© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

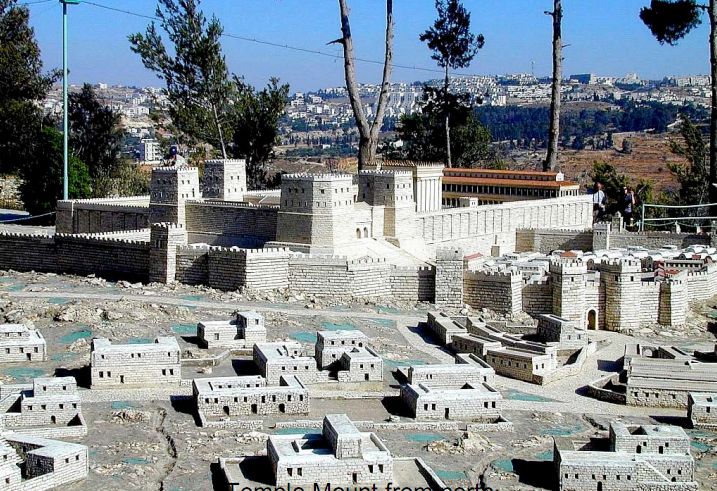

¶ Model of the Holy Land West Hotel in Jerusalem

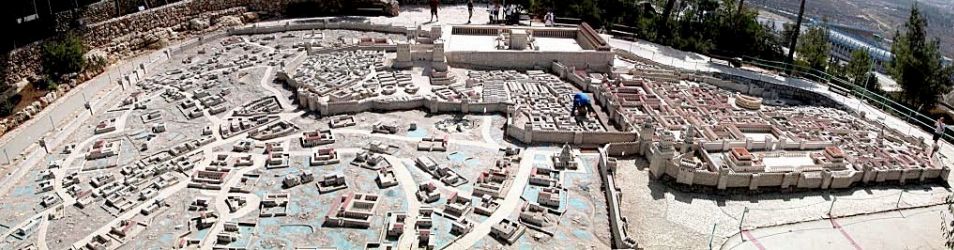

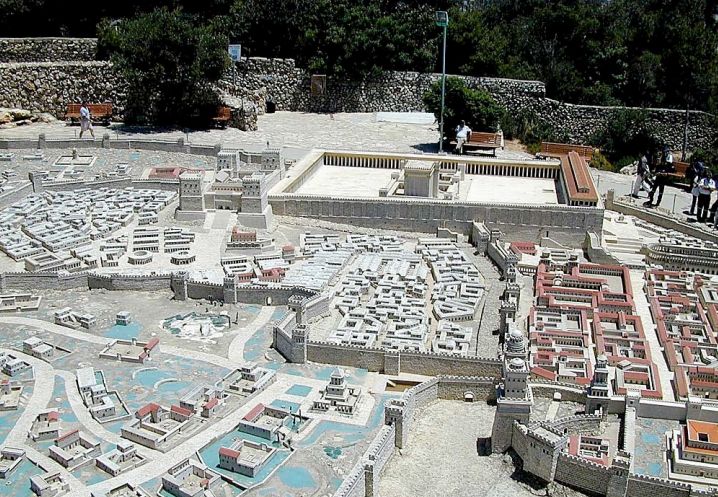

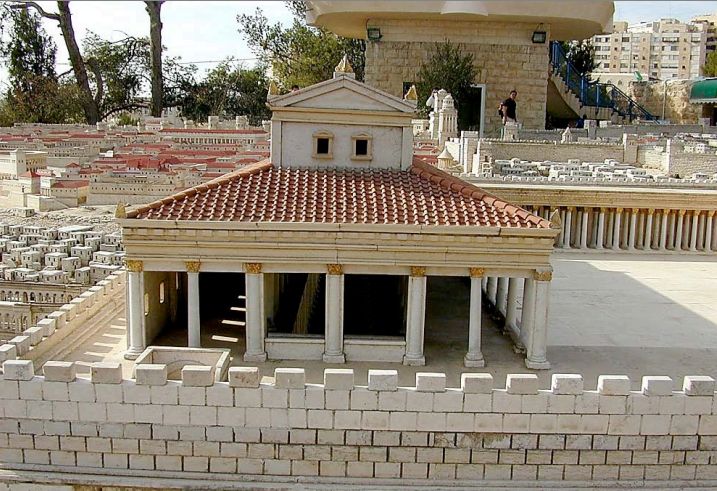

This Holy Land Hotel model is a model of Second Temple Jerusalem. It is 1:50 scale and has an area of 2000 m². It was commissioned in 1966 by Hans Kroch, the owner of the Holy Land Hotel, and designed by Israeli historian and geographer Michael Avi Yonah based on the writings of Josephus and other historical sources. Opened in 1966, it was moved to the Israel Museum in 2006, to a new location.

This map offers an aerial view of Jerusalem in the Second Temple period. The map shows the main features of the model, including the three walls, the Temple and Temple Mount, the Antonia Fortress, the Pools of Bethesda, the hippodrome, the City of David, the theatre, Herod’s palace and the tower. of Psefino. It also includes an inner wall (along the east side of the western hill) which has since been removed from the model.

This model shown here is the largest (1:50 scale) that recreates what it was like Jerusalem in the Herodian era. It does not show exactly what it was like during Jesus’ lifetime, as elements that were only built years later have been added, such as the third northern wall. But it is perfect for getting an idea of what the city was like. at that time. The photographs are by an anonymous author and have been downloaded from the Internet.

