[ p. 65 ]

Now when once more the Night’s ambrosial dusk

Upon the skirts of Day had poured its musk,

In sleep an angel caused him to behold

The heavenly gardens’ radiancy untold,

Whose wide expanse, shadowed by lofty trees,

Was cheerful as the heart fulfilled of ease.

Each flow’ret in itself a garden seemed,

Each rosy petal like a lantern gleamed.

Each glade reflects, like some sky-scanning eye,

A heavenly mansion from the azure sky.

Like brightest emeralds its grasses grow,

While its effulgence doth no limit know.

Goblet in hand, each blossom of the dale

Drinks to the music of the nightingale.

Celestial harps melodious songs upraise,

While cooing ring-doves utter hymns of praise.

Nizami’s Laila and Majnun

One day my uncle spoke to me with great kindness, and said that, as I was fully eighteen years of age, it was time that I thought of marriage. He then advised me not to prize beauty alone; but rather to hope for a modest, pious, capable woman, who would speak little, but who would be economical, discreet, and prudent. “If thou [66] marriest such a woman,” he cried, “she will be the prop and stay of thy existence.”

On the other hand, said he, as Shaykh Sadi wrote:

A bad woman in the house of a virtuous man is his hell, even in this world.

Save us, O Lord, from this fiery trial!

My uncle finally quoted from the Sayings of the Prophet, “Second only to the benefit of believing the faith of Islam, is that of marrying a Mussulman wife, who rejoices the eyes of a man, obeys his wishes, and, during his absence, watches faithfully over his house and possessions.”

Upon hearing these words I was deeply moved, and was only able to reply:

What objection can a servant raise?

It is for the Master to command.

I then went off to the women’s apartments, where my mother greeted me with a significant smile; and I soon understood that she had been the instigator in this plot and that she had already been busy for some time in arranging a marriage for me.

You do not perhaps know that, when a mother considers it time for her son to marry, she makes inquiries in every direction, by means of special agents who are generally old women, and when they hear of a girl who is handsome, [67] of a docile disposition, and of suitable family, she and a friend call upon her mother, who, when the subject is first broached, makes excuses, such as that the girl has been dedicated to a Sayyid. [1]

This, however, is merely to show that there is no undue haste, and, when the girl is asked to bring sugar and water, the object of the visit is formally announced. The girl retires, adorns herself, and then brings in water, which she presents to the visitors, who embrace her and examine her very closely.

A long consultation, in which the girl has no part, now takes place, and all details are given on both sides, with much exaggeration, as to the character, qualities, and position of both the young people; and the meeting is finally brought to a close by sweetmeats being handed round.

After this, ingenuity is exercised by the women to gain a view of the proposed bridegroom, which is not difficult, as he can easily be seen riding or walking. For the youth to see his future bride is, however, quite incorrect; but yet my mother had even arranged this. She had, after the first meeting, discussed the matter with her relations and friends, who knew both families and had again visited the house, [68] and asked for sweetmeats, which is tantamount to stating that her side had agreed to the match. She also had arranged for a return visit to be paid by the girl’s mother and my future bride, whose very name Shirin expressed sweetness, but who was ignorant of what was being settled.

One day my mother informed me that they would pay their visit that afternoon, and that the girl would be seated in the lowest place in the party opposite the door. She added, “If you were to look into the room through a chink at that time, remember it would be most improper, and I should speak severely to you if I saw you.” My mother again smiled and, as I understood her meaning, my emotions were so overpowering that I almost fainted.

Allah knows what trouble I gave at the bath that day and how carefully I donned my best clothes, and how rakishly I placed a new kolah [2] on my head; but, even so, I was ready long before the ladies came, and in my lovesick condition I kept repeating “Shirin! Shirin!”

Say nought of the lusciousness candy contains, e’en sugar unmentioned may be;

For all, save the sugar possessed by thy lips, is wanting in savour to me.

At last, two hours before sunset, I saw from [69] my hiding-place five ladies arrive. The leading one was, I felt sure, my future mother-in-law, who, I had been told, would be accompanied by her sister. Then came a form which, in spite of the dark blue outer robe and white veil, I saw was like a cypress, with the gait of a pheasant; and my heart revealed to me that it was my beloved. Two confidential female servants completed the party.

I knew that if I looked into the room too I soon the ladies would not have removed their outer robes or veils; so I contained myself for a quarter of an hour, although it seemed to me like a year.

