© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ Importance of the Sea of Galilee for Jewish Fishing

The Jewish territory had almost no access to the sea. The Dead Sea was unsuitable for fishing, and of the extensive Gaza Strip and the Mediterranean coast as far as Phoenicia, none of the important fishing ports remained under Jewish influence for long. Of the cities of Gaza Maiumas, Anthedon, Ashkelon, Ashdod Paralios, Jamnia Paralios, Joppa, Apollonia Sozusa, Caesarea Maritima, and Dora, only Joppa could be considered a Jewish port, since in the rest its inhabitants were almost all Greeks or Gentiles. For this reason, in Jerusalem, the so-called “Fish Gate” (Neh 3:3) was so named because it used to be the place where merchants from Tyre and the Phoenician coast used to sell their product.

All this caused the Sea of Galilee, the small freshwater lake in the region, to become a fishing and industrial center of great importance for the Jewish world, since fish caught by Jewish fishermen, which were guaranteed to comply with rabbinic precepts of dietary purity and avoid fish considered impure, was preferred over that caught by Gentile fishermen. However, the existence of the “Fish Gate” in Jerusalem as a settlement for Tyrian fishermen means that fishing in the Sea of Galilee did not provide all the catches needed to supply Galilee, Judea, Perea and the rest of the territories under Jewish influence, and the inhabitants of Jerusalem had to accept the consumption of fish from Gentile cities.

The importance of the fishing sector in the economy of the Sea of Galilee is reflected in the names of toponyms, many of them with reference to this sector. Bethsaida, the population that scholars debate whether there was one or two, means village or house (bet) of fishermen (saidan). Tarichea, the town that many scholars today identify with Magdala (erroneously, as we have seen in another article), means “place where fish are kept.” In fact, the Sea of Galilee, in Jesus’ time, was also called the “Sea of the Taricheas,” because the fish-dried products produced in the lake were world-famous.

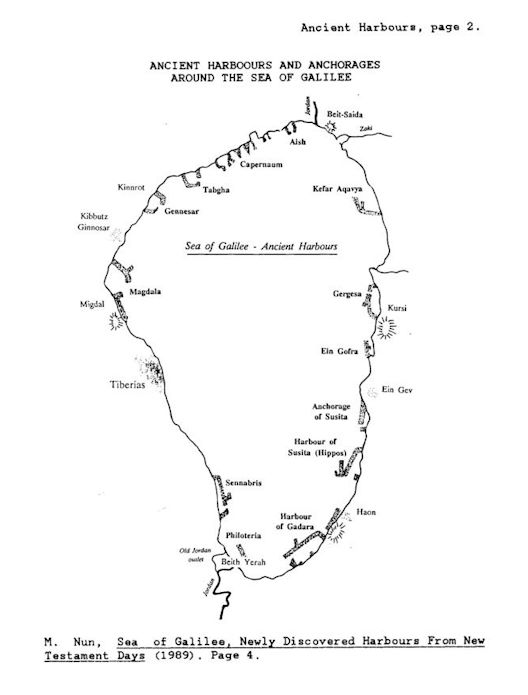

¶ Fishing ports at the time

During a prolonged drought in the 1980s, Sea of Galilee scholar Mendel Nun was able to identify the remains of ancient wharves from the time of Jesus. What is striking about these discoveries is that the Sea of Galilee was practically covered along its entire coast by these wharves. This suggests that a large number of small and large fishing villages were located almost seamlessly along the sea. Some of these villages, however, were minor enclaves or villages associated with a more significant settlement, on which they depended, but which were located further inland. The latter case corresponded to the ports of Hippos and Gadara, two independent city-states of the Decapolis, with a large chora or territory under their jurisdiction, which occupied a wide strip of the eastern part of the lake. Continuing clockwise from here, we have the following settlements: Tarichea was the southernmost, located at the mouth of the lake on the Jordan River; A little further north was Senabris, and then Hammat, the latter a place highly prized for its hot thermal springs; then came the new city of Herod Antipas, Tiberias or Tiberias; north of Tiberias was Magdala; on the northern side of the lake were the towns of Genesaret, Bethsaida, and Capernaum; it is possible that near the mouth of the Jordan there was a small village called Aish; crossing the Jordan, we entered Gaulanitide territory by paying a fee at the obligatory customs office; there, a few kilometers further on, we found its capital, called Bethsaida-Julias (it was called Bethsaida in ancient times but was later renamed Julias); south of Bethsaida-Julias, occupying the eastern coast, were three other towns: Kefar Aqbiya, Cheresa, and Ein Gofra.

