[ p. 1 ]

¶ From Alexander to the Uprising of Mattathias (336-167 B.C.)

Alexander the Great .—The expeditions of Alexander the Great made possible the world culture in which the Christian gospel later found such ready acceptance. Had it not been for the unifying influence of his conquests, it would have been impossible for any religion to have spread with the rapidity that characterized the missionary success of Christianity in the first century. He was the first to accomplish the amalgamation of Greeks and Orientals. Cyrus the younger had attempted this in his campaign against his older brother Artaxerxes. The march of the ten thousand will always be a classic. But it remained for Alexander to so penetrate the east that Greek civilization became an integral part of the life of the orient. Thus the later advance of the Christian religion into western lands was made possible and natural.

Alexander the Great was born in 356 B.C., in the period when Greek culture was at its height. He was the pupil of Aristotle, and no doubt was influenced much by that great philosopher. After the assassination of Philip in 336, Alexander succeeded him as monarch and proceeded to make his position secure at home. Then, gathering an army of thirty or forty thousand men, he commenced the march eastward which his youthful mind had long been planning. In 334 B.C., at the battle of Granicus in Asia he routed the Persian forces and took the city of Sardis, along with other strongholds. Continuing eastward, he arrived in 333 at Issus near Antioch of Syria. There [ p. 2 ] Darius had gathered his forces for a determined stand. When Alexander delayed his attack Darius endeavored to make a detour through the hills and attack him from the rear. This gave Alexander his opportunity. Darius was caught in the defiles and his forces routed. Alexander then devoted seven months to reducing the city of Tyre. Another two months he encamped in front of Gaza. The winter of 332-331 he spent in Egypt. In 331 he set out for Persia. On the 20th of September, in 331, he crossed the Tigris. The eclipse of the moon which occurred at the crossing of the Tigris fixes the year and day. His further expeditions into Parthia, Bactria, and northern India do not concern our present study. In 323, in Babylon, while preparing for further expeditions, he contracted a fever, which proved fatal. When he was at the point of death, he requested his faithful army to pass through his bedroom one by one and bid him a last farewell.

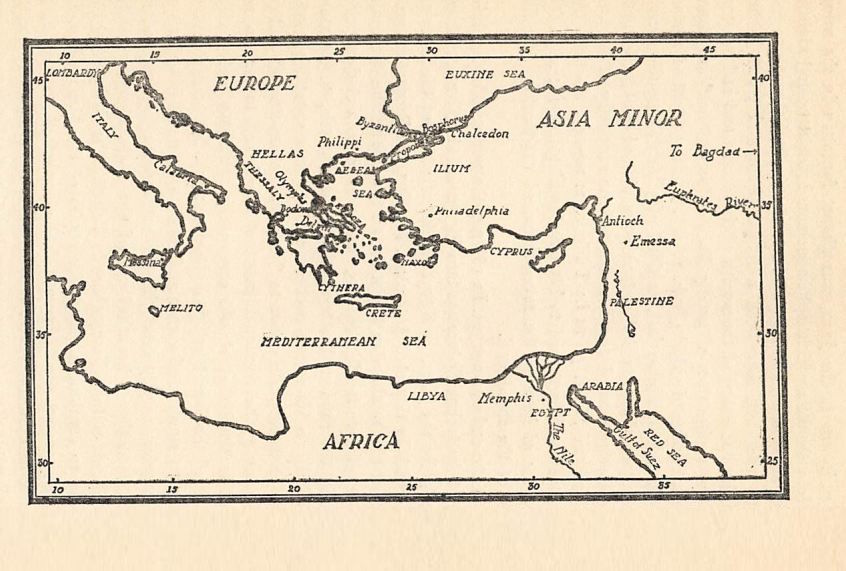

It is interesting to note how Alexander’s line of march parallels the line of march which early Christianity took in its advance. Alexander marched from Macedonia over into Asia, through Mysia and, crossing the mountains, fought his decisive battle near Antioch. He then spent some time at Tyre and Gaza, and paid his respects to the temple at Jerusalem. Christianity reversed the march, advancing from Jerusalem to Gaza, to Tyre, then down the coast. Its first great rallying-point was Antioch. It moved from Antioch northward and eastward, crossing the mountains in Asia and finally entering Macedonia. Alexander had made of one language all the nations of the eastern Mediterranean. Christianity used that one language in making itself intelligible to those same nations.

