© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

We distinguish three social strata: rich, middle class and poor.

¶ The rich

¶ a) The court

The Jewish people in Jesus’ time lived under the auspices of the Herodian family. First under Herod the Great, and later under his sons, there was always a court surrounding the prince or king. This court directed official life; even in the times of Roman domination, the princely courts played their role, although they were only pale reflections of their former magnificence.

Kings and princes often had a good number of wives, such as Herod the Great, who had ten. Along with these wives, they also had a large harem of concubines. The entire family of the king or prince also lived in the palace, and all the monarch’s friends and relatives, however distant, were frequently invited to the palace.

These royal palaces were served by a vast troop of guards, doormen, servants, chamber attendants, ministers, chancellors, bodyguards, company, musicians and much more. This entourage, obviously, did not all live in the same league as the leaders, but they did enjoy an enviable social position.

Along with the sovereign’s court there were also other minor courts, which were located in the palace, and had their own retinue and their own particular service.

The monarchs’ tax revenues were impressive. Only in this way could they meet, and sometimes not even in this way, the enormous expenses of their luxuries and extravagance. Herod Antipas received 200 talents in taxes from his territory annually; Philip, 100; Archelaus, and presumably later the procurators, about 500; and Salome, from her territories, 60. In other words, the entire Jewish territory could contribute some 800 to 1000 talents each year. In the time of Herod the Great, this figure could even have been higher, because the cities of Gaza, Gadara and Hippos also belonged to his kingdom, which later passed into the province of Syria. Take as a comparison that a talent of that time was about €300,000 in 2006.

Despite this income, the monarchs were unable to meet their expenses. Herod also possessed an impressive private fortune, and made great wealth by confiscating the property of many nobles. In addition, in 12 BC the Emperor Augustus gave him the copper mines of Soli in Cyprus, which gave him new income. Finally, gifts, or rather bribes, filled more than one hole in the princes’ finances.

¶ b) The wealthy class

There was an upper aristocratic stratum, which consisted primarily of the priestly nobility and members of the high priest’s family. They derived their income from the temple treasury, from lands they owned, from temple trade, and from nepotism in the appointment of their relatives to the leading positions, which increased the family’s wealth. The high priest had to bear the expenses inherent in his office; for example, he had to pay out of his own pocket for the sacrifice of the Great Day of Atonement. For reasons of representation he was obliged to keep his house open to all. The families of the high priests were extremely luxurious. They generally belonged to the richest families in Palestine.

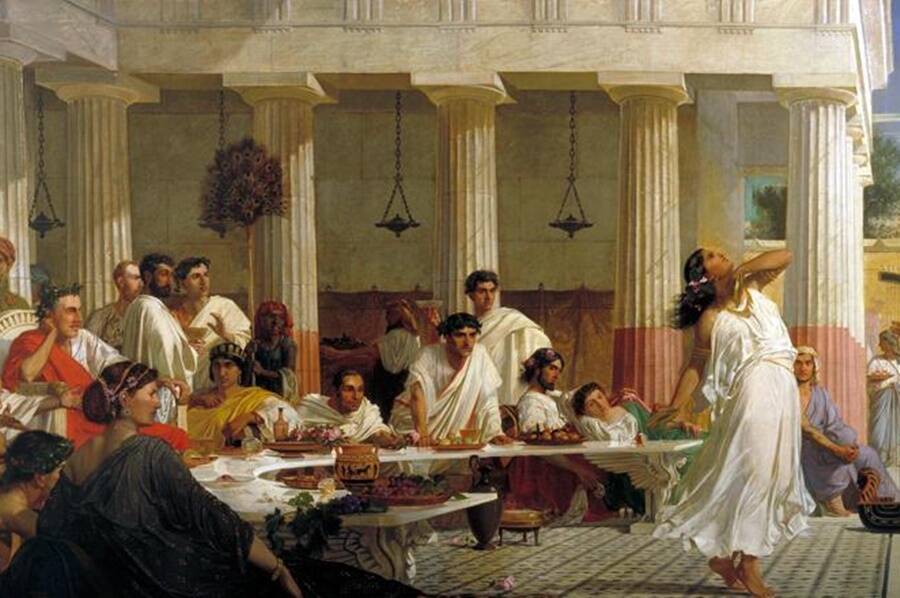

Along with the high priestly circle, the upper stratum of the rich also included the great merchants and large landowners, called eyschemon, who were represented as elders in the high council, the Sanhedrin, and who mostly lived in Jerusalem or nearby, as well as the tax collectors. This was the case with Jesus’ two friends, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. At home they also led a luxurious life, visible in the ostentation of their housing and clothing, in their banquets and jewellery, and in the trousseau of their daughters when they got married. At the magnificent banquets they gave, it was customary to issue a prior invitation with the names of those invited and to send a second definitive invitation on the day of the banquet, which is reflected in Jesus’ parable about the guests invited to the banquet. There were even open banquets to which anyone who wanted to come was invited. Music and dancing accompanied these banquets. These houses were intended to emulate the royal court, which surpassed all others in luxury and pomp.

¶ The middle class

Alongside the large merchant who imported goods from far away and stored them in large warehouses, there was also the small merchant who had his shop in one of the bazaars. Here a distinction must be made between large merchants (emporoi) and small merchants (kapeloi). Furthermore, artisans, insofar as they owned their workshops and did not work as wage earners in someone else’s house, belonged fully to this middle class. There were no factories, and therefore there was no working class. From artisans one passed directly to employees or serfs, and then to slaves.

