[ p. 258 ]

Thanks be to Allah! whatever my heart yearned for,

Has, at last, appeared from behind the curtain of fate.

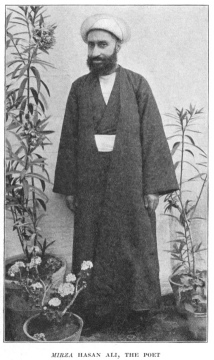

Upon returning to our lodging, I was visited by Mirza Hasan Ali, a relative of mine, who greeted me with the utmost respect and warmth. I would mention that he himself is a poet of no mean qualities, and also a learned historian; but, alas! to-day, in Iran, His Majesty is too much busied with the affairs not only of his own empire but also of every corner of the world, where his royal representatives reside, to be able to reward his poets. Indeed, when I tell you that Mirza Hasan Ali scarcely ever writes poetry, but is occupied in trying to make money out of a coal mine, where many men have already lost their fortunes, you will understand that the times have clashed together.

I was much pleased, however, to make the acquaintance of a kinsman, whom I had heard of for many years, and who I now learned had the peculiarity of never finishing the house he lived in, for fear that, once the house was completed, he would die.

[ p. 259 ]

[ p. 260 ]

[ p. 261 ]

But I must not forget that my readers are anxious for a description of some other of the magnificent buildings of the Sacred Threshold, and so I will ask them to accompany me to the “New Court.” This splendid edifice was commenced by Fath Ali Shah of the Kajar dynasty, and was enriched by Nasir-u-Din Shah, may Allah pardon him!

The portico leading to the Shrine is termed the “Nasiri Golden Porch” in honour of the great Shah, Nasir-u-Din, who paved it with beautiful marble, and covered the walls with golden tiles which dazzle the eyes.

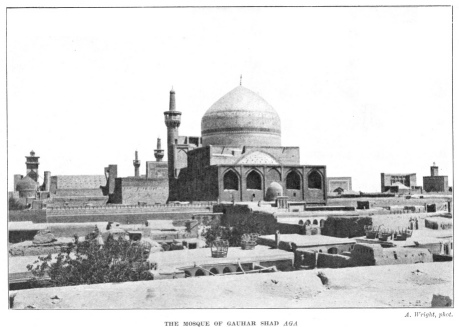

After the Shrine there is nothing in Meshed which can be compared with the mosque of Gauhar Shad Aga, who was, as has been already mentioned, the wife of Shah Rukh, son of dread Amir Timur, Lord of the Conjunction of the Planets.

In the centre of the noble quadrangle is the unroofed mosque of the “Old Woman.” The story runs that when Gauhar Shad Aga, may Allah forgive her, wished to purchase the land in order to erect the mosque thereon, an old woman refused to sell one plot, but demanded [262] that on it should be built a separate mosque bearing her name. So great was the love of justice of the Princess that her petition was agreed to, and thereby two women have obtained undying fame, the one for her piety and the other for her justice.

Now, O ye wise men of Europe, what is better than justice, and what monarchs can the world produce to compare with Faridun, of whom the poet wrote:

Faridun the noble was not an angel;

He was not formed of musk and ambergris.

From justice and generosity he obtained his reputation.

Do thou justice and show generosity, thou art Faridun.

This same monarch bequeathed the following advice to his descendants as a priceless legacy:

Deem every day in thy life as a leaf in thy history;

Be careful, therefore, that nothing be written in it unworthy of posterity.

A nobler maxim than this no one has heard. But Faridun was not the only monarch of Iran renowned for justice throughout the Seven Climates. For it is narrated that Omar, who was subsequently second Caliph, and Muavia, who was the first monarch of the Omayyad dynasty, visited Madain, then the capital of Iran, during the reign of Noshirwan. One of the King’s sons wished to purchase a mare belonging to them, but they refused to sell it at any price, and, ultimately, it was forcibly taken from them by the servants of the prince.

[ p. 263 ]

A. Wright, phot.

[ p. 264 ]

[ p. 265 ]

The strangers complained to Noshirwan, who inquired into the case, and finding their complaint to be well founded, the mare was returned to them with rich gifts from the king.