Front Alexander to Mattathias .—The empire which Alexander the Great had founded was divided up among the Diadochi, the “Successors.” In the apportionment, Coele-Syria, including Palestine, fell to Laomedon, and Egypt to Ptolemy Lagus. This division was of great importance to Palestine during the following centuries. If Egypt and Syria had been placed under one ruler instead of two, the subsequent history of Palestine [ p. 3 ] would have been very different. The wars between Syria and Egypt made Palestine again and again a bloody battle ground.

Ptolemy Lagus was not satisfied with his share of Alexander’s domain. He marched upon Jerusalem under pretense of wishing to worship in the Temple. Having entered the city on a Sabbath, he overwhelmed it with his troops and forced the Jews into subjection to Egypt. Laomedon was unable to recover his stolen property. Judea remained subject to Egypt, with only brief interruptions, to the year 198. Lagus was not a bad sovereign for the Jews. He demanded an annual tribute of twenty talents of silver, but this was the extent of their subjection.

During these hundred years and more, the Jews enjoyed a large measure of peace and prosperity. The high priest was held responsible by the Egyptian king for the payment of the annual tribute. He was supported by the military power of Egypt. The high priest thus became political head of the city-state, and the government may be fairly called a theocracy. The “Gerousia,” or Senate, of Jerusalem assisted in the management of affairs. This senate had probably developed out of the assembly of the heads of families of the time of Nehemiah.

The effect of the close relationship with Egypt was marked. Large numbers of Jews settled in Alexandria. Jewish scholars were naturally attracted there. The largest library in the world gathered about its treasures many of the scholars of the day. Freedom of thought was encouraged. Judaism and Hellenism shook hands with each other. The Old Testament was carefully translated into Greek, the language which Alexander had brought. This means of communication between Jewish thought and Hellenistic philosophy made possible the later propaganda of the Jewish Dispersion. Judaism was making itself at home in the world, as Christianity did later. Hellenism would have overwhelmed and submerged Judaism had not the inherent power and force of the Jewish faith asserted itself, both at home in Judea and abroad in Egypt and elsewhere. As Schiirer suggestively [ p. 4 ] states, Judaism is the only instance of an Oriental religion surviving the flood of Hellenistic thought and civilization (Schurer I-i-199).

In 198 B.C., Antiochus the Great, King of Syria, finally wrested Palestine from Egypt. Never again were the Jews under Egyptian rule. The decisive battle was fought at Panias.

Antiochus Epiphanes, son of Antiochus the Great, proceeded to destroy Judaism in order to make Palestine thoroughly Syrian. Antiochus Epiphanes was not primarily a bloodthirsty tyrant. In the subsequent history, the persecution was a matter of principle, rather than of personal animosity. He felt that the peace and prosperity of his domain lay in its thorough Hellenization. The few Jews who favored Hellenism naturally stood by him, and he just as naturally attached himself to them. It is almost a certainty that Hellenism would have ultimately supplanted Judaism had Antiochus not been too impatient and hasty.

The high priest in Jerusalem in 175 was Onias III. Jason, the brother of Onias, was jealous of him and aspired to his office. By promises and presents to Epiphanes he succeeded in gaining for himself the high-priesthood in 174 B.C. (II Macc. 4: 19-24). Jason was strongly Hellenistic in his sympathies, making many enemies among the Jews, not only by his part in the slaying of Onias III near the sanctuary of Daphne, but also by actual use of the temple moneys for secular purposes. In 171 B.C. he was expelled from his office by Menelaus, who had offered still larger bribes to the Syrian king and had thus gained the appointment as high priest (II Macc. 4: 26, 27).

The high-priesthood was becoming a mere plaything over which opposing claimants were quarreling. Jason, in 170 B.C., again seized the office and drove out his rival. This was done without the consent of Epiphanes. He then used this event as an excuse for interfering in Jerusalem. So the high-priesthood fell on evil days. Graft and bloodshed were the means of securing the office. But this abuse of the high-priesthood, hateful [ p. 5 ] as it was to the Jews, was almost forgotten in the more fearful calamities which Epiphanes now brought upon Judaism.