As can be seen, there were a total of fifteen ports, a considerable number considering that the Sea of Galilee only had a perimeter of 50 km (today it is about 53 km, but in Jesus’ time the sea level was lower than it is today and the coastline was shorter).

¶ Economic model of the fishing sector in Jesus’ time

The productive economy of Jesus’ time in the Roman Empire was not a free market economy, but rather a controlled market economy. No industrial activity could be carried out without receiving state authorization, either from the emperor himself or from his subordinates (whether governors or client kings). Farmers, ranchers, fishermen, and artisans were all subject to a hierarchical power structure in which those at the top of the pyramid held all rights to control taxes and rents, and progressively, through an endless succession of intermediaries, reached the wage laborer and the slave, at the bottom of the hierarchy.

In these economies, the ultimate peasant and artisan had no say in the allocation of taxes, which were left entirely to the whim of the top leaders. For this proletariat, the only option was to submit to this rigid system or to evade taxes through lies or anonymity. However, a strict census system made evasion of these taxes difficult. In this situation, technological innovation was meaningless, since greater production also increased tax revenues in equal proportion. The only innovation permitted was in public construction, roads, canals, ports, or war materials, although these served only the aggrandizement of wealthy families and barely benefited small workers.

Focusing on the fishing sector, below the governors and client kings (who in Jesus’ time were Pontius Pilate and the other prefects of Judea, as well as Kings Herod Antipas and Herod Philip), the following organization was in place:

- First, these rulers auctioned the rights to collect taxes and leasehold rights to the “chief tax collectors” or architelônai. These were very wealthy individuals, as they had to be able to advance large sums, and they acted as bankers, but they were also responsible for leasing their rights to the next. Each governed a region or toparchy. In Galilee, there were four toparchies: Tarichea, Gabara, Tiberias, and Sepphoris.

- Secondly, the chief collectors sold their rights to second-class tax collectors, who were in charge of collecting taxes: renting or leasing rights to carry out industrial activity (for example, to be able to fish, a fishing fee or license had to be paid to a port chief, who authorized a family to fish); taxes paid to canning factories to be able to operate their business; tolls paid to transporters at ports and roads, especially when changing jurisdiction or for the use of an imperial road; finally, merchants had to pay taxes that allowed the sale of products to the consumer. These tax collectors exclude those who collected the obligatory tax for the Jerusalem temple (Mt 17:24) and other religious taxes required of all Jews, which were controlled by a network of tax collectors under the command of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. However, this autonomous Jewish tax collection was frowned upon by the Roman authorities, although accepted in theory. On several occasions, the Roman prefects did not hesitate to plunder the Sanhedrin’s coffers using any favorable pretext. In a certain sense, the prefects viewed this second tax collection as an intrusion and the cause of a decrease in their fiscal capacity.

- Third, there were groups or corporations with an industrial purpose: in many cases, these were simply families (for example, several fishermen from the same family organized fishing gangs or koinônoi that used the same boat, which could be owned by the family or leased from a boat owner); in other cases, they could be businesses owned by an entrepreneur who provided the investment money and others worked for him (such as canned fish factories or tariqueas).

- Finally, the salaried worker received his livelihood from the corporations to which he belonged. At the worst end of the spectrum was the slave, who could only receive room and board, but did not receive a single coin for his work until he was freed.

As for the types of professions related to fishing, there was a tangled web of professionals making a living from this activity:

- Fishermen were involved in obtaining fish.