Upon leaving the city on their return journey they saw the corpse of a quartered man on the gate; and asking for what crime this sentence had been passed, were informed that the corpse was that of one of the King’s sons who had taken a mare by force from some strangers.

Many years passed, the kingdom of Persia had fallen into the hands of the Arabs, and Muavia was Governor of Syria. There he behaved in a tyrannical manner, and seized some property unjustly. Complaint was made to Omar, who was now the Caliph, and he, finding that the charge was true, wrote to Muavia a letter of one word, and that word was “mare.”

The wretched man was preaching the Friday sermon in the mosque of Damascus when the epistle was delivered, and on reading it he fainted and nearly died from fear; and when he recovered consciousness he immediately restored tenfold what he had taken by force. Thus was the justice of Noshirwan a shining light to the Seven Climates, and, moreover, there is a tradition to the effect that the Prophet, on him [266] be Peace, considered that his own birth during the reign of so just a monarch was auspicious.

To resume, there are four porches in the mosque of Gauhar Shad Aga, which are considered to be unsurpassed for elegance of construction, for loftiness, and for perfection of proportion. The tilework, too, is so beautiful that how can I represent it?

In the Aiwan-i-Maksura, above which rises the superb blue dome, stands an exquisitely carved wooden pulpit of especial sanctity, as, when the Day of Judgment is at hand, the twelfth Imam will descend on to it. May Allah hasten his advent; and may He grant that we may ever keep the Day of Judgment in remembrance!

But before quitting the Sacred Threshold I would refer to Allah Verdi Khan, who is honoured by being buried in a building adjoining the haram. This individual was a noted general of Shah Abbas, and ordered his tomb to be built during his lifetime. When it was completed the architect came to him, settled the account, and then said, “The dome is completed and only awaits Your Excellency’s august body.” The great noble considered this to be a message from Allah the Omnipotent, and four days after hearing it he expired.

I will now refer briefly to the famous colleges [267] of Meshed, sixteen in number. In each of them students are provided by the legacies of pious men, not only with spiritual and intellectual knowledge, but even with food and, in some cases, with clothing.

In these colleges there are twelve hundred students, not only from every province of Persia, but also from distant India and still more distant Tibet.

Each student attends classes beginning with syntax and ending with jurisprudence, theology, and philosophy. This course, which is termed “superficial,” lasts nine years, after which the student proceeds to Najaf, where for a second period of similar length he attends the lectures of the famous doctors of law.

Finally, when considered sufficiently instructed, he receives a written certificate, sealed by the principal doctors of law, to the effect that he has acquired learning equal to their own, and is a fit interpreter of the law, in which it is no longer lawful for him to follow the opinion of another. He then returns to his home, where he speedily acquires a good practice.

Among these colleges is one situated in the “Upper Avenue,” which was endowed by a certain Fazil Khan, who acquired his wealth in India. One of the conditions he left in the deed of endowment was that neither Indians, [ p. 268 ] Mazanderanis, nor Arabs were to be admitted. Indians because they were miserly, Mazanderanis because they were quarrelsome, and Arabs because they were dirty and unmannerly.

It is stated that an Arab applied for admittance, and upon learning the reason why he was excluded, exclaimed, “May Allah bless thy father, O Fazil Khan, for thou hast spoken the truth!”

Yet another college was endowed by a Persian, who gained his wealth in a remarkable manner. One day a rich merchant asked him whether he was willing to work at a place to which he would be conducted blindfold. Being a fearless Kermani and very poor he agreed, and was led through many streets to a courtyard where the bandage was removed, and he was ordered to dig a hole and bury gold coins and jewellery. This he did for several days, and being searched before he left, he saw no chance of bettering his condition.

However, one day he saw a cat, which he killed and ripped open. He then sewed up some money and jewels inside it and threw it over the wall. After this, when his work was done, he wandered about until he found the cat, and not only secured the money hidden in its body, but also learned the position of the house.

