© 2009 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ Introduction

Leprosy has been a well-known pathology since ancient times, stigmatizing, mutilating, socially marginalizing, chronic, with a most florid and variable expression, terrible for the patient, marking their way of life and their destiny. Its slow evolution made this disease an ordeal, whose ancient therapy was based on combating its symptomatic states, a result of the limited knowledge of the time.

The term “leprosy” comes from the Greek and means “scaly.” The Greek word used by Hippocrates and the physicians of Hellas called leprosy the scaly-appearing lesions that appeared on the skin, what we know today as psoriasis. They also called this type of lesion “psoriasis léuki,” which means white leprosy.

The problem apparently arises from translations of the Bible, on the one hand, and from the Arabic versions of Greek works, on the other. Thus, the Hebrew term “tsara’ath,” which designated whitish skin lesions, is translated by the Greek word “leprosy.” As with many other biblical terms designating diseases, the lack of identification has led to insoluble translation problems. Tsara’ath is the word applied generically to all skin diseases.

Maimonides already interpreted it this way in his “Tumat ha-tsara’ath,” where he identifies this word as dermatitis or dermatosis. Thus a distinction is made between néga ha-tsara´ath (primary syphilis, yaws), tsara´ath or basar (ulcus durum), tsara´ath puráht (secondary syphilis), tsara´ath noshénet (tertiary syphilis, yaws),tsara´ath ha-rosh (trichophycy or tsara´ath of the head), and tsara´ath ha-báyit (saprophytes, dirt, contamination).

Although tsara´ath is usually interpreted as leprosy, only tsara´ath ha-metsah is leonine leprosy. The fact that tsara´ath was cured within days or weeks indicates that it was not always leprosy. (UB 166:2.7)

A distinction is also made in the Biblical texts between tsarúa (luetic or bejel, yaws or pinta) and metsorá (leper). The Greeks were familiar with true leprosy and described it as elephantiasis because of the facial deformity produced by this disease, whose nodules or lepromas, as they grew and coalesced, resembled elephant skin.

Then, when the Arabs began to translate Greek authors, the second confusion arose when the word elephantiasis was interpreted as “Dal-Fil,” which means “elephant’s foot.” From this, different terms have emerged in the history of medicine to designate the true Hansen’s disease: elephantiasis graecorum and elephantiasis arabum.

The Hebrews used the word juzam to describe Greek elephantiasis or modern leprosy, and juzam would be translated into Latin by means of the Greek word lepra, the same word used by the ancient Greeks to designate a series of diverse skin lesions.

Lucretius and Celsus would distinguish between elephantiasis graecorum or the Greek elephantiasis and lepra graecorum, or psoriasis and related diseases. Little by little, the sonorous name “leprosy” replaced the no less sonorous, but longer, elephantiasis graecorum, and today it is legally accepted.

¶ Antiquity of Leprosy

Studying ancient texts from various Eastern cultures, it has been possible to observe and note descriptions of this disease in documents as old as the Brugsch Papyrus (2400 BC).

Meanwhile, the works of Susruta, in India (Susruta Samhita), and Charaka, two of the most famous Hindu physicians (500-100 BC), already mention an infectious disease, one of whose varieties produced the “loss of the sense of touch,” a clear allusion to anesthetic leprosy.

In China, it is mentioned in several Pensions and in the Annals of Confucius (600 BC). The Old Testament (Pentateuch, Leviticus) establishes the concept of lepers.

Considering the age of each documentary evidence, a first impression seems to show that it was known from very early times in Egypt and the East (Mesopotamia and India). Later, it appeared in China and Japan, and in the West in Greece, the Italian Peninsula, and North Africa. By the Middle Ages, however, it had spread throughout Europe. Let’s examine this initial impression in more detail.

