage, your Blackberry will be in my collection.

Now, when I was in high school, the closest thing we had to a texting pose was even more obvious. The point then was to get the teacher’s attention without seeming to care. We used passive-aggressive technology from the back row.

Strikes a bored-in-back-of-the-class-with-folded-arms pose.

As you’re probably guessing, high school didn’t catch my attention very deeply, unless being disgruntled is deep. I don’t recall the thought of reporting for graduation crossing my mind as a serious option. The day after the ceremony I didn’t attend, I started my life with one plan: stay as far from classrooms as possible.

A dozen or so years later I found myself at the university. I’m doing at least one all-nighter a week, writing papers in a state of near bliss. I graduated in English with writing published in five languages on three continents. My body posture in college? Leaning forward in the front row of the lecture hall taking notes with all my might. So what made the difference? Why the folded arms in high school and the steroidal notetaking in college?

In my mid-twenties I had picked up a hitchhiker who carried large portions of The Urantia Book in his memory. Thumbs out on an onramp in Concord, New Hampshire, as I approached them on the drive home from work, he and his companion were out in the world, taking every step by the leadings they could perceive from their Thought Adjusters. The Father, it seemed, had nothing more exciting in store for them than to spend some time with me. Moving into the spare room in my cabin at the edge of the woods, my hitchhiker friend stayed for five weeks. Evenings when I came home from work, drawing on his verbatim memory of The Urantia Book in the absence of a physical copy, he devised lessons to guide me into a relationship with the Father. God was alive, a song goes, magic was afoot. Several years later I arrived at the university with a sense of purpose.

By the time I got to college, I knew the universe had plans for me. Even if I didn’t feel it continuously, or very often at all, I was convinced that I was loved by some powerful forces. Even God. I didn’t know exactly where my life was heading, but my experiences with the hitchhikers had caught my soul’s attention. The forces that had brought them to me would guide me. I was confident that the general sense of purpose I now felt would grow and, at some point, lead me to a more specific mission.

What if my soul had had a sense of purpose in high school? What if I had known then that I had a soul? How would my life be different? What if school were designed to help young people develop healthy hearts, minds, and souls filled with purpose? What if school were designed to inspire and equip students not only to make a living but to seek and find their own truths. What if schools were configured to help young people become purveyors of wisdom, passers of torches to even younger people?

So what’s this talk about?

First, this morning I want to share with you some of the uplifting things I get to see in the high school classroom. These things you’ll see and hear about, most of them created by high school sophomores, come from classroom research I run in my English classes to help young people find deeper purpose in their lives and learning. Most notably, these uplifting things come from an extended learning experience called the Personal Creed Project.

Second, I want you to see recent university research on the sense of purpose among young people today, research I think you’ll find eye-opening. I’m especially excited to share with you the latest version of the Model of Deepened Learning I have synthesized from The Urantia Book. This model, which I am currently sharing with educators across the country, is the foundation for my thinking as I attempt to develop a more workable approach to designing learning. My efforts to formulate the deepened model and workable course design, you’ll learn, are inspired by a decade and a half of consistent enthusiasm for the Personal Creed Project mentioned above. This enthusiasm comes from students in my classes at American High School in Fremont, California, students in colleagues’ classes at schools and colleges across North America, and their teachers and parents.

Finally, I want to suggest to the Urantia movement this morning the idea that learning is the central means, the core drive, of human evolution. And that since our survival depends on our ability to learn new ways of living, the greatest opportunity to uplift this world may lie in joining or supporting efforts not merely to reform but to renovate public education in this country. How’s all that sound? Bold enough?

¶ Talk of Souls in School

Re-examine all you have been told in school

or church or in any book,

and dismiss whatever insults your own soul.

These lines come from Walt Whitman’s preface to Leaves of Grass. Read them again if you like. How often today do you hear talk of souls in school?

So, how would you like to quickly scan the souls of some of my students? Yes? Did you all bring your soulscanners? Excellent. Get them out and let’s start by taking a look at two students from different sides of what’s called the achievement gap. We’ll begin with Lorato. She graduated a year ago last month and went off to a top college. Spring semester of her sophomore year in high school, she reflected for an assignment in her English class on what most mattered to her in life. Lorato chose to write about her soul:

“I think I care the most about having a ‘full soul,’ . . . I see my soul as being a mixture of several different aspects of life, including emotion, experience, wisdom, and other factors I can sense more than explain. It’s difficult to achieve, but I think once someone has one, the person gains an inner force and power that can be used to help his or her surroundings.” Lorato Anderson, class of 2010

So how typical a high school sophomore was Lorato? None too typical? Definitely not. So what was this non-typical 15 year-old kid saying about souls?

