[ p. 25 ]

[ p. 26 ]

¶ BOOK ONE — HOW IT ALL BEGAN

I. Magic

1 : How the savage tried to explain the evils that befell him — he imagined all objects were animate — self-preservation and magic. 2: Religion and faith defined — the technique of magic — the dawn of the idea of the “spirit” — animism. 3: Man begins to think he can exploit the spirits — shamanism — the charlatan in the early advance of religion. 4 : Fetishism. 5 : Idolatry — the beginning of sacrifice — of prayer — of the church. 6 : Taboo.

II. Religion

1 : The attempt to coerce the spirits gives way to the attempt to cajole them — but magic does not disappear — sacrifices. 2: The seasonal festivals — sex rites — the sacraments. 3: How the great gods were created. 4: How the ideas of sin. conscience. and future retribution arose — religion saves morality for a high price — prophet vs. priest. 5 : How religion made society possible — and desirable — how it gave rise to art — the significance of Primitive Religon.

[ p. 27 ]

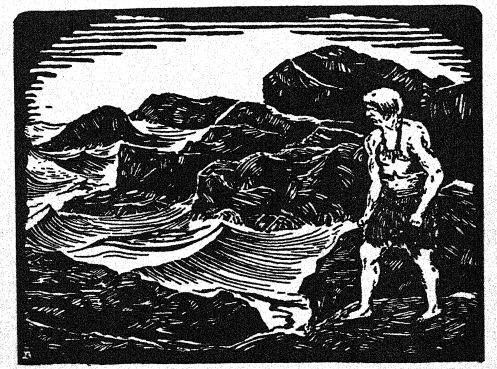

IN the beginning there was fear; and fear was in the heart of man; and fear controlled man. At every turn it whelmed over him, leaving him no moment of ease. With the wild soughing of the wind it swept through him; with the crashing of the thunder and the growling of lurking beasts. All the days of man were gray all his universe seemed charged with Earth and sea and sky were set against him; a relentless enmity, with inexplicable hate, they were t on his destruction. At least, so primitive man concluded. … It was an inevitable conclusion under the circumstances, for all things seemed to be forever going against man. Boulders toppled and broke his bones; diseases ate his flesh; death seemed ever ready to lay him low. And he, poor gibbering half-ape nursing his wound in some draughty cave, could only tremble with fear. He could not give himself stoical courage with the thought that much of the evil that occurred might be accidental. He could not so much as conceive [ p. 28 ] of the accidental. No, so far as his poor dull pate could read the riddle, all things that occurred were full of meaning, were intentional. The boulder that fell and crushed his shoulder had wanted to fall and crush it. Of course! . . . The spear of heaven-fire that had turned his squaw to cinders had consciously tried to do that very thing. Obviously! . . .

To the savage there was nothing absurd in the idea that everything around him bore him malice, for he had not yet discovered that some things were inanimate. In the world he saw about him, all objects were animate: sticks, stones, storms, and all else. He shied at each of them suspiciously, much as a horse shies suspiciously at bits of white paper by the roadside. And not merely were all things animate to the savage, but they were seething with emotions, too. Things could be angry, and they could feel pleased: they could destroy him if they so willed, or they could let him alone.

Perhaps, as Professor George Foot Moore slyly reminds us, even civilized folk instinctively cling to that primitive notion. Children angrily kick the tables against which they bump their heads, as though those tables were human. Grown men mutter oaths at the rugs over which they stumble, for all the world as though those rugs had intentionally tried to trip them. And it may be that young and old still do such irrational things only because even today there still lingers in the mind of man the savage notion that all objects are animate. When caught off his guard, man still is betrayed into trying to punish, either with a blow or with consignment to hell-fire, the inanimate objects that happen to cause him pain.

