© 2024 Carmelo Martínez

© 2024 Urantia Association of Spain

¶ 1. Presentation

On many inhabited worlds in this universe, our planet is known as the world of the cross. The reason is obvious: Michael of Nebadon, incarnated as Jesus of Nazareth, was crucified on April 7, 30 AD, to the astonishment and grief of all celestial intelligences. After his death, his body was placed in a nearby tomb, and on the third day, Sunday, April 9, 30 AD, a group of believing women who were about to properly embalm his body found that the stones enclosing the tomb had been moved, leaving access open. One of the women entered and saw that Jesus’ body was no longer there.

Briefly summarized, these are the main facts of the death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth that have led to our planet being known as the world of the cross.

Christian tradition places the scene of this event at the site where the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands today, which is supposed to cover the rock on which Jesus was crucified and the nearby tomb where he was laid to rest.

I wonder if, in light of the information contained in The Urantia Book, this tradition can be maintained or if these events should be located elsewhere in Jerusalem. This paper aims to answer that question.

¶ 2. The walls of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a very ancient city; it is estimated to be at least 4,000 years old (although it was originally called Salem and shortly after, Jebus), and it appears to have always been walled.

Remains of a wall dating back some 4,000 years have been found. During the time of Machiventa Melchizedek, the site was already inhabited and was known as Salem (Machiventa was called “the sage of Salem”). Later, it was called Jebus. The remains found appear to date from this period.

In the 10th century BC David also walled it, and his son Solomon improved these fortifications and built the first temple.

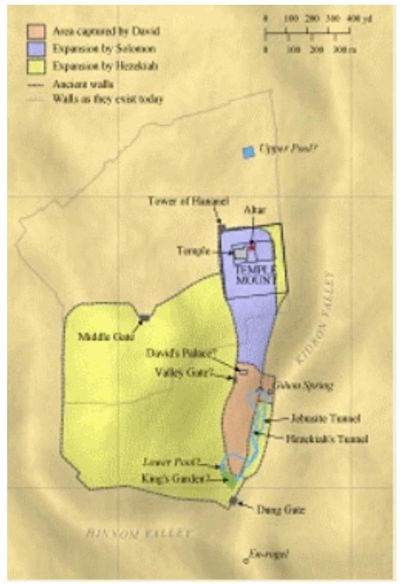

At the time of Jesus, there were two walls. The first and oldest is believed to have been built in the 8th century BC. This wall was destroyed during the Babylonian conquest and rebuilt four centuries later along with the construction of the Second Temple. Figure 1 is a representation of that wall as archaeologists believe it to have existed.

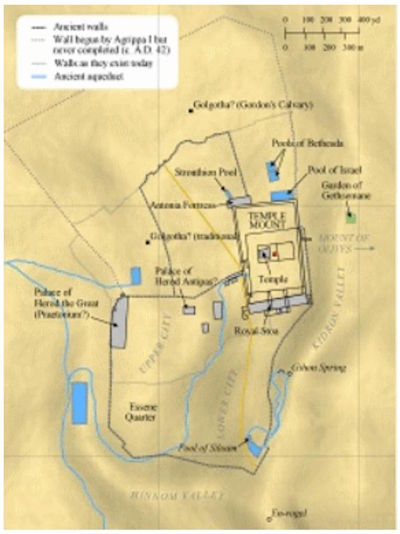

The Second Wall was built in the 2nd century BC and encompassed Mount Zion and the Temple Mount. There are several theories about how this second wall was laid out. Figure 2 represents the most widely accepted one, which we will use in this paper.

As can be seen, the location of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was outside the city walls in Jesus’ time.

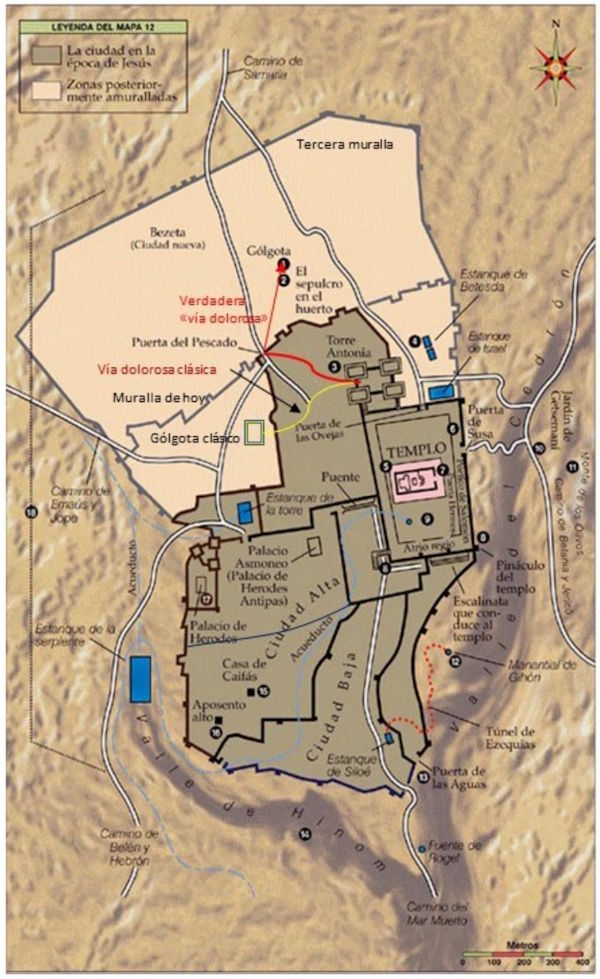

A few decades after Jesus’ death, the third wall was built to protect the new part of the city that had been gradually growing north of the existing walls. The Urantia Book refers to this area in UB 187:1.4: “…Beyond Golgotha were the villas of the rich…” Figure 3 shows the position of this wall, the uppermost one in this representation.

