[ p. 503 ]

¶ NOTE I

LUCRETIUS AND BOSSUET ON THE EARLY EVOLUTION OR MAN

Lucretius’s conception[1] of the gradual development of human culture undoubtediy came from Greek sources beginning with Empedocles. His indebtedness is beautifully expressed in the opening lines of Book III of his De Remm Natura :

“O Glory of the Greeks I who first didst chase

The mind’s dread darkness with celestial day,

The worth illustrating of human life—

Thee, glad, I follow — with firm foot resolved

To tread the path imprinted by thy steps;

Not urged by competition, but, alone,

Studious thy toils to copy; for, in powers,

How can the swallow with the swan contend?

Or the young kid, all tremulous of limb,

Strive with the strength, the fleetness of the horse;

Thou, sire of science 1 with paternal truths

Thy sons enrichest: from thy peerless page,

Illustrious chief I as from the flowery field

Th’ industrious bee culls honey, we alike

Cull many a golden precept—golden each —

And each most worthy everlasting life.

For as the doctrines of thy godlike mind

Prove into birth how nature first uprose,

Ail terrors vanish; the blue walls of heaven

Fly instant — and the boundless void throughout

Teems with created things.”

The same conception[2] of the early periods in the development of humanity is found in the Histoire universelle of Bossuet, in a curious passage undoubtedly suggested by Lucretius :

“Tout commence: il n’y a point d’histoire ancienne ou il ne paraisse, non seulement dans ces premiers temps, mais encore longtemps apres, des vestiges manifestes de la nouveaute du monde. On voit les lois s’etablir, [ p. 504 ] les moeurs se polir, et les empires se former: le genre humain sort pen a pen de Fignorance; l’experience rinstruit, et les arts sont inventes on perfectionnes. A mesure que les hommes se multiplient, la terre se penple de proche en proche: on passe les montagnes et les precipices; on traverse les fieuves et enfin les mers, et on etablit de nouvelles habitations. La terre, qui n’etait an commencement qu’une foret immense, prend une autre forme; les bois abattus font place aux champs, aux piturages, aux hameaux, aux bourgades, et enfin aux villes. On s’instruit a prendre certains animaux, a apprivoiser les autres, et a les accoutumer au service. On eut d’abord a combattre les b^tes farouches: les premiers heros se signalkent dans ces guerres; elles firent inventer les armes, que les hommes tournerent apres centre leurs semblables. Nemrod, le premier guerrier et le premier conquerant, est appele dans Fecriture un fort chasseur. Avec les animaux, Fhomme sut encore adoucir les fruits et les plantes ; il plia jusqu’aux metaux a son usage, et peu a peu il y fit servir toute la nature.”

¶ NOTE II

HORACE ON THE EARLY EVOLUTION OF MAN

Horace[3] also adopted the Greek conception of the natural evolution of human culture:

“Your men of words, who rate all crimes alike,

Collapse and founder, when on fact they strike

Sense, custom, all, cry out against the thing,

And high expedience, right’s perennial spring.

When men first crept from out earth’s womb, like worms.

Dumb speechless creatures, with scarce human forms,

With nails or doubled fists they used to fight

For acorns or for sleeping-holes at night;

Clubs followed next; at last to arms they came,

Which growing practice taught them how to frame,

Till words and names were found, wherewith to mould

The sounds they uttered, and their thoughts unfold;

Thenceforth they left off fighting, aiid began

To build them cities, guarding man from man,

And set up laws as barriers against strife

That threatened person, property, or wife.

’Twas fear of wrong gave birth to right, you’ll find,

If you but search the records of mankind.

Nature knows good and evil, joy and grief,

But just and unjust are beyond her brief:

Nor can philosophy, though finely spun,

By stress of logic prove the two things one,

To strip your neighbor’s garden of a flower

And rob a shrine at midnight’s solemn hour.”

[ p. 505 ]

¶ NOTE III

AECHYLUS ON THE EARLY EVOLUTION OF MAN

AEschyius, in Prometheus Bound,[4] presents one of the earliest known as well as one of the noblest conceptions of the natural development of the human faculties:

And let me tell you—not as taunting men,

But teaching you the intention of my gifts,

How, first beholding, they beheld in vain.

And hearing, heard not, but, like shapes in dreams,

Mixed all things wildly down the tedious time.

Nor knew to build a house against the sun

With wicketed sides, nor any woodwork knew,

But lived, like silly ants, beneath the ground

In hollow caves unsunned. There came to them

No steadfast sign of winter, nor of spring

Flower-perfumed, nor of summer full of fruit.

But blindly and lawlessly they did all things,

Until I taught them how the stars do rise

And set in mystery, and devised for them

Number, the inducer of philosophies.

The synthesis of Letters, and, beside,

The artificer of all things.

Memory That sweet Muse-mother.”

¶ NOTE IV

‘UROCHS,’ OR ‘AUEROCHS,’ AND ‘wisent’

Kobelt[5] discusses the habits of the wild cattle and of the bison as follows:

“ One is inclined to consider the ancient wild cattle of Europe, the Urochs, or Auerochs, as the inhabitants of boggy forests. The Auerochs survived to the seventeenth century in the forests of Poland and then became extinct. It is described as of a black color with a light stripe along the back.

“The bison, or Wisent, is generally regarded as the inhabitant of the open steppe, or at least of dryer, opener woods; it differs so little from the American bison that both can be considered only as races of one species, the Bison priscus of Pleistocene times, which spread over the temperate zone of both hemispheres. The American bison has always avoided the w^oods and roamed the prairies in countless herds. But all reliable historic records describe the Wisent as a forest animal, and its few remaining survivors are [ p. 506 ] entirely limited to the forests. Apparently it was never so widely and generally distributed as the Auerochs and reached western Europe later, for it is not found in the north, and never in conjunction with the maninui and rhinoceros. Remains of the bison have also been found in Asia Minor. In Lithuania the bison lives together in herds, resenting the approach of all strangers. In the Caucasus it lives wild in certain high valleys and here it is a true mountain animal, its favorite haunts being the forests of beech, hornbeam, and evergreens from. 4,000 to 8,000 feet above sea-level. Only in winter does it descend to lower levels. It is uncertain whether the Wisent does not also occur in Siberia. Kohn and Andree assert positively that it is found in large numbers in the wooded mountains of Sajan, in Siberia (1895).”

According to Kobelt, much confusion in the nomenclature of these animals has resulted from the fact that, after the extinction of the ‘Urochs,’ or ‘Auerochs,’ in the seventeenth century, the term ‘Auerochs’ was frequently used by writers as synonymous with ‘Wisent,’ or bison, an entirely different animal.