[ p. 29 ]

After all, civilized people at bottom are perilously close to the savage. Instinctively he too wanted to thrash whatever seemed to bring him evil. Only he was afraid. From experience he knew that fighting was useless, that the enemy-objects, the falling boulders that maimed him, and the flooding streams that wrecked his hut, were in some uncanny way proof against his spears and arrows. That was why he was finally forced to resort to more subtle methods of attack. Since blows could not subdue the hostile rocks or streams, our ancestor tried to subdue them with magic. He thought words might avail: strange syllables uttered in groans, dr meaningless shouts accompanied by beating tom-toms. Or he tried wild dances. Or luck charms. If these spells failed, then he invented others: if those in turn failed, then he invented still others. Of one thing he seemed most stubbornly convinced: that some spell would work. Somehow the hostile things around him could be appeased or controlled, he believed; somehow death could be averted. Why he should have been so certain, no one can tell. It must have been his instinctive adjustment to the conditions of a world that was too much for him. Self-preservation must have forced him to that certainty, for without it self-preservation would have been impossible. Man had to have faith in himself, or die — and he would not die.

So he had faith- — and developed religion.

¶ 2

RELIGION is not all of faith, but only a part of it. By the word faith we mean that indispensable — and therefore imperishable — illusion in the heart of man [ p. 30 ] that, though he may seem a mere worm on the earth, he nevertheless can make himself the lord of the universe. By the word religion, however, we mean one specialized technique by which man seeks to realize that illusion. It was by no means the first such technique to he invented by man; and it may not be the last, either. Long before man thought of religion, he tried to control the “powers” of the universe by magic. When the “dawn man” became sufficiently awake to be conscious of his life and of the innumerable hazards that threatened it, he did not first pause to examine those hazards; no, instead he first set out to avert them. He saw on every side of him the fell and bewildering “powers,” and illogically (but naturally) his first concern was not how they worked but how they could he avoided. If he speculated about them at all, he probably decided the very objects he saw had an animus against him — the actual storms and streams and preying beasts. Only later, much later, did he advance sufficiently to be able to think of those “powers” not as the objects themselves, but as invisible spirits inhabiting them. Primitive man was utterly unable to draw fine distinctions between soul and body, between spirit and matter. He merely knew trees that crushed him, caves that smothered him, mountains that roared and belched lava that destroyed him. That was as far as his puny mind could carry him.

But at last the day did come when, like the stealthy climb of a slow dawn, that idea of the spirit crept into man’s head. It came to him almost unavoidably. Of a morning he awoke, looked up bewilderedly at the familiar rocks of his cave, and gasped, “Hello, that’s [ p. 31 ] queer!” — or sounds to that effect. For there he was, just where he had been when he had stretched out and fallen asleep the night before — and yet he knew he had wandered very far from that place during the interim. He was quite certain of it! Very vividly he remembered fighting huge beasts during the night, or hurtling down ravines, or devouring whole mastodons, or flying. . . . And yet there he was, still lying in his smelly cave, for all the world as though he had never for a moment left it! . . .

Of course, we civilized folk would explain the mystery by simply saying the fellow had had a dream. (Which is perhaps not so much of an explanation at that.) But he, poor savage, could not even remotely guess at such an explanation. The idea of a dream was as foreign to his mind as the idea of a monocle or a wardrobetrunk. No, the only acceptable explanation he could offer himself was the obvious one that he was dual: that he possessed not merely a body but also a spirit, and that while his bodv had that night remained decently [ p. 32 ] at home, his spirit had gone a-roaming. . . . Why not?

There were other experiences which that answer seemed to explain. There was, for instance, death. Here was a body erect and vibrant one moment, and prostrate, inert, the next. What had happened to it? . . . Obviously the same answer fitted : its soul had fled.

Just what was the soul and what the body, the savage could not be certain. He rather thought the soul might be the breath, since that always fled at death. (And that is why the Japanese word for soul used to be “wind-ball,” and the one for death, “breath-departure.” Similarly, that is why the Hindu word for soul it still atman, parent of the German word Ahtem, meaning “breath,” and of the English word “atmosphere.”) But the savage had to imagine the soul might also be something else than the breath, for he saw souls in unbreathing things, too. Indeed, he saw souls in all the things he came across. His whole world thronged with souls.