All of them, along with the city of Jerusalem itself, were completely destroyed in 70 AD by the Romans during the First Roman-Jewish War, also known as the “Great Jewish Revolt.”

Jerusalem lay in ruins for several decades until it was rebuilt by the Romans around the middle of the 2nd century under the name Aelia Capitolina, with the aim of erasing the memory of the ancient city and the Jewish revolt.

Throughout history, there were several other destructions and reconstructions, but finally, in the 16th century AD, the walls surrounding the so-called Old City of Jerusalem were built and have survived to this day. Figure 3 represents all the walls in the position they were in during the 16th century and would have been in had they existed then. The dark line in the Upper City represents the section of wall that complements the remaining black lines of the 16th-century wall still standing today around the Old City of Jerusalem.

Thanks to recent excavations, it is generally accepted that part of the 16th-century wall (the present-day wall) runs along the same route as the northern section of the second wall. We will return to this topic when we discuss the Damascus Gate.

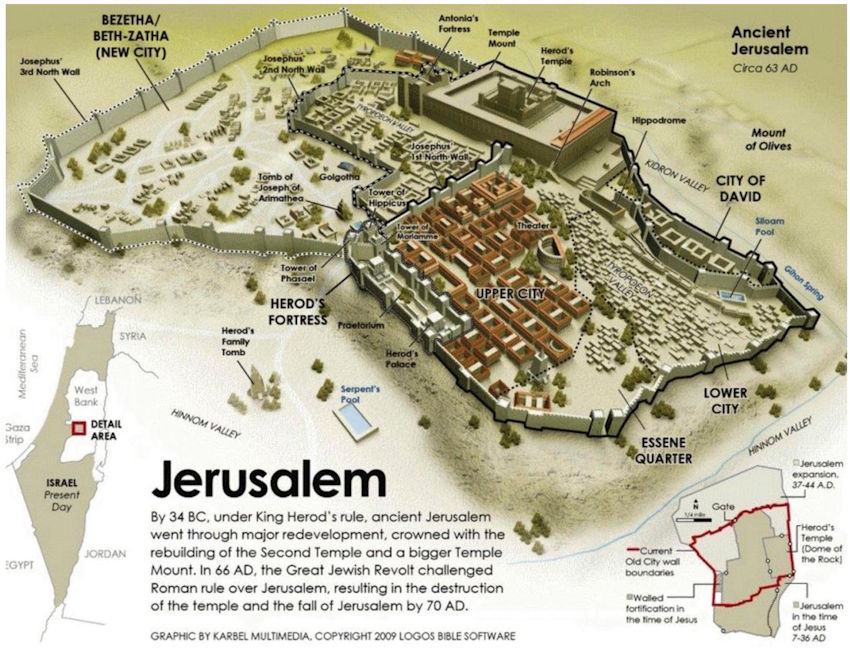

Figure 4 is a perspective representation of what the city of Jerusalem is believed to have looked like in the first century before it was razed by the Romans. In its lower right corner, a diagram shows the position of the walls surrounding the Old City today (in red) in relation to the first-century walls.

The second temple occupied a somewhat larger area than the Dome of the Rock esplanade, and the Antonia fortress was roughly in the area of the Sisters of Zion convent. See Figure 15. (Google Earth is very helpful for locating the different sites on a map.)

¶ 3. The Damascus Gate

The exit from the city to the north of the second wall was called the Fish Gate because it was through this gate that those who brought in fish from the Sea of Galilee entered (see figure 3).

The Fish Gate is actually the Damascus Gate, but it wasn’t known by that name until centuries later. As will be seen below, the Fish Gate/Damascus Gate has always been in the same place. The revelators refer to that gate as Damascus so that we can more easily identify it with the Damascus Gate of today, because “the Fish Gate” has been a term that has been completely out of use for many centuries.

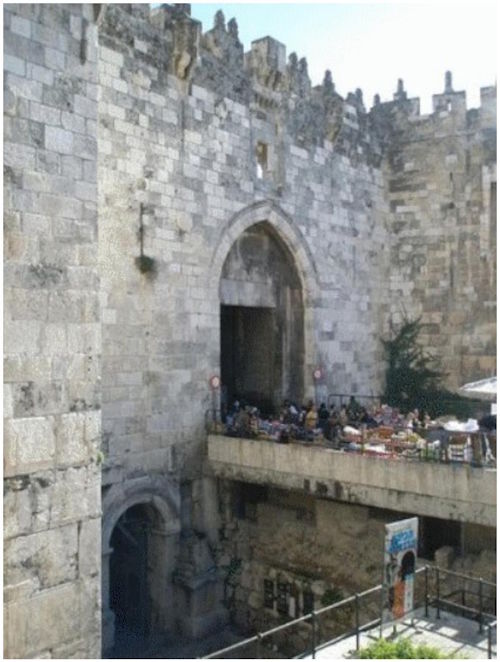

The present-day Damascus Gate was built in the 16th century. See figure 5.

Excavations have been carried out in the area and it has been found that this Damascus Gate covers an older gate, as seen on the left in Figure 6.