The Vedas of India record very ancient ideas and oral traditions dating back to 6,000 BC. The idea of leprosy can already be observed in the Vedas, the idea of the existence of this disease in Asia in very ancient times. Hindu medicine was familiar with true leprosy and its medical treatment with methods that we can describe as “modern,” at a time when it was not yet known in Greece, or at least there is no documentary evidence, since there are no written sources from that age in Europe. In the Atarva-Veda and the Manava Darma Castra, the symptoms of true leprosy are described (1500 - 500 BC), and various prophylactic measures against this disease are recommended. In the Susruta Samhita (600-100 BC), leprosy is mentioned as Vat-Rakta, Vat-Shomita, and Kushta, and chaulmoogra oil is recommended for its cure. In India, the word kushta was known from that ancient time, encompassing a large number of skin diseases, among which Hansen’s disease predominates.

In China, a term, li or lai, existed from very ancient times, which encompassed a wide variety of skin lesions, from psoriasis to prurigo and eczema, and possibly leprosy. Also in Sanskrit, there is the word kilasa, which designates leucoderma. Ancient Chinese texts such as the Shan-Han-Lun and the Kun-Yin-Chen-Sien-Chuan describe a disease in which the body is covered with ulcers with a repugnant appearance and smell. No fewer than 15 Chinese words have been identified to designate skin lesions compatible with leprosy. The most apparently significant are the aforementioned terms li and lieh, lieh-fang and wu-chi, which are still in use today to designate leprosy. In Chinese texts, in addition to descriptions of leprosy, it is treated with purgatives, diaphoretics, and arsenic. One of Confucius’s disciples, named Pe-Nieu, is said to have died of leprosy. The chronicle of the Chu dynasty contains a detailed description of true leprosy. Hua-To, the famous Chinese physician-surgeon who was beheaded by one of the Chinese emperors, who thought he was trying to kill him by recommending cranial trepanation for his cure in 190 BC, gives a detailed description of leprosy and its forms in his work “Complete Secret Remedies.” He details the nodular lesions, hoarseness, anesthesia, and contagiousness of the disease, as well as the influence of poor hygiene, filth, overpopulation, promiscuity, and prolonged contact.

Among Malays and Indonesians, the word for leprosy is kusta. It is interesting to note that this word is not of Malay origin, but a Hindu cultural borrowing. With the Hindu invasion and Hinduism, leprosy also penetrated these islands, giving it the name they did not have: kusta, a softened form of kushta.

In Japan, it dates back several centuries, and the oldest documentary sources already designate it by the name tsumí.

In Angkor (Cambodia), bas-reliefs have been found in the ruins of some temples that depict evident mutilating and deforming lesions of leprosy.

In Mesopotamia, among the Assyrians, Babylonians, Akkadians, Elamites, and Sumerians, the words saharsubbu and isurbaa were used to mean “body covered in scabs,” plagued and also covered in dust. The word eqpu was also known to designate a disease that destroyed the face and body, contaminated the patient, and made them impure and hideous in the eyes of others. This was leprosy, the worst punishment the gods could send to man. The word bennu was also used in Mesopotamia to designate leprosy.

Herodotus, the great historian and traveler, had already observed during his travels through Persia that certain people suffering from this disease, which filled them with pustules and gave them a poor appearance, were isolated outside the cities. They were probably lepers at times and at others suffering from dermatoses or dermatopathies in general, or various skin infections. Herodotus, writing 170 years before Christ, considers India as the place where leprosy originated. Before him, Ctesias, who was also a great Greek traveler (5th century BC), supported this same theory.

In Egypt, the Ebers Papyrus (1300-1000 BC), in addition to the Brugsch papyrus cited above, which compiles very early knowledge of Egypt, describes leprosy in its tuberculoid and lepromatous forms, with the names Chous tumors and Chous mutilations. Egypt has always been considered the place from which the disease reached the Western world. Ancient writings attribute the infection to the waters of the Nile (Lucretius, De Nat. Rer., VI, 1112) and to the unhealthy diet of the people (Galen). Several causes contributed to the spread of the disease beyond Egypt. First among the causes, Manetho cites the Hebrews, who, according to him, were a mass of lepers, whom the Egyptians managed to rid their territory of. Although it is a legend, there is no doubt that by the time of the Exodus, the contamination had affected the Hebrews.

