[ p. 134 ]

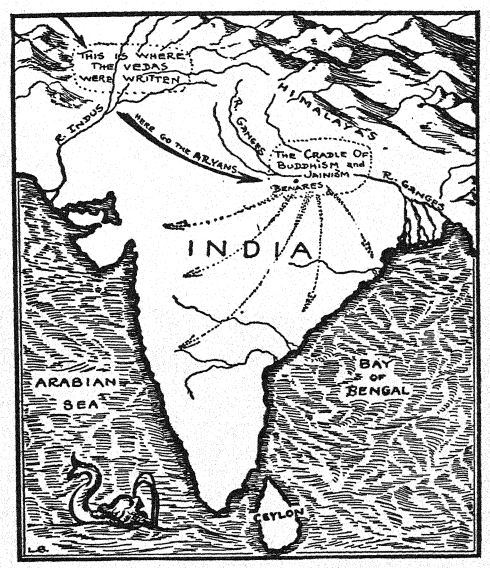

BUT Jainism was only the less important of the two great heretical religions that arose in India in the sixth century B. C. When Mahavira was already almost forty years of age, there was born in India a male child destined to found the far greater religion of Buddhism. The name of this child was Siddharta Gautama, and his father was a wealthy rajah in the valley of the Ganges. Gautama in his birth was therefore strikingly like the man who founded the earlier heresy; and, as we shall see, in his life he was even more like him. At an early age Gautama too was married off to a beautiful princess; and until he was almost thirty he, too, reveled unrestrained in princely luxury.

But then of a sudden something came over him. Exactly as had happened to Mahavira, a revulsion against pleasure took hold of this young prince so that he no longer could abide the lusts of the flesh. His eyes were suddenly opened to the unutterable misery of all life, and the sight so burnt its way into his soul that he nevermore could be at ease in his palace. One night he arose and, tiptoeing into the room where lay his sleeping wife with their new-born child in her arms, he took one last fond look at them both, and fled. Off into the night he sped, with his trusted charioteer by his side. Very far he rode, not halting until the rising of the sun had shown that he had already got far beyond the lands of his clan. Then he dismounted, cut off his flowing locks, tore the jewels and ornaments from his clothes, and giving them together with his horse and sword to the charioteer, commanded that they be [ p. 135 ] returned to his wife. Gautama himself did not go back, but turning his face toward the hills, he went off alone on foot. But even then he did not feel free. Not until he had exchanged clothes with a beggar he met on the road did he feel himself loosed at last from all attachments [ p. 136 ] to the world of vanity. Not until he stood there on that dusty road a ragged vagrant without a possession on earth did he feel himself able at last to go forth undistracted in search of salvation.

Southward Gautama took his way into a range of hills where dwelt certain hermits in caves. He had long known of these hermits, for their fame had spread throughout the countryside. They were not ordinary ascetics frantically starving their bodies, but rather devoted philosophers trying to enrich their minds. Most of their time was spent in the pursuit of knowledge — not knowledge about the facts of life, however, but about the destinies of the soul. They did not poke about in laboratories as do our modern investigators; rather they sat under trees and talked. Long and earnestly they conversed about those metaphysical things our material world does not know. Their great concern was how to lose themselves in the Brahma, in the universal OverSoul which was the only reality they knew. They were sick of this futile, finite, tortured existence called life. They wanted to cut away from it, cut clear away from the individual self and attain a sense of finality and security through absorption into the universal All. They craved release from the vicious round of transmigrating life; they craved everlasting extinction. Eyelids are heavy in the sweltering tropics, where the wet jungle heat breeds life too rankly; and these unhappy hermits wanted to sleep — to sleep forever. And because Gautama, too, wanted to sleep forever, he joined himself to their company. And Gautama came and took part in their conversation.