In everyday life, it was normal practice not to pay wages on a daily basis unless specifically requested; they were usually paid within 24 hours after the work was finished; in the temple, on the other hand, the scriptural prescription was scrupulously observed, which ordered the payment of wages on the day of the work. Certainly, taking great advantage of the temple was regarded as a serious offence.

Frequent travel made lodging a business. Pilgrimages, especially to the holy city, were also a source of work for many middle-class families.

A large number of priests also belonged to the middle class. Most of them lived by practising a craft or trade, apart from the tithes, of which they were entitled to a portion. However, the income from these cannot be overestimated, since, on the one hand, the number of priests was excessively large and, on the other hand, tithes were paid only reluctantly and in many cases were not even paid. When they were paid, they were paid in the form of produce from the fields. In addition, although only during the days of their service in the temple, they received part of the sacrifices and the first fruits offered at the harvest thanksgivings.

¶ The poor

The number of poor people was large. Among them, the most numerous were the day labourers; the average wage of a silver denarius was enough to cover the basic needs of a small family. If he could not find work for several days, the day labourer would be left in absolute poverty.

Slaves and freedmen, especially in the period immediately after their emancipation, had no property or income and were therefore forced to live off outside help. Jewish slaves lived in Jewish households under the protection of the law and were regarded as day labourers who sold their labour for a fixed period; the sabbatical year, which was repeated every seven years, brought them freedom if their master was Jewish. The position of pagan slaves was more serious, and they often tried to improve their situation by converting to Judaism by becoming proselytes. The protection of the sabbatical year did not extend to these. Their masters could inflict corporal punishment on them. They had no rights whatsoever. But in any case the number of slaves in Palestine could not have been very large.

Among the poor there were also many doctors of the law or scribes. The incompatibility between the study of the Torah and the exercise of a profession was very early established. Since the teaching of the law was to be free, the teachers had to live on the aid given to them, which consisted, more or less, of invitations to take part in banquets held in other houses and of the support they received from their administrators and followers. This seems to be shown in the life of Jesus and his disciples, since Jesus was considered a rabbi. The doctors of the law were included in the distribution of the tithe of the poor, to which the amount of the tithes was allocated every three and six years. Their poverty aroused in them a certain greed and induced them to abuse hospitality; for example, that of widows, whose rights they declared they were ready to represent, a fact that Jesus particularly criticized (Mt 23:14, Mk 12:40, Lk 20:47). In contrast, the doctors of the law who were at the service of the temple had regular incomes; however, their number was not large, since there were also doctors of the law among the priests.

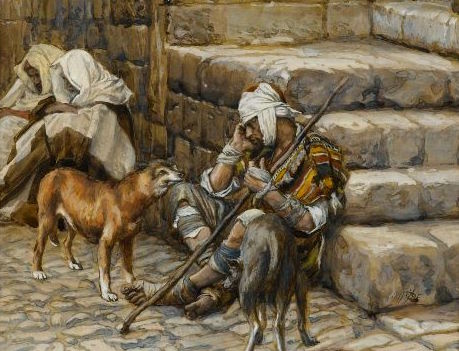

A special role was played by beggars. Most of them were blind, crippled or maimed, who were forced to beg. There was no official social welfare provision. If such individuals did not want to be a burden on their family, they had to beg. In fact, the family often took advantage of their situation, since charity and alms were held in high esteem by the Jews as particularly meritorious deeds. A good beggar’s position at the temple gates, on the pilgrims’ roads or at places of purification, such as at the Pool of Bethesda or at the outlet of the Siloam Canal, could be very profitable. The truly poor beggars were mixed with dissemblers, who pretended to be blind and crippled, lazy people and unsociable people, who exploited charity especially on religious holidays. Jesus detected and denounced this many times, although it is not reflected in the gospels (UB 140:8.13). The truly blind, crippled, and maimed were in a difficult situation not only economically but also religiously. The law forbade them to enter the sanctuary. Those afflicted with leprosy also figure among the group of poor and excluded, who are relegated to living on charity (see article on leprosy in the time of Jesus). Against the background of such provisions, the stories of miracles that refer to Jesus make more sense: with his healing, the sick were given access to the kingdom of God.

Poverty in Jesus’ time was gradually increasing. This was greatly contributed to by the abusive exploitation of the country by kings and governors, as well as the wars and plundering that occurred repeatedly during the turbulent events of this period. All this brought with it famine and famine, as well as the mutilation of many of its inhabitants. But there was no lack of attempts to provide help when great disasters arose. We have evidence of such aid being provided in the time of Herod the Great during the severe famine crisis of 25-24 BC. Private charity was encouraged and was highly esteemed. The aspiration of the poor to share in the harvest was given legal sanction. A corner of the land was left unharvested for them, which they could collect from the fields and vineyards after the harvest. The grapes that fell during the grape harvest belonged to them. Cult communities also made efforts to help the poor or impoverished people. It is also worth remembering here that Jesus, in his preaching, was not indifferent to this reality of his people. Through his teachings we can guess the existence of many people who live in extreme poverty and his concern for social assistance, as in the case of the poor widow who makes an offering to the temple (Mc 12:41-44, Lk 21:1-4, UB 172:4.2).

¶ References

-

Johannes Leipoldt and Walter Grundmann, El Mundo del Nuevo Testamento (The World of the New Testament), two volumes, Ediciones Cristiandad, 1973. Volume I. Historical-cultural study, pages 201 and following.

-

Joachim Jeremiah, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the time of Jesus), Christianity Editions, 1977.

-

Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985.