Phoenician sailors brought leprosy to Syria and the countries with which they traded; hence the name “Phoenician disease” given by Hippocrates, arising from the fact that traces were found along the west coast of Greece around the 18th century BC and in Persia by the 5th century BC. The dispersion of the Jews after the Restoration (5th century BC) and the campaigns of the Roman army are believed to be responsible for the spread of the disease in the Roman world: Roman colonies in Spain, Gaul, and Britain were quickly infected.

¶ The disease-sin

From an anthropological point of view, the origin of disease, and of diseases in general, is attributed by different cultures to several causes:

- Offense against divinity.

- Offense against somewhat deified ancestors.

- Sorcery or foul play by a person with the power to do so.

- Transgression of a cultural taboo or prohibition.

- Penetration of a foreign body, visible or invisible.

- Abduction of the soul.

- Supernatural causes in general.

- Natural causes.

Ayurveda describes 18 varieties of leprosy, considering one to be of venereal origin, another to be due to cruelty to animals, another to be caused by having offended parents, ancestors, or divinities, by being bitten by poisonous animals, by greed, by gluttony, or by the frequent ingestion of food.

Whether through the transgression of a law or taboo, or through the offense against divinity, the guilty party is left stained, impure, and contaminated.

This concept has been considered oriental, and to say oriental is a very vague thing to say, especially after observing, studying ethnic groups in America, Africa, Oceania, and Asia, that all those we call primitive have this idea as a common element among their most deeply rooted traditions.

Among the Shinto of Japan, sin stains the soul and the body. If a skin disease appears, and especially tsumí or leprosy, the impurity of sin accompanies the sufferer for the duration of the illness.

The same attitude is evident in Tibet, Nepal, Indochina, Burma, Siam, and Korea: anyone who presents a repugnant skin disease has sinned.

Sickness-sin, sickness-guilt, sickness-stain, which requires purification, purging, cleansing, is an archaic concept, one of the most archaic in humanity. Probably the earliest study and knowledge of Eastern customs has led to this idea being attributed to the Orientals in ancient European literature, but after getting to know those we call “primitives” on all continents, we can assert that this idea has been present in humanity since a prehistoric and preliterary period. Therefore, Hebrew tradition could not be unrelated to this concept of illness-impurity or illness-God’s punishment.

The study of this tradition, contained in the Old Testament, and its dissemination not only among the Hebrew people but later in derived religions, Christianity and Islam, makes this idea of illness-God’s punishment manifest in all its force.

In the 20th century BC, the Hebrews left Ur, in Chaldea, and traveled through the Middle East for almost three centuries. They likely brought with them leprosy and the idea of illness as sin, illness as impurity, and punishment. This is evidenced by the oldest books of the Israelites. After their captivity in Egypt, the Exodus began, and Leviticus appeared, another of their books of laws, written by Moses, in which he codified and compiled all the medical knowledge they had acquired in Egypt, both preventive, curative, and religious. The filth that the Hebrews were forced to endure due to the lack of water while crossing desert areas must have caused numerous and frequent skin diseases, and this was the reason why Moses devoted such an extensive chapter to skin conditions, which he grouped under the common denominator of zara’ath or tsara’ath. He mentions leprosy in men, in garments, and in dwellings, and relates all of them to sin (Lv 13:2-7,9-17,25). Leprosy must be diagnosed by the priest who declares the person suffering from it unclean (Lv 13:28,47-59,35-36).

The religious significance of leprosy will continue to exist in the West based on biblical knowledge and propagated by the Levitical concept of impurity. From the Old Testament it will pass to the New, where the idea that leprosy is purified continues, although Jesus heals the lepers (Lk 5:12-16), separating for the first time the concepts of healing of the body and spiritual health through faith (UB 141:4.4-9). Thus this concept of religious disease will continue in Christianity for many centuries.