[ p. 6 ]

On his return from Egypt in 170 B.C., he had the excuse for doing what had long been a secret desire and greed in his soul. He had heard of the wealth of the temple and had coveted it. It was more than a “goodly Babylonish garment” and more than a “wedge of gold” (Josh. 7: 21). Under pretext of restoring the rightful high-priest, he sided with Menelaus and ordered a massacre of the people. He took possession of the temple, and, in real or pretended anger, ransacked the sanctuary of its possessions (II Macc. 5: 11 f.; I Macc. 1: 20-24). He “did his pleasure” and “returned to his own land” (Dan. 11: 28) with the altar of incense, the seven-branched candlestick, and the table of the shewbread.

But the end was not yet. In 168 B.C. the next and last expedition of Antiochus Epiphanes into Egypt ended still more disastrously for the Jews. In Egypt the interference of the Romans unexpectedly thwarted Antiochus. Popilius, the Roman general, ordered him to abandon Egypt for all time. When he demurred and asked time for deliberation, the general drew a circle around him in the sand and uttered the famous words, “Deliberate here!” Upon his return northward, Antiochus spent his wrath upon Jerusalem. He dared to “profane the sanctuary” and to “take away the continual burnt offering” and to set up an “abomination” that should completely annihilate and “make desolate” the Jewish religion (Dan. 11: 31). Massacres ensued and great numbers of women and children were sold into slavery.

Antiochus angrily determined to exterminate Judaism and to make Jerusalem a beautiful city of Greek art, Greek worship, and Greek culture. Everywhere in Palestine he charged Syrian officers to continue a search for copies of the Mosaic law. If they discovered any father who had circumcised his boy, they were to execute the father. In December, 168 B.C., a sacrifice to the Olympic Zeus finally desecrated the great altar at Jerusalem, and the Jews were compelled to march in Bacchic processions [ p. 7 ] wearing ivy wreaths. The Hellenization of Palestine seemed an accomplished fact.

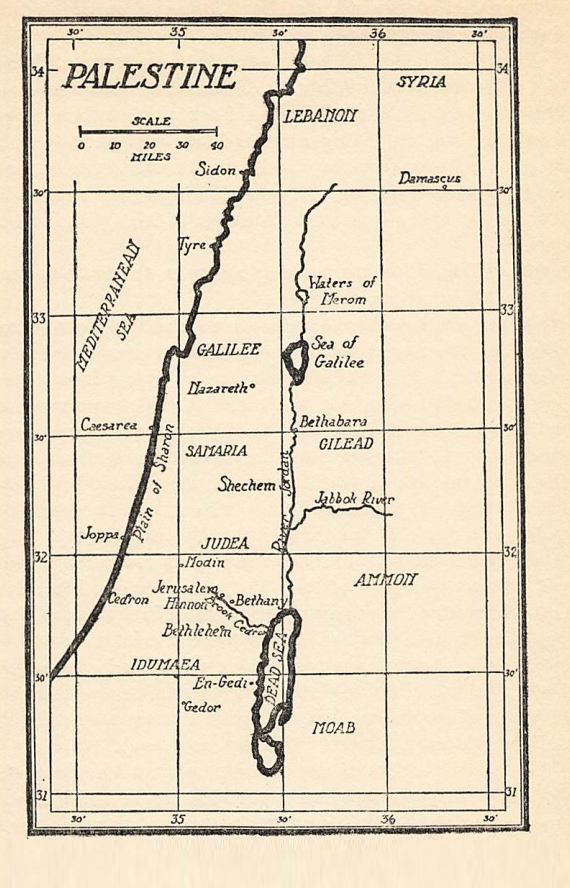

The Uprising of Mattathias .—In the little town of Modin, located on the sloping hills near Lydda, the smoldering fire of Jewish protest broke out. The first Book of Maccabees reflects the intensity of the feeling which had been pent up so long. No band of colonists rebelling against a British oppressor ever fought a more desperate battle; no Lexington or Bunker Hill witnessed a higher patriotism than that of Mattathias and his sons.

The officers of the Syrian king had come to Modin to carry out the king’s orders.

“And the king’s officers, who were enforcing the apostasy, came into the city of Modin to sacrifice. And many of Israel came to them, and Mattathias and his sons were gathered there. And the king’s officers said to Mattathias, ‘You are a ruler and an honourable and great man in this city, and strengthened with sons and brethren; now therefore come first and obey the commandment of the king, as all the nations have done, and the men of Judah, and those who remain in Jerusalem: and you and your house shall be among the number of the king’s friends, and you and your sons will be honoured with silver and gold and many gifts.’ And Mattathias answered in a loud voice, ‘Though all the nations that are in the house of the king’s dominion listen to him, to fall away each one from the worship of his fathers, and have made choice to follow his commandments, yet will I and my sons and my brethren walk by the covenant of our fathers. Heaven forbid that we should forsake the law and the ordinances’ ” (I Macc. 2: 15-21).