At last, trembling like a willow branch, I quickly entered the women’s apartments, and, hardly knowing what I did, instead of looking through the chink, I opened the door. As I did so, I met for one second the gaze of a houri with eyes like those of a gazelle, under eyebrows resembling a crescent moon. More than this I saw not, as a cry was raised and my beloved wrapped her robe round her and fled out of the room.

My mother and the other ladies then asked me how I dared to enter an assembly of women, and I stood abashed for a minute and then shut the door, and as if in a dream retired to my room where my heart, wounded by the darts from [70] those eyes, kept me awake for the whole night, crying and tossing from side to side.

Tell sleep not to enter my eyes any more,

Because the island which was thy abode has been submerged in water.

However, my mother and uncle were, all the time, working in my interests, and informed me that they had agreed that the bride should be given one-sixth of the village of Sar Asiab and one thousand tomans as a dowry, half of which was to be paid in cash before and half after the marriage; also an agreement was made that the bride should never leave Kerman against her will. Indeed, the details of the agreement were so numerous that I cannot describe them.

A few weeks later the betrothal took place. In the morning six large trays containing a fine Kerman shawl, a ring set with diamonds, a pair of gold earrings and much sugar, tea, and sweetmeats were sent to the bride’s house. My Shirin was then adorned and the earrings were placed in her ears by a lady of distinction, who was blessed with a family of eighteen children, of whom fourteen were sons. General rejoicings then ensued, which, however, only the ladies of both families attended; and it may be understood how I yearned for the marriage to take place, although I now understand fully that such an important event should be carried out with due [71] delay so as to enhance the dignity of the proceedings.

Then, however, I was, I fear, ill-tempered and peevish, and could only compose verses which I thought poor, but which are now held to be worth ten gold pieces a line, such as

O Spring Cloud, discharge abundantly in the vineyard;

If a drop of rain become wine why should it be wasted in forming a pearl? [3]

Or again my famous verse, in which the four elements are mentioned:

When the morning breeze lifted the veil from thy face,

It smote to the earth the honour possessed by the fire of Zoroaster. [4]

Two months after the engagement the chief astrologer was called into consultation as to the auspicious day for the performance of the marriage ceremony; and, having fixed upon three hours to sunset on the following Wednesday, intimation to this effect was sent to the father of the bride.

On the day, a tray containing one hundred [72] different varieties of drugs and herbs, with a mirror and ten yards of white sheeting to cover the bride during the ceremony, was sent to her home. The other gifts were two candlesticks, twenty pairs of shoes, and several trays containing sweetmeats. All these matters are regulated by etiquette, so polished and civilised a people are we Persians.

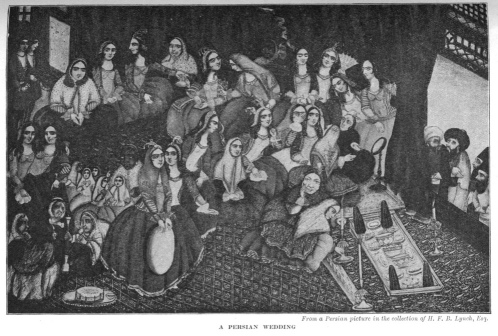

Four hours before sunset, after spending the day at the hammam, during which time my hair and nails were beautifully dyed, we assembled in the great hall at the house of Ali Naki Khan, my future father-in-law, and were greeted by the relations of both families, the ladies, meanwhile, assembling in the women’s apartments.

Shirin, who on the previous day had visited the bath, had been, as she afterwards told me, placed on a saddle facing towards Mecca, with all her garments untied, until the ceremony was completed Opposite my beloved were the mirror and the comb; and, in front of the mirror, the two candlesticks were placed and lighted. The white sheet was draped over her head, and, when she was arrayed in all her wedding garments, my mother said that she resembled Bilkis, that queen of Sheba who visited Solomon the son of David.

Meanwhile her mouth was filled with sweetmeats, and sugar dust was sprinkled over her head by rubbing two pieces together. To increase her good fortune, a lady took a needle, threaded it with a thread made of seven coloured strands, and passed and repassed it through the white sheet which was draped over the head of the bride. This very ancient custom is never omitted. Finally, drugs were thrown into the fire until the atmosphere itself became amorous.

