© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ Imperial Taxation

In Jesus’ time, there were no nations as we understand them today, but empires and vassal states. The empire that governed the Jewish destinies was the Roman one, and by the time of Jesus, the more or less extensive kingdom that Herod ruled until 4 BC was divided upon his death into a set of tetrarchies (divisions of a lower rank than the kingdom). Herod Antipas took charge of Galilee and Perea; his brother Archelaus, and later a Roman prefect, took charge of Samaria, Judea, and Idumea, in this case forming an ethnarchy; Herod Philip of Batanea, Panias, Gaulanitide, and Trachonitis; Salome, a sister of Herod, from the cities of Jamnia, Azotus, and Phaselis. Moreover, within these territories, there existed an area called the Decapolis, a league of independently governed cities.

The ultimate governing power lay in the hands of the emperor and the Roman aristocratic families. They were the ones who exercised the right to collect taxes in their annexed territories, and in the event of rebellion, they relentlessly sent their troops.

But tax collection, which was the central axis conditioning the economic life of the period, was not carried out in a simple and direct manner, but rather unfolded through a web and a hierarchy of positions until it was imposed on the common inhabitant.

This hierarchy can be summarized as follows:

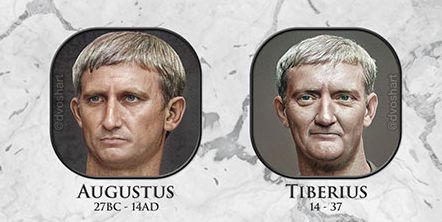

¶ 1. The emperor and the aristocracy

The emperors were the biggest billionaires of the time, thanks to the disproportionate income they derived mainly from direct annual taxes levied by their client kings on land tenure and personal property (Mk 13:12-17, BJ II:403 and 405). Secondly, they were enriched by indirect taxes of various kinds, including customs fees at ports and roads (Pliny, Natural History 12:32,63-65). Finally, they were beneficiaries of the wills of their client kings, and this last source was by no means negligible. Josephus reports that Herod the Great, for example, bequeathed Augustus 1,000 talents (about 6 million denarii), and Augustus’s wife Julia 500 talents (AJ XVII:146,190). Suetonius says that in the last twenty years of his reign, Augustus received 1.4 billion sesterces from wills (Suetonius, Augustus 101).

The silver talent, which was actually a measure of weight (35 kg), corresponded roughly to 6,000 drachmas in ancient times, and to the same number of denarii. But this measure of money was not very precise and fluctuated in Jesus’ time.

¶ 2. Client Kings and Prefects

Below the emperor were client kings, such as Herod the Elder, and then his sons Archelaus, Herod Antipas, and Herod Philip. Similarly, if it was inconvenient for a local king to rule, the emperor could employ Roman governors. During Jesus’ lifetime, this is what happened to the ethnarchy of Archelaus, which passed into the hands of a Roman prefect.

As for Herod the Great, he gained a reputation as a spendthrift. Josephus says of him: “Since he spent more than his means allowed, he had to be harsh with his subjects.” His substantial tax revenue earned him considerable enmity among the people. His son Archelaus, like him, overstepped his bounds in these matters and mismanaged his ethnachy so badly that Augustus did not hesitate to depose him, exile him, and confiscate all his property, installing a Roman prefect.

Both client kings and prefects had to earn the emperor’s trust. Their office was not for life. They knew that they could be deposed at any moment and replaced by another more trusted sovereign. Therefore, they had to be ready to please the emperor by flattering him in every way. For example, Antipas built Tiberias in honor of the Emperor Tiberius, and his half-brother Philip rebuilt Bethsaida, renaming it Julias after a daughter of Caesar, according to Josephus.

Each administrative division had annual revenues levied. Archelaus was required to pay 600 talents, or 3.6 million denarii (as mentioned by Flavius Josephus in AJ 17:318); Herod Antipas 200 talents, or 1.2 million denarii; Philip 100 talents, or 600,000 denarii; and Salome 60 talents.

