© 2018 Halbert Katzen, JD

By Halbert Katzen J.D.

¶ Summary

The Urantia Book, which was first published in 1955, states “From the year A.D. 1934 back to the birth of the first two human beings is just 993,419 years.” [1] It recounts that these first two human beings (Homo erectus) were a set of twins, a male and a female and that they were distinctly different, genetically superior mutations in comparison to their pre-human parents. According to The Urantia Book, they chose to separate themselves from their pre-human clan and that “On their northward journey they discovered an exposed flint deposit . . . Andon [the male] discovered their sparking quality and conceived the idea of building fire. . . The Primates ancestors of Andon had often replenished fire which had been kindled by lightning, but never before had the creatures of earth possessed a method of starting fire at will.” [2] These two ancestors of all mankind are said to have achieved this ability.

A 2004 discovery at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov archaeological site in Israel provides strong evidence that human beings were able to use flint to create fire about 790,000 years ago. Prior to this discovery, the Terra Amata archaeological site in France, though very controversial, provided what was widely considered to be the best evidence for the early ability of human beings to create fire, suggesting that fire was being created sometime between 230,000 and 380,000 years ago. But undisputed evidence for the ability to create fire at will only goes back about 200,000 years. The evidence found at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, with its clusters of burnt flint at different levels, is considerably more definitive than what was found at Terra Amata. This 2004 discovery not only is consistent with The Urantia Book’s assertion that flint was initially used to make fire, but also was found in the general area where the first human beings are said to have lived and, by any analysis, pushes the date closer to what was given in The Urantia Book by hundreds of thousands of years.

¶ Overview

The Urantia Book, published in 1955, states that the first two human beings (Homo erectus) learned how to make fire with flint approximately 995,000 years ago and that they lived in the general area of Mesopotamia.

Excavations at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov archaeological site in Israel, which date from 690,000 to 790,000 years ago, provide strong evidence to support the conclusion that people were using flint to create fire during this time period. A research report from this site was published in 2004.

Prior to the discovery made at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, several sites in Europe and China provided some evidence to support the conclusion that human beings could create fire approximately 400,000 to 550,000 years ago. However, the evidence from these archaeological sites was controversial with regard to whether fire was actually being created or only controlled.

Even when an ancient hearth or other ancient burnt artifacts are found, inherent difficulties are involved with using burnt artifacts to establish the ability to create fire because of the difficulty in determining whether the fire was originally created by humans or was of natural origin and then replenished.

Definitive evidence for the creation of fire dated back about 200,000 years.

Before the 2004 discovery at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, a couple sites in France, Terra Amata and Meniz-Dregan, and the site at Zhoukoudian near Beijing, China were widely accepted as containing some of the best evidence for the early ability of primitive human beings to create fire. The Terra Amata site dates back to 380,000 years ago and the Menez-Dregan site is about 465,000 years old. The site in China is approximately 550,000 years old.

The discoveries made at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov provide evidence for the creation of fire that is missing from the sites in France and China. Specifically, the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site has clusters of flint that are both charred and uncharred.

A 2004 BBC News article by Paul Rincon states:

Researchers from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Bar-Ilan University in Ramat-Gan excavated a waterlogged site at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov.

In 34m-thick ground deposits, they found numerous flint implements belonging to the so-called Acheulean tradition of tool manufacture. Some of these were burnt, while other[s] were not.

The team mapped the distribution of the burnt and unburned artifacts and compared them. Although there was some overlap with the unburned artifacts, the burnt ones clustered together at specific spots at the site.

The researchers think the clusters of burnt artifacts, which date to between 690,000 and 790,000 years ago, indicate the sites of ancient campfires, or hearths, made by either Homo erectus or Homo ergaster.

. . .

Professor John Gowlett, of the University of Liverpool, UK, said that the find was very significant".[3]

The evidence at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site is distinctly more definitive about the ability to create fire than the sites in France and China. The presence of burnt flint at various levels of the site in Israel is altogether consistent with the information presented in The Urantia Book regarding when, where, and how human beings were first able to create fire. The site in Israel is located in the general area where The Urantia Book indicates the first tribes of human beings lived.

When The Urantia Book was published, the notion that human beings were able to create fire 790,000 years ago was not supported by the scholarship of that time period. By any analysis, this site pushes back the ability to create fire by hundreds of thousands of years and, based on a conservative analysis, by approximately 600,000 years.