But the wandering prince did not tarry with them [ p. 137 ] long. His mind was keen, and it took little time for him to discover how empty was the ratiocination of those talky hermits. They tried to drag their petty souls to Brahma by strings of words — but Brahma Itself, he discovered, was also a mere thing of words. He saw through all the arguments, no matter how smoothly and plausibly they were put, and he realized that Brahma, the great “It,” was essentially no more real than man, the little “it.” So, taking five of the hermits with him, he went off into the jungles to try another road to salvation. With all his being he now gave himself up to years of self-mortification, striving, as had Mahavira before him, to reach Nirvana through pain. For six years — at least, so we are told — he practiced austerities the like of which had never before been seen in the land, living on a grain of rice a day, or on a single sesamum seed. But, unlike Mahavira, no success attended his efforts. Despite all Gautama’s austerities, those six years were “like time spent striving to tie the air into knots.” So finally he gave up the vain struggle. He had to confess to himself at last that senseless and irrational self-affliction was not enough. In despair he had to admit that the dismal path of mere denial could never be for him the way to peace.

And so once more Gautama set off alone, far unhappier now than ever before. He had tried the ordinary life of the prince, and it had left a taste as of ashes in his mouth. He had tried the life of the philosopher, and that too had brought him no peace. And then he had tried the life of the ascetic, only to find that even in that there could be no release. So now he was lost, utterly at sea on a night that seemed to hold no faintest gleam of light, no slightest promise of dawn.

[ p. 138 ]

And then of a sudden light broke on him. . He was seated one day beneath a banyan tree, his spirit at its lowest ebb, when all without warning salvation came to him. In an instant his spirit leaped up in ecstasy; his whole being became suffused with joy. He felt himself released at last, released from life and the fear of life. He felt himself free at last, free and safe and secure.

[ p. 139 ]

¶ 2

IN essence what Gautama had learnt was the folly of all excess. It had come to him in that moment of illumination that it was just as stupid to go mad with pain as it was to get drunk with pleasure. He had suddenly come to see that asceticism inevitably overshot its mark, that it missed the very thing it was after because it went after it too wildly. He had discovered that the frantic excess with which the ascetics strove to curb desire meant only that they were letting desire run away with them. … So Gautama came forward with a new gospel which he called the Four Truths. They were these: First, both birth and death bring grief, and life is utterly vain. “The waters of the four great oceans,” he declared, “are naught compared with the tears of men as they tread the path of life.” Secondly, the vanity of life is caused altogether by the indulgence of desire. Therefore, thirdly, the vanity can end only with the ending of all desire. But fourthly — and herein lay the whole originality of the gospel — all desire can be ended not by excessive asceticism but by sane and intelligent decency! The road to salvation, according to Gautama, was therefore not the tortuous trail of bodily self-destruction, but rather the “Middle Path” of spiritual self-control. It was the Eightfold Noble Path of “Right Belief, Right Resolve, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Thought, and Right Meditation.” Nirvana was, after all, not a physical condition but a state of mind, and therefore it could be reached not through physical torment but mental discipline. The blessedness of [ p. 140 ] freedom, of everlasting passionless peace, of Nirvana, could be attained only by destroying the three cardinal sins: sensuality, ill will, and stupidity.

Now the implications of such a gospel were grave and revolutionary beyond words. In the first place, they left no room whatsoever for gods, priests, or prayers. “Who is there that has ever seen Brahma face to face?” cried Gautama scornfully. Or with regard to prayer: “Could the farther bank of the river Akirvati come over to this side no matter how much a man prayed it to do so?” Thus it scouted the whole sacrificial system of the brahmins. It condemned outright that shameless ritualization of morality which the priests had introduced with their Brahmanas. Indeed, it condemned not alone ritual but religion itself that is, in its narrower connotation. Gautama’s gospel countenanced none of those common instruments— gods, sacrifices, priests, or prayers — wherewith the religious technique is always practiced. . . . But in the broader connotation of the term, the gospel was itself a religion. It tried desperately to find a way of escape from the insecurities of life, and to that extent it was most generously a religion. It tried earnestly to rid man of fear, to make him feel at home in the universe— and for that reason it deserves its chapter in the story of this believing world. …

But opposition to the gods was not die only radical implication of Gautama’s gospel. A second and perhaps just as radical implication was its opposition to all caste divisions. According to Gautama there were no valid distinctions between high-bom and low-born, for men could be judged only according to their deeds. Very [ p. 141 ] explicitly he declared: “A man does not become a brahmin by his family or by birth. In whom there is truth and righteousness — he is blessed, he is a brahmin. O fool, if within thee there is ravening, how can’st thou make the outside pure?” Gautama, who had belonged to the princely caste, realized all too well how empty were all distinctions of birth. Though born and reared in a palace, life for him had been no whit Iks futile and troubled than the life of the lowest serf in his wattle-and-daub hut. So how could he respect the trumpery social distinctions of the brahmins?

