© 2018 Halbert Katzen, JD

Prepared by Halbert Katzen, J.D. [10/25/11]

¶ Early Migration To China Summary

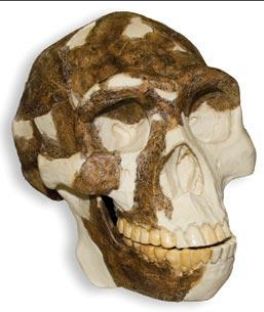

About 25 miles southwest of Beijing, China is an archaeological site at Zhoukoudian that is of particular interest to anthropologists. UNESCO (the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) placed this site on the World Heritage List in 1987 because it is an especially abundant source of early humanoid artifacts, commonly referred to as Peking Man.

Accurately dating human fossils from the Zhoukoudian site, however, has been difficult. In 2008 new and more exacting dating techniques were applied to the sediment layers where the bones were found. The results indicate that the fossils are around 200,000 years older than previous estimations of approximately 550,000 years. The new dating places these fossils in a significantly colder environment due to ice age activity that occurred 750,000 years ago.

Additionally, a recent re-evaluation of hand axes found at the site reveal a higher degree of sophistication in tool making than previously thought. This discovery indicates that these early humans were more skilled at hunting and slaughtering animals than anthropologists originally hypothesized.

These recent refinements in research technique provide us with an understanding of early migration to China that is more closely aligned with the recounting of early human activity in the region published in 1955 in The Urantia Book.

The Early Migration to China Report is the third UBtheNEWS report on primitive man during this time period. Reading the Creating Fire Report and then the Early Migration to Britain Report before reading this report allows you to develop a more chronological appreciation of the reports on primitive human beings.

¶ Early Migration To China Review

On March 11, 2009 Paul Rincon, a science reporter for BBC News, published an article that reviews the research results from the Zhoukoudian site completed in 2008 and provides some history on the subject. His article states:

Iconic ancient human fossils from China are 200,000 years older than had previously been thought, a study shows.

The new dating analysis suggests the “Peking Man” fossils, unearthed in the caves of Zhoukoudian, are some 750,000 years old.

The discovery should help define a more accurate timeline for early humans arriving in North-East Asia.

A US-Chinese team of researchers has published its findings in the prestigious journal Nature.

The cave system of Zhoukoudian, near Beijing, is one of the most important Paleolithic sites in the world.

Between 1921 and 1966, archaeologists working at the site unearthed tens of thousands of stone tools and hundreds of fragmentary remains from about 40 early humans.

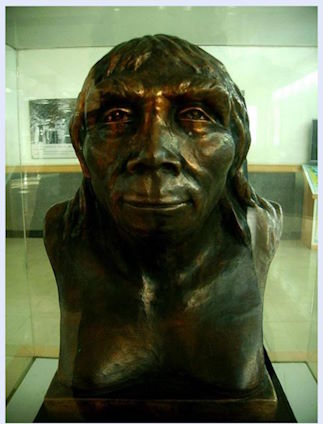

Paleontologists later assigned these members of the human lineage to the species Homo erectus.

. . .

Experts have tried various methods over the years to determine the age of the remains. But they have been hampered by the lack of suitable techniques for dating cave deposits such as those at Zhoukoudian.

Now, Guanjun Shen, from Nanjing Normal University in China, and colleagues have applied a relatively new method to the problem.

This method is based on the radioactive decay of unstable forms, or isotopes, of the elements aluminium and beryllium in quartz grains. This enabled them to get a more precise age for the fossils.

The results show the Peking Man fossils came from ground layers that were 680,000780,000 years old, making them about 200,000 years older than had previously been believed.

Comparisons with other sites show that Homo erectus survived successive warm and cold periods in northern Asia.

Researchers Russell Ciochon and E Arthur Bettis III, from the University of Iowa, US, believe these climatic cycles may have caused the expansion of open habitats, such as grasslands and steppe. These environments would have been rich in mammals that could have been hunted or scavenged by early humans. [1]

“The human race is almost one million years old,” according to The Urantia Book.[2] But the genetically progressive mutation that started the human race, first appearing in a set of twins, while sufficient for the development of primitive human mind, was not sufficient to support much in terms of primitive human civilization. This first primitive race of human beings are termed Andonites in The Urantia Book. In reviewing the history of humanity, the authors recount that a significant genetic improvement occurred after our first 150,000 years (850,000 years ago). This event involves a tribe of primitive human beings that lived in the general area where humanity first got started. The Urantia Book refers to them as the “Badonan” tribes.