[ p. 73 ]

[ p. 74 ]

[ p. 75 ]

The chief priest of Kerman, Aga Mohamed, who was related to my mother, performed the ceremony. When he took his seat among us, he called me to his presence and asked me if I authorised him to act as my agent. On receiving my reply in the affirmative, he inquired who was the agent on behalf of Shirin, and on hearing that it was Shaykh Abdulla he had the draft of the marriage deed, containing all the conditions, read out three times.

Shaykh Abdulla thereupon proceeded to the curtained door of the women’s apartments when, on his announcing his errand, Shirin, who required much encouragement before she would speak, stated three times that she agreed to the marriage. After this, he returned and informed Aga Mohamed that Shirin had agreed to the marriage. Upon hearing this, the marriage was declared to have taken place; and congratulations were offered by all those present.

At the termination of this ceremony I was [76] taken to the women’s apartments, into the room where Shirin was sitting. She rose up to receive me and, as soon as I had placed nay hand on her head as a token of my protection to her in the future, she tried to place her foot on mine; but I, dexterously avoiding it, gently placed my foot on her foot. This ceremony is necessary, and whoever of the two places his or her foot on the foot of the other, will, we believe, continue to rule for life.

We both saw the faces of each other reflected in the mirror, which had been placed in front of Shirin; but I had to give her a handsome present in the shape of a pearl ring before I could secure to myself the pleasure of seeing her face in the mirror. It may be mentioned that, during the performance of this ceremony, all widows or twice married women, and all unmarried girls, are rigidly excluded from among the ladies sitting round the bride, as their presence is sure to bring bad luck to her.

Soon after the conclusion of the marriage ceremony I grew impatient, and began to trouble my mother with hints that the wedding should take place without delay; but she put me off by saying that the ornaments and other wedding furniture had not yet been completed by the bride’s parents, who had asked for a period of at least two months for these preparations.

[ p. 77 ]

Allah knows how I counted the days and nights; and the moment that this period had elapsed, I again had it conveyed to my mother that she should hasten on the wedding; and I represented that, unless she wished me to become as thin as Majnun, [5] the famous lover, whom even the wild beasts pitied, she must use all her influence and not allow unnecessary delay:

The nearer the time of meeting with the beloved approaches,

The fiercer burns the flame of love.

After declaring, for some days, that such haste was not correct, my mother understood that I was really beginning to waste away; and, fortunately, just about this time, intimation was received from Shirin’s mother that all the wedding furniture had been completed. My mother at once sent again for the chief astrologer, and he fixed on the Friday night [6] as the most auspicious of auspicious times for the consummation of the marriage.

On the afternoon of that day the wedding gifts were sent from the bride’s to my uncle’s house, passing through the principal streets of the city; and men and women thronged in hundreds in the streets and on their roofs to see and admire them.

[ p. 78 ]

All the household furniture, such as cushions, pillows, velvet curtains embroidered in gold, lamps, candlesticks, copper and porcelain utensils, tea and coffee services, and other articles too numerous to mention, were carried on trays; and carpets and boxes of clothes belonging to the bride were borne on gaily caparisoned mules, with bells round their necks and also swinging at their sides; and, with all these things, the rooms set apart for the use of the bride were prepared for her reception.

Feasting had been the order of the day both at my uncle’s house and at the house of Ali Naki Khan for several days; and I had spent part of the Thursday entertaining my friends at a hammam, which had been specially reserved for this purpose; and, after giving gifts to the bath attendants who had shampooed me and dyed my hair and nails, I stepped forth, clad in a suit which my father-in-law had presented to me. This suit included a shirt made by the hand of Shirin from the white sheet which was draped over her head when the marriage ceremony was performed.

At four hours after sunset, my uncle with our male relations and friends, proceeded to the bride’s house, followed at a very short distance by all our female relations, including my mother, and preceded by lighted candles, lamps, [79] torches, and musicians; fireworks too were let off.

The men assembled in the hall, and the ladies were seated in the women’s apartments, and sherbet was served, followed by tea and water pipes. My uncle then presented the completed marriage deed, which had been written out on paper, most beautifully decorated with gold and other colours, to the bride’s father who took it to show to Shirin’s mother.

