© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

We are so accustomed to calling the Master “Jesus” that we forget that in the language he used in his time, his true name, correctly pronounced, would sound just like this other one: “Yeshua ben Yosef.”

In Hebrew, Yeshua means “Salvation” or “Yahweh saves,” and is a contraction of Yahoshua, which means “The Lord who is Salvation.” However, Jesus has no meaning in Spanish or in other Latin or Anglo-Saxon languages. In this sense, Hebrew names, like the names of other peoples, had a meaning, and very often, this meaning was religious.

There are many Yeshuas throughout the Bible, but these names tend to be confused with different vocalizations to make the name “Jesus” seem unique and original. However, the Master’s name was one of the most common names of that time and in earlier times. Jesus, Jeshua, and Joshua are three ways of using the same name as Jesus.

The name Yeshua appears 29 times in the Law and the Prophets. For example, Yehoshua (Joshua ben Nun) is called Yeshua in Nehemiah (Neh 8:17). Yeshua is the name of the high priest (kohen gadol) during the time of Zerubbabel (Ezra 3:2). It is also the name of a Levite during the reign of Hezekiah (2 Chron 31:15).

To get from “Yeshua” to Jesus, two transliterations occurred. First, when Yeshua was translated into Greek as Iesous. And from Greek, when it was translated into Latin as Iesus. The initial “I” or “Y” sound was eventually forced into Old Spanish, becoming a “J.”

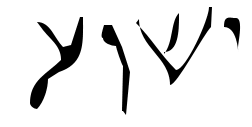

In reality, written Aramaic Yeshua lacks vowels. These are added to form the Aramaic phonemes, but the correct vowel is difficult to determine. Written Aramaic Yeshua consists of the letters yod, shin, final nun, and ayin. These consonants sounded like this: yod like our “y,” shin like a “sh” (long “s”), final nun like a “u,” and ayin like an “h” (a guttural sound that was optional to pronounce, leaving only the chosen vowel, usually “a” or “e,” placed before it). This means that without vowels it would sound like yshuh, but with the addition of the appropriate vowels it would sound like yeshuah or yoshuah or yoshueh. The vowels were not important, so different districts might tend to use one or the other. Perhaps this explains why Peter was recognized by his “Galilean accent” during his denials.

So where does the final “s” in “Jesus” come from? One possible explanation lies in the Greek custom of frequently ending male names with an “s.”

And the surname? How did the different Jesuses of that time distinguish themselves from each other? It was common to use the father’s name as the surname, writing “bar” or “ben” in between, meaning “son of.” For example, Barabbas is actually a nickname meaning “Barabba” (son of his father). In the case of Jesus, his full name would be “Yeshua ben Yosef” (Jesus son of Joseph).

What if there was more than one son and father with the same name? In that case, the paternal genealogy was continued as far as necessary. Jews were fond of boasting about their racial purity by enumerating their ancestors back several dozen generations. This allowed them to prove Jewish legitimacy. Bastards or children born from non-Jewish unions tainted all the descendants for generations and generations, thus leaving them outside the privileges of “true Jews.” The reality, however, was that almost all Jews had some crossbreeding at some point in their ancestry, but everyone covered up these black spots on their family trees by paying large sums to scribes, who falsified all kinds of documents recording official ancestry. This makes it easier to understand why the Gospels offer these strange genealogies of Jesus (Mt 1:1-17, Lk 3:23-38). Their objective is to assure the legitimacy and Jewish purity of Jesus in the face of those who denied his Jewish paternity in order to discredit him.

The Romans, on the other hand, less interested in these genealogical questions, tended to refer to their subjects by their place of origin. For this reason, Pontius Pilate placed a tablet with the name “Jesus of Nazareth” above the cross.

Taking all this into account, I have tried to have Jesus appear named in the story[1] with different names similar to Yeshua depending on the place and the people who spoke with him.

Finally, an image of how the four letters of Yeshua were written in Aramaic. For reading, it’s important to keep in mind that Aramaic and Hebrew, like Arabic, were written from right to left.

¶ External links

¶ References

-

Various authors, Jesús y su tiempo (Jesus and His Times), Reader’s Digest, 1987.

-

Philip R. Davies, George J. Brooke and Phillip R. Callaway, Los rollos del Mar Muerto y su mundo (The Dead Sea Scrolls and Their World), Alianza Editorial, 2002.

¶ Notes

This story is the novel «Jesus of Nazareth», a biography of the Master based on The Urantia Book that is in preparation by the author. ↩︎