- Fishing tools were involved in obtaining fishing gear: carpenters who built boats (shipyards); farmers who grew flax; weavers who used flax for nets and sails; and stonemasons who polished perforated stones to make anchors and weights for nets.

- In obtaining fish-derived products, salting fish required factories with large areas for drying, then winemakers who grew grapes and made wine to add to the preserves, salters or salt merchants, and potters to produce the vessels in which these preserves were transported.

- In the distribution of products, we have the market brokers, who bid to buy the catches to later resell them to distant merchants in another city; boatmen who transported the goods by sea; stevedores; caravan and cart drivers; guards who kept the shipments safe by protecting them from thieves; and the final merchants.

¶ Tenants

Fishing was not a liberalized activity, but rather was exercised as a right granted by tenants to whom these privileges were granted. Flavius Josephus is surely talking about them when he says “the elite and the urban rulers” during the Hellenistic period (AJ XII 4.3). And the term kômogrammatoi (AJ XVI 203) may refer to the village “bookkeepers” who oversaw these leases and other taxes. In short, the fishermen received capital along with fishing rights, and were therefore indebted to local brokers responsible for ports and fishing leases. These tenants were also very likely the owners of the boats and gear, so the fishermen only offered labor but had to rent out the rest of their work tools.

Records also indicate that there was (at least in some ancient locations) a fishery police (epilimnês epistatês; or what we might anachronistically call “game keepers”), who made sure that no one was fishing illegally (without a fishing contract) or selling to unauthorized middlemen.

¶ Fishing Societies and Fishing Families

Fishermen could form “cooperatives” (koinônoi) to bid on fishing contracts or leases. One of the most interesting observations the gospels make about the families of Jonah and Zebedee is Luke’s comment that they were a small-scale collective/cooperative:

“…they signaled to their partners [metachoi] from the other boat to come and help them. And they came and filled both boats… [Simon] was amazed, and all his men with him, at the large number of fish that they had caught; and likewise James and John, the sons of Zebedee, who were members of the cooperative [koinônoi] with Simon» Lk 5:7,9-10

Since it appears only in Luke’s gospel, this description may be due to the evangelist’s own experiences, rather than those of the fishermen. But evidence of guild fishing in Palestine exists for a slightly later period. Evidence has been found for an ancient Egyptian fishing lease from the Roman era, an Egyptian papyrus from 46 AD that identifies a fishing collective of thirteen fishermen and their scribe who took an oath to the Roman emperor (Tiberius) not to fish for sacred fish. And a fishing cooperative in Asia Minor provided an impressive stele dedicated to the tax office paid by the cooperative in 54–59 AD. This cooperative (or guild) at Ephesus included both fishermen and vendors, and this could be the model for cooperation between fishing families and vendors in Galilee.

¶ Types of Fishermen

Some authors consider that there were two social classes or categories among the fishermen of the Sea of Galilee: one would be those fishermen or businessmen who had salaried fishermen in their charge, and the other would be the lower-class fishermen who could not afford to have anyone on their payroll. In either case, both were frequently part of family cooperatives, as we have seen. We can appreciate the difference with Zebedee. The father of the apostles must have been in a comfortable financial position, otherwise he would not have been able to do without his sons for a few months.

If there were not enough family members in the cooperative, the fishermen had to employ workers to help with all the responsibilities: handling the oars and sails, repairing nets, sorting fish, etc. These workers represent the bottom of the social ladder in the fishing subsystem. In Mk 1:19-20 we find Zebedee as a fisherman who not only has two sons working in the business, but also employed workers (see UB 145:1.1). This number corresponds to the crew needed for the larger boats. Both agriculture and fishing made use of such laborers, who may have been day laborers, meaning their contracts expired at nightfall and they had to return to look for work the next day (e.g., Mt 20:1-16) or seasonal laborers (e.g., Jn 4:36). That these employed workers were a necessary and important part of the Galilean economy seems inescapable (e.g., Mt 10:10; Jn 4:36; 10:12-13). These types of associations can also be seen in UB 123:1.6, UB 128:5.8, UB 129:1.4, UB 139:1.1

¶ Types of Fish

Fish, in general terms in Jesus’ time, were classified as permitted and prohibited, that is, as pure and impure. The Mosaic Law (Lv 11:9-12) established that only vertebrate fish, with scales and fins, could be considered edible, while the rest were considered prohibited. This is the underlying reason for the text in the Gospel, in Mt 13:48, which speaks of good fish (permitted by law) and bad ones. At the end of each catch, therefore, the fishermen had to gather on the beach, and separate the impure fish, returning them to the water.