This oldest gate dates back to the 2nd century and was built around 135 as part of the reconstruction of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) by the Emperor Hadrian.

But this older gate is itself a reconstruction of an even older gate that already existed in Jesus’ time, a gate that was destroyed in 70 AD along with the rest of the walls and the city of Jerusalem. Recent excavations have found remains of this gate and the second wall beneath this section of the present-day wall.

Therefore, it is argued that the Fish Gate/Damascus has always been in the same place and that the configuration of the second wall was very similar to that of Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 7 represents a view of this 2nd century gate discovered after excavations carried out in the area of the Damascus Gate.

The existence and approximate position of the Damascus Gate is one of the keys to discovering the site of the crucifixion, although its exact position is less relevant.

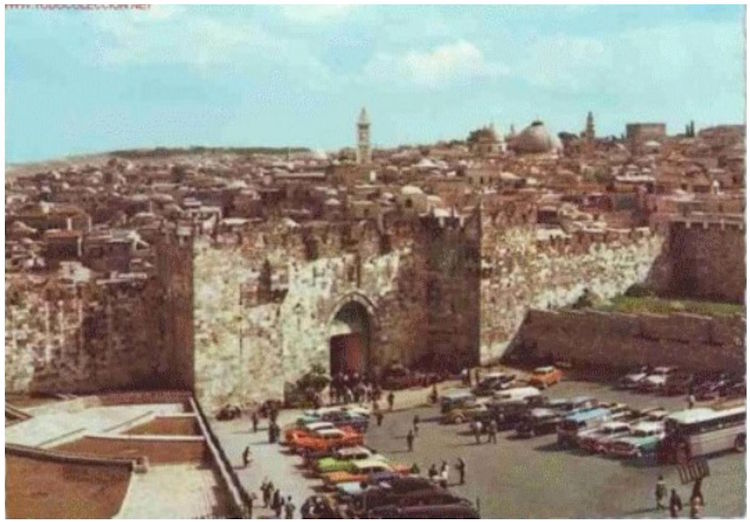

As a curiosity, I add a photo of the Damascus Gate from a period before the excavations began (fig. 8).

¶ 4. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Christian tradition identifies the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the place where Jesus was crucified and later buried. This tradition dates back to the fourth century (around 325). Emperor Constantine, the first Christian Roman ruler, was in power in Rome at the time. His mother, Empress Helena, learned of the deplorable state of the “holy places” and decided to travel to Jerusalem to find out.

He asked the Christians of Jerusalem where Jesus died and they pointed out a place where a pagan temple dedicated to the goddess Venus stood at that time, built in the 2nd century when Jerusalem was rebuilt as Aelia Capitolina.

He ordered the demolition of this pagan temple and the construction of a Christian church in its place.

It is said that when they demolished the Temple of Venus, they found three crosses, one of which produced miraculous cures and the other two did not. They thus identified Jesus’ cross, the so-called True Cross. The story is clearly a myth because the Romans did not crucify people on complete, one-piece crosses. First, the vertical pole was prepared and firmly nailed to the crucifixion site, and the convict carried to that spot the smaller horizontal pole, which was fixed to the top of the horizontal pole with the convict already nailed to it.

The tradition of the Holy Sepulchre originated three hundred years after the crucifixion. It might be thought that the early Christians passed on their knowledge of the crucifixion site from generation to generation, but it must be kept in mind that there were very few followers of Jesus in Jerusalem, and therefore they knew about the place designated by the Romans for that punishment. It is not surprising that this knowledge could have been distorted over the centuries. For centuries, Jews were not allowed to settle in Jerusalem, or even visit the city, so they were also unable to pass on the possible tradition of the crucifixion site.

There are very few indications in the Gospels about the location of this place. Only John (who witnessed much of the crucifixion and was one of those who carried Jesus’ body and participated in his embalming and burial) gives any further information in John 19:41:

“Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had yet been laid.”

Excavations have been carried out in the subsoil of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the rock of Golgotha is believed to have been discovered, and recently, the tomb of Jesus was discovered nearby. Other tombs from the first century have also been found.

¶ 5. Gordon’s Calvary and the Garden Tomb

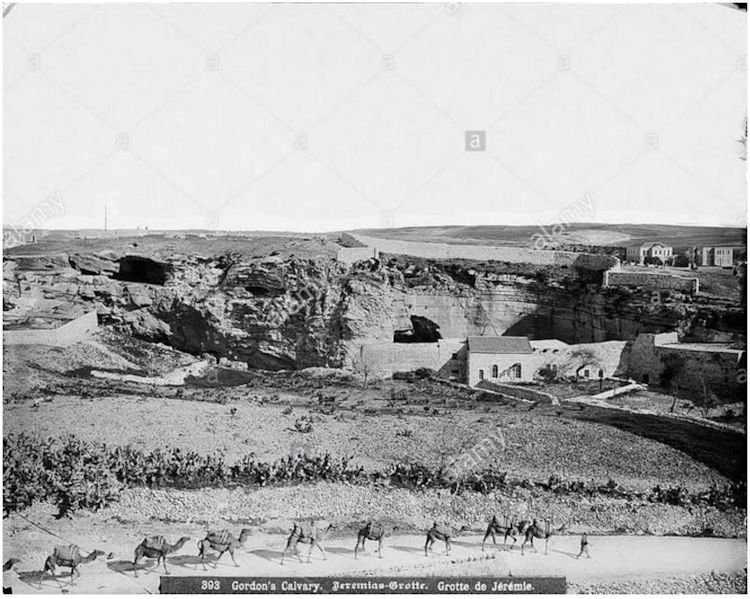

Not all Christians accept this tradition. In the 19th century, a Dresden theologian, an expert on biblical themes, based his argument on earlier studies to claim that Golgotha is a rocky outcrop located just outside Damascus Gate. A few years later, an English soldier, Charles Gordon, traveled to Jerusalem. One day, strolling around the outcrop north of Damascus Gate, he observed a curious phenomenon on a rock face: the appearance of a skull (see Figure 9).