¶ NOTE V

THE CRÔ-MAGNONS OE THE CANARY ISLANDS[6]

“In the museums of the Grand Canary, Teneriffe, and Palma a considerable number of prehistoric vessels are preserved. Anthropologists are agreed that the natives of the archipelago at the time of its conquest, in the fifteenth century, were a composite people made up of at least three stocks: a Crô-Magnon type, a Hamitic or Berber type, and a brachycephalic type. These natives were in a Neolithic stage of civilization. Their arms were slings, clubs, and spears. Most of the people went naked, except for a girdle round the loins, and there was no intercommunication between the islands. Their stone implements were of obsidian or of basalt. Only four polished axes are known from the Grand Canary and one from Gomera. The axes are of chloromelanite, and of a type contemporary with megalithic structures in France. The first colonists probably brought the knowledge of making pottery with them, but each island developed an individuality of its own. Even the painted ware of the Grand Canary appears to be of local origin and not due to external influence. Although undoubted Lybian inscriptions in the Grand Canary and lava querns of Iron Age type prove that the archipelago was visited before its conquest by the Spaniards without affecting the general civilization of its inhabitants.”

[ p. 507 ]

GUANCHE CHARACTERISTICS RESEMBLING CRO-MAGNON[7]

The following excerpts are quoted from the account given by the distinguished anthropologist, Dr. Rene Verneau, of his observations during a five years’ residence in the Canary Islands.

Page 22.

“Without doubt the race that has played the most important role in the Canaries is the Guanche. They were settled in all the islands, and in Teneriffe they preserved their distinctive characteristics and customs until the conquest by Spain in the fifteenth century.

“The Guanches, who at that time were described as giants, were of great stature. The minimum measure of the men was 1.70 m. (5 ft. 7 in.).

“I myself met a number of men in the various islands who measured over 1.80 m. (5 ft. ii in.). Some attained a height of 2 m. (6 ft. 61 in.). At Fortaventure the average height of the men was 1.84 m. (6 ft. fa in.), perhaps the greatest known in any people.

“It is a curious fact that the women who gave birth to such men were comparatively small — I observed a difference of about 20 cm. (8 in.) in the heights of the two sexes.

“Their skin was light colored — if we may believe the poet Viana— and sometimes even absolutely white. Dacil, the daughter of the last Guanche chief of Teneriffe, the valiant Bencomo, w^ho struggled so heroically for the independence of his country, had a very white complexion and her face was quite freckled. The hair of the true Guanche should be blond or light chestnut, and the eyes blue.

“The most striking characteristic of the Guanche race was the shape of the head and the features of the face. The long skull gave shape to a beautiful forehead, well developed in every way. Behind, above the occipital, one notices a large plane contrasting strongly with the marked prominence of the occipital itself. In addition, the parietal eminences, placed very high and very distinct from each other, combined to give the head a pentagonal form.”

Page 29.

“The Guanche chiefs were much respected. At Teneriffe the coronation of the chief took place in an enclosure surrounded with stones (the Togaror), in the presence of nobles and people. One of his nearest kinsmen brought him the insignia of power. According to Viera y Clavijo, this was the humerus of one of his ancestors, carefully preserved in a case of leather; according to Viana, it was the skull of one of his predecessors.

“The chief (Menceg) placed the relic on his head, pronouncing the sacramental formula: T swear upon the bone of him who has borne this royal crown, that I will imitate his acts and work for the happiness of my [ p. 508 ] subjects.’ Each noble, in turn, then received the bone from the hands of the chief, placed it upon his shoulder and swore fidelity to his sovereign. . . . These chiefs led a very simple life: their food was like that of the people, their apparel but little more elaborate, and their dwellings— -like those of their subjects— consisted of camSy only theirs were a little larger than those of the common people. They did not disdain to inspect their flocks or their harvests in person, and were, indeed, no richer than the average mortal.”

Page 31.

“Above all, the ancient Canarians sought to develop strength and agility in their children. From an early age the boys devoted themselves to games of skill in order to fit them to become redoubtable warriors. The men delighted in all bodily exercises and, above all, in wrestling. At Gran Canaria (Grande Canarie) they often held veritable tourneys, which were attended by an immense number of people. These could not take place without the consent of the nobles and of the high priest.

“Permission obtained, the combatants presented themselves at the place of meeting. This was a circular or rectangular enclosure, surrounded by a very low wall, allowing free view of the details of the combat. Each warrior took his place upon a stone of about 40 cm. diameter (15 1 in.). His offensive weapons consisted of three stones, a club, and several knives of obsidian: his defensive weapon was a simple lance. The skill of defense consisted in evading the stones by movements of the body, or parrying the blows with the lance, without moving from the stone on which stand had been taken. These combats often resulted fatally for one of the combatants.”

Page 34.

“The Guanche understood the use of the sword, and although it was of wood (pine), it could cut, they say, as if it were of steel.

“To parry blows, they used a lance, as mentioned above, but they also had shields made of a round of the dragon-tree (Dracaena draco),

“The Guanches were essentially shepherds. While their flocks pastured they played the flute, singing songs of love or of the prowess of their ancestors. Those songs which have come down to us show them to have been by no means devoid of poetic inspiration.

“When the care of their stock permitted, they employed their leisure in fishing. For this they employed various means — sometimes nets, sometimes fish-hooks, sometimes a simple stick.”

Page 47.

“The Guanches were above all troglodytes — that is to say, they lived in caves. There is no lack of large, well-sheltered caves in the Canary Islands. The slopes of the mountains and the walls of their ravines are honeycomiDed with them. The islanders may have their choice.

[ p. 509 ]

“The caves are almost never further excavated. They are used just as they are.

“Here is a description of one of these caves, the of Goldar:

“The interior is almost square— -5 m. (16 ft. 4 in.) along the left side, 5 50 m. (18 ft.) along the right. The width at the back is 4.80 m. (15 ft. 6 in.). A second cave, much smaller, opens from the right wail. All these walls are decorated with paintings. The ceiling is covered with a uniform^ coat of red ochre, while the wails are decorated with various geometric designs in red, black, gray, or white. High up runs a sort of cornice painted red, and on this background, in white, are groups of two concentric circles, whose centre is also indicated by a white spot. On the rear wall the cornice is interrupted by triangles and stripes of red.”

Page 61.

“The Guanches never polished their stone weapons.”

Page 168.

“Inhabited caves are very numerous at Fortaventure. The population in certain parts — Mascona, for example — must be quite numerous to judge by the number of these caves. At a little distance, in the place known as Hoya de Corralejo, one may still see the Togaror, or tribal meeting place. It is an almost circular enclosure about 40 m. (131 ft. 2 in.) in diameter, surrounded by a low wall of stones. Six huts, from 2.50 to 4 m. (8 ft. in. — 13 ft. 1 ½ in.) in diameter, designed no doubt for the sacred animals, stood near the Togaror.”

Page 245.

“A great number of Canarians still live in caves. Near Caldera de Bandama (Gran Canaria) there is a whole village of cave dwellers.”

Page 264.

At Teneriffe Dr. Verneau received hospitality in a cabin worthy of the Palaeolithic Age.

“I had no need to make any great effort to imagine myself with a descendant of those brave shepherds of earlier times. My host was an example of the type— even though the costume was lacking — and his dwelling completed the illusion. The walls, which gave free access to the wind, supported a roof composed of unstripped tree trunks covered with branches. Stones piled on top prevented the wind from tearing it off.