To the east of the Badonan peoples, in the Siwalik Hills of northern India, may be found fossils that approach nearer to transition types between man and the various prehuman groups than any others on earth.

850,000 years ago the superior Badonan tribes began a warfare of extermination directed against their inferior and animalistic neighbors. In less than one thousand years most of the borderland animal groups of these regions had been either destroyed or driven back to the southern forests. This campaign for the extermination of inferiors brought about a slight improvement in the hill tribes of that age. And the mixed descendants of this improved Badonite stock appeared on the stage of action as an apparently new people — the Neanderthal race.[3]

Note how the authors provide a clue about where we can make important new discoveries related to the human fossil record. These types of clues frequently appear in the text.

The authors of The Urantia Book define the Neanderthal race on their own terms, a definition different from contemporary usage. This is just one example of how the authors encourage us to use terminology in specific ways. (To support the study of human evolution from a Urantia Book perspective, in 2011 UBtheNEWS published the first Urantia Book-based taxonomy.)[4]

After providing this new definition of the Neanderthal race, The Urantia Book goes on to describe their activities and migrations.

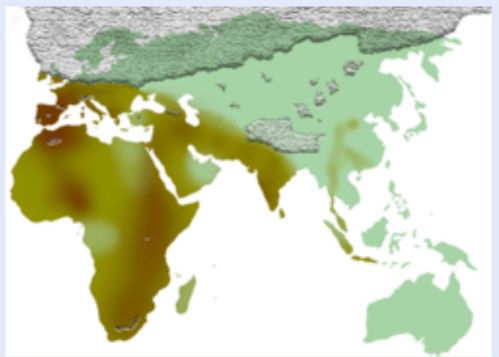

The Neanderthalers were excellent fighters, and they traveled extensively. They gradually spread from the highland centers in northwest India to France on the west, China on the east, and even down into northern Africa. They dominated the world for almost half a million years until the times of the migration of the evolutionary races of color.[5]

The Urantia Book depicts the Neanderthal race as one that “traveled extensively” and “dominated the world.” The conclusions reached in 2008 by the US-Chinese research team are more closely aligned by about 200,000 years with The Urantia Book’s depiction of this time period. Their research came more than fifty years after The Urantia Book was published. The new techniques of advanced research performed by this team provide relatively accurate dating for the first time. The abstract of their report states:

The age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus, commonly known as ‘Peking Man’, has long been pursued, but has remained problematic owing to the lack of suitable dating methods. Here we report cosmogenic 26 Al/10Be burial dating of quartz sediments and artefacts from the lower strata of Locality 1 in the southwestern suburb of Beijing, China, where early representatives of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus were discovered. This study marks the first radioisotopic dating of any early hominin site in China beyond the range of mass spectrometric U-series dating. The weighted mean of six meaningful age measurements, 0.77 ± 0.08 million years (Myr, mean ± s.e.m.), provides the best age estimate for lower cultural layers 7-10. Together with previously reported U-series dating of speleothem calcite3 and paleomagnetic stratigraphy4, as well as sedimentological considerations, these layers may be further correlated to S6—S7 in Chinese loess stratigraphy or marine isotope stages (MIS) 17—19, in the range of ∼ 0.68 to 0.78 Myr ago. These ages are substantially older than previously supposed and may imply early hominin’s presence at the site in northern China through a relatively mild glacial period corresponding to MIS 18.[6]

The final comments in the abstract pertaining to the “mild glacial period” are harmonious with the description of early human history provided in The Urantia Book, indicating that the more advanced primitive humans preferred the colder climates as a way to protect themselves from the genetically inferior primitive humans and simians that tended to prefer more salubrious climates.

Primitive man made his evolutionary appearance on earth [in the general area of Afghanistan] a little less than one million years ago, and he had a vigorous experience. He instinctively sought to escape the danger of mingling with the inferior simian tribes. But he could not migrate eastward because of the arid Tibetan land elevations, 30,00o feet above sea level; neither could he go south nor west because of the expanded Mediterranean Sea, which then extended eastward to the Indian Ocean; and as he went north, he encountered the advancing ice. But even when further migration was blocked by the ice, and though the dispersing tribes became increasingly hostile, the more intelligent groups never entertained the idea of going southward to live among their hairy tree-dwelling cousins of inferior intellect.

Many of man’s earliest religious emotions grew out of his feeling of helplessness in the shut-in environment of this geographic situation – mountains to the right, water to the left, and ice in front. But these progressive Andonites would not turn back to their inferior tree-dwelling relatives in the south.