According to Lorato, our souls give us a power to benefit our surroundings. This probably includes higher purposes like benefitting others. A soul, Lorato seems to say, especially a full one, can lead us to higher purposes.

Would you call Lorato a truthseeker? So would I. Her soul was already deep when she came to me. And she was hungry to explore it. Should school support Lorato in this exploration? Agreed. Is school as it is designed today capable of helping students discover their souls or the souls of their classmates? Not yet. Motivated and resourceful, Lorato had the inner lights to continue this search on her own. Most of her classmates, however, if given the chance to think about it, would probably rate school a major distraction from the pursuit of higher purposes in general and nurturing their souls in particular.

The truth is that school is designed to abuse, even torture our souls. The twentieth century literacy pioneer James Moffett wrote that if we abused our students’ bodies as we do their hearts and minds, we’d all be in prison. Raise your hand if your soul has been insulted by your education.

Scanning the audience. Pretty well unanimous out there. Keep your soulscanners ready.

How is it that the institution that is intended to educate— to lead our souls out—instead pounds them and twists them back into the darkness? Let’s listen to Joe a minute.

Joe did virtually no work in class all year. He did every assignment, however, for a semester-long journey of self-discovery, the Personal Creed Project, which we’ll look at in a few minutes. Even with no hope of passing the class, Joe gave the Creed Project his best effort. Why? In his course evaluation, he wrote:

“The creed project has helped me find out things about myself that I would have never known before. At first I thought that this project was going to be the same stupid work that had to do with learning and school, but after I started getting into it I was so infatuated with this creed project. This project allowed me to experience deeper thoughts and explorations of my mind and soul. I found out things about my family and friends that all of a sudden appeared in my head . . . This project was tough at times to understand but paid off in the end .” Joe Deanda, class of 2005

With his dim view of school as a whole intact, Joe went proudly on to continuation school the following year. So why would a confirmed failing student write a glowing endorsement of a school learning experience? Why would he rave about being “infatuated with this creed project” which gave him “deeper thoughts and explorations of my mind and soul”? Until I read this—late in the spring—I’d seen so little work from him that I assumed he must be just another marginal illiterate. But suddenly I saw that not only did Joe command a decent vocabulary and sentence structure but could think lucidly on an abstract topic like souls. (By the way, neither I nor the written Creed project instructions ask students specifically to write about their souls. Joe and Lorato, like others over the years, chose this topic on their own.) Joe is just one of a growing list of failing and otherwise disengaged students who every year become this project’s most impassioned advocates. Ready for your next soul to scan?

Several months after her suicide plans had been intercepted and their implementation prevented, Sharla reflected in a class journal entry on the Creed presentations, the classroom rite of passage that culminates the Personal Creed Project:

“. . . the most important thing that was accomplished during this creed is finding and expressing myself. Overall, it gave me a chance to explain myself and allow people to learn and understand my past actions and behavior. And . . . it worked both ways; I discovered and understood other people’s past and influences. I even discovered that other people went through similar experiences [as] me and maybe, just maybe, in the future, we, due to our experiences, can become close, and help each other go through them, even if the problem doesn’t really exist today.” Sharla, class of 2011

Sharla (one of two such cases that year) does not directly mention her soul. But she does refer to a deeper kind of learning—and a deeper kind of relationship with classmates— than is customary in school. I received letters from the parents of both my students who had had difficulty with suicidal impulses that year, saying that they were grateful their children had been given the time to reflect on their lives, an opportunity that may have helped them survive a difficult year. My research over ten years documents my observations that the deeper kind of learning the Personal Creed Project offers students regularly engages the troubled, disrespectful, disrespected, shy, failing, and otherwise disengaged on both sides of the achievement gap. More about this project shortly.

First, what makes Joe call learning and schoolwork stupid? Is he simply too lazy to “do the work”? Or is he taking a page from Whitman, righteously dismissing work that insults his soul?

¶ The Millennial Generation and the Deathly Shallows

Most debates about school today revolve around the processes we use to deliver learning to students—how we distribute facilities, time, material and, most contentiously, money. Arguments rage about how we prepare and support teachers, about who should develop curriculum, what it should exclude, how teachers deliver instruction. They focus on how we assess the results of student learning—these days mainly through testing.