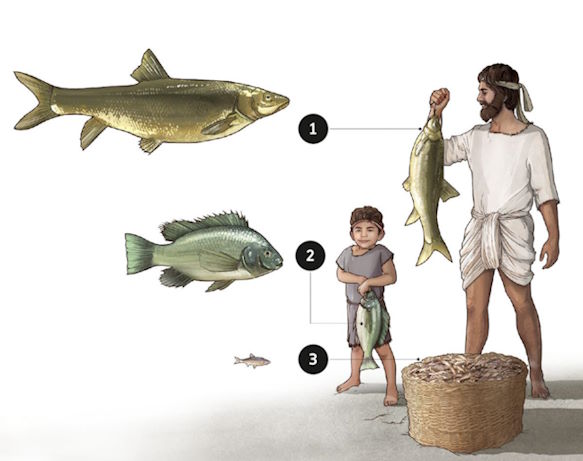

The Sea of Galilee has been famous for its fish since ancient times. There are eighteen species of fish native to the lake, which are locally classified into three main groups:

- Sardines. They are endemic to the lake. Currently, during the high season, tens of tons of sardines are caught every night. They resemble saltwater sardines and can be found in huge schools. They were widely used for canning. These sardines were an important part of the daily diet throughout the country, especially for those who lived near the lake.

- Biny. These sardines are made up of three species of the carp family. Their name comes from a Semitic word for “hair,” which must refer to the typical barbs on the edges of the fish’s mouth. These meaty fish are very popular at banquets and during Sabbath celebrations.

- Musht. In Arabic, “musht” means “comb,” and the five species it comprises are very famous because they have a long dorsal fin that resembles a comb. The largest and most common of these is the Galilean tilapia, also known today as the “Saint Peter’s fish,” which can reach a length of 40 centimeters and weigh 1.5 kilograms. Its flat shape makes it ideal for frying, and its easily separable flesh and few bones make it a popular choice for meals.

Sardines are often mentioned in the Gospels as “small fish,” in contrast to the other two species, which were larger. They are clearly mentioned in the miracle of the feeding of the four thousand. According to Mt 15:34 and Mk 8:5-7, “five loaves and a few small fish” were all that Jesus’ followers had to eat.

The miracle of the feeding of the five thousand appears in all four Gospels. Mt 14:17, Mk 6:38 and Lk 9:13 mention “five loaves and two fish.” But John’s version (Jn 6:9) is slightly different and specifies that the bread is barley and uses another Greek word for fish: opsaria (small fish) instead of ichthyes (fish). We can assume that these small fish are not the young individuals of the large species, but were sardines and therefore small by nature. These, with bread, in fact, constituted the usual diet of the local population.

There are several Gospel passages that suggest musht. When winter comes, this tropical fish congregates in schools in the northern part of the lake, where they are attracted by the warm water of the springs that flow into the lake. This attraction offers fishermen an opportunity for abundant catches. This fact could explain the miraculous catch mentioned in the Gospels (Luke 5:1-11). The Urantia Book gives us an explanation for this miraculous catch by referring to these schooling habits of fish (UB 145:1.2-3). An identical occurrence occurs in the passage UB 192:1.3-6.

In the spring, the mushts mate and lay their eggs on the lake bottom. After fertilization, the parent mushts carry the eggs in their mouths for three weeks until they mature. They then care for them for a few days, and then release them. To prevent their offspring from entering their mouths again, the parent fish ingest pebbles so that their former “home” will no longer be so comfortable. They may also swallow coins and other objects with the pebbles, and many coins have been found in the mouths of mushts. This might explain the passage where Jesus asks Peter to find a fish with a coin in its mouth to pay the taxes (Mt 17:24-27; UB 157:1.1-5).