¶ Complete report

Prior to the 2004 excavations at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov archaeological site in Israel, evidence existed supporting the ability of human beings to create fire that dated back approximately 300,000 to 500,000 years ago. The archaeological sites from this time period were controversial regarding the issue of whether fire was actually being created or only controlled. Definitive evidence for the creation of fire dates back about 200,000 years. The Urantia Book, published in 1955, asserts that nearly one million years ago human beings (Homo erectus) were able to create fire by using flint and that this occurred in the region of Mesopotamia.

Asserting that the first two human beings, Andon and Fonta, conceived of and successfully discovered ways of making fire, The Urantia Book provides the following account of this remarkable achievement:

From the year A.D. 1934 back to the birth of the first two human beings is just 993,419 years.[4]

While still living with his parents, Andon had fastened a sharp piece of flint on the end of a club, using animal tendons for this purpose, and on no less than a dozen occasions he made good use of such a weapon in saving both his own life and that of his equally adventurous and inquisitive sister, who unfailingly accompanied him on all of his tours of exploration.[5]

When about nine years of age, they [Andon and Fonta] journeyed off down the river one bright day and held a momentous conference. . . On this eventful day they arrived at an understanding to live with and for each other, and this was the first of a series of such agreements which finally culminated in the decision to flee from their inferior animal associates and to journey northward, little knowing that they were thus to found the human race.[6]

They had already prepared a crude treetop retreat some half-day’s journey to the north. This was their secret and safe hiding place for the first day away from the home forests. Notwithstanding that the twins shared the Primates’ deathly fear of being on the ground at nighttime, they sallied forth shortly before nightfall on their northern trek. While it required unusual courage for them to undertake this night journey, even with a full moon, they correctly concluded that they were less likely to be missed and pursued by their tribesmen and relatives. And they safely made their previously prepared rendezvous shortly after midnight.

On their northward journey they discovered an exposed flint deposit and, finding many stones suitably shaped for various uses, gathered up a supply for the future. In attempting to chip these flints so that they would be better adapted for certain purposes, Andon discovered their sparking quality and conceived the idea of building fire. But the notion did not take firm hold of him at the time as the climate was still salubrious and there was little need of fire.

But the autumn sun was getting lower in the sky, and as they journeyed northward, the nights grew cooler and cooler. Already they had been forced to make use of animal skins for warmth. Before they had been away from home one moon, Andon signified to his mate that he thought he could make fire with the flint. They tried for two months to utilize the flint spark for kindling a fire but only met with failure. Each day this couple would strike the flints and endeavor to ignite the wood. Finally, one evening about the time of the setting of the sun, the secret of the technique was unraveled when it occurred to Fonta to climb a near-by tree to secure an abandoned bird’s nest. The nest was dry and highly inflammable and consequently flared right up into a full blaze the moment the spark fell upon it. They were so surprised and startled at their success that they almost lost the fire, but they saved it by the addition of suitable fuel, and then began the first search for firewood by the parents of all mankind.

This was one of the most joyous moments in their short but eventful lives. All night long they sat up watching their fire burn, vaguely realizing that they had made a discovery which would make it possible for them to defy climate and thus forever to be independent of their animal relatives of the southern lands. After three days’ rest and enjoyment of the fire, they journeyed on.

The Primates ancestors of Andon had often replenished fire which had been kindled by lightning, but never before had the creatures of earth possessed a method of starting fire at will. But it was a long time before the twins learned that dry moss and other materials would kindle fire just as well as birds’ nests.[7]

Even when an ancient hearth or other ancient burnt artifacts are found, inherent difficulties are involved with using burnt artifacts to establish the ability to create fire because of the difficulty in determining whether the fire was originally created by humans or was of natural origin and then replenished.

What has been widely accepted as the best evidence for the ability of primitive human beings to create fire, before the 2004 discovery at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, is the evidence at the Terra Amata site in France. Additionally, there is the Menez-Dregan site, also in France. Both of these sites are controversial with regard to man’s ability to create fire. These two sites will be used as examples of how the scholarly community has not yet reached a consensus on the issue of when human beings were first able to actually create fire, not just control it.

In 1996 a Discover Magazine article laid out the issues and evidence related to the site at MenezDregan which was discovered in 1985:

While evidence for early human occupation mounted in Spain, farther to the north, on the windblown coast of western France, there appeared hints of another surprisingly early European arrival: fire. In a gully in southern Brittany, anthropologist JeanLaurent Monnier of the University of Rennes found what he believes is an ancient fire pit, tentatively dated as being nearly 500,000 years old, along with some simple stone tools. Conventionally, the first controlled use of fire is thought to have taken place only some 200,000 years ago.