The refusal of Mattathias to offer sacrifice on the Syrian altar gave the opportunity to another Jew to win by his treason the favor of the Syrian king. This unknown Jew “came in the sight of all to sacrifice on the altar.” When Mattathias saw him “his zeal was kindled” and he ran and slew him; “and the king’s officer, who was compelling them to sacrifice, he killed at the same time, and pulled down the altar” (I Macc. 2: 25). Then [ p. 8 ] Mattathias cried out in the city, “Whoever is zealous for the law, and keeps the covenant, let him come forth after me” (I Macc. 2: 27). And he and his sons fled into the mountains.

[ p. 9 ]

“Many that sought after justice and judgment went down into the wilderness to dwell there” (I Macc. 2: 29). The forces of the Syrian king pursued them and battled against them on the Sabbath. The religious nature of the revolt is nowhere more clearly shown than here, for many of the Jews refused to fight on the Sabbath and were mercilessly hewn down to the number of a thousand souls. Mattathias called a council of war in which the patriots decided to fight to defend themselves if necessary, even on the Sabbath. Then Mattathias and his followers went up and down the land, destroying the Syrian altars and driving out the officers who represented the Syrian persecution.

But the rough life of the mountains was too great a change for Mattathias. He died in the year 166 B.C. when the uprising was scarcely a year old. His parting exhortation to his sons was that Judas be their captain in battle, and the older Simon be their counselor and advisor. “And his sons buried him in the sepulchre of his fathers at Modin” (I Macc. 2: 70).

The success of the uprising of Mattathias was due largely to the intensity of its religious motives. The first Book of Maccabees clearly reveals its religious character. In the struggle which followed the death of Mattathias, his desperate followers fought for something more than liberty and more than life. Whenever the struggle lost its religious character, it lost its appeal to the truest Jews and consequently failed.

While they were fighting for religious convictions and religious liberty, they were blessed with remarkable triumphs. As soon as the movement took a political turn, it began to lose its glory. These two facts were perhaps in the mind of Jesus and the disciples in the early days of Christianity. Jesus said, “Fear not those who are able to destroy the body only.” He told his disciples to have absolute confidence in their Heavenly Father as long as they were engaged in His work, spreading [ p. 10 ] His truth. Jesus had absolute faith in the success of the campaign for the spiritual Kingdom. On the other hand, he said, “Render to Ca;sar the things that are Caesar’s.” The early Christians paid their taxes. It was their policy to submit to the temporal powers. It may be that the Maccabean and later struggles helped to educate the Jews in the appreciation of this twofold truth that success attends the struggle for high spiritual life, but that they should not aspire to earthly and political independence and glory for their own sake.

The thoroughly religious beginning of this nationalistic movement may be clearly recognized. Its adherents were children of God like those among whom Christianity made its first start. The longing after God, the intense desire for spiritual freedom, the craving that the merciless plundering of a foreign despot might give way to the care of some human or divine Shepherd or Father, are all here. The people whom Judas fed and clothed were the kind of people whom Jesus fed and to whom John the Baptist said, “If you have two coats and your brother has none, give him one of yours” (Lk. 3: n). This brief review of the Maccabean struggle affords an insight into the hearts of these people to whom Jesus came and to whom he gave the revelation of God’s providential care.

¶ Judas Maccabeus (166-160 B.C.)

First Victories .—After the death of Mattathias, Judas began to strike here and there with rapidity and power. “He was like a lion in his deeds” (I Macc. 3:4). It was because of these blows that he was named Maccabaeus, the “Hammerer.”

“And he went about among the cities of Judah, and destroyed the ungodly out of the land, and turned away wrath from Israel: and he was renowned unto the utmost part of the earth, and he gathered together such as were ready to perish” (I Macc. 3 : 8-9).

Judas’ first expedition was against the Samaritan governor. “Apollonius gathered the Gentiles together, and a great host [ p. 11 ] from Samaria, to fight against Israel. And Judas perceived it, and he went forth to meet him, and smote him, and slew him: and many fell wounded to death, and the rest fled. And they took their spoils, and Judas took the sword of Apollonius, and therewith he fought all his days” (I Macc. 3: 10-12).