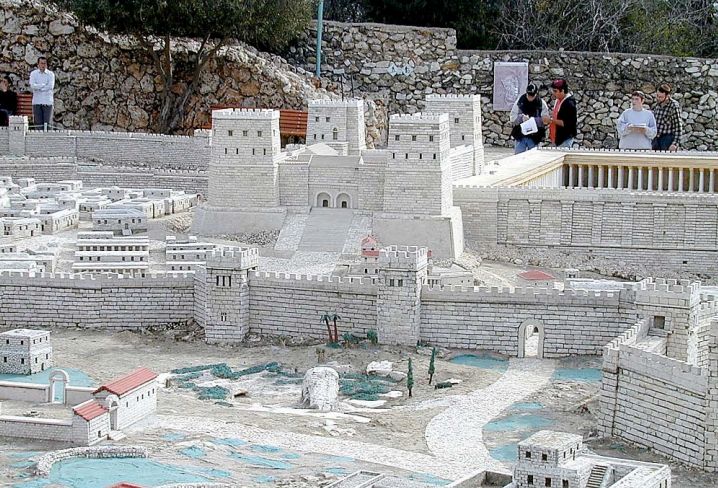

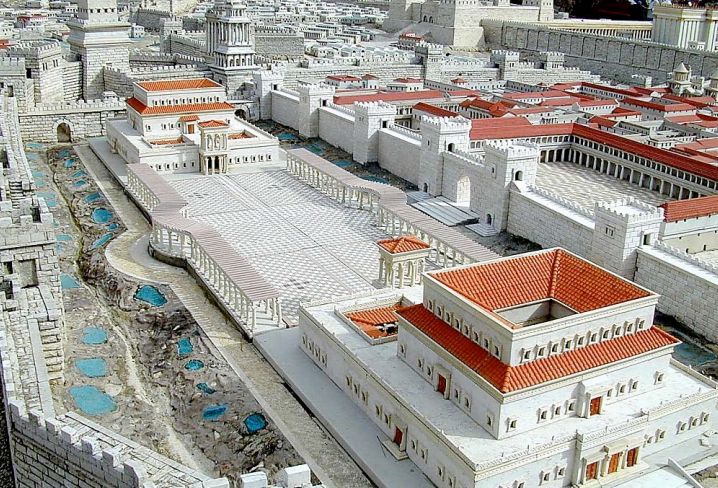

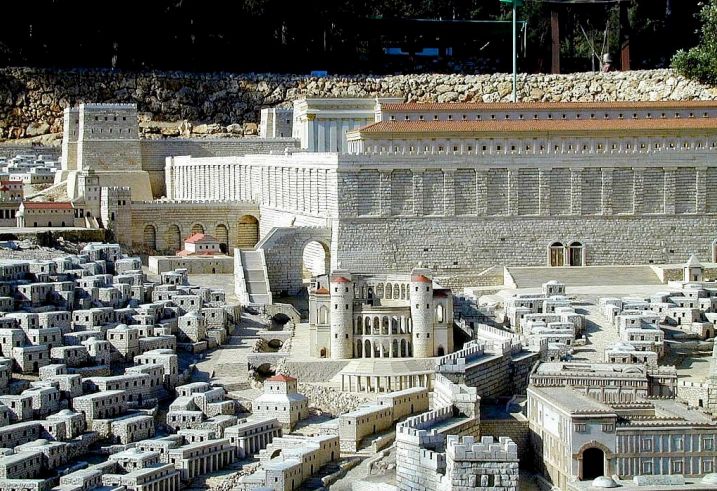

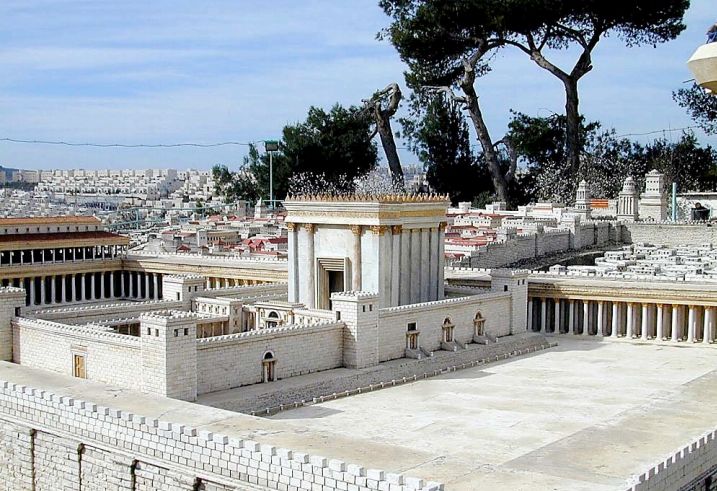

Fig. 2 is a general view of the model, showing Jerusalem from the west looking east. The entire wide area to the right of the photo is the new city, here surrounded by the third northern wall, which did not yet exist in Jesus’ time. The spacious temple esplanade can be clearly seen above in the center.