“Hung up on poles to dry were goatskins, destined to serve as sacks for the gofio (a kind of millet), bottles for water, and shoes for the family. A reed partition shut off a small corner where the children lay stretched out pell mell on skins of animals. For furniture, a chest, a hollowed- put stone which served as a lamp, shells which served the same purpose, a water jar, three stones forming a hearth in one corner, and that was ali.”

(And this host was the most important personage in the place.)

[ p. 510 ]

Page 289.

Another time, also at Teneriffe, Dr/ Verneau had a similar experience “An old shepherd invited me to his house and offered me some milk. What was my surprise on seeing the furnishing of his hut! In one corner was a bed of fern, near by a Guanche mill and a large jar, in all points similar to those used by the ancient islanders. A reed flute, a wooden bowl and a goatskin sack full of gofio completed the appointments of his home. I could scarcely believe my eyes on examining the jar and the mill. Seeing my astonishment, the old man .explained that he had found them in a cave where ‘the Guanches’ lived, and that he had used them for many years. I could not persuade him to part with these curiosities. To my offers of money he answered that he needed none for the short time he had still to live.”

¶ NOTE VI

THE LENGTH OF POSTGLACIAL TIME AND THE ANTIQUITY OF THE AURIGNACIAN CULTURE

The most recent discussion on the length of Postglacial time was that held at the Twelfth International Congress of Geology, in Ottawa, in 1913 (Congres Geologique International, Compte-rendu de la XII Session, Canada, 1913, pp. 426-537). The notes abstracted by Dr. Chester A… Reeds from the various papers are as follows:

“American estimates of Postglacial time have been made chiefly from the recession of waterfalls since the final retreat of the great ice-fields in North America. The retreat of the Falls of St. Anthony, Minnesota, has been estimated by Winchell at 8,000 years and by Sardeson at 30,000 years. The retreat of- the Falls of Niagara has been estimated as requiring from

7,000 to 40,000 years; it has proved a very uncertain chronometer, because of the great variation in the volume of water at different stages in its history, The recession of Scarboro Heights and other changes due to wave action on Lake Ontario have been estimated by Coleman as requiring from 24.000 to 27,000 years. Fairchild has estimated that 30,000 years have elapsed since the ice left the Lake Ontario region of New York.

“ In Europe the most accurate chronology is that of Baron de Geer on the terminal moraines and related marine clays of northern Sweden. For the retreat of the ice northward over a distance of 370 miles in Sweden 5,000 years were allowed; for the time since the disappearance of the ice in Sweden, 7,000 years; for the retreat of the ice from Germany across the Baltic, 12,000 years; giving a total of 24,000 years as compared with a total of between 30,000 and 50,000 years allowed by Penck for the retreat of the ice-fields of the Alps.”

[ p. 511 ]

¶ NOTE VII

THE MOST RECENT DISCOVERIES OR ANTHROPOID APES AND SUPPOSED ANCESTORS OE MAN IN INDIA

It is possible that within the next decade one or more of the Tertiary ancestors of man may be discovered in northern India among the foot-hills known as the Siwaliks. Such discoveries have been heralded, but none have thus far been actually made. Yet Asia will probably prove to be the centre of the human race. We have now discovered in southern Asia primitive representatives or relatives of the four existing types of anthropoid apes, namely, the gibbon, the orang, the chimpanzee, and the gorilla, and since the extinct Indian apes are related to those of Africa and of Europe, it appears probable that southern Asia is near the centre of the evolution of the higher primates and that we may look there for the ancestors not only of prehuman stages like the Trinil race but of the higher and truly human types.

As early as 1886 several kinds of extinct Old World primates, including two anthropoid apes related to the orang and to the chimpanzee, were reported from the Siwalik hills in northern India, and recently Dr. Pilgrim, of the Geological Survey, has described three new species of Siwalik apes resembling Dryopithecus of the Upper Miocene of Europe, also an anthropoid which he has named Sivapithecus and regards as actually related to the direct ancestors of man, a conclusion which may or may not prove to be correct. Another extinct Indian ape, Palaeopithecus, is of very generalized type and is related to all the anthropoid apes.

¶ NOTE VIII

ANTHROPOID APES DISCOVERED BY CARTHAGINIAN NAVIGATORS[8]

The Periplus of Hanno purports to be a Greek translation of a Carthaginian inscription on a tablet in the “temple of Chronos” (Moloch) at Carthage, dedicated by Hanno, a Carthaginian navigator, in commemoration of a voyage which he made southward from the Strait of Gibraltar along the western coast of Africa as far as the inlet now known as Sherboro Sound, the next opening beyond Sierra Leone.

Hanno is a very common Carthaginian name, but recent writers think it not improbable that this Hanno was either the father or the son of that Hamilcar who led the great Carthaginian expedition to Sicily in 480 B. C. In the former case the Periplus might be assigned to a date about 520 B. C.; in the latter, some fifty years later.

The narrative was certainly extant at an early period, for it is cited in the work on Marvellous Narratives ascribed to Aristotle, which belongs to [ p. 512 ] the third century B* C., and Pliny also expressly refers to it. The authenticity of the work is now generally conceded.

According to the narrative the farthest limit of Hanno’s voyage, which was undertaken for purposes of colonization, brought him and his companions to an island containing a lake with another island in it which was full of wild men and women with hairy bodies, called by the interpreters gorillas. The Carthaginians were unable to catch any of the men, but they caught three of the women, whom they killed, and brought their skins back with them to Carthage. “Pliny, indeed, adds that the skins in question were dedicated by Hanno in the temple of Juno at Carthage, and continued to be visible there till the destruction of the city. There can be no difficulty in supposing these Sviid men and women Vto have been really large apes of the family of the chimpanzee, or pongo, several species of which are in fact found wild in western Africa, and some of them, as is now well known, attain a stature fully equal to that of man.”

¶ NOTE IX

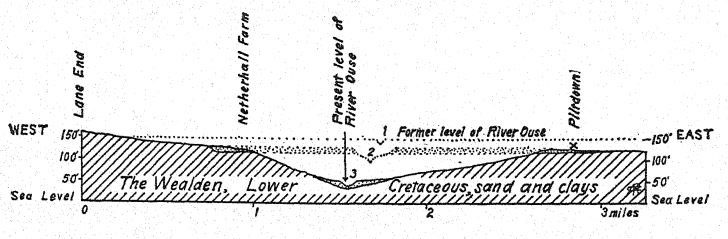

THE JAW AND SKULL OF THE PILTDOWN MAN

The skull and jaw fragments, as described on pages 130–144, on which were founded the new genus and species of the human race, Eoanthropus dawsoni, have aroused a wide difference of opinion among anatomists which is still (February, 1918) unsettled.