He next advanced against the Syrian forces under Seron (166 B.C.). Seron came with his mighty army to Bethhoron and Judas went forth to meet him with a small company. Judas exhorted his men to fight valiantly, leading them suddenly upon the Syrian forces. Seron’s army was put to flight and driven in disorder down into the plain. About eight hundred Syrians were killed.

Antiochus was greatly disturbed over the news of this defeat. Realizing, however, that the depleted condition of his treasury rendered him helpless, he decided that before extinguishing this little flame in Judea he would go into Persia “and gather much money.” He left Lysias in command of the affairs of his kingdom.

“And Lysias chose Ptolemy the son of Dorymenes, and Nicanor, and Gorgias, mighty men of the king’s friends; and with them he sent forty thousand footmen and seven thousand horse, to go into the land of Judah, and to destroy it, according to the word of the king. And they removed with all their host, and came and pitched near Emmaus in the plain country” (I Macc. 4: 38-40).

Although Judas was awed by the size of the Syrian host, he organized his men and immediately marched toward Emmaus. The strategy of Gorgias, the Syrian general, was outdone by the quickness and cleverness of Judas. Gorgias took five thousand footmen and one thousand horsemen and in the night made a sudden march against the band of Judas.

“And Judas heard thereof, and removed, he and the valiant men, that he might smite the king’s host which was at Emmaus, while as yet the forces were dispersed from the camp. And Gorgias came into the camp of Judas by night, and found no man” (I Macc. 3: 3-5).

[ p. 12 ]

Meanwhile Judas and his band had arrived at the camp of the Syrians “and they that were with Judas sounded their trumpets, and joined battle, and the Gentiles were discomfited, and fled into the plain. But all the hindmost fell by the sword: and they pursued them unto Gazara, and unto the plains of Idumea and Azotus and Jamnia, and there fell of them about three thousand men. And Judas and his hosts returned from pursuing after them, and he said unto the people, Be not greedy of the spoils, inasmuch as there is a battle before us; and Gorgias and his host are nigh unto us in the mountain. But stand ye now against our enemies, and fight against them.”

The Syrians with Gorgias, disappointed in not finding Judas, turned back to see their camp in flames and “they fled all of them into the land of the Philistines.” Judas and his band returned home and sang a song of thanksgiving and gave praise unto heaven. Israel had a great deliverance that day.

After this defeat of the Syrian generals at Emmaus, Lysias determined to take personal charge of the campaign against Judas. “And in the next year he gathered together threescore thousand horse, that he might subdue them. And they came into Idumea, and encamped at Beth-Zur; and Judas met them with ten thousand men” (I Maccabees 4: 28-29). “And they joined battle; and there fell of the army of Lysias about five thousand men” (I Macc. 4: 34). This victory at Beth-Zur in 165 B.c. marked a high point in the career of Judas.

Purification of the Temple .—Judas was now able to do that for which all his conflicts had been waged. He went up to Jerusalem, to restore the religion of Israel. “And they saw the sanctuary laid desolate, and the altar profaned, and the gates burned up, and shrubs growing in the courts” (I Macc. 4: 38). “And he chose blameless priests, such as had pleasure in the law: and they cleansed the holy place, and bare out the stones of defilement into an unclean place” (I Macc. 4: 42-43). “And they pulled down the altar . . . and they took whole stones according to the law, and built a new altar” (I Macc. 4: 47).

“And they made the holy vessels new, and they brought the [ p. 13 ] candlestick, and the altar of burnt offerings and of incense, and the table, into the temple. And they burned incense upon the altar, and they lighted the lamps that were upon the candlestick, and they gave light in the temple. And they set loaves upon the table, and spread out the veils, and finished all the works which they made” (I Macc. 4: 49-51).

This rededication of the temple took place, according to the Book of Maccabees, just three years after the Syrians had desecrated the altar, on the same day of the month Chislev (December) 165 B.C. “They kept the dedication of the altar eight days, and offered burnt offerings with gladness, and sacrificed a sacrifice of deliverance and praise” (I Macc. 4: 56).

This is the historical origin of the feast of Dedication which was celebrated every year by the Jews, down to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. “And Judas and his brethren and the whole congregation ordained that the days of the dedication of the altar should be kept in their seasons from year to year by the space of eight days” (I Macc. 4: 59). They then fortified Jerusalem with high walls and strong towers. They further fortified the city of Beth-Zur where Judas had won his victory; for they saw that the next campaign against them would be from that direction.