That more recent date at least makes narrative sense: it credits the invention of fireplaces to Homo sapiens, those technological wizards who also came up with sophisticated weapons and tools. But Monnier’s find raises the possibility that fire was tamed not by clever sapiens but by a predecessor, perhaps one closer to Homo erectus, our conservative ancestor who spent millions of years knocking simple flakes off rocks.

[“]There are many fireplaces since 200,000 years ago,” says Monnier. [“]But earlier fireplaces have been less certain.” The difficulty has been to distinguish a fire pit from a natural fire, and charred areas at older sites such as Zhoukoudian in China and V ´ertessz¨oll¨os in Hungary could have been either.

Monnier’s site, in a cave called Menez-Dregan, seems a safer bet. It has a deep concentration of charcoal and burned bones, he says, indicating repeated use over a long time. But the dates still have to be nailed down. This past year, Monnier’s team used a technique called electron spin resonance to date burned quartz from MenezDregan. The technique relies on the fact that normal radioactivity in the quartz is always knocking electrons out of their normal orbits and allowing some to become trapped within impurities in the crystal. When the quartz is heated, though, the trapped electrons return to their atomic orbits. So by counting the number of trapped electrons that had accumulated, the French researchers could measure how much time had elapsed since the quartz was burned by our early ancestors. The elapsed time they got was some 465,000 years. The team is now trying to confirm this date with other techniques.

But what Monnier would really like to puzzle out [is] the simple tools found at the site. They are cruder than other tools of similar age—they are mainly choppers with irregular cutting edges—leading Monnier to wonder why creatures who may have tamed fire couldn’t refine their industrial methods as well.[8]

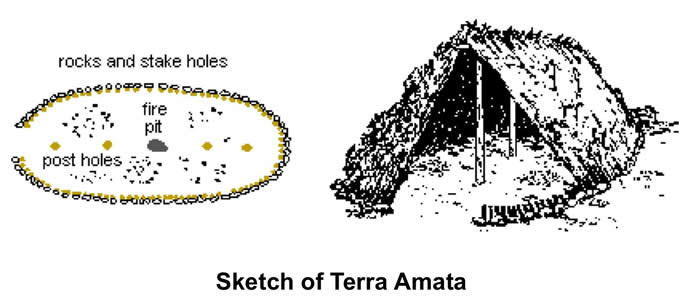

The Terra Amata site in France, excavated in 1966, also controversial within the scientific community, gives a date of 230,000 to 380,000 years ago for the creation of fire. Wikipedia provides this general description of the site itself and the problems associated with drawing conclusions about it:

Terra Amata is an archaeology site near the French town of Nice.

Terra Amata was an open site where you can find Acheulean flint tools dating it to the Lower Paleolithic. It was excavated by a team of archaeologists led by Henri de Lumley, who believed the site contained a series of superimposed living floors and who interpreted arrangements of stones at the site as the foundations of huts or windbreaks. This interpretation would make them some of the earliest examples of human habitation ever found.

However, as with other sites of possible human shelters, such as Grotte du Lazaret, the evidence is more conjectural than compelling. It is equally likely [] that the stones were naturally deposited through stream flow, soil creep or some other natural process. Moreover, Paola Villa has demonstrated that stone artifacts from the different proposed living floors can be fitted together, showing that artifacts have moved up and down through the sediment column. Thus, the supposed living floor assemblages are most likely mixtures of artifacts from different time periods that have come to rest at particular levels. There is, therefore, compelling evidence that the site was subjected to relatively invasive post-depositional processes, which may also be responsible for the stone ‘arrangements’. In [a] building a[t] Terra Amata, a hole was left in the center for smoke to escape. 20-40 people could congregate in a shelter like this.[9]

Kyle Streich, writing for the University of Minnesota website, states:

Some of these shelters contained hearths and what is believed to be some of the earliest controlled use of fire.[10]

In a recent article, Dr. Dennis O’Neil of the Anthropology Department at Palomar College writes:

The earliest convincing evidence of fire use for cooking appears at the 550,000- 300,000 year old late Homo erectus site at Zhoukoudian near Beijing, China and the 400,000 year old presumed archaic human site of Terra Amata near Nice on the French Mediterranean coast. In both cases the evidence is primarily in the form of food refuse bones that were apparently charred during cooking. In addition, there is possible evidence of simple fire hearths at Terra Amata. Unfortunately, there still is not sufficient evidence at either site to say conclusively that there was controlled fire in the sense of being able to create it at will. However, by 100,000 years ago, there is abundant evidence of regular fire use at Neandertal sites. By that time, they evidently were able to create fires when they wished to, and they used them for multiple purposes.[11]

The discoveries made at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov provide evidence for the creation of fire that is missing from the sites that suggest the creation of fire approximately 500,000 years ago. The Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site offers up the presence of flint in clusters that are both charred and uncharred. Regarding this more recently excavated site, a press release from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem states:

The Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site is located along the Dead Sea rift in the Hula Valley of northern Israel.