But the revolt against the gods and the revolt against the castes were neither of them unique to Gautama’s gospel. Mahavira had urged them just as emphatically when Gautama was still a child in arms. What alone was original in the younger heresy was the emphasis Gautama laid on social ethics. Mahavira had insisted that each man could attain salvation for himself by going off alone and afflicting his own body. But the younger prophet declared that all individualism was sinful, and that one’s own salvation could be found only in the effort to bring salvation to every one else. “Go ye now,” he commanded his followers, “out of compassion for the world and the welfare of gods and men . . . and preach the doctrine which is glorious.” And thus he cut at the very root of selfishness. One’s own peace, he declared, could be found only in seeking peace for all humanity. . .

Now Gautama arrived at that conclusion from a rather startling and original premise. Unlike all other Hindu thinkers of his day, he did not believe in the individual soul. Just as some modern psychologists [ p. 142 ] claim the soul to be no more than the name for a certain class of subtle muscular reactions, so Gautama claimed it to be no more than a name for the totality of human desires. As he himself put it: the chariot is made up of wheels, shaft, axle, carriage and banner-staff, and has no real existence when these are removed; and just so the soul is made up of desires and psychic tendencies, and disappears the moment these are taken away. Therefore, argued Gautama, all this pother about the transmigration of souls was sheer folly. Only the deeds, not the doers, lived on from generation to generation. So no matter how anxiously a man looked after what he called his soul, no whit of good could possibly result from it. Only if a man diligently watched his deeds could he possibly attain salvation. For there was an inexorable Law of Karma, an inescapable “law of the deed,” in the universe. The effects of all actions lived on perpetually, good breeding good, and evil breeding evil. And these effects could never be eluded. “Not in the sky, nor in the midst of the sea, not in the clefts of the mountains, is there known a spot where a man can be freed from an evil act.” So every man’s fate depended not on what he was but what he did Only if he did that which was righteous m the eyes of men, only then could he throw off the ball and chain of evil consequence and attain the blessed release of Nirvana. . .

¶ 3

SUCH in brief was Gautama s gospel after the revelation came to him beneath the banyan tree. He sought to communicate it first to the five disciples whom he had [ p. 143 ] left behind when he forsook asceticism. But these men looked on him as an apostate, and would not even receive him on his return. Only after much persistence could Gautama get them to give ear to his doctrine, and then he had to argue with them five days long. But in the end he won them over. With one accord those five men then hailed him as the Buddha, the “Enlightened One,” for they had become convinced that he could not but be another of those chosen souls, the Buddhas (in Jainism they were called the Jinas), who from time to time were supposed to descend into the world to speak celestial truth. And then a little holy brotherhood was created around the person of this new Buddha.

India was then swarming with restless souls in search of a faith that might comfort them; many of these came and found it in the words of Gautama. They gathered in the Deer Forest near Benares, and built themselves little huts around the dwelling-place of the Buddha. And when they were as many as sixty in number, their master commanded them to go forth during the dry months of the year and carry his comforting message to the people. He told them to carry abroad the good tidings that salvation was free, and that all men, high and low, learned and ignorant, could surely attain it if only they practiced justice and righteousness.

Buddha himself went out into the country with that evangel. For twenty years he wandered far and wide, winning disciples wherever he moved. Early in his ministry he went back to his own home, and there converted his long-deserted wife and son to the new faith. (His son even became one of his preaching [ p. 144 ] monks, and bis wife joined an order of Buddhist nuns which was soon organized.) And thus, the center Tn ever-growing movement, Siddharta Gautama the Buddha, lived out his days on earth. To the end he continu d to instruct the disciples that gathered during every rainy season in the Deer Forest near Benares^ Indeed, the very last words he uttere were re J®e to them. “Work out your own salvation!” he told them with his last breath. And then he died. . . .