¶ First Greco-Roman descriptions

The word leprosy, which as stated is Greek, is already found in the Corpus Hippocraticum (Aphorisms, III, 20; De Usu humidorum and Epidemias, 21), but associated with psoriasis, eczema and other skin diseases. The true leprosy, which was already known to the Greeks, is described, as already stated, with the name elephantiasis.

During the time of the Emperor Augustus, Celsus gave a detailed clinical description of true leprosy, or “elephantiasis graecorum” (III, 251). Celsus says: “A disease almost unknown in Italy, but widespread in certain countries, is what the Greeks call elephantiasis, which is listed among chronic diseases. It affects the entire physical constitution of the patient, to the point that even the bones are altered. The surface of the body is covered with numerous spots and tumors, whose red color gradually takes on a blackish hue. The skin becomes uneven, oily, thin, hard, soft, and scaly; the body becomes thinner, the face swells, as do the legs and feet. When the disease has lasted for a certain period, the fingers and toes disappear, as it were, under this swelling.”

Another description is that given by Aretaeus of Cappadocia of the disease he calls leontiasis, which are the lesions of true leprosy on the face that, in addition to taking on an appearance resembling a lion’s face, suffer bone destruction. He also calls it satyriasis, due to the parchment-like skin and sexual appetite observed in patients.

Pliny, in his Natural History (XXVI, 51), notes that elephantiasis was a new disease in Italy, imported from Egypt during the time of Pompey the Great (10-48 BC).

Galen does not speak much about leprosy. As Mettler will say, in his time the confusion between elephantiasis and the Greek lichen was beginning.

¶ Etiology

Historically, we must mention the aforementioned belief in the disease as punishment from the gods for an offense or transgression of the law.

Serapion believes that leprosy is caused by liver disorders and can also be acquired through sexual contact (this leads us to suspect that there was confusion between leprous and syphilitic lesions).

Medieval doctors in Europe thought that the cause of leprosy was fish and milk. Engelbreth believed that the cause was goat’s milk, believing that leprosy was a variety of goat tuberculosis.

It was not until the 19th century that a special individual susceptibility was considered, and Hansen’s bacillus, directly responsible for the disease, was discovered.

¶ Leprosy in the Bible

Apart from the legislation on leprosy contained in Leviticus, already cited, and in the Pentateuch, it is also stated that “Many lepers were in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha” (Luke 4:27).

For the diagnosis of leprosy, Leviticus gives certain rules to the priests. “When a person has any scaly or white spot on their body, if the hairs have turned white and the affected area is deeper than the rest of the skin, it is a plague of leprosy.” Therefore, the sick person is considered unclean and, because of this, they had to live separately from others, outside the camp.

One of the most notable quotes from the Bible regarding leprosy is that of Moses (Ex 4:6-7). “The Lord said to Moses, ‘Put your hand back into your bosom.’ So he put his hand back into his bosom; and when he took it out, behold, his hand was leprous like snow.” And he said, “Put your hand back into your bosom.” So he put his hand back into his bosom; and when he took it out, behold, it was turned back like other flesh.”

The Scriptures, in Lv 13:1-9,44-46 define the double nature of leprosy, which includes that which spreads through the skin, covering it entirely, from head to toe, and speaks of the most innocent leprosy because it has all become the same, and the man is then declared clean. On the contrary, if any flesh was visible in him, he would be declared unclean by the priest, because anyone who was stricken with leprosy was considered unclean. “The Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron, saying: When a man has in his flesh a scaly spot, or a cluster of spots, or a bright white spot, and the plague of leprosy appears in the skin of his flesh, then he shall be taken to Aaron the priest, or to one of his sons the priests. The priest will examine the skin of the flesh and if he sees that the hairs have turned white and that the affected part is more sunken than the rest of the skin, it is the plague of leprosy and the priest who examined him will pronounce him unclean.” On the other hand, the Bible tells us that if the spot found was white and the skin did not sink nor the hair change color, the patient would only be secluded for seven days, examining him again after this period in order to verify that the disease had not spread. If so, he would be secluded for another seven days, until a second examination by the priest, declaring him clean if the characteristics of the lesion did not spread during that period. On the contrary, if it had spread, the patient would be declared unclean, since that, without a doubt, was leprosy.