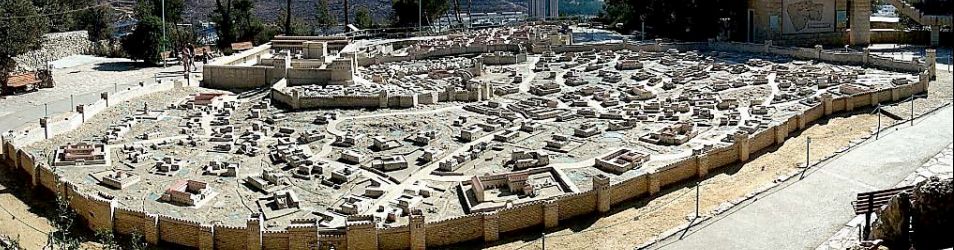

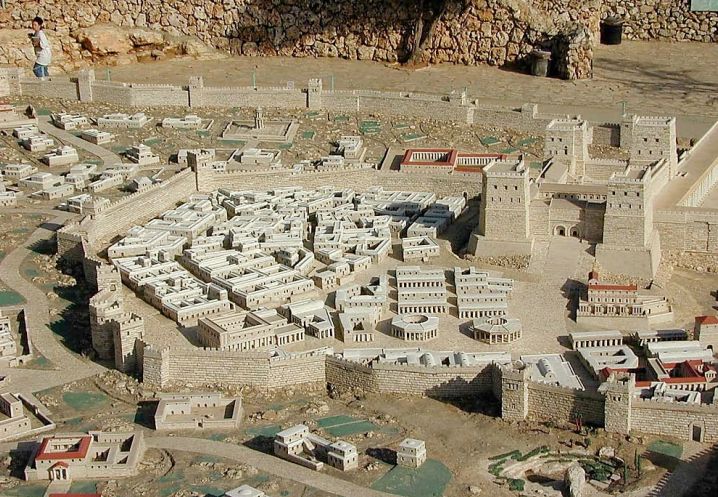

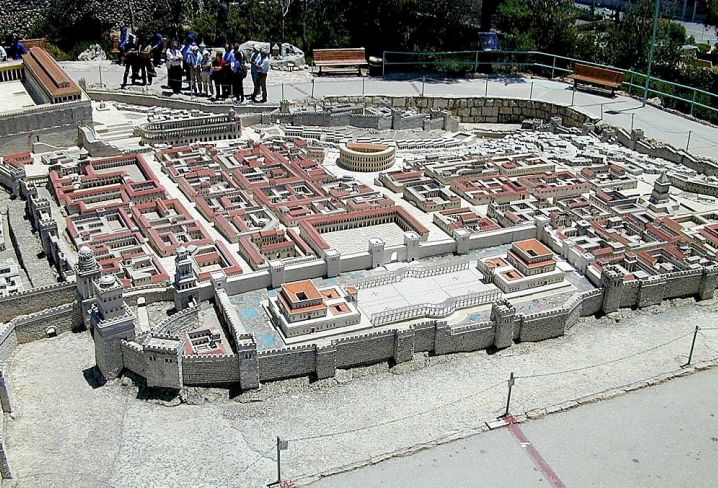

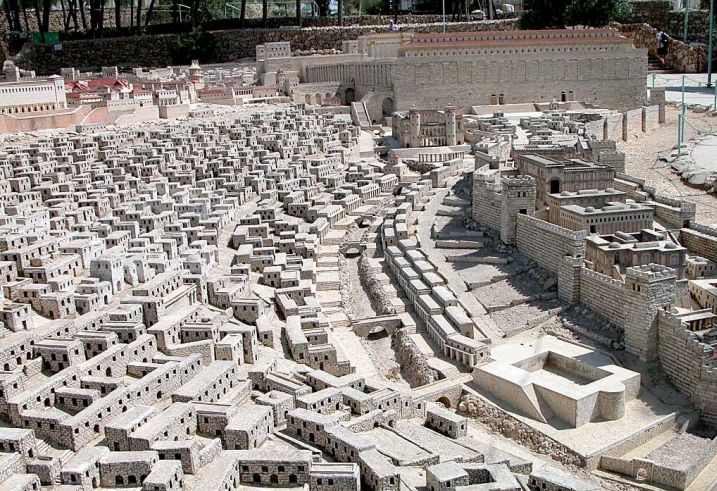

Fig. 3 shows another general view, this time from the north looking south. In the foreground is the third northern wall surrounding the new quarter, which, as we have said, did not exist in Jesus’ time.

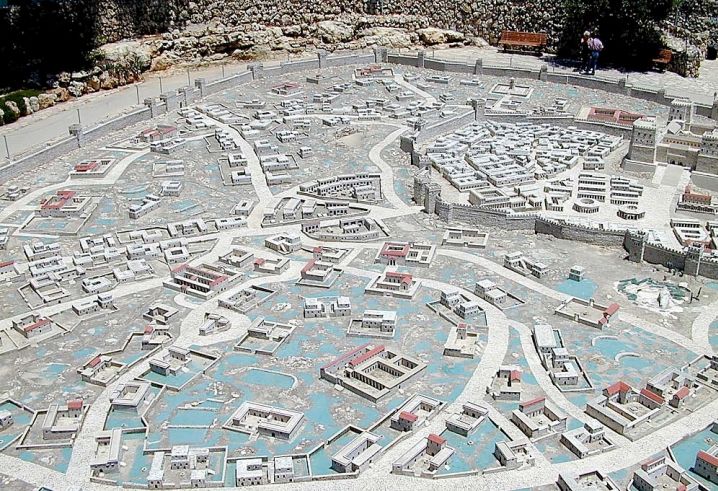

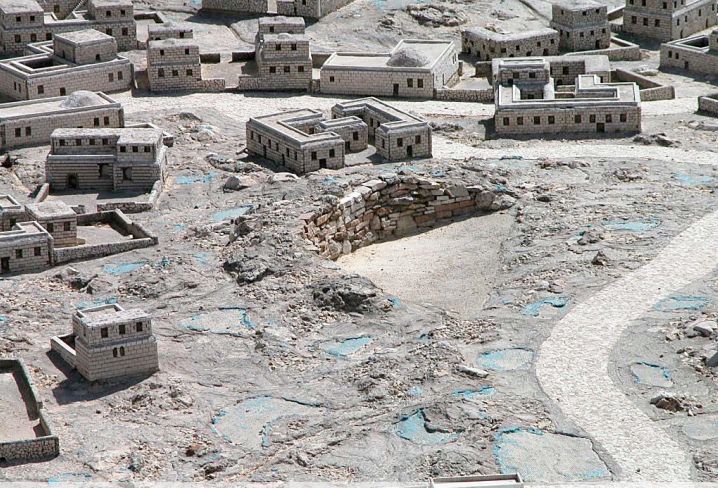

Fig. 4 shows the new city, located to the north of the city, which in the time of Jesus would not have had the wall that we see at the top of the photo. No remains of what the houses in this area were like have been found, so the model places the buildings at the discretion of the artists, although they use typical houses of the period. The blue areas in the photo should be imagined as orchards rather than as pools or ponds, which is what they seem to give the impression of. This whole area was gardens and orchards enclosed by stone walls and crossed by narrow paths. The rich and merchants, many of them pagans, had also established their homes here, as well as a good number of the growing number of inhabitants that the city would have. Therefore, the appearance of the model seems to me somewhat lacking. I would imagine this area to be more of a real orchard full of fruit trees and plantations, as well as areas full of houses crowded together and pressed against each other and the orchards, without leaving a free space. The model usually gives the impression of a lot of space, but the urban pressure must have been more intense at that time.