More than twenty-four hundred years have passed since Siddharta Gautama passed away, and it is not easy for us to appreciate how revolutionary his doctrine must have been when first he uttered it. Never before had it been said in India that salvation was obtainable in any wise save through scrupulous sacrificing, or profound philosophizing, or extravagant asceticism. In other words, never before had it been asserted that those who were too poor to offer sacrifices, too dull-witted to indulge in philosophy, or too human to set upasjmchorites could possibly be saved. Only when Gautama te Bukdha took the field was that assertion made. Until then salvation, and even the hunger for salvation, had been deemed privileges open only to the few. But with the coming of Gautama they were held out to the many—to all. According to him even the lowiest in the land could attain Nirvana, if only they followed the Noble Eightfold Path. . . . And though that gospel was afterward distorted and corrupted and changed out of all likeness to what it had been when it came fresh from the lips of to Buddha, nevertheless it did endure and spread until its light was known over all the East.

[ p. 145 ]

¶ 4

BUT his gospel did not spread at once. For years Buddhism remained an obscure and unimportant sect, probably just one of many heretical movements fermenting away in the troubled India of those centuries. For a while it was no more than a mere ascetic order similar to Jainism. The very selfishness which Gautama had most bitterly attacked, took hold of his professed followers, and they became far more concerned about the peace of their own little souls than the peace of all mankind. But about the third century B. C. there came a revival of Buddha’s world-saving spirit, and monks once more went out to preach a gospel in his name.

Only now it was no longer the simple ethical gospel of Gautama. Theology had crept in, and it became a religion in the very narrowest sense of that word. Time had dealt hard with the memory of Gautama, and by the third century he was no longer imagined to have been a man but a god. A new school of Buddhist thought called the Mahayana, the “Greater Vehicle,” arose, and according to its teaching Buddha had been from the beginning a divine being. The earlier school, the Hinayana or “Lesser Vehicle,” had been content to picture Gautama as altogether a human creature. It had frankly told in its writings how the master had occasionally suffered from wind on the stomach, and how once when he ate a meal prepared by a blacksmith he was attacked by dysentery and almost died. But the new school was totally incapable of such realism. It told instead how the Blessed One had been conceived supernaturally and had been born without pain. It [ p. 146 ] described him as a sinless being who had been sent from heaven as the savior of gods and men. It further declared that his divine spirit continued regularly to return to the earth, incarnating itself generation after generation in certain exceptionally holy men called Bodhisattvas, “Living Buddhas.” And thus it opened a way for the incursion of a whole troop of extra gods. And finally it allowed idols of Buddha to be set up in splendid temples, and even encouraged the offering of sacrifices of flowers to those idols. Just the very elements in the old Brahmanic religion against which Buddha had most directly rebelled came sidling over to the protestant faith, and through the Mahayana took possession of it.

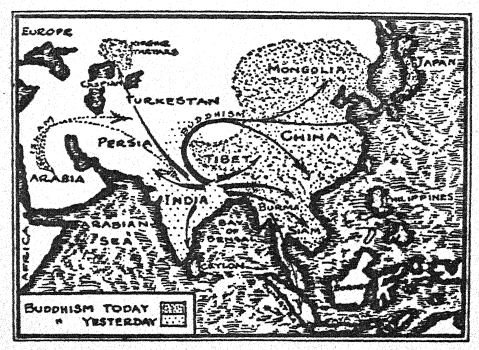

And now, bedizened with idols and made colorful with myths, Buddhism began to spread at last. Power and riches began to flow to the sect, and before long the tiny huts in which the preachers had been wont to shelter themselves during the rainy season were replaced by imposing and costly monasteries. The rajahs of India were just then struggling to wrest supremacy for themselves from the hands of the long-dominant priestly caste; and these rajahs began to see the value to their cause of this virile caste-destroying movement. Especially did one of them, a certain low- caste adventurer named Chandraguptra, see its usefulness. By war and intrigue he had managed to carve out for himself a vast empire in northern India, and because the anti-caste doctrine of Buddhism promised to help him retain bis power, he endowed its monasteries with vast estates and enormous riches. And his grandson, the famous King Asoka who became emperor of India in 264 B. C., [ p. 147 ] devoted a great share of his energy during all his reign to the spreading of the Buddhist religion.