Meanwhile Shirin, too, had been to the hammam, where her hair and hands and feet were dyed, and her back carefully depilated to remove all traces of hair, as it is believed that there is a hair of the Angel of Death on a woman’s back which, if allowed to remain, would bring ill luck to the family. After her return to the house, she was taken to a special room where her relations dressed her in her bridal clothes and ornaments.

When the bride was ready to start, the men formed themselves into a procession which was followed by a second procession, in which was Shirin, riding on a richly caparisoned Bahrein donkey, and surrounded by ladies of both families, with the exception of her own mother, who remained behind, as also her father. The bride who, at the moment of departure from her home, received some bread, salt, and cheese in a handkerchief [80] handed to her by her youngest brother, was preceded by a man who carried a mirror with its face towards her. On the way she was stopped several times by the ladies of her family demanding gifts, which had to be presented by some prominent members of my uncle’s family.

When the bride approached our house she was made to stop, and the ladies declared that she would not move forward until I myself had appeared. In the meantime I had gone to meet her, and I soon heard the clang of instruments, the noise made by the fireworks, and the hum of many excited voices.

The ladies, upon seeing me, cried out, “We have accepted you!” They added, “You have taken great trouble.” I then turned back ahead of the procession.

When the bridal party reached the entrance of the street, in order to avert the evil eye, five sheep were sacrificed by order of my uncle, and the procession passed between the carcases and the severed heads, the meat being divided between the policemen, musicians, and others.

By this time I had climbed up to the gateway, and from it I caught sight of hundreds of men bearing lamps, and finally saw my beloved pass under where I was standing into the outer court of the house. Here my uncle, welcoming leer, took her hand and led her to the chamber [81] prepared for her. Rue was burnt in front of her, and Shirin threw a gold piece into the brazier. This too is a very ancient custom for averting the evil eye.

Shirin was then kissed by my mother, and I was conducted into the chamber, and a jug and basin were prepared when I removed the Dolagh [7] of Shirin and she removed the socks from my feet. One of the women servants poured out water and I washed the big toe of her right foot and then of her left, Shirin doing the same for me; and, when this was done, we both threw a gold piece into the basin.

After this I tried to remove the veil to see her face, but I only succeeded after making her a present of a pair of golden bracelets studded with turquoises. We gazed intently at each other’s face in the great mirror, and I nearly swooned with joy to feel that, at last, Shirin was in my home.

I next started conversation by inquiring after her health, and before she uttered a word in reply I had to put a few gold coins into her mouth. The tablecloth was then spread, and we both partook of some of the bread, cheese, and salt brought by the bride; and put mouthfuls of rice [82] into each other’s mouths. At this point I presented Shirin with a necklace of Bahrein pearls, an heirloom of my great ancestor; and this gift made my bride speak freely at last, as the other ladies examined it with envy:

The beauty of my beloved is independent of my incomplete love,

Her beautiful face is not in need of rouge, colour, tattooing, or a mole.

At length our lady friends and relations all departed, and as the argent moon soared through the star-spangled sky I murmured:

’Tis a deep charm which makes the lover’s flame,

Not ruby lip, nor verdant down its name:

Beauty is not the eye, look, cheek, and mole,

A thousand subtle points the heart control.

At that moment the bulbul in the rose-bushes broke out into an ecstasy of song, and its notes and the intoxicating smell of the jasmine made an earthly paradise of what was now the home of Shirin.

¶ Footnotes

67:1 If a girl be dangerously ill, her parents frequently vow that, should she recover, they will marry her to a Sayyid; or if, at first they have been disappointed in their hopes of children, a similar vow is made. ↩︎

68:1 The becoming head-gear of Persia is made of the skin of the unborn lamb, and costs about £4 if of good quality. ↩︎

71:1 The Oriental believes that pearls are formed by the crystallization of drops of rain falling on the oyster. ↩︎

71:2 Abru is literally “water of the face,” and thus the wind, the earth, water, and fire are all included.

The first verse is by Danish, Meshedi, who received 100,000 rupees as a reward from the son of Shah Jahan, the Moghul Emperor. Our author would reply to a charge of plagiarism that both he and Danish, by chance, had the same beautiful idea. This is termed Tavarud or coincidence. ↩︎77:1 Majnun wasted away for the love of the famous Laila. ↩︎

77:2 According to lunar mouths the day begins at sunset. Thus Friday night, by European calculation, would be Thursday night. ↩︎

81:1 Dolagh is the garment worn out of doors, combining stockings and trousers. ↩︎