While these conversations about reforming education are important and necessary, they sidestep long overdue rethinking we need to do at a deeper level. It is time for us to look more fully into the nature, not merely the processes, of learning. The first steps to accomplish this, I think, include three things: 1) develop a deeper understanding of what learning most essentially involves; 2) design an assessment of students’ learning to determine how we currently succeed and how we fail to help them realize this deeper understanding in their learning; 3) determine what new areas we need to address in service of a deeper learning, and how best to do so. I have been working on the first of these steps.

Over more than twenty years, I have observed several thousand high school sophomores from both sides of the achievement gap, from brilliantly achieving top students like Lorato to thoroughly disengaged continuation school candidates like Joe, and all points between. I have watched them incorporate deeper learning into the processes of developing academic skills. The vast majority light up with unprecedented enthusiasm to the opportunity. It is time to go beyond shallow reform, to renovate our understanding and rejuvenate our students’ experience of learning. But our debate still centers on the surface processes of learning and avoids re-considering its deeper roots. Here is the crux of the problem as I see it: the pain and tedium school inflicts on most of us, the “same stupid work” Joe complained of, spring at the root from our dangerously shallow notion of learning.

Is it just me, or is curriculum one of the ugliest-sounding words around? One of the Latin meanings of the word, by the way, is “chariot race.” Think of the amazing journey our young people could take through their twenty-first century educations—all the non-linear, multi-dimensional, timespaceindependent, interconnected learning experiences that will become available to them as this century unfolds. How many of these adjectives remotely fit a chariot race? I wonder if our inherited notion of what curriculum should be, a line of chariots narrowing in on a finish line, each straining to arrive before the others or demolish them in the effort, is driving our students, and our culture, into a ditch.

But really, the problem is not so much that school continues to offer learning that is too linear, too one-dimensional, too school-site-centered, and too disconnected. Thanks to technology, these facets of the processes of learning are all changing, some rapidly. The deeper problem is that despite these changes school still strikes too many students as the same stupid work because our prevailing conception of learning traps students mostly on the surface of learning— primarily in what I call the mastering facts region of the model you’ll see shortly.

Learning in school as we know it fails by design even to recognize, let alone to honor, our students’ deeper parts. For Joe and for many students today, as me for and my friends in the back row a generation ago, to fight the soullessness of school learning becomes an act of honor. Though they may not have words to identify it, disengaged students, perhaps because they are least served and therefore least hamstrung by its shortcomings, can often see more clearly than others the enormous flaw in the design. Over the years, a number of these disengaged students have become my thinking partners.

One of my favorite thinking partners, Duron Aldredge, gave me permission to include in my first book his elegant graphic insight into the industrial origin of this flaw:

“Mr. Creger, I hope you don’t mind me saying this, but you know the General Motors plant in south Fremont? Well, at one end of the plant they put a chassis on the assembly line. It moves along the line, and the doors, the fenders, bumpers, seats, dash, engine and transmission get bolted or welded on. At the other end of the plant, the car comes off the line, and a printout listing everything that’s been attached gets taped to the windshield.” With his forefinger, Duron outlines an empty rectangle where this paper would sit on my windshield. “Well, Mr. Creger . . .” I see a tired patience in his eyes as he concludes: “that printout’s pretty much the same thing as our transcripts when we graduate.” Duron Aldredge, class of 2003

What is it about a chariot race or an assembly line—or a corporation—that insults the soul? School as most of us know it disregards the parts that make us unique—not only our souls, but our hearts, our creativity, and the gifts from the Father—our personalities. It ignores the parts that connect us at the deepest level—the fragments of God within us. These are the parts that inspire learning for its own sake—the parts we need to engage if we want to deepen spiritually and expand cosmically as individuals and as a culture. Learning that honors these deeper parts attracts all students. Okay. Soulscanners at the ready please.

I like how David put it. A few weeks after, in a stroke of luck, he had sidestepped being expelled because the gang fight in the school parking lot he had helped plan was discovered and aborted, this Asian-American gang member volunteered the following:

“This project gave students new avenues of thought which would help them to ascribe a better future to themselves. One can compare the Creed Project to a light emerging forth from one’s head, and awakening a person from a coma.” David Luong, class of 2004

Cultural forces in his life may have driven David toward the gang lifestyle, but deeper forces in him only awaited kindling to catch his attention in a dramatic way.