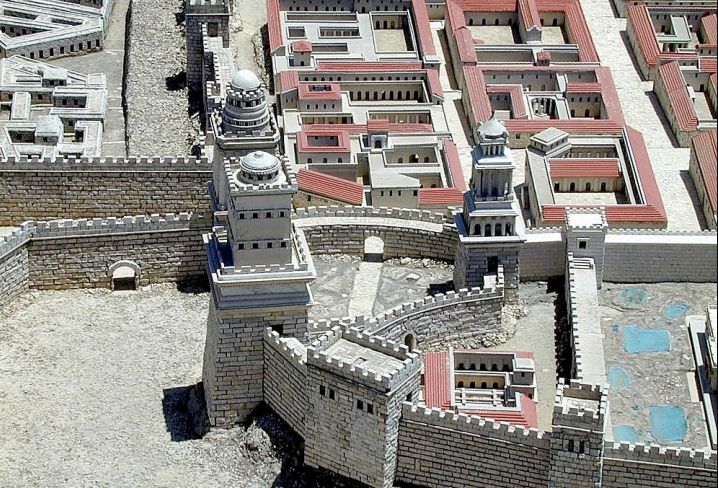

In Fig.5 In the foreground we can see the third northern wall and the so-called Psefino tower, located on this wall. As we have been repeating, all these constructions were built after the time of Jesus.

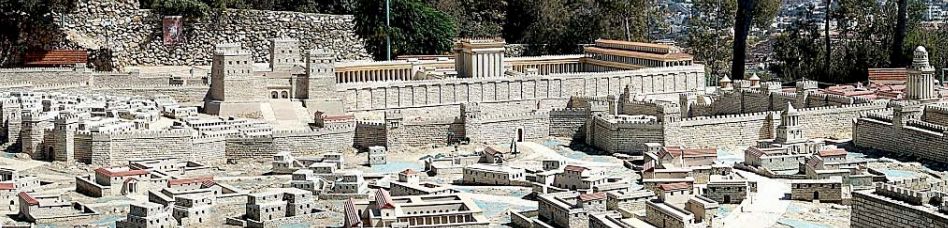

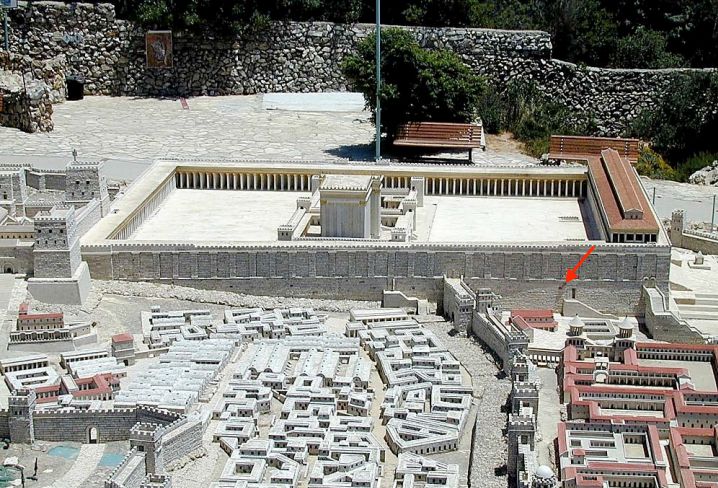

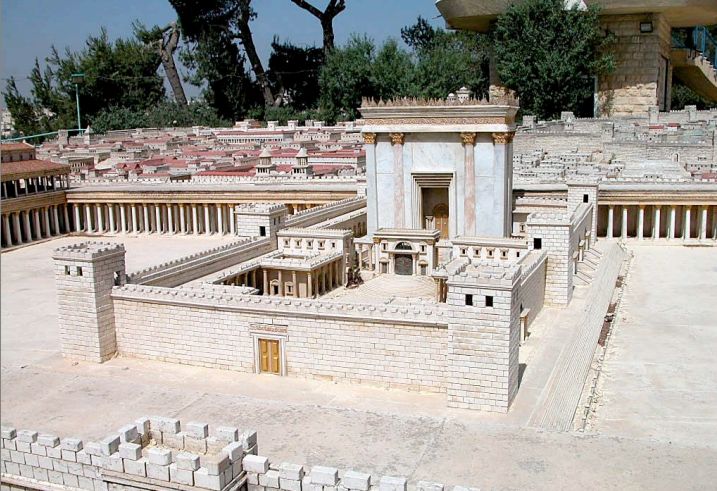

Fig. 6 shows a panoramic view of the Temple Mount. The four towers of the Antonia fortress can be seen on the right, and the temple complex in the center.