In the Church of the Multiplication in Tabgha, which was built to commemorate the miracle performed by Jesus, two small fish are shown in a sixth-century mosaic. We see a basket with four loaves with a fish on each side. However, these fish do not appear to be from the Sea of Galilee. All fish caught in the Sea of Galilee have only one dorsal fin, while those shown in the mosaic have two dorsal fins. The artist who designed the Tabgha mosaic probably came from abroad to do his work and used a pattern without ensuring its correctness by taking a look at the fish in the lake.

¶ A well-known fishing suburb

There is a place on the lake that at that time, as today, had a special relationship with fishing. This is Tabgha, located two kilometers southwest of Capernaum. The name is a corruption of the Greek Heptapegon, or “Seven Springs.” And the name is quite accurate, because in the vicinity of Tabgha there is a group of springs that vary in volume, temperature, and salinity. Flavius Josephus referred to the largest as the “Spring of Capernaum,” thus indicating a clear connection between Heptapegon and Capernaum. In another article it has already been studied that this site of Heptapegon or Tabgha is actually one of the firm proposals that archaeologists made during the first campaigns to the Holy Land for the location of Bethsaida, the city of origin of the apostles Andrew, Peter, and Philip.

In winter, when the warm water leads to the heat-loving musht banks in the vicinity, the fishermen of Capernaum remained in this area until early spring, making Heptapegon an important commercial suburb of Capernaum. The small harbor that must have once served the fishermen was discovered in 1975.

Fishing Techniques

Various fishing methods have been used for centuries in the Sea of Galilee:

- a) Some fishermen caught with bare hands,

- b) some used spears, arrows, or harpoons,

- c) with a hook—a rod with a hook and a linen line. Peter and Andrew were said to have been fishing with a hook and line when they caught the fish with the coin in its mouth (Mt 17:27). We have already seen that in The Urantia Book we have a different narrative (UB 157:1.1-5).

- d) casting flax nets into the water;

- e) some used wicker baskets or other kinds of traps made of nets or snares.

While fishhooks are mentioned in the Gospels (Mt 17:27), the most common mode of fishing in Galilee seems to have been with nets. After the generic word “nets” (Mk 1:18-19) three different types are mentioned in the New Testament:

- the cast net (amphibilêstron), used both from a boat and from the shore (Mt 4:18); it is circular, about 7 meters in diameter, with control weights hooked on the edge. A man usually throws the net in a circle from the shore, but it was also done from boats. It required great skill since it had to open completely when it fell into the water to catch the fish underneath. Peter and Andrew were busy with this type of fishing when Jesus called them. The weights gather as the nets sink and surround the fish. Sometimes fishermen on a boat had to jump into the water to retrieve the net and this is why they so often fished naked. The disciples were probably fishing with cast nets when they discovered Jesus on the shore (Jn 21:7; UB 192:1.3-6).

- the much larger drag (sagênê), used from a boat (Mt 13:47). This is the oldest type of net. The net was made as a long wall 100 meters long and 4 meters high. The bottom of the net had weights with plumb lines, and the top end had cork floats. The net was doubled. A team of up to 16 men kept the loop securely attached to the drag. The boat would sail with another team until the net was fully stretched, then circle around and return to shore. Here, the second team would set foot on land and hold the loops. Both teams would then drag the net and its contents (in the best cases, many fish) toward the shore. This method made it possible to catch fish hiding at the bottom of the lake. The fish were then handed over for sorting, and the operation was repeated as many as eight times a day.