In my first book I develop the idea that learning is the core drive of evolution. The Personal Creed Project has shown me how failing students like Joe come to participate willingly in their own evolutions when guided into learning that helps them increasingly understand themselves—who they are, what they stand for, and what they want to accomplish in life—as they make progress learning academic skills and content. The project serves as a window to a new way of seeing learning, and continues to lead me to new ways to design my courses. In recent years, I have developed a number of design principles, each with a series of practices, to help students deepen their learning in sophomore English. Sometimes the combination seems to work well for students. Here’s what Judith wrote about her experience with the course as a whole:

“I started as a passive sophomore who always did what was said to do. I never went outside the box. Yet, as the year went on I felt I began to lose dependency on being “educated” by someone else. I began to educate myself of things that weren’t taught in books. I began to feel myself grow not physically but mentally and spiritually. . . . I am satisfied now because through this class I no longer have a spirit that is solely based on religion. Likewise I no longer have the mentality of only learning things from books.” Judith Acosta, class of 2006

Judith had come from a traditional learning environment in Mexico, and so this kind of independence in her learning could have been a big shift for her.

Before we get too warm and fuzzy, let’s do a reality check. What portion of our students in particular and young people in general devote much time to the kind of introspection we see in these statements from Lorato, Joe, Sharla, Duron, David, and Judith?

¶ The Reality of Purposelessness

According to recent research by a team led by William Damon, director of the Center for Adolescence at Stanford University, presented in The Path to Purpose: Helping Our Children Find Their Calling in Life (2008):

-

Only 20% of young people today between the ages of 12 and 22 has any appreciable sense of purpose or calling in life.

-

Another 25% are seriously disengaged, some actively involved in destructive behavior and lifestyles.

-

The remaining 55% of young people today, more than half, are what Damon’s research describes as dreaming with the other half dabbling.

Do these numbers ring true to you? They made sense to my sophomores when I ran these findings past them last year.

When a trusted researcher like William Damon has clearly identified a problem like widespread purposelessness among the young, and last summer’s riots in the UK have shown what happens when inequalities of class and opportunity meet this vacuum of purpose, we’d hope schools would come to the rescue. But, laboring under a sorrowfully inadequate conception of learning, school can’t even rescue this generations’ souls from the beating it gives them with its own curriculum.

You’ve heard me say that our current education system abuses us on many levels, that to one degree or another, most of us are victims of shallow learning (why am I suddenly thinking of offshore drilling?). Shallow learning leaves our deeper parts—our souls, hearts, values, purpose, and creativity—high and dry. Doesn’t this make you a little angry? And righteously so. I think this is among the deeper reasons many students are angry in school. School is about our shallow selves; our deeper selves are irrelevant to the process.

What needs to happen? It’s not complicated.

We need to think about learning in a deeper way.

Okay. You can put down your soulscanners till the end of today’s lesson. Here comes the theory part.

¶ Learning for Soul and Purpose

In the paper “The Development of the State” we find one of several statements in The Urantia Book on the purpose of education:

_The purpose of education should be acquirement of skill, pursuit of wisdom, realization of selfhood, and attainment of spiritual values. _