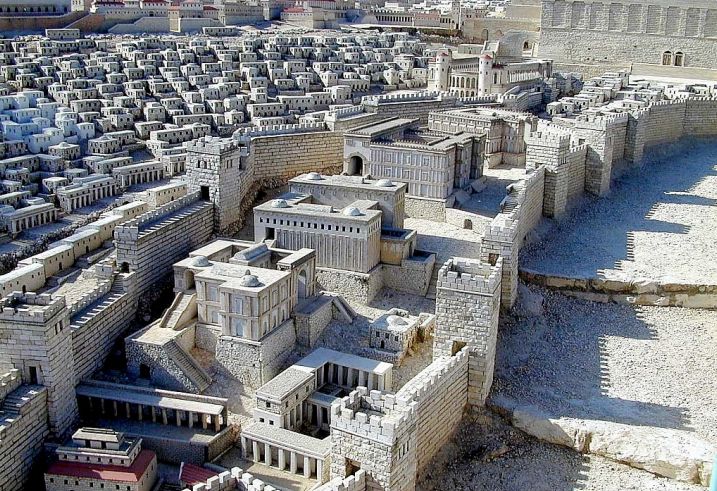

Fig. 7 presents the same panoramic view as the previous figure, but with more perspective. The two northern walls can be clearly seen; the first was actually a viaduct that connected the western façade of the temple with Herod’s palace, and is the wall that runs through the center of the photo from top to bottom. The second, which covers the left area of the photo, surrounded the northern quarter, a relatively new quarter. In the foreground, to the right of the photo, the three towers (Hippica, Phasael, and Mariamme) of Herod’s palace can be seen.

Fig. 8 offers a panoramic view of the second northern wall. Above on the right is the imposing mass of the Antonia fortress, with four towers at its corners. A very high staircase can be seen on the west façade, which personally seems to me to be a somewhat exaggerated entrance. In my description of this building[1] I have chosen to consider an entrance in the north area that ascended to a platform by means of steps and ramps so that horses could climb up without problems. The model lacks the pool called Strution, which should have been located inside the moat. Here the moat only seems to cover the north side, when it should have surrounded the entire castle.

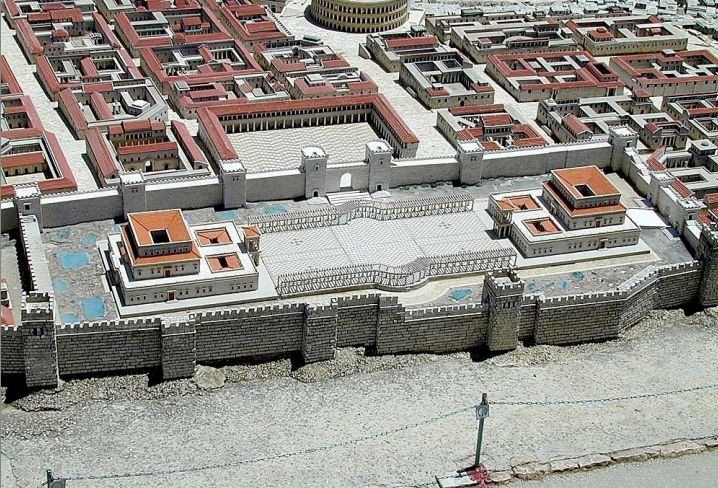

Fig. 9 shows the large temple esplanade with the sanctuary inside, seen from west to east. On the far left is the Antonia fortress. There must have been an access from the fortress to the temple, which cannot be seen in the model.

The red arrow marks the current location of the so-called “Wailing Wall”, the current place of worship for the Jews. As can be seen, the current city is a few metres above the old one. Undoubtedly, if excavated, the rubble and ruins of the existing buildings would be revealed, as has been the case in some archaeological surveys. The complex of small palaces that appears in the lower right corner of the photo with two towers is the palace of the Hasmoneans, the place of residence of Herod Antipas and the rest of the Herodian family during the festivals.

Fig. 10 shows the famous three towers of Herod’s palace, named Hippica, Phasael, and Mariamme. These towers only reinforced one northern end of the huge palace complex, which is out of the picture to the right. The entire palace area and adjacent space occupied Jerusalem’s western hill. This area was known as the Upper City. Many of the city’s wealthy mansions stood here.

According to Josephus, the Roman general Titus destroyed the entire city but chose to leave the three towers intact for the use of his troops. For several centuries these buildings were used as the headquarters of the X Legion. Only one of them survives today and is mistakenly called the “Tower of David.”

The Garden Tomb, shown in Fig. 11, is a present-day site where Jesus’ tomb is believed to have been. However, although this location has some plausibility with the site described in The Urantia Book, being a place located in the new quarter, to the north, where the book tells us that Joseph of Arimathea owned a garden (UB 188:1.2), the reality is that this is where the coincidences end. As can be seen in the model, which reflects the present physiognomy of the tomb[2], the surroundings are not shown correctly, since this should have been a lush plantation full of trees and vegetables, with some bunkers. Therefore, the model has too many buildings and lacks vegetation, stone walls and paths. But even more importantly, the Garden Tomb does not face east but is oriented north-south[3], and it is not placed in the model on the eastern side of a road; instead, the only road provided in the model runs west of the tomb (UB 189:4.6). It is highly unlikely that the famous Garden Tomb was the burial place of Jesus.

Fig. 12 and 13 show the rock of Golgotha, where crucifixions, including that of Jesus, took place. It was located outside the city walls and to the right of the Ephraim Road. As can be seen, the distance separating the Antonia Fortress from Golgotha, the route that the crucified ones had to take when carrying the cross, was not very far. According to The Urantia Book, this location cannot possibly be correct (UB 187:1.4). Golgotha should be outside the city walls, yes, but much further north, for we are told that they left through the Damascus Gate and traveled a stretch of the northern road to reach Golgotha. The present Damascus Gate should not confuse the reader, for it is located in the third northern wall, which was built long after Jesus. It is clear that the present chapel of the Holy Sepulchre has nothing to do with the site of Jesus’ crucifixion, but rather with the replacement of an ancient temple to Aphrodite with a Christian temple.