Having a scaly disease that completely covered the patient from head to toe and made them look white would make the patient considered pure, since white has been the color of purity since time immemorial. On the other hand, areas of raw flesh were interpreted as impure, and those who suffered from them had to live outside the camp.

The Bible tells us about Miriam, Aaron’s wife (Numbers 12:9), who, speaking to her husband, had murmured about Moses. “The anger of the Lord was kindled against them, and the cloud departed from the Tabernacle. And behold, Miriam was leprous, like snow. And Aaron looked at Miriam, and behold, she was leprous. And Aaron said to Moses, ‘Ah, my Lord, do not lay this sin on us, for we have acted foolishly and have sinned.’” May she not now be like one stillborn, whose flesh is half consumed when it comes from its mother’s womb." Moses asks Yahweh to heal her, and Yahweh replies that she must first remain outside the camp for seven days, after which she will return to the congregation. After that time, Miriam rejoins them, but the Bible does not tell us whether she returned healed or not.

Another case of biblical leprosy is that of Naaman the Syrian (2 Kings 5:1-7), “A commander in the army of the king of Syria, who was a great man in his lord’s eyes, and he was highly esteemed because through him the Lord had given salvation to Syria. This man was exceedingly mighty, but he was a leper.” An Israelite girl, whom he had captive as a servant to his wife, advised him to call the prophet of Samaria and then “he would cure him of his leprosy.” When Naaman learned of this, he told his lord, and he gave him permission to go to Israel and be cured. He sent letters to the king of the Israelites and gave Naaman money and provisions for the journey. The letter said: “I am sending my servant Naaman to you, so that you may cure him of his leprosy.” In Israel, the prophet Elisha ordered him to wash seven times in the Jordan, “And your flesh will be restored, and you will be clean.” This did not please Naaman very much, who had hoped that by touching the prophet’s hand his illness would immediately be cured. Despite his displeasure, he obeyed the prophet, “and his flesh became like the flesh of a child, and he was clean.” When he presented himself to Elisha, the latter set as a final condition that he would worship only Yahweh, the God of Israel. In the same biblical episode, Gehazi, Elijah’s servant, seeing that Elijah was unwilling to charge him anything for the cure, his greed aroused, used a ruse to convince Naaman to give him two talents of silver and two new garments. But Elijah discovered his deception and punished him, saying: “Naaman’s leprosy will cling to you and your descendants forever.” And he went out from him a leper, white as snow.

This paragraph clearly alludes to the contagiousness of leprosy and its heritability, even if it is not true leprosy, something that is always doubtful in these biblical passages where it is said that the skin turns white, and which makes one think of psoriasis.

We also read the case of King Azariah (2 Kings 15:5), whom «Yahweh struck the king with leprosy, and he was leprous until the day of his death and lived in a separate house, and Jotham, the king’s son, was in charge of the palace, governing the people».

King Uzziah or Ozias (2 Chr 26:21-23) “was a leper until the day he died, and he lived as a leper in a separate house, so that he was excluded from the house of Yahweh.” This Uzziah or Ozias, with a different name, is the same Azariah of 2 Ki, who when he felt powerful “rebelled against Yahweh.” The name Azariah is given to the temple priest who criticizes the king for having burned incense in the temple, which was the priests’ duty. King Uzziah became furious “and in his anger with the priests, leprosy broke out on his forehead in front of the priests in the house of Yahweh, beside the altar of incense.” They made him leave the temple and he “hurried to leave, because Yahweh had struck him. So King Uzziah was a leper until the day he died, and he lived in a separate house, being leprous, and was excluded from the house of the Lord. And Jotham his son was in charge of the royal house, ruling over the people of the land.

There are also four unnamed men with leprosy (2 Kings 7:3) at the gate of Samaria. At one point, they apparently grow tired of living excluded, outside the city, and they say to one another, “Why should we stay here until we die? If we try to enter the city, because of the famine that is there, we too will die; and if we stay here, we too will die.” They decide to leave for the Syrian camp, where they prefer to risk being killed over the possibility of finding food.