Dr. Nira Alperson-Afil, a member of Goren-Inbar’s team, said that further, detailed investigation of burned flint at designated areas in all eight levels of civilization found at the site now shows that “concentrations of burned flint items were found in distinct areas, interpreted as representing the remnants of ancient hearths.” This tells us, she said, that once acquired, this fire-making ability was carried on over a period of many generations. Alperson-Afil’s findings are reported in an article published in the most recent edition of Quaternary Science Reviews.

She said that other studies which have reported on the use of fire only verified the presence of burned archaeological materials, but were unable to penetrate further into the question of whether humans were “fire-makers” from the very early stages of fireuse.

“The new data from Gesher Benot Ya’akov is exceptional as it preserved evidence for fire-use throughout a very long occupational sequence. This continual, habitual, use of fire suggests that these early humans were not compelled to collect that fire from natural conflagrations, rather they were able to make fire at will,‘’ Alperson-Afil said.[12]

Note that the “burned flint” is consistent with The Urantia Book’s assertion that creating fire was first achieved by the use of flint, not by igniting wood with heat caused from friction.

A BBC News article by Paul Rincon from 2004 states:

Researchers from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Bar-Ilan University in RamatGan excavated a waterlogged site at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov.

In 34m-thick ground deposits, they found numerous flint implements belonging to the so-called Acheulean tradition of tool manufacture. Some of these were burnt, while other[s] were not.

The team mapped the distribution of the burnt and unburned artifacts and compared them. Although there was some overlap with the unburned artifacts, the burnt ones clustered together at specific spots at the site.

The researchers think the clusters of burnt artifacts, which date to between 790,000 and 690,000 years ago, indicate the sites of ancient campfires, or hearths, made by either Homo erectus or Homo ergaster.[13]

What shows up as a challenging idea to contemporary scholars, is consistent with The Urantia Book’s depiction of Andon and Fonta as the first human beings, who learned how to create fire and to pass this knowledge on to future generations. The site in Israel is located in the general area where The Urantia Book indicates the first tribes of human beings lived. However, it does not state this specifically. In order to get this understanding one must look at statements in The Urantia Book pertaining to the animals from which human beings evolved and from information about the first great spiritual teacher of humanity, Onagar, who is said to have lived about 10,000 years after Andon and Fonta. Regarding the location of the immediate pre-human animals from which human beings evolved, it states:

When about fourteen years of age, they [also a male and female pair of twins] fled from the tribe, going west to raise their family and establish the new species of Primates. And these new creatures are very properly denominated Primates since they were the direct and immediate animal ancestors of the human family itself.

Thus it was that the Primates came to occupy a region on the west coast of the Mesopotamian peninsula as it then projected into the southern sea, while the less intelligent and closely related tribes lived around the peninsula point and up the eastern shore line.[13:1]

Regarding the region where Onagar lived, The Urantia Book says:

As the Andonic dispersion extended, the cultural and spiritual status of the clans retrogressed for nearly ten thousand years until the days of Onagar, who assumed the leadership of these tribes, brought peace among them, and for the first time, led all of them in the worship of the “Breath Giver to men and animals.”

Andon’s philosophy had been most confused; he had barely escaped becoming a fire worshiper because of the great comfort derived from his accidental discovery of fire. Reason, however, directed him from his own discovery to the sun as a superior and more awe-inspiring source of heat and light, but it was too remote, and so he failed to become a sun worshiper.

. . .

That food was the all-important thing in the lives of these primitive human beings is shown by the prayer taught these simple folks by Onagar, their great teacher. And this prayer was:

“O Breath of Life, give us this day our daily food, deliver us from the curse of the ice, save us from our forest enemies, and with mercy receive us into the Great Beyond.”