Its owner shortly afterwards died, and the astute Kermani bought his house with the gold [269] sewn up inside the cat, and as the merchant had never revealed his secret to any one he became his heir, and in turn, when dying, bequeathed his money for the pious task of founding and maintaining a college. May Allah pardon him!

More than one of these colleges, these seats of the deepest learning, were visited by me, and when I saw the eager students gathered round wise, white-bearded professors, and listened to the wisdom that flowed like honey from those learned lips, I thanked Allah that he had ordained Meshed to be a “Lamp of Guidance.”

After visiting all the centres of sacred interest, Mirza Hasan Ali agreed one day to guide me to the tomb of Firdausi at Tus, as it would not have been befitting for me to leave Khorasan without first honouring myself by such a visit.

Tus is situated some four farsakhs from Meshed by the Kashaf River, and, even from a long way off, its ancient walls and towers were most conspicuous. Approaching the ancient city we descended to the banks of the river, and crossed it by the famous bridge which is connected with the great poet.

As I have previously mentioned, Sultan Mahmud treated Firdausi with great miserliness; but, some years later, he was riding with his Vizier, and the question turned on whether a [270] certain chief would submit or have to be attacked. The Vizier, by way of answer, quoted:

And should the reply with my wish not accord,

Then Afrasiab’s field, and the mace, and the sword!

“Whose verse was that?” inquired the monarch, and, on learning that it was by Firdausi, he repented of his lack of generosity, and sent him a rich gift carried by the royal camels, together with an expression of his regret. But, as the camels entered the city, they met the bier on which Firdausi was being borne to his tomb!

Passing through the ruined walls we hastened on, and at last Mirza Hasan Ali pointed me out the spot where the poet lies. But, alas for the honour of us Iranis! there was no dome to mark where Firdausi, the glory of Iran, was buried, and not even a tombstone.

Allah knows how I wept for the disgrace which I, as a poet, felt most keenly, and how I repeated his poems throughout the heat of the day, and more especially the lines:

All had been dead for ages past;

But were restored to life by my poetry:

I, like Jesus, have infused life

Into all of them with my verse.

Inhabited buildings will be ruined

By rain and the revolution of the Sun:

I, however, with my poetry have reared a noble edifice

That neither wind nor rain can harm. [p. 271 ]

This poem will pass through many cycles:

And all those who possess wisdom will read it.

I have undergone many hardships during thirty years,

But have brought Persia back to life with my Persian [^68] poetry.

At length, wearied out by the journey and my emotions, I fell asleep, and, in a dream, I beheld Firdausi writing his poem. Looking more closely, I saw that the poet was engaged in writing the famous story of the sons of Faridun.

It is related that when that illustrious monarch became old he gave his eldest son, Salm, the west, and Turan or Tartary to Tur; but on his youngest, Erij by name, he bestowed Iran. The two elder brothers threatened to revolt on hearing that Iran, their home and the seat of royalty, was to pass to the youngest member of the family, and Faridun was distraught at thus ending his glorious reign.

However, Erij, who was the noble son of a noble sire, heard what was the cause of his aged father’s grief, and, visiting his brothers, offered to resign his crown rather than that there should be civil war. But Salm and Tur, whose mother was a daughter of Zohak, the accursed, conspired together and decided to put Erij to death.

While I gazed I saw that an angel was [272] guiding Firdausi’s pen, as he wrote the appeal of Erij to his brothers:

Will ye ever let it be recorded

That ye, possessing life, deprive others of that blessing?

Pain not the ant that drags the grain along the ground;

It has life, and life is sweet and pleasant to all who possess it.

Scarcely had the last word been written than I awoke and behold it was a dream, but I fell down prostrate on the ground and thanked Allah the Omnipotent that on me, a humble poet of modern Iran, such a signal blessing had been conferred.