These Andonites avoided the forests in contrast with the habits of their nonhuman relatives. In the forests man has always deteriorated; human evolution has made progress only in the open and in the higher latitudes. The cold and hunger of the open lands stimulate action, invention, and resourcefulness. While these Andonic tribes were developing the pioneers of the present human race amidst the hardships and privations of these rugged northern climes, their backward cousins were luxuriating in the southern tropical forests of the land of their early common origin.

These events occurred during the times of the third glacier, the first according to the reckoning of geologists. The first two glaciers were not extensive in northern Europe. [7]

800,000 years ago game was abundant; many species of deer, as well as elephants and hippopotamuses, roamed over Europe. Cattle were plentiful; horses and wolves were everywhere. The Neanderthalers were great hunters …

The reindeer was highly useful to these Neanderthal peoples, serving as food, clothing, and for tools, since they made various uses of the horns and bones.[8]

750,000 years ago the fourth ice sheet was well on its way south. With their improved implements the Neanderthalers made holes in the ice covering the northern rivers and thus were able to spear the fish which came up to these vents. Ever these tribes retreated before the advancing ice, which at this time made its most extensive invasion of Europe.

In these times the Siberian glacier was making its southernmost march, compelling early man to move southward, back toward the lands of his origin. But the human species had so differentiated that the danger of further mingling with its nonprogressive simian relatives was greatly lessened.

700,000 years ago the fourth glacier, the greatest of all in Europe, was in recession; men and animals were returning north.[9]

In reference to the Neanderthal race, The Urantia Book also indicates that these primitive peoples were skilled at making the more advanced types of hand axes.

They had little culture, but they greatly improved the work in flint until it almost reached the levels of the days of Andon [Andon and Fonta are the names of the first two human beings]. Large flints attached to wooden handles came back into use and served as axes and picks.[10]

While still living with his parents, Andon had fastened a sharp piece of flint on the end of a club, using animal tendons for this purpose …[11]

The invention of weapon tools enabled man to become a hunter and thus to gain considerable freedom from food slavery. A thoughtful Andonite who had severely bruised his fist in a serious combat rediscovered the idea of using a long stick for his arm and a piece of hard flint, bound on the end with sinews, for his fist. Many tribes made independent discoveries of this sort, and these various forms of hammers represented one of the great forward steps in human civilization.[12]

The above commentary is consistent with more recent re-examinations of the artifacts found at the archaeological sites in China. These re-examinations occurred because the date of the Peking Man site was pushed back by 200,000 years. An April 28, 2011 article at history.com reports:

Homo erectus groups living in China 700,000 years ago may have survived in cold climates by fashioning sophisticated weapons such as spears for hunting and butchering animals. A new study of artifacts from China’s famous Zhoukoudian caves suggests that these early hominids were smarter and more adept than previously thought.

In 1918, archaeologists discovered some of the first specimens of Homo erectus, known as Peking Man, in the fossil-rich Zhoukoudian cave system near Beijing. Until recently, it was believed that the extinct hominid species, characterized by its upright stance and robust build, inhabited the area between 250,000 and 500,000 years ago, after the end of a glacial period that had significantly cooled northern China’s climate. But in 2009, new research revealed that Peking Man was much older, raising questions about how these primitive cave dwellers weathered the cold some 700,000 years ago.

Now, a team of scientists led by Chen Shen of the Royal Ontario Museum has reexamined artifacts found on the site and concluded that this particular Homo erectus group probably learned to survive by crafting sophisticated tools. “The new study suggests that Peking Man’s lithic [stone] technology was not simple as previously thought,” Shen and his colleagues wrote in an abstract to their recent paper, presented at a Society for American Archaeology conference in early April. “The microwear evidence indicates many typed tools were made for specific tasks related to processing animal substances.”

More specifically, Peking Man may have fashioned stone-tipped spears and used them to kill and butcher animals. The ability to construct “composition” tools-objects made of several different materials, such as wood and sharpened rock-indicates a level of dexterity and intelligence approaching that of modern humans. It is also the earliest evidence of such activity by early hominids in China, according to the abstract. Further research may shed light on whether these primitive tools were held together by sinew, sap or other substances.

Homo sapiens also adapted to cold climates by assembling weapons for hunting animals, which provided hides and fur to make clothing as well as a valuable food source in the absence of sufficient vegetation.[13]

Research performed by the Smithsonian Institute at a site further south in Bose, China adds additional support to both the timing and technology issues.