However, these were the amounts at the death of Herod the Great, when his kingdom was divided into tetrarchies by Augustus. Quite possibly, by the time of the adult Jesus, thirty years later, these taxes were considerably higher. We can deduce this by noting that the 960 talents required across all the tetrarchies became 2,000 talents (more than double!) under Agrippa I, during the time of Caligula, 38 AD (AJ 19:352). Therefore, by the year 30 AD the 960 talents had probably already become about 1,500.

On the other hand, petty kings and prefects also took their personal cut from tax collection. They were required to deliver the required amount to the emperor, but in reality, they charged the people higher, sometimes truly exorbitant, percentages, so that those 1,500 talents could easily become 2,000. The profit of 500 talents would swell the private coffers of these client kings and governors. This huge sum of money represented a good fortune that often allowed these individuals to live in luxury and extravagance. Herod Antipas was the epitome of a foolish king who earned the enmity of his people for his constant excesses. It is not surprising, then, that frequent protests arose among the Jewish people (BJ II:4; Tacitus, Annals 2:42). Josephus calls Herod Antipas a “lover of luxury” (AJ XVIII:245). Since Josephus himself was situated among the urban elite, this comment must be taken as critical, meaning that Herod Antipas “was very excessive.” His half-brother Herod Philip, on the other hand, seems to have ruled his tetrarchy with somewhat more restraint.

For the sake of comparison, a denarius was the daily wage of a common laborer. A legionary in the Roman army would have been paid two denarii a day. The 500 talents that the tetrarchs could accumulate each year for their private coffers, or 3 million denarii, represented a disproportionate fortune.

¶ 3. Chief tax collectors

These were the ones to whom the client kings and prefects directly handed over the collection rights. Without a doubt, they took a very substantial part of the operation by raising the tax, which was already increased with the extraordinary surcharge applied by the rulers. As we will see, the tax was increasing through a good number of intermediaries, so that the final payers had to bear a much higher tax than that set by the emperors.

They were called architelonai. We have an example mentioned in the Gospel with Zacchaeus of Jericho (Lk 19:1-10). Jericho was the capital of one of the toparchies of Judea (a toparchy is an administrative division just below the tetrarchy, for tax purposes), so Zacchaeus held a position of importance. Curiously, Lk 19:10 proves that these chief tax collectors enriched themselves beyond belief on commissions. Zacchaeus says: “Lord, I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anyone, I will pay back four times as much.” This man must have amassed a lot of money to make such a statement. (It is interesting to consider how Pilate, the ruler of Judea, must have felt when one of his architelonai in Jericho suddenly decided to become an altruist. We do not know what became of Zacchaeus, but it is unlikely that his sudden change of behavior allowed him to continue in office. Rulers needed unscrupulous people in these positions. UB 171:6.1-3)

The parable that follows the story of Zacchaeus in Luke’s gospel (Luke 19:11-28) also has a great deal to do with these chief tax collectors. It is a veiled reference to Herod Archelaus and his attempt to obtain the crown from Augustus. The servants of the would-be king are actually the architelonai. As can be seen from the parable, these chief tax collectors had to have a very good business acumen, since they had to deliver not only the amount demanded by the emperor but also the extra amount demanded by the local ruler. Therefore, they had to be experts at making productive investments and making their money grow. Otherwise, there were no second chances, and the position was given to someone else. These positions, despite being frowned upon among the Jews, were nevertheless highly coveted. (Out of curiosity, the mina in the parable should be translated talent. A mina was only one-sixtieth of a talent. That means that the levy of a king like Archelaus must have been 36,000 minas. The king leaving one mina to an architelonai did not represent a large amount of money. The talent measure is correctly used in Matthew’s gospel. Mt 25:14-30)

