[317]

¶ SECT. CLVI.—EMPEROR YŪ-RIYAKU (PART VII.—THE HORSE-FLY AND THE DRAGON-FLY).

When forthwith he made a progress to the Moor of Akidzu, [^2324] and augustly hunted, the Heavenly Sovereign sat on an august throne. Then a horse-fly bit his august arm, and forthwith a dragon-fly came and ate up [^2325] the horse-fly, and flew [away]. Thereupon he composed an august Song. That Song said:

“Who is it tells in the great presence that game is lying on the peak of Womuro at Mi-yeshinu? Our Great Lord, who tranquilly carries on the government, being p. 397 seated on the throne to await the game, a horse-fly alights on and stings the fleshy part of his arm fully clad in a sleeve of white stuff, and a dragon-fly quickly eats up that horse-fly. That it might properly bear its name, the land of Yamato was called the Island of the Dragon-Fly.” [^2326]

So from that time that moor was called by the name [318] of Akidzu-nu. [^2327]

[ p. 398 ]

¶ SECT. CLVII.—EMPEROR YŪ-RIYAKU (PART VII.—ADVENTURE WITH A WILD BOAR).

Again once the Heavenly Sovereign made a progress up to the summit of Mount Kadzuraki. [^2328] Then a large [wild] boar ran out. When the Heavenly Sovereign forthwith shot the boar with a whizzing barb, [1] the boar, furious, came towards him roaring. [2] So the Heavenly Sovereign, alarmed at the roaring, climbed up to the top of an alder. Then he sang, saying:

“The branch of the alder-tree on the opportune mound which I climbed in my flight on account of the terribleness of the roaring of the boar, of the wounded boar, which our great lord who tranquilly carries on the government had been pleased to shoot!” [3]

[ p. 399 ] [319]

¶ SECT. CLVIII.—EMPEROR YŪ-RIYAKU (PART IX.—REVELATION OF THE GREAT DEITY OF KADZURAKI, LORD OF ONE WORD).

Again once, when the Heavenly Sovereign made a progress up Mount Kadzuraki, the various officials [4] were all clothed in green-stained garments with red cords that had been granted to them. At that time there were people ascending the mountain on the opposite mountain acclivity quite similar to the order of the Heavenly Monarch’s retinue. Again the style of the habiliments and likewise the people were similar and not distinguishable. [5] Then the Heavenly Sovereign gazed, and sent to ask, saying: “There being no other King in Yamato excepting myself, what person goeth thus?” The style of the reply again was like unto the commands of a Heavenly Sovereign. Hereupon the Heavenly Sovereign, being very angry, fixed his arrow [in his bow], and the various officials all fixed their arrows [in their bows]. Then those people also all fixed their arrows [in their bows]. So the Heavenly Sovereign again sent to ask, saying: “Then tell thy name. Then let each of us tell his name, and [then] let fly his arrow.” Thereupon [the other] replied, saying: “As I was the first to be asked, I will be the first to tell my name. I am the Deity who dispels with a word the evil and with a word the good,—the Great Deity of Kadzuraki, Lord of One [ p. 400 ] [320] Word.” [6] The Heavenly Sovereign hereupon trembled, and said: “I reverence [thee], my Great Deity. I understood not that thy great person would be revealed;” [7]—and having thus spoken, he, beginning by his great august sword and likewise bow and arrows, took off the garments which the hundred officials had on, and worshipfully presented them [to the Great Deity]. [8] Then the Great Deity, Lord of One Word, clapping his hands, [9] accepted the offering. So when the Heavenly Sovereign made his progress back, the Great Deity came down the mountain, [10] and respectfully escorted him to the entrance [11] of the Hatsuse mountain. So it was at that time the Great Deity Lord of One Word was revealed.

[ p. 401 ]

\SECT CLIX.—EMPEROR [YŪ-RIYAKU (PART X.—THE MOUND OF THE METAL SPADE).]

Again when the Heavenly Sovereign made a progress to Kasuga to wed Princess Wodo, [12] daughter of the Grandee Satsuki of Wani, [13] a maiden met him by the way, and forthwith seeing the Imperial progress, ran and hid on the side of a mound. So he composed an august Song. That august Song said:

“Oh! the mound where the maiden is hiding! Oh for five hundred metal spades! then might [we] dig her out!” [14]

So that mound was called by the name of the Mound [321] of the Metal Spade. [15]

¶ SECT. CLX.—EMPEROR YŪ-RIYAKU (PART XI.—THE LEAF IN THE CUP).