- The third method is the trap net, which actually consisted of three nets: two large mesh walls about a meter and a half high with a finer net in between. The boat would go out into deep waters where there were no stones so that the nets would not break. This was usually done at night. One end of the net was submerged in the sea, and the boat would make a circle that formed a kind of barrel in the water. The net caught all kinds of fish, as they were unable to escape through the three layers of netting. When the fish were brought to shore, they had to be pulled out of the nets, and this took time and skill. The nets were spread out on the rocks to dry and be repaired. Only in emergencies were they repaired on the boats. Thus we find James and John repairing their net on a boat (Mt 4:21).

Greek authors, such as Oppian and Aelian, mention up to ten different types of nets, but are unable to distinguish between them. Nets required a great deal of attention: not only did the fishermen and their employees make the nets, but after each haul out the nets had to be repaired, washed, dried, and folded (Mk 1:19).

¶ Tools for the Fishermen

For their work, fishermen needed the resources of farmers and craftsmen, including (but not limited to): flax for nets and sails, cut stone for anchors, wood for building and repairing boats, and baskets for fish.

As for baskets, they are called in Greek spuris (Mk 8:8) to a basket with handles, and kophinios (Mk 6:42) to a large basket that was used since time immemorial, carried by women on their heads.

As for boats, the gospels and Josephus speak of boats on the Sea of Galilee for fishing and transport. In 1986, an ancient fishing boat was discovered in the mud on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, just north of Magdala. It was a small boat, about 8.8 meters long, 2.5 meters wide, and 1.25 meters high. These boats, called ploiarion, allowed four to six fishermen to fish and comfortably maneuver the vessel. Large boats, or ploion, intended for transport, were 18 meters long by 5 meters wide and could accommodate a cargo of over a ton, including five crew members and cargo, or a crew of about ten passengers (Mk 6:45). They sometimes had a small shed in the stern.

The wood used to make the boats was of poor quality, sourced from the forests of the Golan Heights. For the keel, the finest wood, cedar of Lebanon, was usually reserved, but for the planks, they used whatever was on hand: pine, jujube, and willow. This made the boats extremely fragile to gales and the wear and tear of work, so they had to be constantly repaired with patches from other boats.

The need for these resources is often ignored by scholars when imagining Jesus’ activity in Capernaum. As a carpenter, he could well have worked in a shipyard specializing in the manufacture and repair of boats (see UB 129:1.2). Shipbuilding also attracted other subsidiary industries (pitch for caulking ships, paint, etc.).

¶ The Fish Canning Industry

The fishing trade also brought with it the fish-processing industry. During the Hellenistic era, seasoned fish had become a staple food throughout the Mediterranean, in both city and country. The result was the development of a distinction in trade between those who caught fish, those who processed fish, and those who sold fish. But as a stele from Ephesus shows, fishermen and sellers may have worked cooperatively. The distribution of the catch was also controlled by government-approved wholesalers. While fish processors are not explicitly mentioned in the Gospels, the use of seasoned fish is mentioned (John 6:9-11; also Tob 2:2). The Urantia Book also speaks of it at length (UB 68:5.5; UB 139:1.1; UB 139:12.2; UB 192:1.9).

Fish were processed for preservation and transportation by being cured, pickled, dried, or salted; and could be mixed with brine and wine. The Bible and the Mishnah also speak of various ways of eating fish: roasted or grilled (Lk 24:42; Jn 21:9; Tob 6:5), chopped (A.Z. 2:6), cooked with leeks (M.Sh. 2:1), with an egg (Beit. 2:1), or in milk (Hul. 8:1). Fish oil could also be used as fuel for lamps (Shab. 2:2) and as a medicine. The writer Athenaeus (c. 200 AD) speaks eloquently of the varieties and uses of processed fish (Deinosophists 3.116a-121d). He also mentions “sellers of processed fish.” In the work Geoponica (a Byzantine compilation of recent sources), we find the recipe for garum, a fish-based sauce that was all the rage in Roman times.