Many anatomists questioned the association of the Piltdown jaw with the Piltdown skull. Some anatomists held that the jaw is not prehuman and does not belong with the skull at all. After reconsidering the original discovery and subsequent geological and anatomical evidence, Dr. A. Smith Woodward still (letter of January 27, 1917) feels convinced that the jaw and skull fragments are prehuman and belong to a single individual of the Piltdown race. His opinion is supported by W. P. Pycraft, D. M. S. Watson, and other British anatomists who have made a very careful investigation and comparison of the original Piltdown specimens with similar bones of anthropoid apes.

On the other hand, Gerrit S. Miller, Jr.,[9] from a careful comparative study of a cast of the Piltdown jaw with the jaws of various types of chimpanzee, still maintains that the portions of the Piltdowm jaw preserved, including the upper eye-tooth, or canine, are genericaily identical with those of an adult chimpanzee. This new species of chimpanzee, wffiich Miller believes to be characteristic of the European Pleistocene, he names Fan veins. If Miller’s theory be correct it would deprive the Piltdown specimen of its jaw and incline us to refer the Piltdown skull to the genus Homo rather than to the supposed more ancient genus Eoanthropus. [ p. 513 ] Millers theory, however, has not been strengthened by the recent researches of the British Museum above alluded to, nor by the additional excayations of Smith Woodward near the locality where the jaw was found, both of which are said to confirm the original opinion of Dawson and Smith Woodward that the jaw belongs with the skull.

As to the geological age of the Piltdown race, if confirmed by future discovery, the presence in Germany near Taubach, Weimar, of teeth similar to those in the Piltdown jaw, found in Sussex, England, would tend to confirm the opinion expressed in the first edition of this work that the Piltdown race belongs to Third Interglacial times.

¶ NOTE X

FAMILY SEPULTURE OE LA FERRASSIE, FRANCE

The only instance of the knee-flexed burial position known in the Lower Palaeolithic is the unique family sepulture at the Mousterian station of La Ferrassie, in Dordogne, discovered by D. Peyrony in the years igog-igii. It includes the remains of two adults and two children. One of the adult skeletons lay upon its back with the legs strongly flexed. The body lay upon the floor of the cave without any sign of a cavity to contain it. The head and shoulders had been protected and surrounded by slabs of stone, while the rest of the body may have been covered by pelts or woven branches. The second skeleton was that of a woman with the arms folded upon the breast, while the legs were pressed against the body, indicating that they were bound with cords or thongs. Two children were interred in shallow graves.

This sepulture, like that of Spy, Belgium, of late Mousterian times, was apparently a case of genuine burial, testifying to the ancient reverence for the dead, joined, perhaps, with the belief in a life after dea 1. In the Ferrassie burial, close to the children’s remains, there w;as a ave filled [ p. 514 ] with ashes and bones of the wild ox. Similarly, in the interment at La Chapelle-aux-Saints there was a cavity containing a bison horn and a second cavity where large bones of the same animal were found, indicating possibly the remains of sacrificial offerings or funeral feasts.

¶ NOTE XI

PALEOLITHIC HISTORY OP NORTHWESTERN AFRICA AND SOUTHERN ’

SPAIN

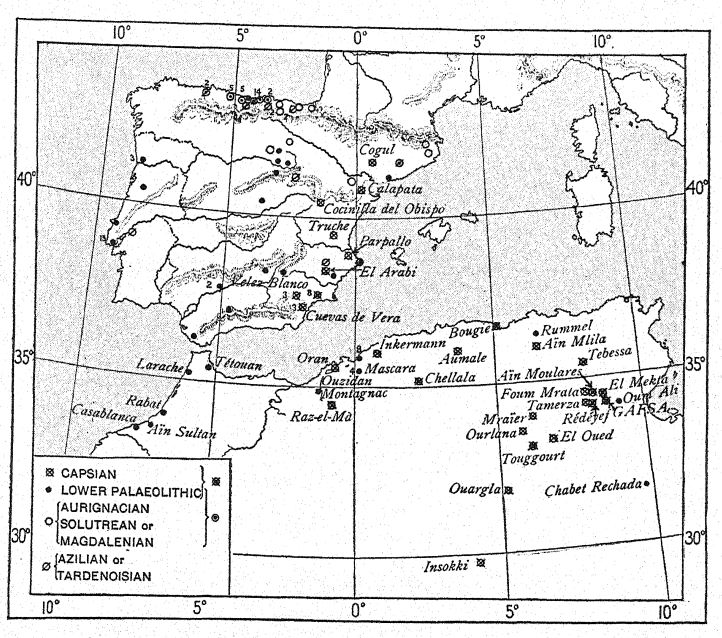

The flint workers of Lower and Upper Palaeolithic times who inhabited the existing geographic regions of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunis sought the flint-bearing limestones for the manufacture of their implements and fashioned them into forms which are closely similar to those found in Spain and France. As a result of the explorations of J. de Morgan, L. Capitan, and P. Boudy between 1907 and 1909[10] it appears that Pakeolithic man in Africa became acquainted with fewer types of implements than his contemporaries in Europe. It is true that we find the Lower Palaeolithic represented by typical Chellean coups de poing, and there were also true Acheulean implements and true Mousterian implements marking the close of Lower Palaeolithic time.

As to the great antiquity of man in these regions, it appears likely that there was a kind of pre-Chellean industry at Gafsa, as at St. Acheul in France, with flakes roughly adapted to the functions of racloirs, points, knives, etc. It is, in fact, very possible so to interpret the very coarse flakes found by Boudy in such abundance in the lower deposits of hill 328 at Gafsa. The Chellean and then the Acheulean culture would have succeeded to this earliest stage, being characterized by an industry strikingly similar for these two epochs. The Mousterian, with its predominance of racloirs, points, and discs, appears in Tunis to have been only a modality, a stage of the great Chelleo-Mousterian period, just as it was in Europe.

Then follows the Aurignacian, the first stage of the Upper Palaeolithic cultures, in which the forms of the flints are, in the opinion of Capitan, extremely similar to those of the Lower Aurignacian of northern Spain and of France. It was at this time, it is believed, that the great wave of industrial migration and perhaps the men of the Crô-Magnon race passed from these northwestern African stations into Spain and France; for it has been noted that the Lower Aurignacian of western Europe comes from the south and not from the east of Europe. The flint-making stations during the long Lower Palaeolithic are widely distributed, as indicated by the black dots of the accompanying map (Fig. 270).

[ p. 515 ]

But now a very important change occurs, as indicated in the stations marked by a crossed circle, in the genesis of new modes of fashioning the in -s which are for a long time peculiar to this region and which — centring in the stations crowded around Gafsa in the heart of Tunis — receive the name of CAPSIAN.

Africa . — At Mostaganem (8) are the eight stations of Aboukir,Ain-bou-Brahim,Karouba, Ouled Zerifa, Ain-el-Bahr, Oued Alelah, Oued Ria, and Alazouna. Near Mascara are the sites of Ain-Hadjar, Ain-Ksibia, Palikao, and Ain-Harca.