Nearby he found a grave in a garden and, as he was familiar with the Dresden theologian’s theory, he became convinced that those were the “holy places.”

Since then, the rock has been known as Gordon’s Calvary.

The fact that the rock today has the appearance of a skull is in no way proof that this is Golgotha (the place of the skull) because the passage of 20 centuries, erosion and rain have undoubtedly changed the formations of the rock, so it is impossible to ensure that this appearance of a skull was there in the 1st century.

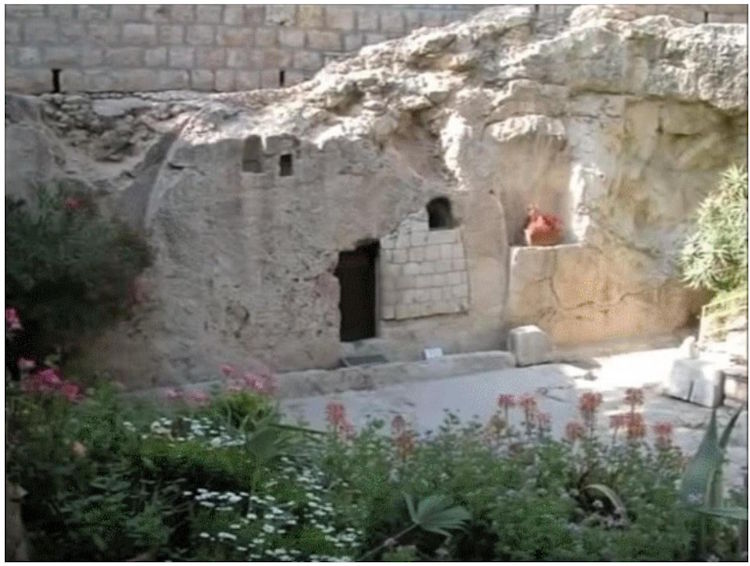

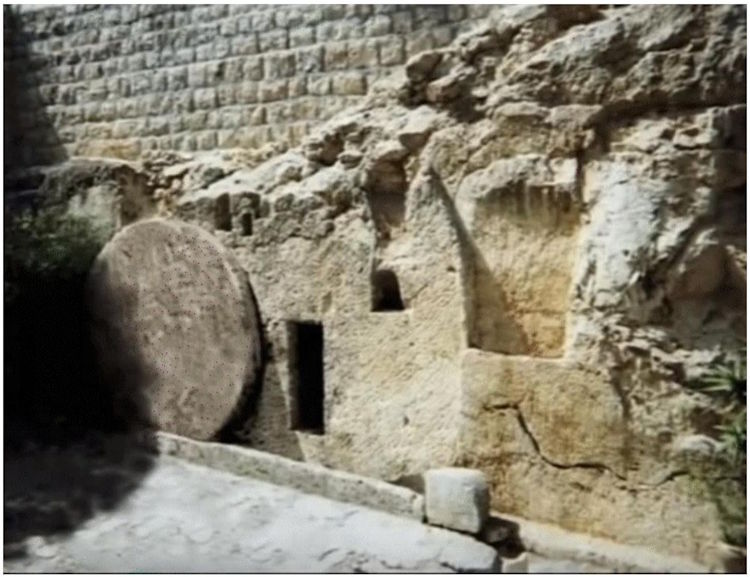

Very close to the north and west there is a garden inside which there is a tomb excavated in the rock (figure 12).

This tomb was hidden under a layer of earth deposited over the centuries as can be seen in Figure 13.

The tomb was discovered in 1867 and unearthed in 1891. Gordon visited it in 1882 on the aforementioned trip to Jerusalem. He became convinced that it was Jesus’s tomb because it matched the position of what is now Gordon’s Golgotha.

In 1894 Gordon formed the Garden Grave Society and with the donations he received he purchased the land surrounding the grave.

The garden of today is of course not the garden of Jesus’ time, but excavations and unearthings in the area have discovered that there had been a garden in the area in the 1st century, actually an orchard of fruit trees and edible plants, because they found the remains of a huge cistern for storing water in winter and using it for irrigation in summer, and of a winepress, both dating from the 1st century.

The Garden Tomb is now enclosed by a brick wall that was once made of the same rock. It is believed that over the years it has undergone several renovations, and the original rock wall was probably demolished at some point. Its probable original exterior appearance is shown in Figure 14.

¶ 6. Pilate’s Praetorium

As noted in both The Urantia Book and the Gospels, Jesus went to the place of his crucifixion from a building that was the praetorium where Pilate resided when he stopped in Jerusalem for Passover and where he judged the Master.

This building is usually considered to be the Antonia Tower, but some theories claim it was actually the palace of Herod the Great. According to The Urantia Book, this could not have been the palace because paragraph 185:4.1 begins by saying:

“When Herod Antipas was in Jerusalem he resided in the old Maccabean palace of Herod the Great…” UB 185:4.1

The palace was occupied by Herod, so it could not have been Pilate’s residence and therefore the Roman praetorium, since the praetorium was where the Roman authority of the place resided and the seat of its court of justice.