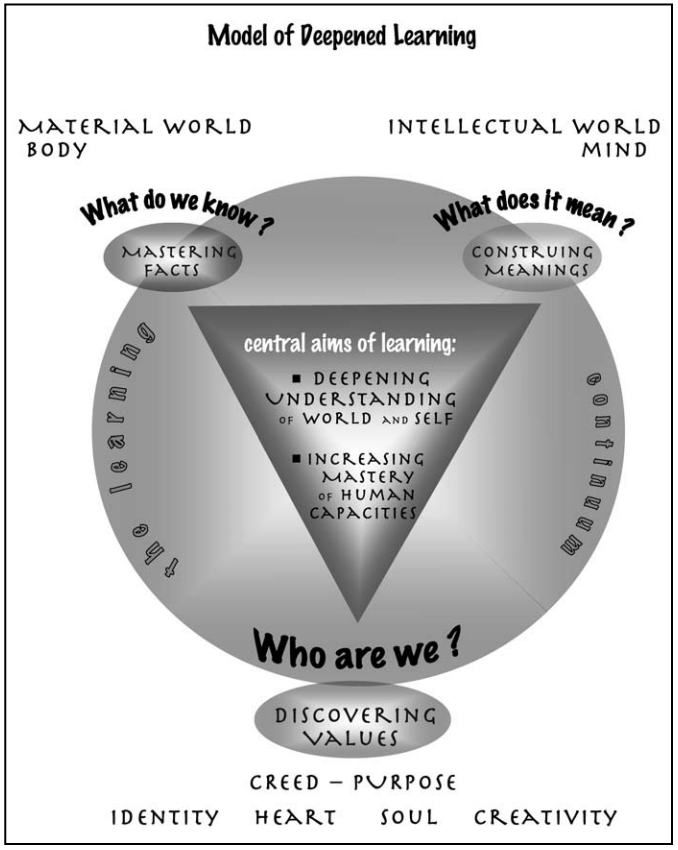

From this and other concepts and passages in The Urantia Book and elsewhere, I’ve cobbled together what I am calling the Model of Deepened Learning, see figure below.

The model is designed to serve as a guide for educators to carry forward and develop all the parts of the stated purpose above, with special attention to the wisdom, selfhood, and spiritual values parts. This Model of Deepened Learning provides a rationale for educators to develop robust and effective learning for classrooms, schools and colleges, to honor and develop students’ deeper parts in combination with what we now call academics. Clustered around a Central Aim of Learning is the crux of the model: the Learning Continuum.

We learn in The Urantia Book that as mortals we experience reality on three levels: facts, meanings, and values. The Model of Deepened Learning simply applies this awareness to learning. If we want to give students a fuller experience of learning, our plans for student learning should be balanced around three “regions” which, together, I suggest we call the Learning Continuum. Learning should be designed so students continually expand their capacity to master facts, construe meanings, and discover values. You can see this in the model. When I give them a few minutes to contemplate this model in the classroom, my students see right away that most of the learning they currently do in school, as for most students everywhere, takes place in the Mastering Facts and, to a lesser degree, the Construing Meanings regions of the model. Occasionally, some students in some places find themselves in a class or school which genuinely helps them develop themselves in the deeper Discovering Values region of the model. Rarely do schools, even more rarely public schools, have systematic plans to help students develop in this region.

This deeper learning helps students experience and appreciate the uniqueness of their personalities and those of their classmates, helps them learn how to live from the heart, develop their souls in creative endeavors. At the center of this region, deeper learning helps them discover their values-—what they stand for—and prepare themselves to find purpose in their lives. This is what the Personal Creed Project seems to do so well. What then is the Creed Project?

The Personal Creed Project is an extended, multi-layered learning experience consisting of two parts: a series of weekly reflections and a presentation. Students in my classroom undertake 16 weekly reflections culminating in two weeks of presentations. During the weeks of reflections, students send a wide, systematic net spiraling into their life experience to date (See figure, below.) After hauling in the long weeks of reflection after repeatedly sifting through and reflecting on their findings, they come to the two weeks of presentations. Once I make the first presentation, each student stands before classmates and teacher and shares these four elements:

-

these are the main forces and people that have shaped me

-

this, to the best of my understanding, is what I stand for or most value in my life [or: this, as far as I can see now, is my purpose for living]

-

these are the qualities I wish to develop in myself over the next 10 years, and

-

this is how I would like to be serving or helping others at the end of this period.

PERSONAL CREED PROJECT CONTENTS

- Step I: Influences that Shape me

7 weekly installments- Step II: Most and LEast Valued Influences

3 weekly installments- Step III: What I Stand For / My Draft Creed Statement

3 weekly installments- Step IV: Critiques of Draft Creed / Revised Statement

3 weekly installments- Step V: Personal Creed Presentation

1. Main Influences to Shape Me (My Experience)

2. What I Stand For (My Personal Creed)

3. Qualities to Develop in Myself Over Next 10 Years

4. How I Might be Serving or Helping Others in 10 Years to Honor My Creed (Optional: My Evolving Purpose)

These presentations, as Sharla hints above, are the most moving and, well, the deepest learning experience most students ever will experience in school. Here is the 16 week series of reflections students have undertaken to prepare for these presentations:

The Creed presentations are the only public rite of passage many students will ever have the chance to experience. They generate a collective excitement across the sophomore class at American High School, and may do so across other classes at other schools and colleges. In recent years, technology has become a key element of the experience. Numbers of students are breaking new ground in expressing their individuality in Creed videos. This past year, all sophomore English teachers but one at our school brought their sophomore English classes [about 80% of the sophomore class] through the Creed experience. Slowly, more students across the country are having this opportunity to discover themselves as part of their academic learning.