Spain . — At V^lez Blanco are the three stations of Ambrosio, Cueva Chiquita de los Treinta, and Fuente de los Molinos; at the Cuevas de Vera are the three caves known as Serrón, Zajara, and Humosa; while the figure 8 marks the eight caves of Paloniarico, Las Perneras, Bermeja, Las Palomas, Tazona, Ahumada, Cueva de los Tollos, and Cueva del Tesoro. Only the Capsian stations of Spain are named here. For the names of others see Fig. 272, p. 519.

The explanation of the life and art of the Capsian is probably that of a climatic change in this region of Africa from a moist and semiforested condition favorable to the larger kinds of game to an arid condition in which [ p. 516 ] the larger kinds of game became less numerous and the chase was abandoned. This is Capitan^s opinion, that the Capsian corresponds to new climatic conditions in northern Africa; for in the depths of the limestone caves it appears that men food parth^ consisted of the animals of the chase, but more commonly of edible land snails belonging to species still existing in this region and occurring in great abundance during the winter and spring rains. This change of climate came after the close of Mousterian time, namely, the period which we estimated (p. 281) at about 25,000 years B. C. on the theory that the Fourth Glaciation closed not less than 25,000 years ago (p. 41).

LOWER PALEOLITHIC OE AFRICA

When we consider that the genuine Chellean industry is completely lacking in central Europe[11] we are driven to the conclusion that this industry came to France and England not from the east but from Africa in the south. Therefore it becomes clear why, in passing to the aforesaid countries from northern Africa, this industry was more widely distributed in Spain than in Italy. Without doubt the same conditions of migration prevailed throughout the entire Lower Palaeolithic. The Acheulean and Mousterian industries followed the same route, for both are typically represented in northern Africa and there is no convincing evidence of these industries having followed any different course.

THE CAPSIAN — UPPER AND LOWER

The succeeding Aurignacian industry of the Mediterranean also had its centre of dispersion in the northwestern part of Africa — a centre known through the labors of de Morgan, Gapitan, and Boudy, and, more recently, through those of Pailary, Gobert, and Breuil. Obermaier regards the Lower Capsian as presenting an industry containing only the Lower Aurignacian (types of Chiteiperron) and Upper Aurignacian (types of La Gravette) and considers that the Middle Aurignacian is wanting in northern Africa. This Middle Aurignacian culture is regarded as of French origin, having apparently extended southward only in the Cantabrian region, where it is typically represented at Castillo, Hornos de la Peña, and the Cueva del Conde.

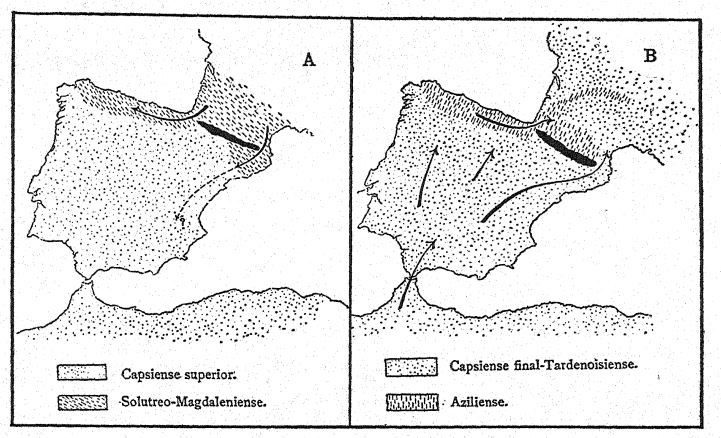

The Upper Capsian, then, is regarded as extending from Post-Aurlgnacian time through the entire epoch of the Solutrean and the Magdalenian of western Europe. Thus for a very long period of time there was no contact whatever between the industry of northwestern Africa and of southwestern Europe. During this period the Capsian itself developed [ p. 517 ] its peculiar forms, and toward the close of the Upper Palaeolithic this industry spread into Spain as indicated by the dotted area and arrows in the accompanying map (Fig. 27 i , J 5 ).

In the development of the Capsian Itself[12] it is found that the iiv dus try varies according to the sites, each with its own evolution of types. For example, at the rock shelter of El Mekta flint knives with blunted backs were of large size, probably because they were used to cut the flesh of game. At Sidi-Mansour, on the contrary, the dwellers, being snaileaters, used only blades as fine as needles and of a type found also at El Mekta, but fewer in number. This, then, is the origin of the microliihic flints which were first discovered at the station of Fere-en-Tardenois, in France, and hence received the name of Tardenoisian. If the conclusions of de Morgan, Capitan, and Boudy are well founded, the Upper Capsian industry of Africa is the true parent of the Tardenoisian of France.

A. Solutrean and Magdalenian industries from France.

B. Late Capsian (Tardenoisian) industry from Africa. After Obermaier.

On the other hand, the identity of tht Lower Capsian with the Aurignacian in Europe is strongly insisted upon by the same authors. The Lower Capsian is a Tunisian phase of the Aurignacian of Europe and absolutely identical with it. The forms from the rock shelters of Redeyef, Foum-el-Maza, and, above all, El Mekta are absolutely typical. In the latter station occur, moreover, forms closely paralleling those distinctive of the Aurignacian of Europe, Lower, Middle, and Upper — the great picks; the large flakes finely retouched; the long, fine blades retouched on one or both sides, often curved, with blunted backs; the notched blades; the [ p. 518 ] nuclei with edges worked into grattoirs; and, above all, the blades with square-edged grattoirs across the ends, often presenting a lateral burin, so characteristic of the Aurignacian. Thus these authors conclude that human evolution and probably the human stock in Tunis was uniform with that of Europe throughout all Aurignacian time until its very close, and that, following this, an independent evolution in North Africa took place.

Little is known of the anatomy of these Lower Capsian vrorkmen. In an abri about two kilometres from Redeyef, and associated with a flint industry characteristic of the Lower Capsian, there were found numerous fragments of human bones much altered, friable, and with very irregular surfaces. Recognizable among this skeletal debris were a decidedly thick cranial vault, and portions of two large thigh-bones (femora) and of shinbones (tibias) which are also thick and very much flattened (platycnaemic). It is interesting to recall that the abundant skeletal remains found at Grimaldi were chiefly of the well-known Crô-Magnon type 'with markedly platycnaemic tibias, and were associated with flint implements characteristic of the Aurignacian culture, which Capitan considers identical with the Lower Capsian.

| INDUSTRIES OF NORTH AFRICA | GEOGRAPHIC CONDITIONS | INDUSTRIES OF EUROPE |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Capsian (Late Upper Palaeolithic) (final phase of Capsian = Tardenoisian) | Reunion with Spain and France | Close of the Upper Pakeolithic Tardenoisian and Azilian Stages |

| (Middle Upper Palaeolithic) | Separation from Spain and France | Solutrean and Magdalenian Stages |

| Lower Capsian (Beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic) | Union with Spain and France | Aurignacian Stage |

| Lower Palaeolithic Mousterian, Acheulean, and Chellean Stages | Union with Spain and France | Lower Palreolithic Mousterian, Acheulean, and Chellean Stages |