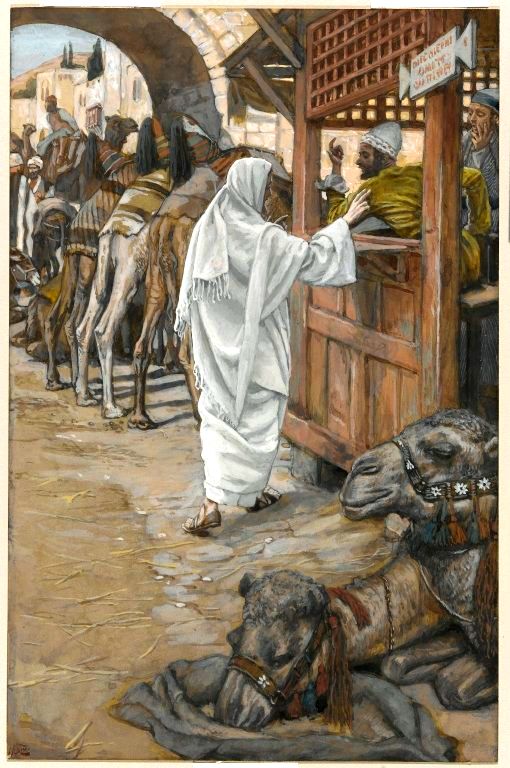

¶ 4. Tax collectors and customs officials

The architelonai actually sold their tax-collecting rights to local tax collectors, who then raised the tax further for their personal gain before finally imposing it on the citizens. To do this, it was required that every eligible person (over the age of sixteen) be registered on some type of census (UB 129:1.8). There were censuses of persons, censuses of property, and censuses of industrial activities. The collectors had these censuses and kept them up to date. No one could work without being registered on some census. The collectors literally hunted down defaulters and went from house to house demanding tax. To this end, they had a large staff of officials charged with collecting those who did not voluntarily present themselves for payment.

Taxes were levied, therefore, on possessions and goods (tributum soli), on production, and on persons or the poll tax (tributum capitis). If an entrepreneur employed laborers or slaves, he would retain a portion of their wages for the payment of this latter tax. Payments for the production tax could be made in kind. This payment in kind was frequently made for grain harvests and wine.

When the laborer could not pay the tax, these collectors also acted as lenders, advancing the money in the form of debt that later had to be repaid with hefty interest.

But these are only direct taxes. There were also a good number of indirect taxes, levied on the use of bridges and roads, the transport of goods (where each product had its own price), the use of water from aqueducts, the use of port facilities, and much more. For the collection of these taxes, there was also a large corps of publicans (publicani), or custom collectors. Most likely, Matthew the apostle was one of them (UB 139:7.3).

Customs rates were 2%, 2.5%, or 5%, depending on the goods; and this 2% rate (more or less) is exemplified by one of the technical terms for “customs collectors”: pentêkostologos (“the collector of the fiftieth”; Athenaeus, The Deinosophists 2:49; 11:481). Toll fees for roads varied considerably; they were also levied on animals (at different rates for camels and donkeys) and on carts. Presumably, the rulers collected considerable sums from local traffic on roads and bridges. The construction of these infrastructures, funded by kings and emperors, was not undertaken to satisfy the populace, but rather the upper class. For the common people, they served only a fiscal function. A toll list from Coptus, Egypt (90 AD) shows tolls, providing some idea of first-century rates in a Roman province. They cover different classifications of people based on sex, position, and profession (e.g., 5 drachmas for a male sailor, 20 drachmas for a female sailor); and different types of transport (e.g., 1 obolus for a camel, 4 drachmas for a covered wagon). Another example: the import duty for bringing seasoned fish to Palmyra in 137 AD was 10 denarii per camel load.

¶ Religious Taxes

In addition to this stifling economic situation at the time, there was also the payment of obligatory religious taxes to support the priestly class and the Temple in Jerusalem. This payment was made both in coin and as a percentage of production, or tithe.

There were several religious taxes that were required to be paid annually:

- One from the production of the land and livestock,

- another for the maintenance of worship, known as the “half shekel” or didrachma,

- and finally, other smaller taxes, such as the one used to purchase firewood for the altar.