Onagar maintained headquarters on the northern shores of the ancient Mediterranean in the region of the present Caspian Sea at a settlement called Oban, the tarrying place on the westward turning of the travel trail leading up northward from the Mesopotamian southland. From Oban he sent out teachers to the remote settlements to spread his new doctrines of one Deity and his concept of the hereafter, which he called the Great Beyond. These emissaries of Onagar were the world’s first missionaries; they were also the first human beings to cook meat, the first regularly to use fire in the preparation of food. They cooked flesh on the ends of sticks and also on hot stones; later on they roasted large pieces in the fire, but their descendants almost entirely reverted to the use of raw flesh.[14]

These selections indicate that the presence of burnt flint at various levels of the site in Israel are altogether consistent with the information presented in The Urantia Book regarding when, where, and how human beings were first able to create fire. And the evidence at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site is distinctly more definitive about this ability than the sites in France and China. In drawing conclusions about the discoveries at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site, the BBC article states:

Professor John Gowlett, of the University of Liverpool, UK, said that the find was “very significant”.

. . .

There is always the possibility the fires could have been natural. But the authors say a number of lines of evidence make this unlikely.[3:1]

A review of the research related to the ability to create fire indicates that undisputed evidence only dates this back to about 200,000 years ago. The Menez-Dregan site in France, discovered thirty years after the 1955 publication of The Urantia Book, suggests that this may have occurred 465,000 years ago, but this site as well as others from this general time period do not provide clear evidence for the creation of fire. When The Urantia Book was published, the notion that human beings were able to create fire about 990,000 years ago was completely inconsistent with the scholarship of that time period. The evidence that does hint at the ability to create fire 500,000 years ago was not found in the area where The Urantia Book says this first occurred.

The discoveries made at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov in Israel during this millennium provide evidence for the creation of fire with flint about 790,000 years ago, which is consistent with The Urantia Book’s assertion that the creation of fire began by this means and in this general area approximately 990,000 years ago. By any analysis, this site pushes back the ability to create fire by hundreds of thousands of years and, based on a conservative analysis, by approximately 600,000 years.

¶ Links

¶ External links

- This report in UBTheNews webpage

- Other reports in UBTheNews webpage

- Topical Studies in UBTheNews webpage

- Paul Rincon, Early human fire skills revealed, BBC News, April, 29 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3670017.stm

- Fire out of Africa: a key to the migration of prehistoric man, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, October, 27 2008, http://www.huji.ac.il/cgi-bin/dovrut/dovrut_search_eng.pl?mesge122510374832688760

- Kyle Streich, Terra Amata, June 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20080618062326/http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/europe/terraamata.html, brief description of the Terra Amata site. [Original link broken].

- Dennis O’Neill, Archaic Human Culture, https://www2.palomar.edu/anthro/homo2/mod_homo_3.htm, general info on primitive culture with some info on flint and Terra Amata.

- Wikipedia page about Terra Amata: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_Amata

- Terra Amata museum website, in Nice: http://www.nice.fr/en/culture/musees-et-galeries/presentation-du-musee-terra-amata

- Jennifer Viegas, World’s oldest BBQ burnt meat to a crisp, ABC Science, May, 3 2004, \myurl{http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2004/05/03/1100057.htm?site=science&topic=latest}, article echoing the discovery at the Israeli site.

- When was fire first controlled by human beings? http://www.beyondveg.com/nicholson-w/hb/hb-interview2c.shtml, comprehensive review of the issues,.

- Steven R. James, R. W. Dennell, Allan S. Gilbert, et al., Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence, February 1989, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2743299?seq=1

- Joshua Fischman, A Fireplace in France, Discover Magazine, January, 1 1996. http://discovermagazine.com/1996/jan/afireplaceinfran673, excellent coverage of the Menez-Dregan evidence.

- Wikipedia page about Menez-Dregan: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menez-Dregan

- George W. Rohrer, The First Settlers in France, 1983, http://www.boneandstone.com/articles/rohrer_09.pdf, extensive article on early man in France.

¶ References

Paul Rincon, Early human fire skills revealed, BBC News, April, 29 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3670017.stm ↩︎ ↩︎

Joshua Fischman, A Fireplace in France, Discover Magazine, January, 1 1996. http://discovermagazine.com/1996/jan/afireplaceinfran673 ↩︎

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_Amata_(archaeological_site) ↩︎

Kyle Streich, Terra Amata, june 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20080618062326/http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/europe/terraamata.html [Original link broken] ↩︎

Dennis O’Neill, Archaic Human Culture, https://www2.palomar.edu/anthro/homo2/mod_homo_3.htm ↩︎

Fire out of Africa: a key to the migration of prehistoric man, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, October, 27 2008, http://www.huji.ac.il/cgi-bin/dovrut/dovrut_search_eng.pl?mesge122510374832688760 ↩︎