Furthermore, the location of Pilate’s residence is explicitly stated in 185:0.2:

“…This trial was arranged to take place in front of the praetorium, an addition to the fortress of Antonia, where Pilate and his wife made their headquarters when stopping in Jerusalem.” UB 185:0.2

And in 187:1.1 it is noted from where the procession that took Jesus and the two bandits to Golgotha departed:

“Before leaving the courtyard of the praetorium, the soldiers placed the crossbeam on Jesus’ shoulders. It was the custom to compel the condemned man to carry the crossbeam to the site of the crucifixion. Such a condemned man did not carry the whole cross, only this shorter timber. The longer and upright pieces of timber for the three crosses had already been transported to Golgotha and, by the time of the arrival of the soldiers and their prisoners, had been firmly implanted in the ground.” UB 187:1.1

¶ 7. The highway of Samaria and Damascus

The Urantia Book refers to that path in 187:14:

“…but on this day they went by the most direct route to the Damascus gate, which led out of the city to the north, and following this road, they soon arrived at Golgotha, the official crucifixion site of Jerusalem.” UB 187:1.4

There was a road leading north from the Damascus Gate. To the north was Samaria, and given the name of the gate, its ultimate destination would be Damascus.

I haven’t found any information on where this road ran for the first few meters from the Damascus Gate, but there are some early 20th-century photos showing a roadway that runs alongside the esplanade of Golgotha. Considering that the layout of many main roads has remained the same for centuries until the modern era, and that countless highways and motorways today follow the layout of Roman roads from when Rome conquered Hispania, I will assume that the roadway Jesus traveled with the crossbar of the cross had a layout similar to that in the early 20th-century photo in Figures 15-0 and 15-1.

¶ 8. From the Praetorium to Golgotha

Based on that information and what The Urantia Book says, we will locate the different places where Jesus passed on his way to crucifixion, where he was crucified, and where he was buried.

We will begin with the journey taken by the procession that carried Jesus and the two thieves from the Praetorium to Golgotha.

Paragraph 187:0.3 describes the departure of the praetorium:

“It was just before nine o’clock this morning when the soldiers led Jesus from the praetorium on the way to Golgotha. They were followed by many who secretly sympathized with Jesus, but most of this group of two hundred or more were either his enemies or curious idlers who merely desired to enjoy the shock of witnessing the crucifixions. Only a few of the Jewish leaders went out to see Jesus die on the cross. Knowing that he had been turned over to the Roman soldiers by Pilate, and that he was condemned to die, they busied themselves with their meeting in the temple, whereat they discussed what should be done with his followers.” UB 187:0.4

The key paragraph to understand this journey is 187:1.4, which says:

“Ordinarily, it was the custom to journey to Golgotha by the longest road in order that a large number of persons might view the condemned criminal, but on this day they went by the most direct route to the Damascus gate, which led out of the city to the north, and following this road, they soon arrived at Golgotha, the official crucifixion site of Jerusalem. Beyond Golgotha were the villas of the wealthy, and on the other side of the road were the tombs of many well-to-do Jews.” UB 187:1.4

These “villas of the rich” were the northern expansion of Jerusalem, an area that was protected by the third wall two decades after Jesus’ death.

I calculated the distance from the Praetorium to Golgotha using Google Earth and it turned out to be about 600 meters, of which 400 meters were inside the walls (from the Praetorium to the Damascus Gate) and 200 meters outside (from the Damascus Gate to the crucifixion site). From the book, it can be deduced that it took about ten minutes: they left “Just before nine this morning” and arrived when it was “a little after nine” (187:1.11).

Figures 15 and 16 show the different places referred to in this work on an image of the old city today taken from Google Earth.

We can follow in Figure 3 (more schematically) and in Figure 15 in more detail the route of the procession of 12 soldiers with their captain, Jesus, and the two bandits: they left the Praetorium (the extension of the Antonia Tower) and headed toward the Damascus Gate, which was the most direct way to reach Golgotha. They presumably chose to take the streets leading to the gate by the shortest route. It was in these streets that the women wept for Jesus.

Once they passed through the Damascus Gate, they continued along the road that started there and headed north to Damascus, passing through Samaria. Golgotha must have been close because “they arrived quickly” (fig. 16), perhaps less than five minutes.

According to this, the place of the crucifixion can only be the rock called Gordon’s Golgotha (figures 10 and 11), which is located a short distance north of the Damascus Gate.

It cannot be in the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre because to do so they would have had to go west and south as can be seen in Figure 2.

Although this church fulfills the condition of being (in Jesus’ time) outside the city but close to the wall, it is located to the west and south of the Antonia fortress, and not to the north.

¶ 9. The place of the crucifixion

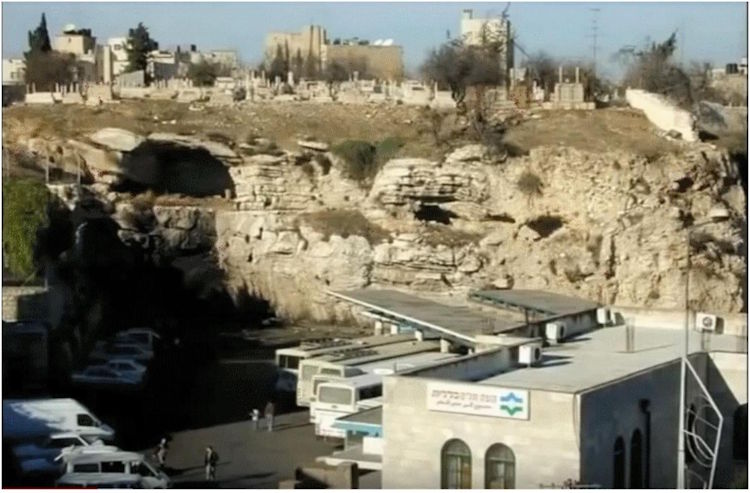

The crucifixion is usually presented at the top of Golgotha, however, another position at the base of the rock is more likely.