Historians nowadays call that stage in the development of religion the “animistic,” from the Latin anima, meaning “spirit.” There are millions of savages in the world even today who still remain bogged in that animistic stage of religion. They dwell in India and Africa and other far-away places, clinging there to a primitive faith which once must have been the faith of all human beings.

¶ 3

EVEN at the dawn of the animistic stage there could have been little in the heart of man save fear — and the hate born of fear. Only two kinds of spirits did the savage then seem to know: those that were neutral, and [ p. 33 ] therefore demanding no attention, and those that were hostile, and therefore to be driven away or circumvented. For instance, almost everywhere the ghosts of the dead were considered hostile. Because such ghosts were thought to hang like wraiths over the bodies they had once occupied, corpses were always put away with the most fearful and painstaking thoroughness. And after the burial the survivors usually tried to disguise or hide themselves so as to escape the ghosts. They would paint themselves white (if they were black) or black (if they were white) ; and they would bar the doors of their huts or hide in caves. (That is why we still “go into mourning” when a relative dies, putting on black garments and drawing down the blinds on the windows.) …

Not for a long time, it seems, did man cease to assume that the active “powers” were all unalterably hostile, and therefore to be driven away. Not until many centuries had passed did it occur to him that some spirits might really be friendly, or that even hostile spirits might in some way be won over and made friendly. But once that change did come, a complete revolution in the practice of religion ensued. Instead of spending all his time inventing ways merely of driving the spirits away, man now began to try to bring some of them near. And therewith a new era opened in the history of the race. The first stirrings of confidence began to warm the blood of man, and slowly his cringing back began to straighten. Fear received its first decisive setback, and the promise of civilization drew its first breath. For then at last man dared to think he could actually exploit the spirits! . . .

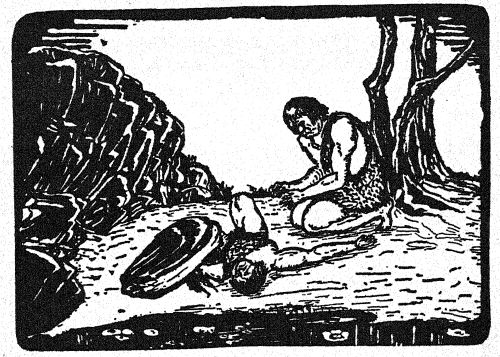

Now there were two main ways in which man tried [ p. 34 ] to exploit the power of a spirit One was to conjure it into some individual, a medicine-man, or as he was called in primitive Siberia, a shaman. Originally the shaman was probably an epileptic, a person given to fits which could be explained only on the ground of “possession.” The shaman was esteemed to be “possessed” by a strange spirit, a formidable and perhaps violent spirit that could do things both foul and fair. So if a man had a fever he went to his tribal shaman, and the latter tried to drive it out by pitting his own “familiar spirit” against the fever-spirit in the patient. If he failed on the first attempt, he tried again, using a more elaborate ritual the second time. Perhaps he made the patient smear himself with excrement, or do something else equally extraordinary. Then he, the shaman, would go off into a fit in which he would dance madly, utter ghastly shrieks, beat fiercely on a tom-tom, or shake a horrid-sounding rattle. Perhaps he would carry on in that manner through a whole night, raving, dancing, and making faces, all to drive the bad spirit out of the patient. And the more elaborate he made the performance, the more wonderful and powerful he appeared in the eyes of the patient. Failure seemed altogether impossible after such efforts — and often was.

But the shaman was not employed solely to drive out the evil spirits. More often, perhaps, he was employed to drive them into people. Because of the spirit that was supposed to be at his beck and call, the shaman was thought to be able to do evil as well as good, to send disease and defeat and death to one’s enemies, as well as bring relief and life to one’s friends. That was why the shaman usually became the tribal leader. The braves [ p. 35 ] stood in constant need of him, for without his “medicine,” without his spells and curses, they believed themselves lost in war as well as in peace. He seemed the one effective instrument with which they could bludgeon the “powers” arrayed against them, the one valid means by which they could master the universe. So they clung to him with all their might and main, fearfully doing homage to him because of the magic power he was supposed to possess.