My last visit to the Shrine was at night, and, upon the whole, I was pleased that it was lighted with the electric light, which is, at any rate, free from objectionable matters, foreign candles being, they say, made of even the fat of the unclean animal. [^69]

But yet I yearned to be back in the days of Shah Abbas, who, after having performed the entire journey from Isfahan on foot, undertook the menial task of trimming the locally made candles, thousands of which illuminated the Shrine. On this occasion His Majesty was attended by Shaykh Behai, who composed the following quatrain:—

The angels from the high heavens gather like moths

O’er the candles lighted in this Paradise-like tomb:

O trimmer, manipulate the scissors with care,

Or else thou mayest clip the wings of Gabriel.

[ p. 273 ]

Major Sykes, phot.

[ p. 274 ]

[ p. 275 ]

I have not, O inhabitants of Europe, described to you the fort with its palaces, where a princely Governor-General dispenses justice and maintains such order that Khorasan is as tranquil as Kerman; nor have I described in detail the other buildings which adjoin the Shrine, for any allusion to them would, as we say, be like taking the foot of an ant into the presence of Solomon.

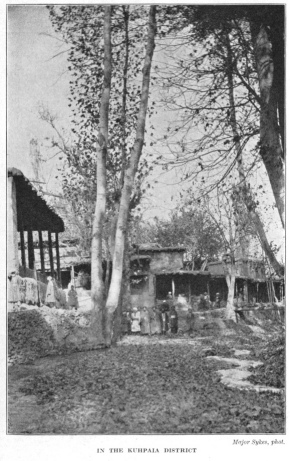

We had now completed our pilgrimage and had visited everything which it was right and proper to visit. We had even spent some days in the cool country of Kuhpaia, where the beautiful gardens and the running streams surpass description. In short, there was no reason for remaining any longer.

And yearning to return to Kerman took such a hold upon Ali Khan that he kept repeating:

On Friday night I started from Kerman;

I did wrong as I turned my back on my friend.

Indeed, we were all equally affected, and I quoted the verses which Rudagi sang at Herat to the home-sick Amir Nasr ibn Ahmad:

The sands of Oxus, toilsome though they be,

Beneath my feet were soft as silk to me.

Glad at the friend’s return, the Oxus deep

Up to our girths in laughing waves shall leap.

Long live Bokhara! Be thou of good cheer!

Joyous towards thee hasteth our Amir! [p. 276 ]

The Moon’s the Prince, Bokhara is the sky,

O sky, the Moon will light thee by-and-by!

Bokhara is the mead, the Cypress he,

Receive, at last, O mead, the Cypress tree!

No poem, perhaps, ever produced such sudden effect, as the Amir leaped on to the saddled horse, which was always kept ready for an emergency, without even donning his boots, and left his astonished courtiers to follow as best they might.

We too felt that the sands of the Lut would be softer than silk, but not in the least toilsome to pilgrims returning home from Sacred Meshed, and soon we began to make preparations for our return.

We had started on the pilgrimage in the spring time, and we left Meshed, on our return journey, at the end of the “Forty days of Heat”; and, Alhamdulillah! two months later we reached Baghin, which is but one stage from Kerman.

There we were met by many of our nearest relations and oldest friends, and Rustam Beg brought the Arab horse with the golden trappings for me to ride.

The next day, at about a, farsakh out we were met by half the city, who congratulated us so warmly and so lovingly, that, bursting into tears, I said, "Allah is my witness that Shah [ p. 277 ] Namat Ullah wrote the truth when he composed the lines that “We are men of heart.”

Escorted by relations and friends our joyous party entered the city and passed through the bazaars, where all the shopkeepers rose up in our honour, and so to my house. Now my house is by no means small, but when I represent that there was no room for people to stand even in the courtyard, I have explained the matter.

At last my relations and friends had wished me “May Allah protect thee,” and, tired out with the long journey and my reception upon returning home, I retired to rest. But before sleep like that of the Seven Sleepers overtook me, a voice from The Unknown reached my ears, a voice of such mellifluous sweetness that its very tones brought repose to my mind. Thrice it thrilled me with the words, “Thy pilgrimage is accepted,” and by the grace of the Imam, to him be praise, peace, perfect and infinite, filled my soul.

Tamam Shud,