Job’s illness may have been leprosy, but this word is not recorded in translated editions of the Hebrew. However, when Satan tells Yahweh to punish him in his own body and “touch his bone and his flesh to test his faith,” Yahweh gives Satan permission to test him. And he afflicts Job “with a sore boil from the soles of his feet to the crown of his head,” which must have made him very itchy, for Job even took a potsherd to scratch himself. “I go about blackened, but not by the sun,” Job says, speaking of his illness, and he repeats, “My skin has turned black and falls off, and my bones are burning with heat.”

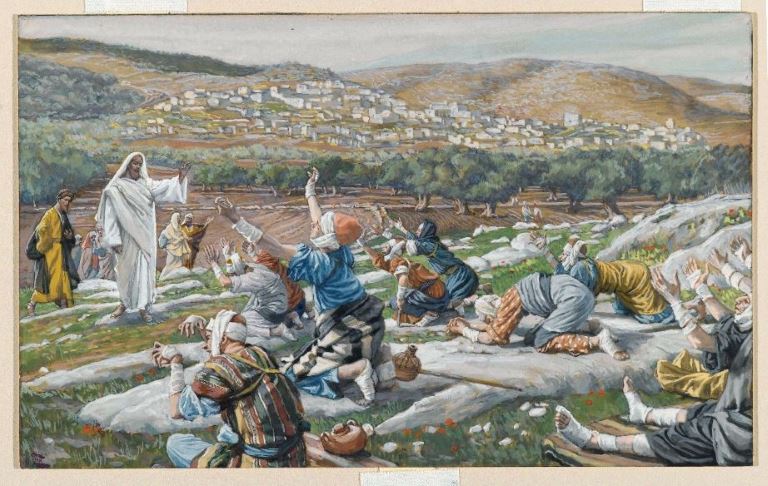

In the New Testament, Jesus heals a leper (Mt 8:1-41): “And, behold, a leper came and worshipped him, saying, Lord, if you are willing, you can make me clean. Jesus put forth his hand and touched him, saying, “I am willing; be clean.” And immediately his leprosy left him. Then Jesus said to him, “See that you tell this to no one, but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer the offering that Moses commanded, as a testimony to them.” This passage is also described in The Urantia Book (UB 146:4.3-5) and it is made clear to us that this was a genuine case of leprosy. This same episode is recounted by Mark (Mk 1:40-45) and Luke (Lk 5:12-16). In Matthew (Mt 11:5) it is said that “the lepers are cleansed by Jesus.” Finally, another character related to our topic is Simon “the leper” (Mt 26:6), since it says “while Jesus was in the house of Simon the leper” in Bethany. It is to be assumed that, if he was a leper, he was cured, otherwise he could not have remained in his house, according to the law. The Urantia Book, however, does not mention that this Simon of Bethany was a leper (UB 152:7.1, UB 172:0.1, UB 172:1.2, UB 172:2.1-3, UB 173:5.5, UB 174:0.1).

¶ Leprosy and Its Names

Besides the already mentioned names of elephantiasis among the Greeks and Arabs, and tsara’ath among the Hebrews, leprosy was called “Saint Lazarus’ disease” or “Saint Lazarus’s illness” after Lazarus the beggar, who in the Gospel parable, his body covered with sores, had to fight with the dogs for the scraps from the rich man’s table (Luke 16:19-31, UB 169:3.2).

But another notable fact in the history of diseases is that this beggar Lazarus is identified, it is unknown when or how, with another evangelical Lazarus, the Lazarus of Bethany, the friend of Jesus, brother of Martha and Mary, whom Jesus resurrects in another evangelical passage (Jn 11:1-44, UB 167:4.1-2). From here some leper hospital in England such as the one in Sherburn, which was very famous, was called “Hospital of Saint Lazarus and his sisters Mary and Martha”, and in other places in England, the name of Saint Lazarus disappears to remain only that of Martha and Mary, under whose invocation most of the lepers and leper hospitals of medieval England are placed. Mary was later identified with Mary Magdalene, and the name Martha disappeared, thus creating the hospitals of “La Magdalena” and “Mawedelyn” or “Maudlin,” which in France would be “La Madeleine.” For example, the leper hospital of St. Mary Magdalene in Totnes, Devon.