Fig. 14 shows the “upper city” and Herod’s palace. From here you can also see the hippodrome at the top and the theater. The buildings and streets seem a little exaggerated in size for a city that was to accommodate a large crowd of pilgrims, but some remains found beneath this area of the present city support this recreation. The upper quarter is where the houses of the rich priests were located, such as the house of Caiaphas, where Jesus was tried by an irregular Sanhedrin.

In fig. 15 we have a close-up of Herod’s palace. The upper square must have been one of the many bazaars in the city.

Fig. 16 gives another view of the palace. It had two main wings, each with its banqueting halls, baths, and apartments to comfortably accommodate hundreds of guests. It was surrounded by lush groves, not seen in the model, and pools with bronze fountains.

Fig. 17 allows a detailed view of the central colonnade of the palace, which must also have had fountains and gardens for the enjoyment of the king’s guests, and the adjacent bazaar or market.

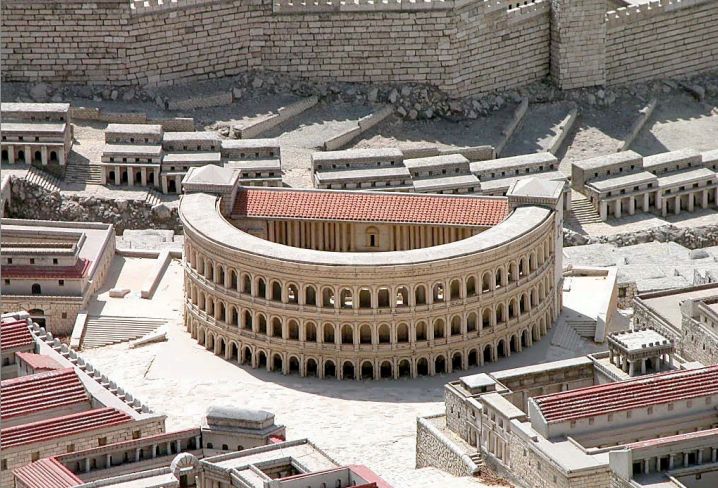

Fig. 18 shows a possible recreation of Herod’s theatre. Its location and appearance are entirely hypothetical, as not a single remnant has been found, although it is known that it existed in the time of Jesus, and even that an amphitheatre existed, but outside the walls. An odeon has recently been discovered under the Wailing Wall, but it is from a later period and it does not seem logical to identify it with the majestic theatre that Herod apparently had built.

Fig. 19 shows the Hasmonean Palace, the residence of Herod Antipas and the rest of the Herodian family during festivals. No convincing remains of this building have been found, and its location is debated. In my opinion, the model places it too close to the temple, and therefore too far down in the city. According to Josephus, Agrippa had an addition or balcony built over this palace, which was said to provide a view of the temple and the Court of the Gentiles. To reach such a height, it seems to me that it should have been located higher up in the city, closer to Herod’s palace.

The image also provides a good view of the southwestern end of the temple, what is now known as the “Wailing Wall” (red arrow). The small, simple building is the “Hall of Hewn Stones,” the usual meeting place of the Sanhedrin. Next to it stands the majestic staircase that leads up to the temple esplanade (known today as “Robinson’s Arch,” after its discoverer). However, the layout of the Sanhedrin chamber is not very precise. It is known that part of it was inside the temple and part outside, that is, as an addition to the temple, and that it was attached to the wall.

Fig. 20 offers a good detail of a typical house in the wealthy quarter. It has a very realistic appearance, with two floors, very narrow alleys, an interior courtyard, balconies, and built with very solid materials, imitating the temple. Remains of these houses have been found in archaeological excavations, such as a house called the “Burned House”, which can be visited by tourists.One would almost expect to see Ben-Hur walking around in that house, which looks very similar to the one he has in Jerusalem in the famous film.

Figs. 21 and 22 show a recreation of David’s Tomb, a monument that existed in Jesus’ time commemorating the burial place of the legendary king, but whose exact location is unknown.

The lower city, shown in Fig. 23, was the poor quarter of the city, crowded together with the simple one- and two-story houses of the common people. The model shows a river of sorts in the center, flowing through what was known as the Tyropeon Valley. Perhaps this is a bit of an exaggeration, but what must have existed is a large underground pipe or channel that drained the rainfall, taking it southwards to the well-known Pool of Siloam, which appears in the model at the bottom right. The pool appears in the model to be a tall building. I would be inclined to think that the building is further south and the pool is dug into the ground, rather than elevated.

Fig. 24 and 25 provide a good close-up of the so-called Mount Ophel, in the area known as the City of David. The model shows this area surrounded by a second inner wall, and closed off from the rest of the city, with several palaces inside, the palaces of the Adiabene royalty. However, I think this is a bit of an inaccurate approximation. These palaces were started right during the time of Jesus or shortly after his death (Queen Helena of Adiabene, who was buried in Jerusalem, died around 50 AD). So I doubt that the palaces of these foreign princes took up so much space in the city. Their palaces were probably modest villas located within the poor part of the city. In fact, Queen Helena is said to have been a great benefactor of the needy in the city, helping them during the years of scarcity. And the inner wall, I rule out that it really existed.

In Fig. 25, to the south, you can also see the so-called Freedmen synagogue and its adjacent hostel.

The preceding figure shows in detail the Pool of Siloam, where a blind man received his sight through Jesus (UB 164:3.8). I have already said that I find its appearance somewhat strange, and I pictured it as a non-elevated pool, situated more at street level, collecting water from a channel through which the rainwater of the Tyropeon flowed. It is very strange that the blind man should be sent by Jesus to an elevated pool. How could he be expected to climb the stairs by himself?

Fig. 27 shows a close-up of the hippodrome. Its location is unknown and it is customary to place it south of the temple, but it is strange to think that a place of such little interest to the Jews was so close to the temple. In fact, archaeological excavations have not found any remains of a hippodrome in this area, but they have found the remains of a colonnaded street through which the model shows a canal running, which we have already said must have been underground.