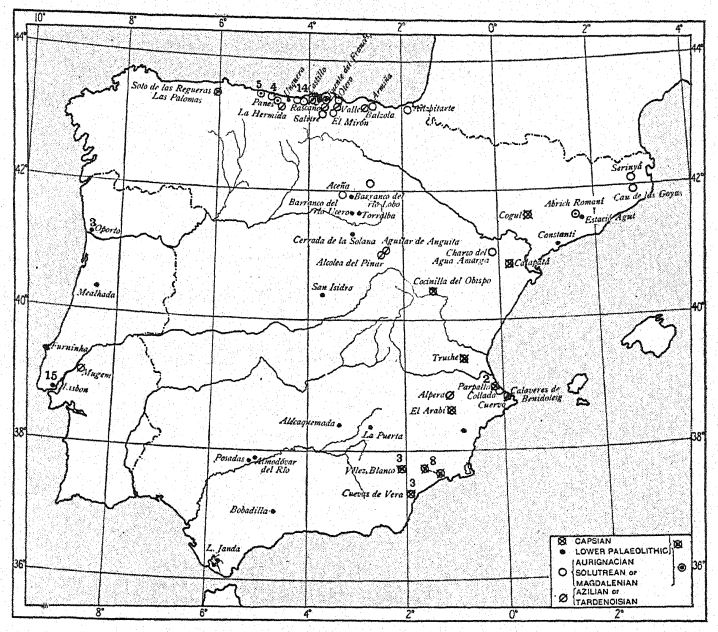

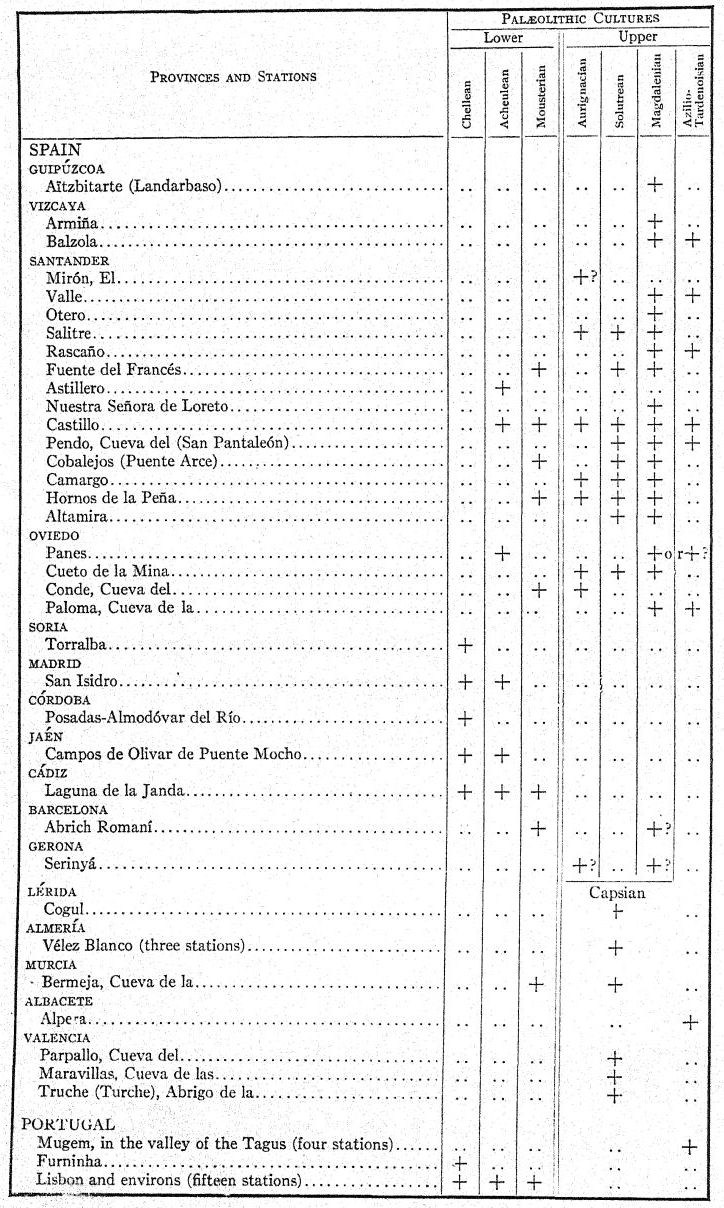

PALAEOLITHIC HISTORY OF SPAIN

Having now considered northern Africa, it is interesting to look at Spain as influenced by Africa on the south, by the industrial and artistic life of France on. the north, and as having an important independent evo^ lution of its own. These conditions are fully described in Hugo Obermaier’s recent work, El Hombre fósil[13] to wiich the reader is referred. Over eighty Palaeolithic stations have been discovered in Spain. Siiain shares with the greater part of Africa (including Egypt), with Syria, Mesopotamia, and parts of India, the extraordinarily wide distribution of industries [ p. 519 ] resembling those of the three Lower Palaeolithic stages — the Chellean, the Acheiilean, and the Mousterian.

North. — 5, Cueva del Conde, Cueva del Río, Collubil, Viesca, La Cuevona; 4, Cueto de la Mina, Balmori, Arnero, Fonfría; 14 (also marked Castillo’), four symbols represent the fourteen closely grouped stations of Castillo, Altamira, Hornos de la Peña, Camargo, Cueva del Mar, Truchiro, Astillero, Nuestra Señora de Loreto, Villanueva, Pendo, Cobalejos, San Felices de Buelna, Peña de Carranceja, and El Cuco. A little west of Fuente del Frances is San Vitores.

West. — At Oporto are the three stations of Pafos, Ervilha, and Castello do Queijo. In or near Lisbon arc the fifteen stations of Agonia, Alto do Duque, Amoreira, Bica, Boticaria, Casal da Serra, Casal das Osgas, Casal do Monte, Estrada de AgudaQueluz, Leiria, Moinho das Cruzes, Pedreiras, Peñas Alvas, Rabicha, and Serra de Monsanto.

Southeast . — At Velez Blanco are the three stations of Ambrosio, Cueva Chiquita de los Treinta, and Fuente de los Molinos; at the Cuevas de Vera are the three caves known as Serrón, Zajara, and Humosa; while between the two sites marked 8 are the eight caves of Palomarico, Las Perneras, Bermeja, Las Palomas, Tazona, Ahumada, Cueva de los Tollos, and Cueva del Tesoro.

By what types of man these industries were pursued in these different countries it would be premature to say. At the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic a profound change occurs, for in the Aurignacian industry we have to do with a Mediterraneo-European culture exhibiting advances in technique which are not developed elsewhere.

[ p. 520 ]

IMPORTANT PALAEOLITHIC SITES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

[ p. 521 ]

At the close of Upper Aurignacian time the community of culture ceases in Spain itself, and this country divides sharply into two regions, northern and southern.