Before the Syrians came again, Judas had time to subdue the neighboring tribes who were always ready to take the part of Syria against him. “And Judas fought against the children of Esau in Idumea at Akrabattine, because they besieged Israel: and he smote them with a great slaughter, and brought down their pride, and took their spoils” (I Macc. 5: 3). He not only subdued the Idumeans, but he crossed the Jordan and fought with the children of Ammon.

“And he passed over to the children of Ammon, and found a mighty band, and much people, with Timotheus for their leader. And he fought many battles with them, and they were discomfited before his face; and he smote them, and got possession of Jazer, and the villages thereof, and returned again into Judea” (I Macc. 5: 6-7-8).

[ p. 14 ]

Meanwhile the Jews who were in Galilee and Gilead were being hard pressed by the people among whom they lived. The Jews of Gilead were compelled to take refuge in a stronghold called Dathema. They sent letters to Judas asking his aid. “While the letters were yet reading, behold, there came other messengers from Galilee with their clothes rent” (I Macc. 5: 14). With this twofold cry for assistance, Judas divided his forces. “And Judas said unto Simon his brother, Choose your men, and go and deliver your brethren that are in Galilee, and I and Jonathan my brother will go into the land of Gilead” (I Macc. 5: 17). “And unto Simon were divided three thousand men to go into Galilee, but unto Judas eight thousand men to go into the land of Gilead” (I Macc. 5: 20).

Simon was successful in Galilee and brought the Jews with their families and possessions into Judea. Judas had a much longer campaign in the country beyond Jordan, but his sudden, quick movements paralyzed the inhabitants of the desert. He went three days’ journey into the wilderness and then by a sudden turn surprised the city of Bosor and captured it. Removing abruptly by night, he came to the stronghold of Dathema, where the Jews had taken refuge. When Judas arrived, the fortress was being stormed by the hostile army of Timotheus.

And Judas saw that the battle was begun, and that the cry of the city went up to heaven” (I Macc. 5:31).

“And the army of Timotheus perceived that it was Maccabeus, and they fled from before him: and he smote them with a great slaughter, and there fell of them on that day about eight thousand men” (I Macc. 5: 34). After taking several other strongholds, he met a determined opposition at Raphon, but again the Gentiles “were discomfited before his face, and cast away their arms and fled” (I Macc. 5: 43).

“And Judas gathered together all Israel, them that were in the land of Gilead, from the least unto the greatest, and their wives, and their children, and their stuff, an exceeding great army, that they might come into the land of Judah” (I Macc. S:45)

[ p. 15 ]

On the return journey to Judea, Judas was forced to fight once more. The city of Ephron would not allow him to pass. “And the men of the host encamped, and fought against the city all day and all that night, and the city was delivered into his hands” (I Macc. 5: 50).

“And Judas gathered together those that lagged behind, and encouraged the people all the way through, until he came to the land of Judah. And they went up to Mount Sion with gladness and joy and offered whole burnt offerings, because not so much as one of them was slain until they returned in peace” (I Macc. 5: 53-54) It is of interest to note the ardor with which other Jewish leaders tried to imitate these exploits of the Maccabees. Joseph and Azarias determined to strike a blow at the Syrian hosts. Instead of defending Judea as they had been commanded, they marched against Jamnia in the plain. “And Gorgias and his men came out of the city to meet them in battle. And Joseph and Azarias were put to flight, and were pursued unto the borders of Judea; and there fell on that day of the people of Israel about two thousand men” (I Macc. 5: 59-60).

After his return from Gilead Judas led another expedition into the south and subdued the “children of Esau.” He took Hebron and the villages and strongholds in that vicinity. Then he marched into the land of the Philistines and pulled down their altars and took spoil of their cities.

The Death of Antiochus .—Antiochus Epiphanes died unexpectedly in 164 B.C. while he was still campaigning for riches and plunder in Persia. In the book of Maccabees is the striking statement that he died of a broken heart and bad conscience because of the manner in which he had treated the holy city, Jerusalem. “But now I remember the evils which I did at Jerusalem, and that I took all the vessels of silver and gold that were therein, and sent forth to destroy the inhabitants of Judah without a cause. I perceive that on this account these evils are come upon me, and behold, I perish through great grief in a strange land” (I Macc. 6: 13-14).