The Romans used crucifixion as a punishment for non-Romans and with the intent to teach a lesson. Therefore, it would make little sense for this “official place of crucifixion” to be far from the beaten path or in a location difficult to access. Climbing to the top of a rock undoubtedly has a deterrent effect on many people. Many “idle onlookers who merely desired to enjoy the shock of witnessing crucifixions” (187:0.3) would have given up witnessing them if they had had to struggle to climb to the top of Golgotha.

Furthermore, the duration of the journey was short, as I mentioned above, and it would have been longer if the condemned had had to climb to the top of Golgotha carrying the wood of the cross, especially Jesus, who was exhausted.

There is a further indication of the place of the crucifixion in 187:3.3:

«Many who passed by shook their heads and ridiculed him, saying: “You who would have destroyed the temple and rebuilt it in three days, save yourself.” UB 187:3.3

This indicates that it was near a road, the highway of Samaria and Damascus most certainly, which would certainly have been very busy, which increased the sobering effect of the crucifixion.

In Figure 11, you can see a platform at the base of the rock with some buses and trucks; this was probably the site of the crucifixion in the first century. A bus station stands there today. So we can humorously state (and with your permission, Master) that Jesus of Nazareth was crucified in what, nineteen hundred years or so later, would be the Jerusalem station for the West Bank (Figs. 17, 18, 19, 29, and 21).

This location is indicated on the map in Figures 15 and 16. It can be seen that it is close (about 100 meters) to the so-called Garden Tomb.

¶ 10. The tomb of Jesus

The indications that the book gives us about this tomb are in 188:1.2:

“A crucified person could not be buried in a Jewish cemetery; there was a strict law against such a procedure. Joseph and Nicodemus knew this law, and on the way out to Golgotha they had decided to bury Jesus in Joseph’s new family tomb, hewn out of solid rock, located a short distance north of Golgotha and across the road leading to Samaria.” UB 188:1.2

The Garden Tomb is located north and slightly west of the probable crucifixion site, a short distance (about 100 meters) and across “the highway that led to Samaria.” Its entrance faces southeast, which also corresponds to the book’s statement in 189:4.6:

“This tomb of Joseph was in his garden on the hillside on the eastern side of the road, and it also faced toward the east.” UB 189:4.6

This statement seems contradictory, but if analyzed in detail, not only is it not, but it provides an additional orographic detail. The crucifixion site was on the east side of the Samaria highway, and if the tomb was on the other side, it means it was on the west side, which seems to contradict the aforementioned statement. But what is being said is that “the slope on the east side of the highway” continued to the west side of the road where the garden (on a slope) and the tomb were; that is, the highway crossed that slope.

We have already noted above that installations from the 1st century have been found in the vicinity of the Garden Tomb, which indicate that there was once a garden there.

So it seems more than likely that what is now called the Garden Tomb was the place where Jesus was buried.

This tomb has been used and remodeled (carved and recarved) several times over the past 20 centuries. One indication of this is that it lacked a frontal enclosing wall when it was unearthed (that wall has been rebuilt with bricks). There is some certainty that it was used in the Byzantine period and was even a place of worship. All of this makes it difficult to know what it looked like in the first century.

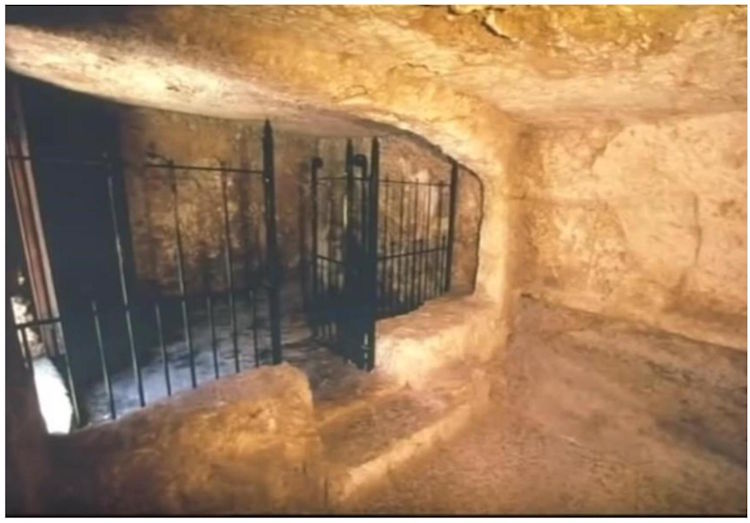

Today it has two chambers: an entrance and a burial chamber. Figure 22 is a photo taken from inside the burial chamber.

Behind the gate is the entrance chamber and on its left side is the entrance.

Figure 23 is a detail of the burial hole in the ground. It is a photo taken from the entrance side.

Let’s see what The Urantia Book says about the inside of the tomb.

