© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

There were three main Jewish festivals in the calendar of Jesus’ time. They all took place during the dry season, to facilitate pilgrimages to Jerusalem, a place of special longing to celebrate these festivals. At the beginning of spring the religious calendar began with Easter, between March and April. Seven Sundays later the feast of Weeks (Pentecost in Greek) was celebrated, around May. And closing the dry season, between September and October, the feast of Forgiveness and of the Tents. [UB 123:3.5], [UB 134:9.1-3]

This last represented the end of the most significant festivals. Here the official period of rest for the Jews ended, and the return to work began again. now it was time for routine. From that moment on, it was necessary to return to the fields to prepare the land for new crops.

Many authors see in these three ancient festivals reminiscences of festivals related to harvests: the Passover with the early harvests, such as flax; the Weeks with the intermediate harvests,like barley and wheat; and the Pardon and the Stores with the late harvests: the grape harvest and the dates. And it is easy to think this, since it was obligatory for some of these festivals to give certain tithes of the harvests obtained.

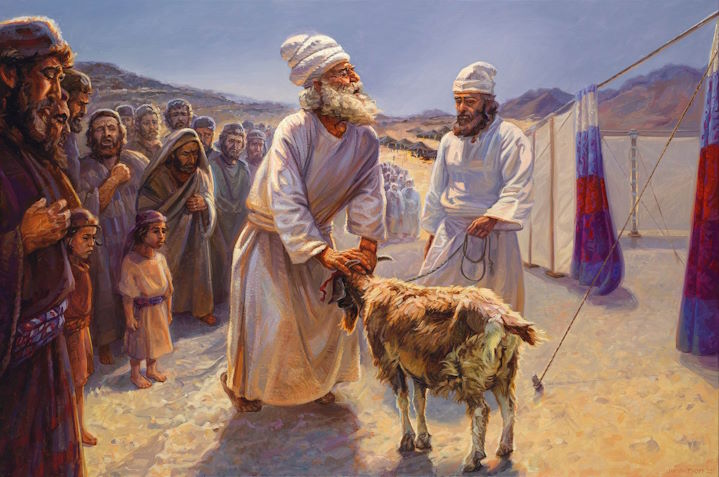

The Day of Atonement, also called the Day of Expiation or Yom Kippur, is a special day in the Jewish calendar. The Sabbath prescriptions were observed on this day to the utmost. Any type of activity was strictly prohibited, except in very rare cases. The day was to be dedicated to fasting, reflection and penitence. Eating, drinking, washing, applying ointments, wearing shoes and making love were prohibited. The high priest himself dressed austerely on this day, with a simple white tunic as a sign of purity and without any ornaments or decorations on his clothing. He also did not wear the usual breastplate, an enormous jewel that hung like a necklace with several precious stones set into it.

The issue of ritual purity, which caused so many headaches for Jesus, was taken to exaggeration on this day. The high priest, to avoid contracting any kind of impurity (it could be contracted through a thousand ridiculous situations) isolated himself seven days beforehand in his house, alone in a room, the high priest’s office. When he left there it was only to attend to the obligatory morning and evening sacrifices, and he did so amidst spectacular security measures.

The information given in The Expected Beginning[1] about an event that occurred that prevented a high priest from officiating the feast is taken from Jerusalem in the time of Jesus (see References). In the chapter dedicated to the high priest, Joachim Jeremiah comments on a passage from the rabbinical treatise Yomá. Apparently, the high priest Simeon ben Kamith, in the time of Jesus (17 - 18 AD), on the eve of the Day of Atonement, at nightfall, received a spit from an Arab sheikh (perhaps because of an argument). The thing is that this made him unclean and he could not officiate the next day, so he had to be replaced in a hurry. This makes me think of these strange cases of substitutions (because there were more): what, a whole bench of high priests on standby? And they all secluded themselves a week before? I suppose so…

However, joking aside, Jesus did not attend the Feast of Forgiveness that year 17-18. Very different occupations kept him away from Jerusalem during that time, when he lived in Damascus. Perhaps one day I will have time to tell it…

What we can clearly appreciate from all this is the extreme obsession that existed in Jesus’ time among his people with this type of prescriptions, which at times were unbearable for the common people. For now, let these brief notes serve as an example of the religious and cultural environment that Jesus lived in.

¶ External links

¶ References

- Johannes Leipoldt and Walter Grundmann, El Mundo del Nuevo Testamento (The World of the New Testament), two volumes, Ediciones Cristiandad, 1973.

- Joachim Jeremías, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1977.

¶ Notes

«The Expected Beginning» is part XI of Jan Herca’s novel [Jesus of Nazareth], a biography of the Master based on The Urantia Book that is in preparation by the author. ↩︎