Of course, the moment the falsity of a particular shaman’s pretensions was definitely established, the poor fellow was never forgiven. The savages turned on him mercilessly and put him to death, perhaps with the most fantastic tortures. They had no use for medicine-men whose medicine didn’t work. . . . For that reason it was only the conscious charlatans among the shamans who succeeded most and survived longest. The rest, the innocent ones who were fools enough really to believe that they could command the spirits, were easily exposed and soon snuffed out. They were not shrewd enough to see the essential falsity of their own claims, and therefore they were totally unable to keep others from seeing it. And, amazing as it may sound, that situation proved to be of vast benefit to mankind. As Sir James G. Frazer remarks in his great work, The Golden Bough, honest fools must have worked far more mischief in primitive society than clever knaves. Only the individual who was sufficiently superior to his fellowmen to be able to think of cheating them, was able at the same time to help them. Without any conscious desire on his part, the good resulting from such an individual’s sagacity almost inevitably outweighed the evil [ p. 36 ] accomplished by his guile. The emergence from the slime of primitive stupidity of a class of cunning shamans was therefore of genuine advantage to civilization. It took the direction of tribal affairs out of the hands of the old (whose only distinction was their age) and the strong (whose only distinction was their brawn) and put it in the hands of the shrewd and far-sighted. Indeed, the rise of shamanism was perhaps the most fundamental factor in the whole development of early government. …

¶ 4

BUT shamanism was only the less common of the two ways by which primitive man tried to exploit the spirits. The other, fetishism, was far more widespread because far more easily handled. The word “fetishism” comes from the Portuguese feitico, meaning a saint’s medallion or relic worn as a good-luck charm. It is now the technical term for the belief that an active spirit dwells in some particular object, and that the mere possession of the object brings with it the power to control its spirit. The first fetishes were probably pebbles with markings which happened to attract the eye of the savage because of their extraordinary color or shape. (Millions of people in the most civilized lands still believe in such “lucky stones.”) Later on, however, fetishes were manufactured. Frequently they were little pouches containing objects with reputedly magic properties. The hair of a lion was put in to give courage, a bit of human brain for cunning, an eyeball for keen vision, a tiger’s claw for ferocity, and so forth. The savage gathered a whole collection of such fetishes on a string, and hung [ p. 37 ] them around his neck, or fastened them over the door of his hut. (Some scholars say our wearing of crosses around the neck, or fastening of horseshoes and mezuzoth to the door, is but a survival of that savage fetishism.) With those amulets on his person, the savage was no longer so afraid. He felt himself better able to fight off the hazards of life and imagined himself more of a match for the universe. When in need, he simply called on one of his fetishes for help; and if the help was not soon forthcoming, he angrily upbraided the thing for its laziness. If it still remained obdurate, he simply flung it away and got himself another.

It took only a little while, of course, for the manufacture of fetishes to become a sacred profession. For [ p. 38 ] one reason and another, certain individuals came to be looked on as the makers of the most potent fetishes. They made them not alone for the individual members, but also for the tribe as a whole. And thus it came to pass that even in lands where shamanism was unknown the professional holy man, the priest, made his advent. He was inescapable. . » .

¶ 5

TRIBAL fetishes, like private ones, were originally natural objects: for instance, boulders of a peculiar color, or trees of a strange shape. The Kaaba Stone, still worshipped by Moslems in Mecca, was originally just such a tribal fetish.) Later, however, even these tribal fetishes were also manufactured. The boulder or treetrunk was carved in some significant manner by the fetish maker, and became — an idol. It is impossible to say just where fetishism ends and where idolatry begins. The one grows into the other as the child grows into the youth.