“They carried the body into the tomb, a chamber about ten feet square, where they hurriedly prepared it for burial. The Jews did not really bury their dead; they actually embalmed them. Joseph and Nicodemus had brought with them large quantities of myrrh and aloes, and they now wrapped the body with bandages saturated with these solutions. When the embalming was completed, they tied a napkin about the face, wrapped the body in a linen sheet, and reverently placed it on a shelf in the tomb.” UB 188:1.4

I don’t believe that platform was at ground level, which is where the body hole is now visible. The following quote from 189:4.6 corroborates this:

“…By this hour there was just enough of the dawn of a new day to enable Mary to look back to the place where the Master’s body had lain and to discern that it was gone. In the recess of stone where they had laid Jesus, Mary saw only the folded napkin where his head had rested and the bandages wherewith he had been wrapped lying intact and as they had rested on the stone before the celestial hosts removed the body. The covering sheet lay at the foot of the burial niche.” UB 189:4.6

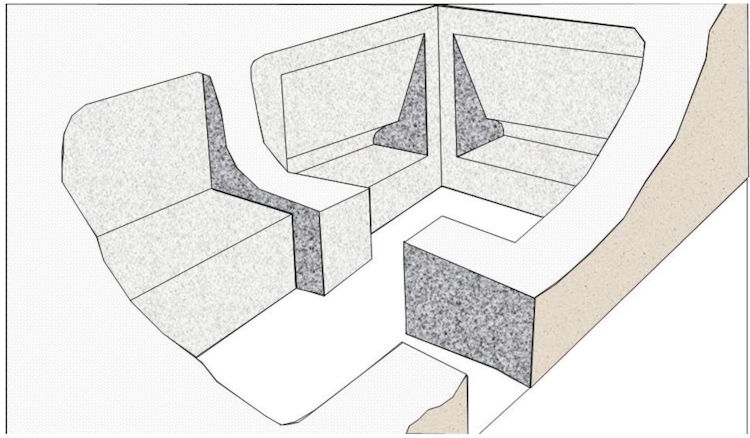

Figure 24 shows a recreation of the interior of a first-century tomb. It has been drawn with two niches carved into the stone, but it is possible that only the niche on the left of the image was present, given the current state of the Garden Tomb. Jesus was placed in the one on the left, which is visible from the entrance, from where the bandages could be seen and the sheet falling to the ground at the foot of the niche.

Probably when they arrived at the tomb with Jesus’ body, they embalmed it on the platform of the entrance chamber and then placed it in the aforementioned niche.

¶ 11. The closing of the tomb and Pilate’s seals

Regarding the closing of the tomb, The Urantia Book says in 188:1.5:

“After placing the body in the tomb, the centurion signaled for his soldiers to help roll the doorstone up before the entrance to the tomb. The soldiers then departed for Gehenna with the bodies of the thieves while the others returned to Jerusalem, in sorrow, to observe the Passover feast according to the laws of Moses.” UB 188:1.5

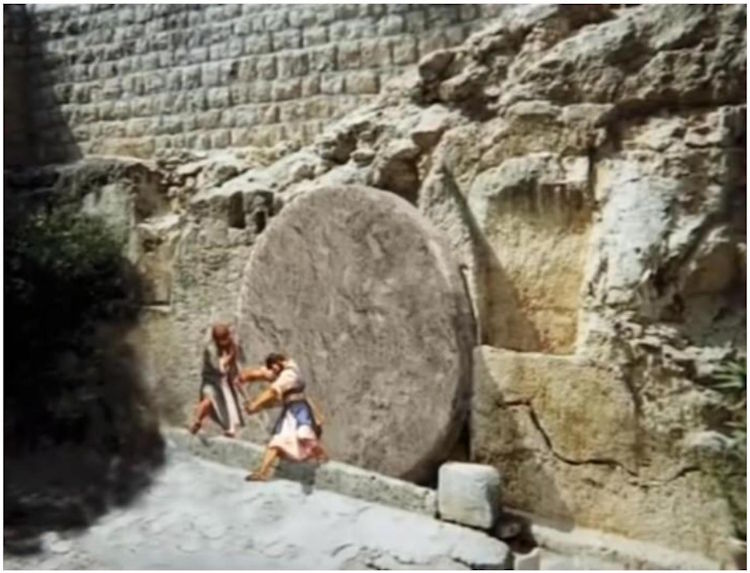

In Figure 14, we see the probable exterior appearance of the Garden Tomb, with the end stone still in place and the channel through which it rolled to close the entrance. In Figure 25, we see the tomb now closed.

But there was more.