Again when the Heavenly Sovereign made a copious feast under a hundred-branching tsuki-tree [16] at Hatsuse, a female attendant from Mihe [17] in the land of Ise lifted [ p. 402 ] up the great august cup, and presented it to him. Then from the hundred-branching tsuki-tree there fell a leaf and floated in the great august cup. The female attendant, not knowing that the fallen leaf was floating in the cup, did not desist from presenting [18] the great august liquor to the Heavenly Sovereign, who, perceiving the leaf floating in the cup, knocked the female attendant down, put his sword to her neck, and was about to cut off her head, when the female attendant spoke to the Heavenly Sovereign, saying: “Slay me not! There is something that I must say to thee:” and forthwith she sang, saying:

“The palace of Hishiro at Makimuku is a palace where shines the morning sun, a palace where glistens the evening sun, a palace plentifully rooted as the root of the bamboo, a palace with spreading roots like the roots of the trees, a palace pestled with oh! eight hundred [loads of] earth, As for the branches of the hundred-fold flourishing tsuki-tree growing by the house of new licking at the august gate [made of] [322] chamæcyparis [wood], the uppermost branch has the sky above it, the middle branch has the east above it, the lowest branch has the country above it. A leaf from the tip of the uppermost branch falls against the middle branch; a leaf from the tip of the middle branch falls against the lowest branch; a leaf from the tip of the lowest branch, falling into the oil floating in the fresh jewelled goblet which the maid p. 403 of Mihe is lifting up, all [goes] curdle-curdle. Ah! this is very awful, August Child of the High-Shining Sun! The tradition of the thing, too this!” [19]

So on her presenting this Song, her crime was [323] pardoned. Then the Empress sang. Her Song said:

“Present the luxuriant august liquor to the august child of the high-shining sun, who is broad like the leaves, who is brilliant like the blossoms of the broad-foliaged five hundred[-fold branching] true camellia-tree that stands growing by the house of new licking in this high metropolis of Yamato, on this high-timbered mound of the metropolis The tradition of this thing, too this!” [20]

Forthwith the Heavenly Sovereign sang, saying: [324]

“The people of the great palace, having put on scarfs like the quail-birds having put their tails together like wagtails’ and congregated together like the yard-sparrows, may perhaps to-day be truly steeped in liquor,—the people of the palace of the high-shining sun. The tradition of the thing, too, this.” [21]

These three Songs are Songs of Heavenly Words. [22] [325] So at this copious feast this female attendant from Mihe was praised and plentifully endowed.

[ p. 404 ]

[ p. 405 ]

[ p. 406 ]

Kefu mo ka mo

Saka-mi-dzuku-rashi.

rendered “may perhaps to day be truly steeped in liquor,” Moribe would like to consider the lines

Asu ma koma

Saka-mi-dzuku-rashi,

i.e., “may perhaps to-morrow be truly steeped in liquor” to have been accidentally omitted. There is no doubt but that their insertion would add to the effect of the poem from the point of view of style.

¶ Footnotes

396:1 p. 397 Akidzu-nu. See Note 4 to this section. ↩︎

396:2b Or, “bit.” ↩︎

397:3 The signification of the greater portion of this Song is clear enough, and is sufficiently explained by the context. The word “who” however admits of two interpretations, Motowori taking it to signify some one,“ whereas Moribe, keeping the literal meaning of ”who?“ sees in it an angry exclamation of the monarch’s at having been brought out to the hunt under exaggerated promises of game. Womuro means ”little cave,“ but is here a proper name. Mi-yeshinu is a form of the word Yoshino which is frequently met with in poetry, the syllable mi being probably, as Mabuchi tells us in his ”Commentary on the Collection of a Myriad Leaves,“ equivalent to ma, and therefore simply an '”Ornamental Prefix.“ The phrase ”tranquilly carries on the government“ represents the Japanese yasumishishi, the Pillow-Word for wa go oho-kimi, ”our Great Lord,“ which latter phrase descriptive of the Sovereign is here put into the Sovereign’s own mouth. ”Of white stuff, shiro-tahe no, is another Pillow-Word. The only real difficulty in this Song meets us is the interpretation of its concluding sentence. The meaning apparently intended to be conveyed is that it was in order to prove itself worthy of its name that the dragon-fly performed the loyal deed which forms the subject of the tale. But it so, the author forgets that it was not the dragon-fly that was called after Japan, but Japan that was called after the dragon-fly (Akidzushima, “Dragon-fly-Island,” from akidzu, “dragon-fly”). What should be the point of the whole poem therefore fails of application. The name “Island of the Dragon-Fly” has already appeared in Sect. V (Note 26). ↩︎