Since the 1940s, archeologists had been perplexed by what seemed to be a puzzle piece missing from the prehistoric record of East Asia — large stone tools like the Acheulean handaxes so common in Africa from about 1.6 million years ago, and in Europe beginning around 500,000 years ago. Carefully shaped multi-purpose handaxes were a major invention as early hominins refined their techniques for turning stone into technology. These were an advance over the more basic toolkit of the first toolmakers, which involved chipping flakes from usually small stone cores.

Making handaxes involved a more sophisticated understanding of a rock’s material structure and mechanical properties…

… As reported in the journal Science, our team found the oldest known large cutting tools in China, which resemble the handaxes of their African contemporaries in several ways. These include the intensive striking of flakes from both sides of large ovate rocks, typically river cobbles at Bose (rather than large flakes in Africa), and systematic shaping of a pointed or beveled end versus a rounded opposite end. The overall comparison indicates similar competence and skill in toolmaking in East Asia as occurred further west at the time of the Bose meteor impact, even though the large tool technology at Bose may have been independently developed.

The artifacts were excavated together with charred samples of wood and glassy microscopic shards and larger lumps known as tektites — once-molten pieces of Earth rock that radiated out over a vast area from Australia to China produced by an atmospheric impact and heating. The tools occurred solely in the tektite layer — a stroke of luck in that the tektites can be dated accurately — to 803,000 + 3,000 years. The association of the tektites, charred tree wood, and tools suggests that the forest fires triggered by the heat of the impact and the shower of tektites may have laid waste to the landscape and exposed the vast stone cobble beds, which were sources of suitable materials for making stone tools.

Although Paleolithic researchers are reluctant to give up the ‘Movius Line’ idea dividing east from west, its underlying basis — i.e., the inherent lack of skill of the toolmakers and the lack of a changing or challenging environment — is no longer supported. The cover of Science on March 3, 2000, highlighted these findings.[14]

Wikipedia provides an overview of the Movius Line and its significance:

The Movius Line is a theoretical line drawn across northern India first proposed by the American archaeologist Hallam L. Movius in 1948 to demonstrate a technological difference between the early prehistoric tool technologies of the east and west of the Old World.

Movius had noticed that assemblages of paleolithic stone tools from sites east of northern India never contained handaxes and tended to be characterized by less formal implements known as chopping tools. These were sometimes as extensively worked as the Acheulean tools from further west but could not be described as true handaxes. Movius then drew a line on a map of India to show where the difference occurred, dividing the tools of Africa, Europe and Western and Southern Asia from those of Eastern and Southeastern Asia.[15]

The Movius Line theory, which started in 1948 and has predominated for decades, is distinctly different than the depiction of early human history published in The Urantia Book in 1955. The Smithsonian Institute article directly acknowledges that the new discoveries require us to let go of the Movius Line theory regarding the early migration routes and technologies of primitive humans. Though it has taken over forty years, the continued study and development of the archaeological sites in China, in conjunction with the more open and cooperative relations between east and west, is starting to reveal a picture of early human activity more closely aligned with The Urantia Book’s portrayal of this time period.

¶ External links

- This report in UBTheNews webpage

- Other reports in UBTheNews webpage

- Topical Studies in UBTheNews webpage

- http://www.greatarchaeology.com/java_man.htm

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_erectus_pekinensis

- http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Java_man

- http://humanorigins.si.edu/research/asian-research/earliest-humans-china

- http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/dating

- http://www.nature.com/news/2009/090311/full/news.2009.149.html

- http://www.archaeologydaily.com/news/20090312737/The-Date-of-Birth-for-quotPeking-ManquotGets-Pushed-Back-200000-Years.html

- http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/80beats/2009/03/11/the-date-of-birth-for-peking-man-gets-pushed-back-200000-years/

- http://www.archaeologydaily.com/news/200908121889/Evidence-for-Use-of-Fire-Found-at-Peking-Man-Site.html

- http://www.unesco.org/ext/field/beijing/whc/pkm-site.htm

- http://www.newstrackindia.com/newsdetails/116718

- http://www.uiowa.edu/bioanth/courses/Peking1.htm

- http://www.archaeologydaily.com/news/201104306509/Did-Peking-Man-wield-a-spear.htmlhttp://www.unreportedheritagenews.com/2011/04/did-peking-man-wield-spear-newresearch.html

- http://www.archaeologydaily.com/news/200912032771/Mystery-Still-Shrouds-Peking-Man-80-Years-after-Discovery.html