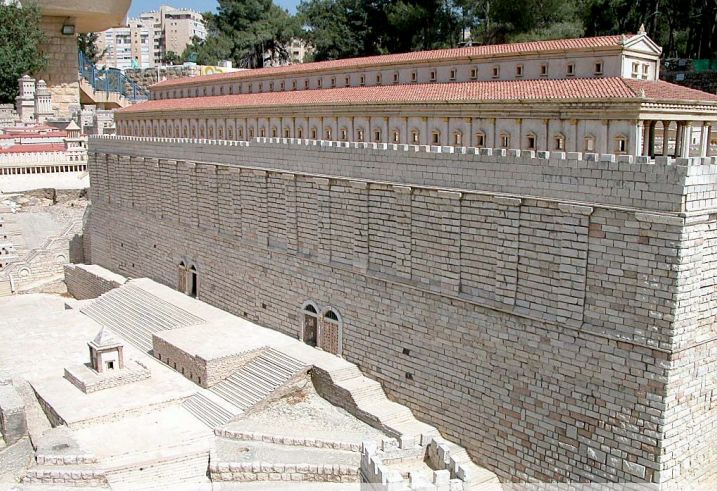

Fig. 28 allows us to appreciate the colossus of the Temple, at the top of the mount, looking at it from the south. You can see the staircase that, ascending over a huge arch (called today the “Robinson’s Arch”), allowed access to the royal portico. Behind this staircase, in the centre of the photo, you can see the building called “the carved stones”, which must have served as a meeting place for the Sanhedrin. On the large south façade of the temple you can see two access doors (the so-called “Double Door”) that seem tiny but were two profusely decorated monumental entrances. The doors are not at the height of the temple esplanade and what was behind them was a large staircase that allowed access to the temple, just as through the arch.

Fig. 29 shows a close-up of the staircase and arch (“Robinson’s Arch”) that provided access to the Portico Regio through the doorway of the Basilica. Behind, the building of the “hewn stones”, at the foot of the viaduct that led to the gate that I call “Royal” because it led to Herod’s palace (and allowed the king and the wealthy people of the “Upper City” to access the temple without mixing with the common people, who normally entered through the other, more crowded gates). You can appreciate the immensity of the temple walls, 50 meters high, a current building of about 15 floors.

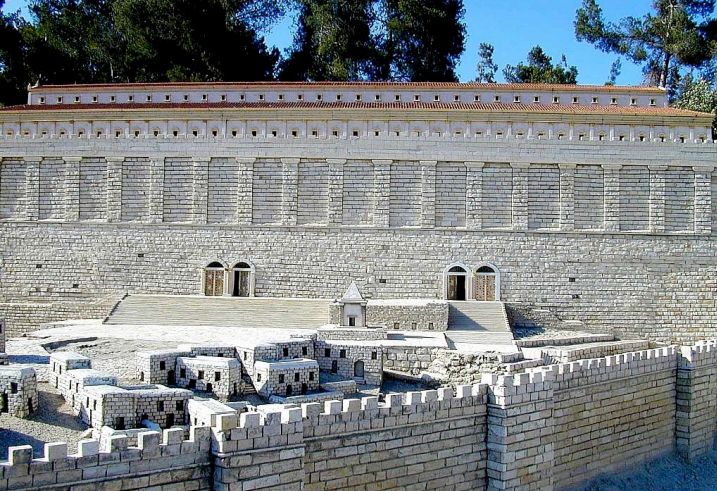

Fig. 30 shows the south wall of the Temple, with the Hulda Gate, the Double Gate, and the Triple Gate. The number of openings in these doors is disputed. Here the model has two openings in both doors. Others want to see three openings in the Triple Gate. Also visible on the steps leading up to the Temple is the building with the public baths or miqwaoth, and in front of it the monument to the prophetess Hulda. Fig. 31 shows another view of the south wall of the Temple, in which all these elements can be better appreciated, as well as the magnificence of the Royal Portico.

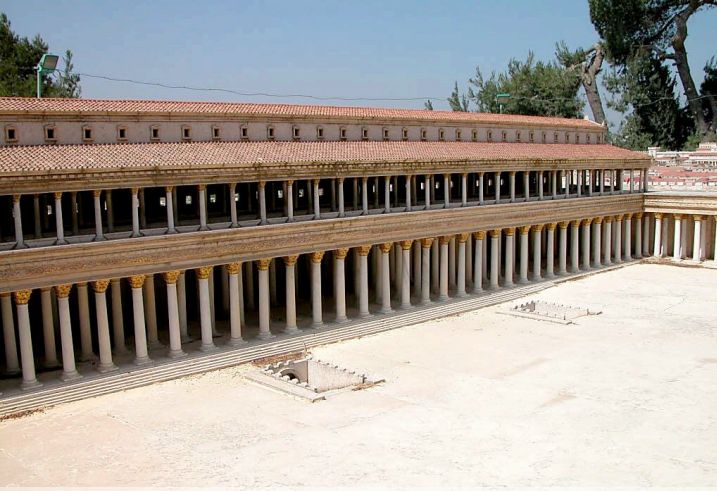

Fig. 32 offers a good panoramic view of the Portico Regius, or Royal Basilica, with the Royal Stoa above it. Two staircases, the underground entrances leading from the Hulda Gate, can be seen on the forecourt called the Court of the Gentiles.

The famous Temple moneychangers served in this basilica, and trials were also held there. Some of the columns of the portico have survived to this day.

Fig. 33 shows the Royal Stoa, above the Basilica or Portico Regius, viewed from the west. The Sanhedrin moved here from the “chamber of hewn stones” shortly after Jesus’ death. It is worth noting that at the time of Jesus some parts of the Temple, such as this Stoa, were still under construction.