Garum, also called liquamen, is made this way: the entrails of the fish are placed in a vat and salted. Whole small fish are also used, especially smelt, or tiny red mullets, or small sardines, or anchovies, or any small fish available. The entire mixture is salted and placed in the sun. After it has aged in the heat, the garum is extracted in the following way: a coarsely woven basket is placed in the vat filled with the aforementioned fish. The garum is put into the basket, and the so-called liquamen is strained through the basket and collected. The remaining sediment is called allex. There were different variants of garum. Three famous ones were the Hispanic, the Bithynian, and the Judaean. Pliny the Elder identifies the Judaean with a particular variety of processed fish: castimoniarum (Natural History 31.95).

During the Roman period, fishmongers exported many varieties of processed fish, differentiated by the type of fish used, the parts of the fish, the process, and the recipe. The four basic types were garum, liquamen, muria, and allex. The terms salsamentum and salugo referred to the saline solution used for salting. Literary references and amphorae have shown that there were many categories of these products, the best being garum sociorum produced in Hispania (Pliny, Natural History 31.94).

The items needed for fish processing had to be supplied by merchants, farmers, and artisans, which led to a whole subsidiary industry. We have: salt, wine, amphorae, and possibly olive oil. The brine supplies undoubtedly came from the Dead Sea in the south or Palmyra in the northeast.

Preserved fish and fish sauces were distributed by merchants throughout Galilee and the rest of Palestine, as well as throughout the Mediterranean basin. This involved transporters and packers. The most commonly used distribution route was the Via Maris, which flowed into Capernaum in the north, skirted the western coast, and then branched west, probably once near Gennesaret and Magdala, through the Valley of Asochis and Cana, heading toward Ptolemais (Akko), or near Tiberias, heading toward Sepphoris and then Caesarea Maritima. In either case, they were searching for a Mediterranean seaport (hence the “sea route”).

Jewish amphorae with traces of fish sauce have been found in shipwrecks. In his description of a ship built for Heiron of Syracuse, Athenaeus states: “On board were loaded ninety measures of grain, ten thousand jars (keramia) of seasoned fish (tarichon), six hundred tons of wool, and other merchandise totaling six hundred tons” (Deinosophists 5.209)

¶ Jesus’ relationship with fishing

Jesus had personal knowledge of the lives of Galilean fishermen, as can be seen in Mt 7:9-10: “Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake?”

This reference to the stone and the snake seems taken from the everyday experience of fishermen, as it symbolizes the frustration of a disappointing catch. It often happens that instead of fish, mostly stones appear in the net, and perhaps, along with the fish, the net catches some water snakes, which are very common in the lake. We can imagine Jesus and his followers, carrying their bundles of bread and pickled sardines, appreciating these references to a reality they knew so well.

¶ Christianity and the Symbolism of the Fish

Until the Second Vatican Council, Catholics could be identified by eating fish on Fridays. And it has been a very common religious practice in Catholicism to replace meat with fish in the diet during certain liturgical moments. Is there perhaps in this behavior a certain reverence for the Jewish way of life of Jesus, who as a Jew despised pork and prioritized fish in his diet, even more so since he was a Galilean?

The fish is the oldest Christian symbol. The Greek word for fish, ichthys, is an acrostic for the Greek words that translate “Jesus Christ Son of God the Savior.” The symbol of the fish is a constant in Christian art and literature. The symbol is seen on mosaics in Christian churches, in frescoes, on a painted wall in the catacombs of Rome, on glass, cups, sarcophagi, and monuments throughout the Roman world.

The symbol of the fish was used by persecuted Christians as a code meaning “Christ” to avoid arrest and execution by the Roman authorities. When a picture of a fish appeared outside a Roman home it meant that the Lord’s Supper would be observed that night. Only later did the sign of the cross, scandalous at first, come to replace the fish as the universal symbol signifying the new Christian religion.

¶ References

-

Mendel Nun, Article Fishing in the Sea of Galilee.

-

Elizabeth McNamer, Cast Down Your Nets: Fishing in the Time of Jesus.

-

K.C. Hanson, The Galilean Fishing Economy and the Jesus Tradition, Biblical Theology Bulletin 27 (1997) 99-111. http://www.kchanson.com/ARTICLES/fishing.html

-

Joachim Jeremiah, Jerusalén en tiempos de Jesús (Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1977.