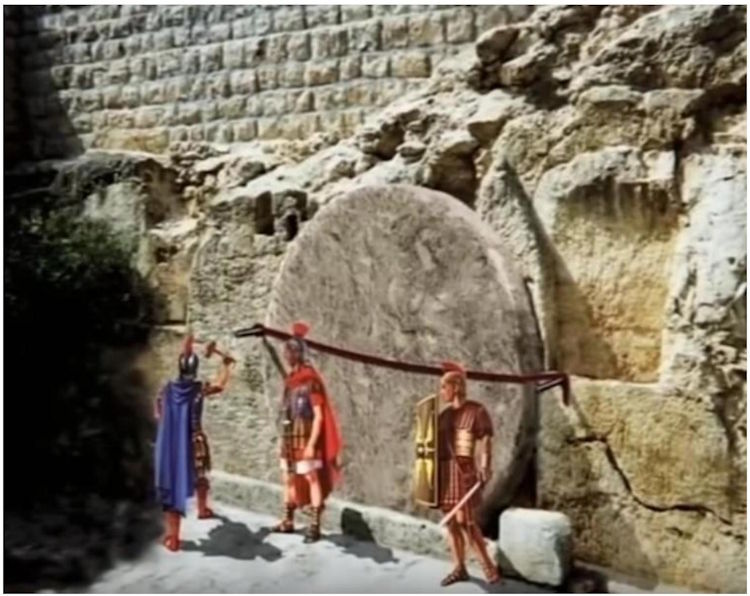

“…This meeting ended with the appointment of a committee of Sanhedrists who were to visit Pilate early the next day, bearing the official request of the Sanhedrin that a Roman guard be stationed before Jesus’ tomb to prevent his friends from tampering with it. Said the spokesman of this committee to Pilate: “Sir, we remember that this deceiver, Jesus of Nazareth, said, while he was yet alive, ‘After three days I will rise again.’ We have, therefore, come before you to request that you issue such orders as will make the sepulchre secure against his followers, at least until after the third day. We greatly fear lest his disciples come and steal him away by night and then proclaim to the people that he has risen from the dead. If we should permit this to happen, this mistake would be far worse than to have allowed him to live.”” UB 188:2.2

“When Pilate heard this request of the Sanhedrists, he said: “I will give you a guard of ten soldiers. Go your way and make the tomb secure.” They went back to the temple, secured ten of their own guards, and then marched out to Joseph’s tomb with these ten Jewish guards and ten Roman soldiers, even on this Sabbath morning, to set them as watchmen before the tomb. These men rolled yet another stone before the tomb and set the seal of Pilate on and around these stones, lest they be disturbed without their knowledge. And these twenty men remained on watch up to the hour of the resurrection, the Jews carrying them their food and drink.” UB 188:2.3

It is not known what this “seal of Pilate” consisted of, but figure 26 represents what that seal on the first stone could have been.

It’s safe to assume that the second stone, certainly smaller and probably placed opposite the other, resting on it, had a similar seal. I suppose the edges of the stones were marked to detect any tampering.

In the Garden Tomb, a piece of iron was found embedded in the rock at the approximate position of the left nail holding the seal of the large stone. Analysis indicates it is a piece of iron from the first century and probably part of Pilate’s seal.

The exaggerated nature of these measures to ensure the tomb’s seal remained intact is surprising. It seems that the Sanhedrin is genuinely terrified of the powers of Jesus of Nazareth, and not so much of the actions of his disciples.

Naturally, the midwayers had no problem breaking the seals and moving the stones until the entrance to the tomb was clear.

This is what paragraph 189:2.4 says about the operation of the intermediates:

“As they made ready to remove the body of Jesus from the tomb preparatory to according it the dignified and reverent disposal of near-instantaneous dissolution, it was assigned the secondary Urantia midwayers to roll away the stones from the entrance of the tomb. The larger of these two stones was a huge circular affair, much like a millstone, and it moved in a groove chiseled out of the rock, so that it could be rolled back and forth to open or close the tomb. When the watching Jewish guards and the Roman soldiers, in the dim light of the morning, saw this huge stone begin to roll away from the entrance of the tomb, apparently of its own accord—without any visible means to account for such motion—they were seized with fear and panic, and they fled in haste from the scene. The Jews fled to their homes, afterward going back to report these doings to their captain at the temple. The Romans fled to the fortress of Antonia and reported what they had seen to the centurion as soon as he arrived on duty.” UB 189:2.4

The arrangement of the stones after the intervention of the intermediates can be deduced from the following paragraphs.

“It was about half past three o’clock when the five women, laden with their ointments, arrived before the empty tomb. As they passed out of the Damascus gate, they encountered a number of soldiers fleeing into the city more or less panic-stricken, and this caused them to pause for a few minutes; but when nothing more developed, they resumed their journey.” UB 189:4.5

“They were greatly surprised to see the stone rolled away from the entrance to the tomb, inasmuch as they had said among themselves on the way out, “Who will help us roll away the stone?” They set down their burdens and began to look upon one another in fear and with great amazement. While they stood there, atremble with fear, Mary Magdalene ventured around the smaller stone and dared to enter the open sepulchre. This tomb of Joseph was in his garden on the hillside on the eastern side of the road, and it also faced toward the east. By this hour there was just enough of the dawn of a new day to enable Mary to look back to the place where the Master’s body had lain and to discern that it was gone. In the recess of stone where they had laid Jesus, Mary saw only the folded napkin where his head had rested and the bandages wherewith he had been wrapped lying intact and as they had rested on the stone before the celestial hosts removed the body. The covering sheet lay at the foot of the burial niche.” UB 189:4.6

It is clear that the large stone had rolled to its original position, leaving the entrance open, and it appears that the small one simply fell to the ground in front of the entrance because Mary “ventured around the smaller stone” that was blocking the way to enter.

¶ 12.Epilogue

Neither faith in Jesus nor his incomparable teachings depend in any way on the circumstances of his life and death, nor on the places where he lived and suffered, or where he taught.

This work is not intended to awaken or rekindle anyone’s faith, but rather to give images to the episode of his crucifixion, burial, and resurrection. Some people, like me, when we read a story, like to imagine what the place where it happened was like and what other circumstances surrounded it.

This work aims to provide images of what is described in The Urantia Book about the final episode of the Master’s life and thus help the imagination of those who read documents 187, 188 and 189, which, by the way, I recommend rereading.