Worthy of special mention are the taxes due to the birth of firstborn children.

¶ Tax from the products of the land

This tax included several items that could be paid in cash or in kind. It was from this tax and the one from livestock that the priests obtained their greatest income. It was made up of the following:

- The firstfruits or bikkurim. It affected the so-called “seven species,” that is, the seven main crops in Palestine: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and honey. If one lived near Jerusalem, one brought the fresh produce, and if one lived abroad, the dried one. It is striking that despite being a tax, the people organized festive processions with great fanfare to carry the load. Garlands were placed on the baskets, a caparisoned bull marched at the head to be sacrificed, and the procession was received in the temple atrium by the Levites. Each participant then handed over their basket while intoning a passage from Deuteronomy. Perhaps this festive atmosphere is due to the fact that the people, despite knowing it was a tax, still viewed it as a religious offering in gratitude for the harvest, which must have been its original meaning.

- The terumah. This included not only the seven kinds of firstfruits, but also the fruit of the trees. This primarily affected wheat, wine, and oil. An average of one-fiftieth of a person’s annual income had to be paid. This payment was surely seen more than the previous one as a payment to the priests, although both were actually payments, since these firstfruits could only be consumed inside the temple by the priests. Their families could not benefit from it.

- The tithe. This was the most important and largest amount. It affected everything, even the smallest items the farmer could produce, of which a tenth had to be paid annually. The Gospels show in some passages the excessive scrupulousness applied by the priests in determining whether the product was eligible for tithing or not. Even the least valuable produce, such as mint, dill, and cumin, had to be taken into account (Mt 23:23; Lk 11:42). This tax was intended for the Levites, or second-ranking ministers of the temple, but the priests had devised a ruse to get their hands on some of the spoils. A tenth of what the Levites received was for the priests. And this part could be used by the entire priestly family.

- The second tithe. It was not intended for either the priests or the Levites, but even so, it was another tax that completely undermined the domestic economy of the time. It was another tenth of everything produced, which had to be taken to Jerusalem and consumed there at sacrificial banquets.

- Finally, the “dough offering” or hallah. It affected dough made from wheat, barley, spelt, oats, and rye. The dough was handed over, not the grain. An ordinary citizen had to hand over one twenty-fourth of the total, and a baker one forty-eighth of the total.

If the percentages of each tax are added together, it can be seen that the total contribution represents a little more than a quarter of all agricultural production!

¶ Tax from Livestock

The most important tax was the surrender of the firstborn male of livestock. In the case of animals suitable for sacrifice (bulls, rams, and goats), it had to be delivered in kind. If they had no blemishes, they were sacrificed, their blood was sprinkled on the altar, and the fat was burned. The priests kept the remainder and could consume it in Jerusalem as they wished. If they had blemishes, then the entire animal became the property of the priesthood. As for unclean animals (horse, donkey, and camel), a sum of money had to be paid as a ransom. For a donkey, a sheep had to be paid. The amount was about one and a half shekels for each animal.

There was also a shearing tax for owners of flocks of sheep. It was about five Judean shekels or ten Galilean shekels.

¶ The “half shekel”

It had to be paid in the ancient Hebrew or Tyrian (Phoenician) currency. The time set for payment was the month of Adar (February-March) and it was usually collected by local collectors in the communities, who were then responsible for transferring their proceeds to Jerusalem. Every male Israelite over twenty years of age was required to pay it. Because the shekel was not a common currency, the people were forced to use money changers who carried out the conversion, levying a considerable amount on the exchange rate, causing the half-shekel to become almost three-quarters of a shekel.

The Talmud tells us that if a person went to the temple to pay their half-shekel tax with a full shekel, the priests would keep the entire shekel, demand an additional two kalbonot, and return a half-shekel to the taxpayer. The payment of the kalbonot was apparently justified because the priests would then have to exchange these coins with the money changers, who would then charge them for the exchange. Furthermore, by returning the half-shekel to the payer, they facilitated their payment for the following year. In the end, ordinary Jews could end up paying as much as a fifth of a shekel in exchange for the coins. (See UB 157:1.1, UB 173:1.3).