Probably the idol was used in the beginning solely as a sort of scarecrow to drive the evil spirits away. Later, however, it was so carved that it had a less fearsome appearance, and was used for other purposes. Even more than to scare the evil spirits away, it was used now to bring the good spirits near. The idol was. smeared with blood or oil, in the hope that some good spirit might come and lick the redolent bait — and perhaps remain. And then periodically the smearings were renewed in order tp hold the good spirit fast. Again and again they were renewed, until in time the practice became a fixed rite. After that, in the place of mere smearings of blood, [ p. 39 ] whole carcasses were offered to the good spirit lodging in the idol. And thus sacrifice began. . . .

Food was brought, the rarest and richest obtainable, and the priest ceremoniously offered it to the spirit resident in the idol. As to a dread chieftain, it was offered with many bowings and scrapings and ceremonial songs. And with many words of praise, too, for the spirit was thought to be vain as well as hungry. And thus prayer was born. . . .

In time a shelter was considered necessary for the idol: a cleft in a rock or a shady tree at first, and later a rude hut. And thus the first church was built. …

It was all a most natural process of development. Once man took it into his head that in order to live he must master his universe, then animism, fetishism, idolatry, priestcraft, sacrifice, prayer, and the church — all [ p. 40 ] these were nigh inevitable. Primitive man, drowning in fear, clutched desperately at the spirits, as a man drowning in a stream might clutch at the reeds by the bank. Of course, one after the other the spirits failed him — even as the reeds break in a drowning man’s hands. But still the savage continued to clutch at the spirits. It was almost instinctive with him. He could not help it. . . .

¶ 6

BUT the savage by no means imagined it was safe to clutch at every reed by the side of his tarn of fear. On the contrary, most of them he considered highly dangerous, and he tried with almost panicky care to avoid them. Those harmful spirits were what the savage in the Malay Archipelago still calls taboo, “marked.” A sort of fiendish electricity was supposed to he in them, so that if one touched them they maimed or even killed.

All sorts of objects and actions were considered taboo: some because they were so holy, and others because they were so demoniac. Usually the name of the god was taboo, and therefore it dared not be uttered save at certain holy moments by officially holy men. (That primitive superstition still has its finger on the lips of man, holding him from speaking God’s name in ordinary conversation.) The flesh of certain holy or of certain particularly unholy animals was considered taboo, and therefore might not be eaten. (That primitive superstition is responsible for the aversion to pork which marked the ancient Egyptians, arid still marks the Jews and Moslems.) Marriage with a close relative, touching a corpse, killing one’s fellow-tribesman, wearing clothes of mixed wool and cotton, stealing a fellow- tribesman’s [ p. 41 ] wife, kindling a fire on a holy day, cursing one’? own father, uncovering the head before an idol — all these acts and myriads of others, some of them socially criminal, most of them socially meaningless — were in one religion or another considered taboo. Or their very opposites were occasionally considered taboo.

Certain taboos were temporary, as for instance the one branding a woman as contaminated for the length of the menstrual period. Others were permanent, as for instance the one outlawing a man guilty of accidentally killing a fellow-tribesman. In some cases, the tribes themselves were required to attend to the punishment of the transgressor; in others, punishment was supposed to be dealt in some magic way by the violated spirits directly. The transgression of certain taboos entailed [ p. 42 ] disaster to every member of the tribe to which the transgressor belonged; in other instances punishment was confined to the transgressor alone. In some cases punishment could be evaded by elaborate penance and cleansing on the part of the transgressor; in other cases immediate death was inescapable. The variants were innumerable. . . .

Even today most people are inhibited by taboos. Superstitiously they dread to do all sorts of meaningless little things. They refuse to sit thirteen at a table, or walk under a ladder, or light three cigarettes with one match. They are thrown into a panic if a mirror breaks in their house, or a black cat crosses their path; and they dread to tell of their own good health without “knocking on wood” or mumbling “Unbeschrieen.” Ever, people otherwise quite intelligent will sometimes be terrified by one or another of these stupid taboos. No wonder, therefore, if the savage suffered himself to become altogether taboo-ridden. Poor child that he was, his whole life settled down into an incessant and frantic struggle to keep away from all that was “marked.”