[ p. 16 ]

At his death he appointed Philip to be the guardian of his son Antiochus V. The rivalry which immediately ensued between Lysias and Philip produced the background for the next expedition of Lysias against Judas.

Judas now laid siege to the citadel of Jerusalem, which was still held by a Syrian garrison. Lysias, when he heard of the attack, gathered his hosts. The numbers given in I Maccabees are probably exaggerated, though reflecting truly the emotions of Judas and his small band in the face of superior numbers. “And the number of his forces was a hundred thousand footmen, and twenty thousand horsemen, and two and thirty elephants trained for war (I Macc. 6: 30). The Syrians made a detour as before and came toward Jerusalem from the south. The battle took place at Bethzacharias, which is between Jerusalem and Beth-Zur. Eleazar, the brother of Judas, was slain in the battle, and the forces of Judas were compelled to retire into Jerusalem. With the Syrian garrison inside and the Syrian army outside, there was little hope for Judas to hold any strategic position any length of time. But at this crisis the rivalry existing between Philip and Lysias saved the day for Judas. Judas was able to make a treaty with Lysias in which religious liberty was conceded to the Jews. After demolishing the walls of Jerusalem, an act contrary to his promise, Lysias hastened to Antioch to take possession of the Syrian throne and to expel Philip, who had already occupied that city.

The position of Judas was now in some ways unfortunate. The revolt had aimed only at religious liberty. Now that this had been formally conceded by Lysias, the revolt lost its purpose and its glory. It was dangerous to lay down arms, yet there was nothing to be attained by further use of them. The driving spirit of the uprising rapidly lost its pristine power.

Accession of Demetrius I .—After Lysias had expelled Philip from Antioch he found a still more powerful opponent in Demetrius, a rightful heir to the Syrian throne (I Macc. 7:1). Demetrius received the support of the army, easily overcame Lysias and then put him to death.

[ p. 17 ]

Demetrius now found an ally against the Jews. Alcimus, a Jew of the priestly line, requested Demetrius to make him high priest. Demetrius appointed “that ungodly Alcimus” (I Macc. 7:9), and sent his general, Bacchides, to aid his appointee in completely subduing the Jews. Because Alcimus was of the priestly line the more pious Jews were persuaded to put faith in himT “And Bacchides spoke with them words of peace, and swore to them, saying, we will seek the hurt neither of you nor your friends. And they gave him credence; and he laid hands on threescore men of them, and slew them in one day” (I Macc. 7: 15-16). The terror of Alcimus and Bacchides fell upon all the people.

As soon as Bacchides departed, the Jews again rallied to Judas. Alcimus grew afraid and reported the situation to the king. Demetrius sent his general, Nicanor, to cope with Judas. “And Nicanor came to Jerusalem with a great host; and he sent unto Judas and his brethren deceitfully with words of peace, saying, Let there be no battle between me and you; I will come with a few men, that I may see your faces in peace” (I Macc. 7: 27-28). He would have treacherously seized Judas, whom he rightly perceived to be the real power in Judea, but Judas was too clever. Nicanor was forced to meet him in open battle. “And he went out to meet Judas in battle beside Capharsalama; and there fell of Nicanor’s side about five hundred men” (I Macc. 7: 31-32).

Nicanor marched on into Jerusalem. Reinforcements arrived which he went to meet at Bethhoron. “And Judas encamped in Adasa with three thousand men.” “And on the thirteenth day of the month Adar the armies joined battle; and Nicanor’s army was discomfited, and he himself was the first to fall in the battle. Now when his army saw that Nicanor was fallen, they cast away their arms, and fled. And they pursued after them a day’s journey from Adasa until you come to Gazara, and they sounded an alarm after them with solemn trumpets. And they came forth out of all the villages of Judea round about, and they all fell by the sword, and there was not one of [ p. 18 ] them left. And they took the spoils and the booty, and they smote off Nicanor’s head and his right hand, which he stretched out so haughtily, and brought them to Jerusalem. And the people was exceeding glad, and they kept that day as a day of great gladness. And they ordained to keep this day year by year, to wit, the thirteenth day of Adar. And the land of Judah had rest a little while” (I Macc. 7: 40, 43-50).