In the northern itgion we observe a close similarity with the Industrial evolution of Frahce during the entire period of Solutreo-Magdalenian time, rhe true Solutrean extended from France throughout the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula. In Cantabria, Early Solutrean is represented by laurel-leaf points found at Castillo, Hornos de la Peña, and elsewhere; while Late Solutrean types— shouldered points, and laurel-leaf and willowleaf points with concave base — appear at Altamira, Camargo, and the Cueva del Conde. True Solutrean strata have not yet been discovered in the east of Spain, although the discovery— made by H. Breuil — of a willow-leaf point at El Arabi would seem to indicate that there may have been some slight infiltration of the Solutrean along the seacoast. Implements suggesting the Solutrean found in Almería (Cueva Chiquita de los Treinta) and Murcia (Cueva de las Perneras) are doubtful, as it is very possible that they represent Neolithic types. The true Magdalenian appears also to be an intrusion restricted to the northern part of the peninsula. It is found in the east in the provinces of Gerona and Barcelona, but occurs chiefly in the Whole Cantabrian region. The homogeneity of the Magdalenian in these parts with that of France is very marked, not only in the Stratification and types of Palaeolithic implements but also in the objects of mobiliary art.

SOUTHERN AND EASTERN SPAIN — THE CAPSTAN

At the same time the southern and eastern regions of Spain were completely under the influence of the Upper Capsian industry of northern Africa and in these regions the typical forms of the Lower Capsian ( = Lower and Upper Aurignacian) tend to become reduced in size and to evolve toward the geometric forms until they finally acquire the aspect of the Tardenoisian microliths. Thus wt find that in the Upper Capsian of eastern and southern Spain, as in northern Africa, true Solutrean and Magdalenian implements are unknown. These implements are replaced by the microlithic industry, chiefly characterized by trapezoidal forms which can be traced eastward along the coast of Africa to Egypt, Phoenicia, and even to the Crimea. A notable part of this industry found its way also into Sicily.

The final phase of the Upper Capsian of Spain is essentially identical with the Tardenoisian of France. Certain discoveries have been made in Guadalajara, in Murcia, and in Albacete (Alpera). To these must be added other Azilio-Tardenoisian stations no less important found in Portugal in the valley of the Tagus. At Mugem and at other stations heaps of sea-shells of a great variety of species prove that when the Upper Capsian men w-ere living they sought the same kinds of food in Spain as in northern [ p. 522 ] Africa. In these heaps the trapezoidal forms of implements predominate, closely similar to those of the Tardenoisian. The animal life of these deposits does not include any sort of domestic animal except the dog.

Of great interest are the numerous burials—chiefly of women and children, more rarely of men— -in which the skeletons occur most often in the folded position. The human type has not been determined, but longheaded (dolichocephalic) skulls greatly predominate, while short-headed (brachycephalic) skulls occur but rarely. It is probable, therefore, that these people belonged to the small, long-headed, dark-skinned Mediterrean race.

Inasmuch as the origins of the Tardenoisian of France are found in the final Capsian stage of Spain, reinforced by African elements, Obermaier regards the Spanish Tardenoisian as somewhat older than the French.

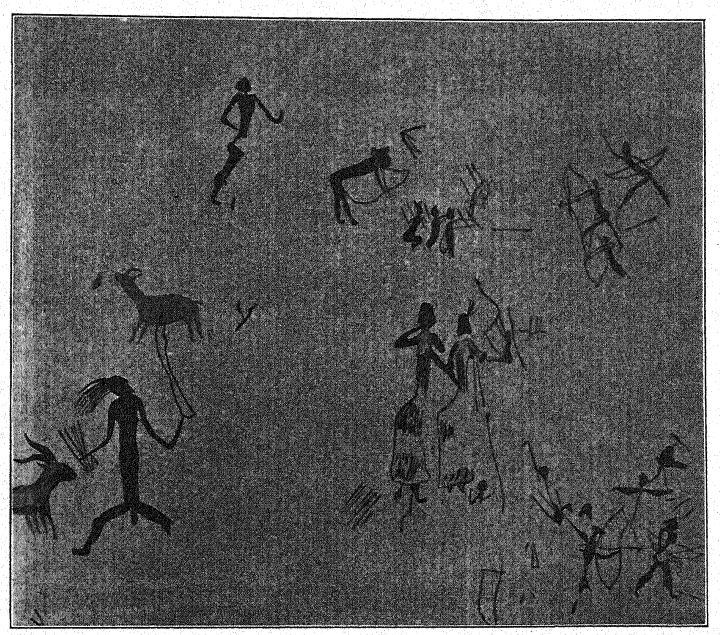

CAPSIAN AND AZILIO-TARDENOISIAN ART

Obermaier observes that it is as yet impossible to determine the period of the commencement of this peculiar art of central and southern Spain, but considers that a transition from the naturalistic art of the Quaternary to the conventionalized schematic art was effected by almost imperceptible degrees. This would imply that no sudden changes took place at this time in the population of Spain, but that the tribes of Upper Capsian culture evolved in situ into the Azilio-Tardenoisian stage, and eventually, owing to the influence of exterior civilizations, into the Neolithic. Final phases of this schematic art contain idols and representations of faces which coincide absolutely with Neolithic idols in the collections of L. Siret, F. de Motos, and others. Moreover, they present similarities to certain designs from the dolmens of the final Neolithic.

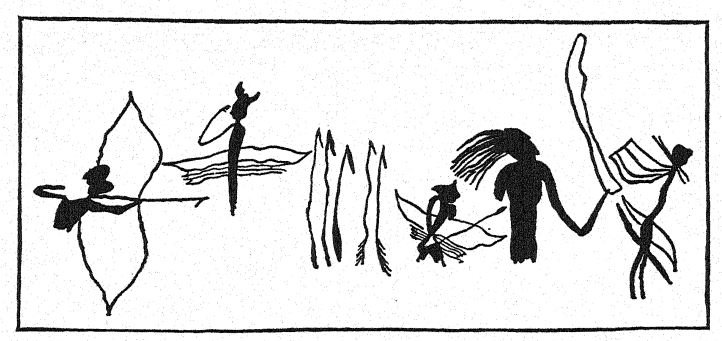

This art is characterized by its numerous reproductions of the human figure. In almost all the important rock shelters of the eastern region (Alpera) it has been possible to distinguish layers of more recent designs painted over the classic Quaternary paintings, and classified— on account of their superposition— as “Post-Palaeolithic.” Of these a small portion are figures still retaining the naturalistic style — representations of animals and men — but poor in conception, stiff and lifeless, in most cases bearing no comparison with the vigor abandon of the figures of Alpera. The greater part of these designs consist of geometric or conventionalized signs or figures.