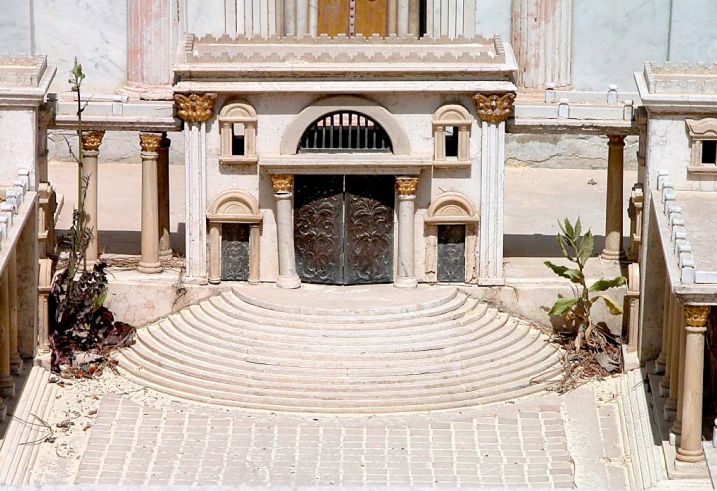

Fig. 34 shows the sanctuary enclosure of the Temple, surrounded first by a fence or soreg (with warning messages for non-Jews not to cross it), and then by a wall with towers and adjacent chambers for priestly offices. The semicircular steps lead to the gate called Nicanor’s Gate, made of shining bronze. Some believe that this gate is the same one that Acts 3:2 calls “Beautiful Gate”, , but according to the description in The Urantia Book (UB 162:4.3) the “Beautiful Gate” would correspond to the eastern gate of the sacred precinct.

The courtyard in the foreground is the women’s courtyard, where women were allowed access. The second courtyard, where the Sanctuary stood, was the priests’ courtyard, where only men were allowed access. The Sanctuary, the immense building 60 meters high! that stood out in the middle of the entire city, was only accessible to priests and only for certain rituals. The immense entrance gate was covered by a large veil (not in the model) that hung on the outside. Similar veils were placed inside separating what was called the sanctasanctorum, a place reserved only once a year for the high priest, and where it was believed that God himself was present.

Fig. 35 shows the same enclosure from another angle, with the only eastern door leading into the enclosure (called by The Urantia Book the “Beautiful Gate”), and Fig. 36 offers a larger panoramic view of the complex, in which the low wall for the Gentiles, the access stairs (where Jesus often stood to preach, since from there both Jews and Gentiles could hear him clearly) and finally the doors leading into the sanctuary can be better seen.

In Fig. 38 one can see the atrium and the Portico of the Gentiles, next to the Antonia fortress. It was in this space and in the Portico of the Gentiles that the merchants of sacrificial goods (animals and fruits) probably set up their stalls, which were introduced through the northern gate of the temple, precisely called the “Sheep Gate.” It was here that the famous expulsion of these sellers by Jesus and his disciples took place (UB 173:1.1-11).

Fig. 39 shows the Antonia Fortress from the east. The model has two flaws in my opinion. One is the access by means of very long and steep stairs, which I find very impractical for soldiers and cavalry. Another is that the wall did not surround the castle, making it more vulnerable, and there is also no trace of the moat that undoubtedly surrounded the entire castle.

The same view of the Antonia Fortress, but now from the west, can be seen in fig. 40. I find the formidable dimensions of this model very appropriate, no doubt in keeping with Josephus’ description of the building, which speaks of a city in itself. Inside it one or more courtyards can be seen surrounded by crenellated walls and strong towers at the corners. However, what is missing is what I believe was the main entrance, to the north, which must have been accessed by a drawbridge over the moat.

Fig. 41 offers a good view of the entire Temple Mount seen from the north. The wall in the foreground is the second northern wall. The gate in the wall is most likely the one that The Urantia Book (UB 187:1.4) called the “Damascus Gate” (not the current gate called “Damascus,” which is located in a third wall that dates back to after Jesus), through which Jesus was led to Golgotha.

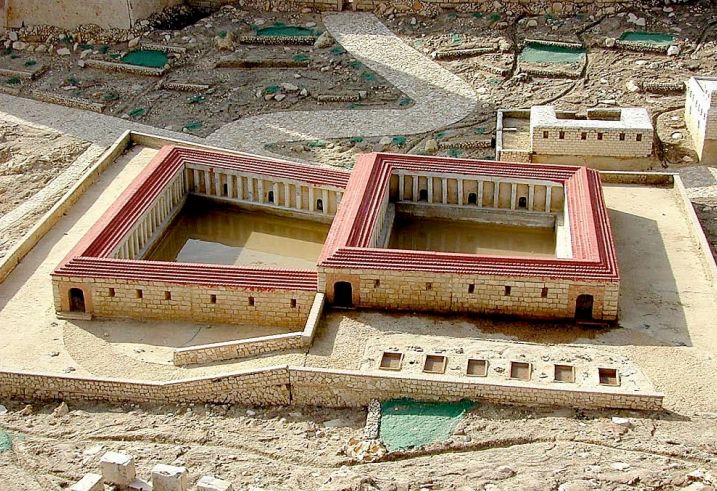

Fig. 42 is the last in this collection of images of the model of the Holy Land Hotel in Jerusalem. It shows in detail the “Pool of Bethesda,” two columned pools located near the Antonia fortress. This is the site of a healing by Jesus (UB 147:3.1).

¶ References

¶ Notes

In the description made in the novel «Jesus of Nazareth», a biography of the Master based on The Urantia Book that is in preparation by the author. ↩︎

360 Panorama in Google Maps of the tomb of the garden. It allows you to clearly see its north-south orientation. ↩︎