In the interval of peace which followed this great victory (161 B.C.) Judas chose ambassadors and sent them to Rome to make a treaty. The Romans were only too willing to make such a treaty and sent back to Jerusalem a document insuring mutual protection which exactly suited the Jews. The only drawback to the beautiful arrangement lay in the fact that Rome did not exert herself in behalf of the Jews until she saw a good chance to crush Syrian power in the East, and supplant it by her own sway. But the covenant sounded well. “Good success be to the Romans and to the nation of the Jews, by sea and by land forever; the sword also and the enemy be far from them. But if war arise for Rome first, or any of their confederates in all their dominion, the nation of the Jews shall help them as confederates as the occasion shall prescribe to them, with all their heart; and unto them that make war upon them they shall not give, neither supply, food, arms, money, or ships, as it has seemed good unto Rome, and they shall keep their ordinances without taking anything therefor. In the same manner, moreover, if war come first upon the nation of the Jews, the Romans shall help them as confederates with all their soul, as the occasion shall prescribe to them; and to them that are confederates with their foes there shall not be given food, arms, money, or ships, as it has seemed good unto Rome; and they shall keep these ordinances, and that without deceit. According to these words have the Romans made a covenant thus with the people of the Jews” (I Macc. 8: 23-29).

Meanwhile, Demetrius, hearing that Nicanor had been killed, sent Bacchides to aid Alcimus again. Then ensued Judas’ last battle. For some reason, the courage of Judas’ band failed in [ p. 19 ] the face of the great Syrian army. “And Judas was encamped at Alasa, and three thousand chosen men with him; and they saw the multitude of the forces, that they were many, and they feared exceedingly; and many slipped away out of the army; there were not left of them more than eight hundred men.” “And the men of Judas’ side, even they sounded with their trumpets and the earth shook with the shout of the armies, and the battle was joined, and continued from morning until evening. And Judas saw that Bacchides and the strength of his army were on the right side, and there went with him all that were brave in heart, and the right wing was discomfited by them, and he pursued after them unto the Mount Azotus. And they that were on the left wing saw that the right wing was discomfited and they turned and followed upon the footsteps of Judas and of those that were with him; and the battle waxed sore, and many on both parts fell wounded to death. And Judas fell and the rest fled” (I Macc. 9: 6-13, 18).

Such was the end of Judas. He was truly a great “Hammerer” and struck many a blow at the Syrian army until he himself was laid low. He did as much good in his death as in any of his great achievements in life, for his brothers and followers rallied to avenge his death. He was buried with great mourning at his home town, Modin. “And the rest of the acts of Judas, and his wars, and the valiant deeds which he did, and his greatness, they are not written; for they were exceeding many” (I Macc. 9: 22. Cf. John 21: 25).

¶ SUPPLEMENTARY READING

Breasted, Ancient Times , pp. 425-444.

Encyclopaedia Brittanica, art. Alexander the Great .

Fairweatiier, Background of the Gospels , pp. 95-115*

Fairweather, The First Book of Maccabees , pp. 53 _I 7 °*

Kent, Biblical Geography and History , pp. 3 ~ 44 > 207-221.

Mathews, History of New Testament Times , pp. i- 3 d*

McCown, The Genesis of the Social Gospel , pp. 37 ~ 74 *

Schurer, The Jewish People in the Time of Jesus , Div. I, Vol. I, pp. 186-233.

[ p. 20 ]

¶ THE RULERS OF SYRIA

33S-323 Alexander the Great.

175-164 Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

164-162 Antiochus V Eupator, son of Epiphanes.

162-150 Demetrius I Soter, cousin of Eupator.

153-145 Alexander Balas, son (?) of Epiphanes.

147-138 Demetrius II Nicator, son of Demetrius I.

145-138 Trypho, general of Alexander Balas, with the child, Antiochus VI, son of Alexander Balas.

138-128 Antiochus VII Sidetes, brother of Demetrius II.

128-125 Demetrius II (a second time).

128-122 Alexander Zabinas, son (?) of Alexander Balas.

125-124 Seleucus V, son of Demetrius II.

124-113 Antiochus VIII Grypos, brother of Seleucus V.

113-95 Antiochus IX Cyzicenos, cousin and brother of Grypos.

111—96 Antiochus VIII (a second time).

95-83 Five sons of Grypos (1) Seleucus VI, (2) Antiochus XI, (3) Philip, (4) Demetrius III, Eucaerus, (5) Antiochus XII contended with Antiochus X Eusebes, son of Antiochus Cyzicenos.

83-69 Tigranes, king of Armenia ruled Syria.

69-65 Antiochus XIII Asiaticus, son of Antiochus Eusebes.

65 Pompey made Syria a Roman Province.