In 2001, I received the James Moffett Memorial Award for Teacher Research from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and the National Writing Project, in recognition of the Personal Creed Project. Slowly, in response to the workshops I have offered for a decade and a half at local, state, and national English conferences and conventions, and with the slow spread of my book about the Creed Project, ongoing Creed sites have begun to emerge at middle schools, high schools and colleges across North America. This past summer I was a featured speaker at the annual conference of NCTE’s Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning, my first chance to introduce the Creed Project and Model of Deepened Learning to larger audiences through public speaking. I am currently mentoring several professors of English and education who heard this talk and are at various stages of implementing the Creed Project with their college students in English and education programs. Nearly 200 English teachers are currently members of the social network I host for English teachers and professors, hopefully increasing outreach. Speaking of outreach . . . .

¶ Truthseeking to Torchpassing

In this community we generally think outreach means sharing The Urantia Book. The Urantia movement has recently begun to focus on doing more effective work passing the torch to a new generation. And there are some great efforts going on in this arena. Go YaYA!

I find myself dreaming of an additional kind of outreach. I believe the largest, most needful field of service is K-12 education. It is also the most ripe in its potential for assisting the planetary uplift: K-12 is the widest gate in our culture, the one gate almost all of us pass through. More souls await guidance toward a life of higher purpose in our public school classrooms than anywhere else. Perhaps in the years ahead the Urantia movement will see this and organize to support the transformation of education. This is a powerful option to consider, particularly if learning can usefully be regarded as the core drive of human evolution. For now, I hope the Personal Creed process and the Model of Deepened Learning can help prepare us for this coming transformation, in and beyond the Urantia movement. At this point, if you’d like to help, I can suggest three possibilities.

First, consider bringing your desire to serve into a classroom near you. If you are looking for a new career, consider teaching. There is great satisfaction in working to help young people develop themselves, especially when you are prepared with knowledge of—and a spiritual connection to—the larger universe. Much guidance is available to us. Imagine a network of fifth-epochally-inspired educators with an annual conference to attend for camaraderie and celestial guidance, for example.

Second, I am looking for assistance in consolidating the loose collection of schools and colleges currently adapting the Creed Project into an interconnected network of Creed sites around the world. Immediate needs include developing a stronger web presence and creating a way of funding my travel for workshops and speaking engagements.

Third, I am looking for a university researcher to design a study on the long term effects of the Creed project on students.

Every spring, before modeling the year’s first personal creed presentation in my classroom, I take the opportunity to update my own personal creed. Tuesday night, getting ready for my Wednesday workshop here at IC11, I again updated my creed. Keep in mind that the powerful effect of these presentations comes largely from the trusting relationships we have built up in a classroom over the year so far and the love that follows the trust. I have felt more of this kind of trust at this conference. So here is my updated personal creed:

My Creed Statement:

-

I stand for learning to love my family with more and more of my heart. “Family” begins with my blood family (including myself) and extends to my universe family.

-

I value sincerity.

-

I stand for doing my best to give loving attention to my wife and daughters, working with my wife to help our daughters develop into caring, loving, fulfilled adults.

-

I stand for helping young people create a world where their own children and grandchildren see more truth, beauty, justice, and compassion.

I’ll leave you with a last soul for you to scan. Asked to describe a moment in the course that had mattered to her, Shabnam chose the Personal Creed Project. Here she comments on what she felt was the significance of the project. She helped me understand something about purpose and heart.

I think this project made it clear for many students that they had a past, they have a present, and that they will have a future . . . it has gotten rid of that part of me that was unsure and skeptical about my future. Shabnam, class of 2010

It took two years for Shabnam to finally convince her Afghan refugee parents that they should allow her to attend college. She’ll be a sophomore at UC Davis in the fall. Her experience with the Creed Project and Deepened Learning may well have helped her in accomplishing this purpose. Let your soul be filled with purposes.

John Creger can be reached: Personal Creed Group: http://englishcompanion.ning.com/group/pers

¶ Bibliography

-

Creger, John. The Personal Creed Project and a New Vision of Learning: Teaching the Universe of Meaning in and Beyond the Classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2004.

-

Damon, William. The Path to Purpose: Helping our Children Find Their Calling in Life. New York, NY: Free Press, 2008.

¶ References

- Article obtained from The Fellowship site