Asoka is esteemed by many scholars to have been the noblest monarch in history; and if the criterion is the number of souls that still revere his memory, then certainly he was a far greater figure than any other in the whole world’s catalogue of kings. By acquiring one state after another he built up an empire that included a large part of the East; and every inch of it he won by faith and not by the sword. Asoka sent out Buddhist missionaries to Ceylon, to Kashmir, and to the uttermost ends of the earth known to him. Eight and twenty years he carried on his far-flung missionary work, and before he died he had managed to make Buddhism the dominant religion in his half of the world.

But of course it was not the simple ethical gospel of Gautama that was carried to these strange lands. Rather it was an intricate theological dogma that translated Buddha into a God. Gautama had preached a religion of morality; but these successful missionaries rather preached a religion that made a morality of ritual. Mere obeisance to the god Buddha was deemed enough to save one’s soul. Nirvana, which to Gautama had been entirely a state of spiritual peace attained by following the Noble Eightfold Path, was now interpreted to be a physical post-mortem heaven won by much kissing of an ikon’s toe. And these corruptions were marked not merely in the Mahayana school of Buddhism which spread to China and Japan, but later also in the Hinayana school which throve especially in Ceylon. The farther Buddhism traveled, the more it changed. On the northwestern frontier of India, where [ p. 148 ] the Hellenic and Hindu worlds touched, the Buddhist idols came to look exactly like the idols of the West. Hariti, a pestilence-goddess whom Buddha was supposed to have converted, was carved to look very much like Isis, the mother-goddess of Egypt. She was even pictured as holding the infant Buddha to her breast, exactly as Isis held the infant Horus and — much later — Mary held the Christ Child.

In China Buddhism took on much of the character of Taoism, and in Japan it was greatly influenced by the national religion called Shinto. Then contact with Christianity began to have its effect, first through the efforts of the early Nestorian preachers, and much later through the activities of Protestant missionaries. Buddhism in Thibet very early took on a distinct Christian coloring, accepting into its ritual such Christian symbols and instruments as the cross, the miter, the dalmatica, censer, chaplet, and holy-water font. The Buddhist religion in Thibet has developed a most elaborate hierarchical system, with a pope, the Dalai Lama, ruling the whole land from his palace at Lhassa, assisted by bishops and priests officiating in vast cathedrals cluttered with images and pictures, and by myriads of monks busily spinning prayer-wheels in high-walled monasteries. And also in Japan Buddhism has more recently taken on Christian coloring, though here of a Protestant shade. Modern Japanese Buddhists are reported to have congregational worship and hymn-singing, Sunday Schools for their children, a Young Men’s Buddhist Association for their men, and Buddhist temperance societies for their women! . . .

In India itself. Buddhism simply withered and died [ p. 149 ] out. A thousand years after the death of Gautama, it had become very largely Brahmanized. The plain people fearfully cried to the idols for help, and the leaders earnestly wrangled about the proper size and cut of their ceremonial robes. When therefore a new religion, Islam, invaded the land, it swept all before it. Although there are perhaps a hundred and fifty million Buddhists in Asia, no more than two thousand of them now remain in all of India.

Buddhism is still the religion of Burmah, Siam, and Ceylon, but in those lands it has fallen back almost to sheer animism. Everywhere in Ceylon one can hear the bellman at sundown calling the naked brown folk with glossy black hair to the service in the temple. They [ p. 150 ] bring candles — if they can afford them — and flowers to the yellow-clad priest; and the latter solemnly offers them to some fetish, perhaps a putative tooth of Buddha, nestling in an innermost shrine. Then there is much praying — praying to gods, devils, angels, demons, saints, and all manner of other spirits. . . . And all the while there stands within that land a mighty tree whose seed came from the very banyan under which Gautama received the revelation. There in Ceylon it still stands, the oldest tree known to history. During nearly twenty -two hundred years it has been tenderly watched and watered; its branches have been stoutly braced, and its soil has been terraced to give room for the gigantic roots to grow. And there it thrives still today, a pitilessly ironic monument to the pitiful stupidity of man. For that tree, a mere thing in nature, has been most carefully preserved and nurtured, while the faith which alone gave it meaning, long, long ago was allowed to perish. …