In many other places, Saint George emerges as the defender of lepers, due to the image of his spear and the dragon he destroys. This allegorical scene was seen as a vivid representation of what was intended to be done with leprosy, of the fight against leprosy. It was in the Nordic countries of Europe that leper hospitals were placed under the patronage of Saint George, and he was considered the patron saint of lepers.

In Spain, lepers are called “sick with the disease of Saint Lazarus,” “lazrados,” and also “malatos,” from which come the words lacería and malatería, names applied to leper hospitals or leper houses.

Gafo has been another widely used word to designate lepers, and gafedad refers to leprosy, due to the gafa hand or the forced flexion of the fingers on the palm, although this type of lesion is not only present in leprosy but also in other pathological processes such as chronic deforming rheumatism.

The word gafo and its derivative gafe were used as derogatory terms and equivalent to someone who brings bad luck. Being gafe is like being jetattore or being a bad shadow. Perhaps derived from or related to this is the word cahot or cagot or cacot used in France and the Spanish Pyrenees to designate lepers and, by extension, an ethnic group, the agotes or agotak, a marginalized group long considered a cursed race that inhabits the deep valleys of the Pyrenees. They were also called christiaas, cailluands, colliberts and caeths.

Lai in China, tsumí in Japan, isurbaa and eqpu in Mesopotamia, kushta in India, kusta among Malays, Indonesians, and Filipinos, likprar in Iceland, and mai-pake (Chinese disease) in Hawaii are other names.

In Portugal, leprosy has been called alvaraz, elefancia dos arabes, mal de San Lázaro, gangrena seca, Pida, figado, gafa, gafeira, gafem, guafem, and gafidade. Those affected by this disease were called elefantiacos, leprosos, gafos, lázaros, lazarinos, and manetas.

¶ Treatment

We know that both in Asia and among the Hebrews themselves, the appearance of a case of leprosy was immediately followed by a decree of separation and expulsion of the sick person from the limits of the village, camp, or city.

In the East, they underwent treatment with various products, from mercury to chaulmoogra oil (China, India).

The separation of lepers from healthy people was used as a means of prophylaxis or to prevent the impurity of the affected person (punished by the gods) from reaching the healthy. People suspected of suffering from leprosy were reported to the city authorities, who, through a jury—sometimes municipal in medieval cities, or through the priests themselves in biblical times—had to diagnose the condition, the veracity of the report, and act accordingly. The jury was ecclesiastical in many regions of Europe; elsewhere, a doctor’s diagnosis was required, who was then required to issue a certificate to the suspected patient.

From ancient practices and measures of hygiene and prophylaxis through isolation, to the burning of houses where a leper had lived, to the present day, there have been many and varied attempts to treat and cure leprosy.

In ancient China, acupuncture, as well as various mineral substances, including arsenic, were used to cure leprosy. In the 19th century, snake broth, especially the Cuban boa, was believed to be an excellent remedy for leprosy, as was turtle broth.

In India, chaulmoogra oil has been used successfully since ancient times. Ramah apparently already knew it as kalow. According to Valmiki’s Ramayana, it was used to cure the leprosy he had contracted that forced him to withdraw from humans and live in the forests. This kalow of Ramah has been identified with a plant from the Flacurtiaceae family, Taraktogenes kurzii. Extracts of Hydrocarpus wightiana were used in Burma. Both plants produce chaulmoogra oil.

It seems strange that the species reached Europe, but chaulmoogra oil, known since such ancient times, did not reach it from the East. It was only in the 19th century, thanks to the observation made by the Englishman Mouat in 1854 (others say that Roxburg had already observed it in 1814), that the curative effect of this treatment, which the Hindus had known about for no less than two thousand years, was proven.