Still purer in style and more abundant are the instances of this conventionalized mural art in southern Spain, where M. de Góngora, Vilanova, Jiménez de la Espada, González de Linares, M. Gómez Moreno, F. de Motos, H. Breuil, J. Cabre, and E. Hernández-Pacheco have devoted themselves sedulously to its study. Numerous painted rock shelters are known, but almost all without the slightest trace of Paleolithic art and with numerous conventionalized (schematic) petroglyphs, in Andalusia [ p. 523 ] (Velez Blanco, Ronda, and Tarifa) and throughout the Sierra Morena (Fuencaliente). In many cases it would be difficult to guess the derivalon of these designs of human or animal figures, were it not for the existence of gradations in conventionalization from the naturalistic design to the final geometric scheme. With these, arranged in a regular manner, there occur further a great number of ramiform, pectiniform, steliiform, serpentine, and alphabet-like signs, with designs in zigzags, circles, and dots.

Another important centre is found in western Spain (Estremadura) the notable designs of which are mentioned by Lope de Vega in 1597 — doubtless referring to the paintings of Canchal de las Cabras in Las Batuecas.

Slight infiltrations of the same art have been recognized in northern Spain at Castillo, Santander, and at the open station of Peña Tú, near Vidiago, Oviedo. As a notable exception to the naturalistic art prevailing north of the Pyrenees we may mention the paintings in this same geometric style found in the cave of La Vache, near Tarascon, Ariège, in southern France.

[ p. 524 ]

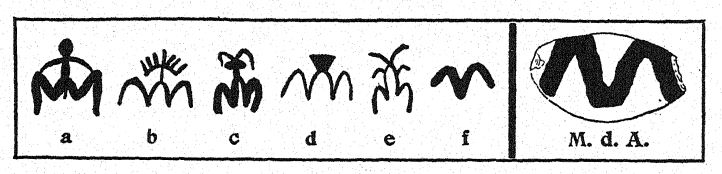

Of equally great interest is the explanation which this art affords of the remarkable painted pebbles of Mas d’Azil which are now seen to be partly pictographic in origin, chiefly schematized representations of the human figure which gradually begin to assume shapes closely resembling those of the Phcenician alphabet. As early as 1912 Henri Breuil was considering this pictographic theory and beginning to refer to the ‘Azilian signs’ at Las Batuecas as reminiscent both of the painted pebbles of Mas d’Azil and of the mural paintings of Andalusia. But chiefly he made clear the importance of the “dotted lines, ramiform, pectiniform, and stelliform signs, zigzags, circles, and figures vaguely resembling alphabetic forms.” A very ingenious study of these schematic Azilian signs has been made by Obermaier in El Hombre fósil, where he endeavors to trace the conventionalized descendants of human figure of the ancient naturalistic style as shown in Fig. 274. The demonstration of this theory may in good time make possible a logical interpretation of a great part of these same painted pebbles of the Azilian. Obermaier feels confident that they should be considered as religious symbols, and that these petroglyphs of Spain will supply a proof that many of the designs on these pebbles plainly show conventionalized human figures.

Some years ago A. B. Cook drew attention to the fact that a native tribe in central Australia, the Arunta, is distinguished by each clan having a deposit of ‘churingas’ in a cave. There the churinga of each individual of the clan, be it man or woman, is the object of vigilant protection. They are made of wood or stone, and in the latter case show a striking resemblance in form and decoration to the Azilian pebbles. The Australian sees in each churinga the incarnation of one of his ancestors, whose spirit has passed to him and whose qualities he has inherited. It is noteworthy that, according to Australian beliefs, they can acquire the gift of speech by means of the ‘bull-roarer,’ an amulet of stone or bone.

By analogy with the preceding, it is possible that some of the Azilian pebbles represent such ‘stones of the ancestors,’ an incarnation of masculine or feminine forefathers whose symbols w^ere the objects of an especial cult. F. .Sarasin found in the cave of Birseck, near Arlesheim, SvdtzerJand, a t3npical Azilian deposit with painted pebbles which had all [ p. 525 ] been intentionally broken, without exception. He advanced the not improbable theory that this evidenced an act of the extremest hostility against the sanctuary of a tribe, performed in order to despoil its members forever of the protection of their ancestors, seeking in this way to subjugate or annihilate them.

In the Capsian silhouettes there is little likeness to the naturalistic art of the Crô-Magnons in the north of Spain and in France. We are reminded rather of the rock paintings of the Bushmen and of the huntingscenes depicted by North American Indians, but on the w^hole there is greater tendency to grouping and composition of standing figures, masculine and feminine, in ceremonies and in the chase. The male figures are mostly nude, and occasionally have head ornaments of feathers; while the female figures are represented with kirtles, head-dresses, and ornaments on the body, arms, and ankles. Masculine figures in the chase are accompanied by hunting-dogs and exhibit the bow and arrow. If these drawings are correctly assigned to the close of the Upper Palaeolithic, this is the most ancient representation of this primitive weapon of the chase of which we have record. The arrow seems to be single-barbed, as shown in the accompanying cut from Alpera. It may have been pointed with flint fastened on one side to the shaft. We recall that double-barbed arrow-heads were in use in Magdalenian times, as shown in the cavern of Niaux.

¶ Footnotes

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, metrical version by J, M. Good. Bohn’s Classical Library, London, 1890. ↩︎

Bossuet, Jacques Benigne, Discours sur l’Histoire universelle (first published in 1681), pp. 9, 10. Edition conforme ^ celle de 1700, troisieme et demiere Edition revue par Tauteur. Paris, Librairie de Firmin Didot Freres, 1845. ↩︎

The Satires, Epistles and Ars Poetica of Horace, the Latin Text with Conington’s Translation, pp. 29, 31. George Bell & Sons, London, 1904. ↩︎

Aescliylus, Prometheus Bound. Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Poetical Worhs of Elisabeth Barrett Browning, pp. 148, i49- Oxford edition, 1906. Henry Frowde, London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, New York, and Toronto. ↩︎

Kobeit, W., Die Verbreikmg der Tierwelt, pp. 403-7. G. H. Tauchnitz, Leipsic, 1902. ↩︎

Abercromby, Hon. John, The Prehistcric Pottery of the Canary Islands and Its Makers. Royal Anthropological Institute, November 17, 1914. Nature^ December 3, 1914, p. 3S3. ↩︎

- Verneau, Dr. R., Cinq annees de sejour aux ties Canaries. (Ouvrage couronne par TAcademie des sciences, 1891.)

*B unbury, E, H. History of Ancient Geography, voh I, pp. John Murray, London, 1879. ↩︎

Miller, Gerrit S., Jr., The Jaw of the Piltdown Man, Smitlisonian Institution, Washington '^ovember 24, 1915. ↩︎

J. de Morgan, L. Capitan, and P. Boudy, “Stations prehistoriques du sud Tunisien,” Rev. Ecole d’Anthr., 1910, pp. 105-136, 206-221, 267-286, 335-347; 1911, pp. 217-228. ↩︎

Obermaier, Hugo, El Hombre fósil, 1916, p. 203. ↩︎

Obermaier, Hugo, El Hombre fósil, 1916, pp. 346, 347. ↩︎

Obermaier, Hugo, El Hombre fósil, 1916. ↩︎