¶ Other taxes

Another tax was paid annually, specifically an annual offering of wood for the altar of burnt offerings. Any kind of wood was accepted, except olive and vine wood.

¶ The Redemption of the Firstborn

The firstborn son, that is, the first male child a woman had, was to be redeemed at the age of one month by paying five shekels (Numbers 18:15-16; Numbers 3:44ff; Neh 10:37; Ex 13:13; 22:28; 34:20). It was not necessary to present the child at the temple, contrary to what Luke 2:22 suggests. It was enough to send the payment to the temple.

¶ In summary

We can imagine the economic situation of an average peasant of that time, or a low-ranking merchant, if we assume an average income of 500 denarii per year, and we make the following list of taxes to be deducted:

| Concept | Denarii |

|---|---|

| Taxes on the monarch | 50 |

| Other taxes (roads, tolls, customs, etc.) | 25 |

| First fruits | 5 |

| Terumah | 10 |

| General tithe | 50 |

| Tithe for the poor or second tithe | 15 |

| Annual sacrifices for any cause (livestock, firstborn, etc.) | 9 |

| Annual tax for the Temple (taking into account the money changers) | 2.5 |

| Total | 166.5 |

That is, about 167 denarii, or 33%, or one-third of the income of a person with few resources, were spent on taxes alone, and he was also subject to the risks of climate and bad weather. We can imagine the discontent such a drain could cause among the population (UB 127:2.1), especially when they saw how the income, which the people had worked so hard to produce, was being squandered and wasted by their rulers.

¶ Conclusion

In short, the economic situation in Palestine at that time was very precarious, due primarily to the crushing taxes and the greedy bureaucracy that had been created around them. The workers of Jesus’ time earned just enough to live on; there was no surplus, nor was there any possibility of savings. However, this was a situation shared throughout the Empire. The Jews were not specifically taxed, and the citizens of that time, however indignant they might be, knew they could do nothing against an established power sustained by an iron-clad army that would inexorably fall at the slightest sign of anti-tax rebellion. Jesus was not indifferent to this situation, for he suffered it firsthand. His youth was submerged under a constant tax burden, with which he could barely cope (UB 126:5.5). They tried to trap Jesus into openly making statements against the Caesar tax (Mt 22:15-22; Mc 12:13-17; Lc 20:20-26), and he, with good eye, and knowing the lack of permissiveness that Rome had in these matters, avoided the direct answer. Should the tax be paid, or was it necessary to rebel against this situation? In the case of the Jews, there was a different background than in the rest of the peoples for positioning themselves against the Roman tax. The Jews did not especially resent the Caesar tax for simple economic reasons, but rather for a criterion of religious zeal. And it was this religious zeal, and not the amount of the tax, that finally unleashed armed rebellion against Rome on several occasions. But in general, the situation, although suffocating, was always accepted and endured in one way or another by all the inhabitants of that time.

¶ References

- Joachim Jeremías, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1977.

- Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985.

- Antonio Piñero, Año I. Israel y su mundo cuando nació Jesús (Year I. Israel and its World When Jesus Was Born), Ediciones del Laberinto, 2008, pp. 93-94.

- K.C. Hanson, The Galilean Fishing Economy and the Jesus Tradition, Biblical Theology Bulletin 27 (1997) 99-111.

- Flavius Josephus, Complete Works, Jewish Antiquities and Wars of the Jews, Editorial Acervo Cultural, 1961.

- Tacitus, Annals, Alianza Editorial, 2008.

- Pliny, Natural History, Editorial Cátedra. Universal Letters, 2007.

- Suetonius, Augustus, RBA Libros, 2004.

- Athenaeum of Naucratis, The Banquet of the Learned or Deinosophists, Gredos Classical Library, 2006.