397:4 I.e., Dragon-Fly Moor. See Motowori’s remarks in his “Examination of the Synonyms for Japan,” p. 26. ↩︎

398:1 p. 398 See Sect. LV, Note 1. ↩︎

398:2 See Sect. XXIII, Note, 7. ↩︎

398:3 This is the sense attributed by the commentators to the obscure word utaki, which seems to be only found written phonetically. ↩︎

398:4 Our author cannot be right in attributing this Song to the Emperor, and we need not hesitate to accept the different version of the story given in the parallel passage of the “Chronicle,” where the Monarch, as might be expected from all the other details that have been preserved concerning him, bravely faces the boar, while it is one of his attendants who runs away and climbs a tree to be out of danger, and afterwards composes these lines. This Song is a good instance of what Mr. Aston (in his “Grammar of the Japanese Written Language,” 2nd Edit., p. 194) has said concerning some of the short poems of a later date: “These sentences are not statements of fact; they merely picture to the mind a state of things without making any assertion respecting it.” Here we, as it were, simply see the frightened courtier sitting breathless and terrified amid the branches of the alder, and the whole verse has but the meaning of an exclamation. The term ari-wo rendered “opportune mound.” is the only word in the text which raises any difficulties p. 399 of interpretation. Moribe’s exegesis has here been followed. According to the older view it signifies “barren mound.” For the words “our great lord who tranquilly carries on the government” see Sect CLVI, Note 3. ↩︎

399:1 p. 400 Literally, “the hundred officials.” This Chinese phrase has been met with before in the “Records,” and recurs in this Section. ↩︎

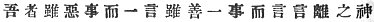

399:2 The original has the character

, out of which it is hard to make sense. Motowori’s proposal to consider it put by error for

, out of which it is hard to make sense. Motowori’s proposal to consider it put by error for  , has therefore been adopted, though the translator feels by no means sure that it is a happy one. According to the strict Chinese sense of

, has therefore been adopted, though the translator feels by no means sure that it is a happy one. According to the strict Chinese sense of  , it would not fit with this passage any better than

, it would not fit with this passage any better than  ; but in Japanese we may be justified in understanding

; but in Japanese we may be justified in understanding  to mean “not distinguishable.” ↩︎

to mean “not distinguishable.” ↩︎400:3 In the original:

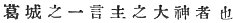

. The import of the obscure expression “dispelling with a word the good” is not rendered much more intelligible by Motowori’s attempt to explain it. For Kadzuraki see LV, Note. 1. ↩︎

. The import of the obscure expression “dispelling with a word the good” is not rendered much more intelligible by Motowori’s attempt to explain it. For Kadzuraki see LV, Note. 1. ↩︎400:4 Literally, “that there would be a present (or manifest) great person.” ↩︎

400:5 I.e., he kept nothing for himself, but from his own sword and bow and arrows down to the ceremonial garments in which his followers were clad, gave every thing to the god. ↩︎

400:6 In token of joy, says Motowori. ↩︎

400:7 The characters

, rendered by “came down the mountain,” are evidently the result of a copyist’s carelessness. The translation follows Motowori’s proposal to emend the text to

, rendered by “came down the mountain,” are evidently the result of a copyist’s carelessness. The translation follows Motowori’s proposal to emend the text to  . ↩︎

. ↩︎400:8 Literally “mouth.” ↩︎

401:1a Wodo-hime. The signification of this name is obscure. ↩︎

401:2a Wani no Satsuki no omi. For Wani see Sect. LXII, Note 11. Satsuki is the old Japanese name of the fifth moon. ↩︎

401:3 Moribe thus paraphrases this Song: “The Monarch had met a girl carrying a spade in her hand, and as she was beautiful, wished to address her; but she ran off and hid on the hill-side, leaving her spade behind her. His words express a desire for five hundred spades like hers, with which to break down the hill-side and dig her out. . . . It is in joke that he talks of the maiden who was on the other side of the hill as being inside it.” That in ancient times all digging implements were not made of metal will be seen by reference to Sect. CXXIV, Note 9. ↩︎

401:4 Kanasuki no woko. ↩︎

401:1b p. 403 Said to be scarcely distinguishable from the keyaki (Zelkowa keaki) ↩︎

401:2b See Sect. LXXXIX, Note 7. ↩︎