© 1995 Ken Glasziou

© 1995 The Brotherhood of Man Library

Many, many moons ago, when I was a young surfie, my friends and I could be found out to sea somewhere, sitting on our surf boards, waiting for the god of the waves to send us a ‘set.’ In surfie parlance, a ‘set’ was a group of big waves that seems to come from nowhere. The god of the waves was called ‘Hughie’ and was one to whom surfies prayed fervently by using the supplication, “Send them up, Hughie.” Further moons later, I learned that the principal cause of a ‘set’ was the same phenomenon that physicists call ‘interference.’ This can happen when the peaks of two waves from different sources coincide, adding themselves together to form one big wave. If, however, the peak of one coincides with the trough of the other, they cancel and the sea becomes flat. Since surfies, in those days, were rarely physicists, sets were considered to be creative acts on the part of deity. Hughie was an Old Testament type of god—wrathful, jealous, and perverse—who exerted his authority by keeping surfies guessing where and when sets would occur.

Physicists who study matter at the level of the atom are also confronted with bizarre wave phenomena. They never seem to know when the particles they study are going to behave as if they are waves or as if they are particles. What they don’t know is that it is Hughie who confuses them. What’s more, Hughie deals harshly with physicists because most of them refuse to acknowledge the legitimate powers of Deity. With his typical perversity, he refuses to let them know all about anything—so that they wind up wondering whether they know anything about everything. This they call indeterminism. For example, Hughie will not let them know the position and speed of an electron at the same moment of time. If they know where it is, they can’t know how fast it is going. And vice versa. They call this Hughie factor, the ‘Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.’ [Unscientifiques may advance to paragraph 1, p. 14]

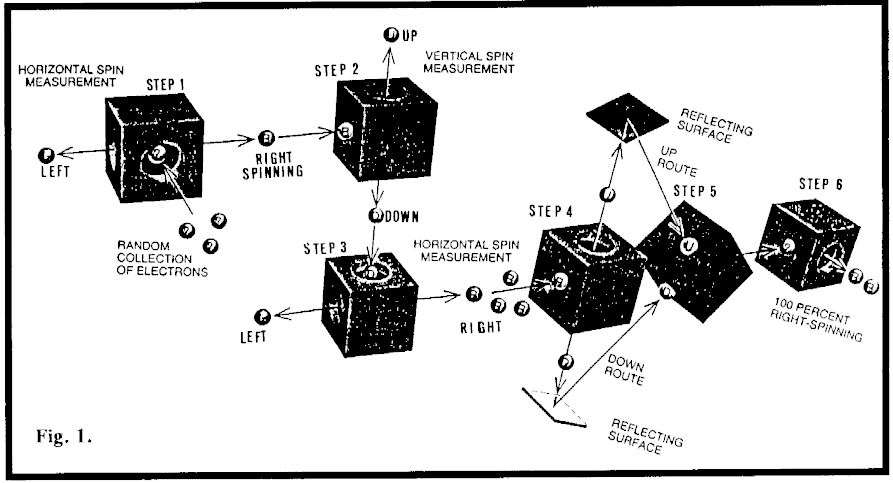

Hughie’s extraordinary perversity with particle physicists is illustrated in Fig. 1. Electrons have spin, there being a vertical and horizontal component. Do not try and take this too far because their kind of spin is like nothing you have experienced up here in reality. To keep it simple, we will say that left electrons spin left, right electrons spin right, up electrons spin up and down electrons spin down.

Physicists have little black boxes that can separate the various components of spin. However, if they separate left spin from right (as in step 1, Fig.1), then put the right spin electrons through a box that separates the up and down part of spin, for reasons only known to Hughie, the left-right spin gets randomized. This shows up in step 3, where the down spinning electrons have been put through a black box that measures left-right spin with the result that some now spin left (50%), and the rest spin right.

By the time this particular experiment was done, particle physicists had come to believe in their own deification. They actually believed that nothing happens anywhere, anytime, except when a particle physicist looks to see what happens. This got them into arguments with normal people like Einstein who said their theory was nutty. A fellow called Schrödinger got into the argument along with his cat. Hypothetically, he put the cat in a box, then devised ways by which it could commit suicide. Schrodinger’s cat was supposed to stay dead and alive (at the same time) until a particle physicist took a look in the box. The argument has continued right up to the present time, even though both the cat and Schrodinger have long since departed due to old age. It seems that particle physicists are averse to opening boxes. It appears also that they are deficient in a sense of smell.

Let’s move to step 4, Fig.1. One of the physicists wanted to know what would happen if they did not open one of their boxes. This was to test the idea that if they don’t know about it, it doesn’t happen. So in step 4, they took all the right spin electrons from step 3 and fed them through an up-down separator (which should also have destroyed the left-right spin). What better way not to know what had happened than to put both streams of the up and down separation back into a mixer box (step 5, Fig.1). They also made certain that nobody took a peek at what was in the mixer. Then they fed the mixture through a left-right spin separator (step 6, Fig.1). (Go to a simplified version of this work.)

Here Hughie decided to get in the act. He reasoned as follows: “These guys took right-spinning electrons so they had that as certain knowledge. Then they put them through their up-down separator so they would have upright and downright electrons. Normally that would randomize the left-right spin. But in this case they have not looked to observe the up and down component. So their certain knowledge is back with a bunch of right spinning electrons. O.K. then, let’s leave it at that.” And that is what Hughie did (step 6, Fig.1). Only right-spinning electrons issued forth.

Puzzling though it may have been, this result appeared to confirm the god-playing propensities of particle physicists. Things only happen when they observe, not otherwise. So Schrodinger’s cat really is dead and alive after all. But some were not satisfied. So they tried another test.

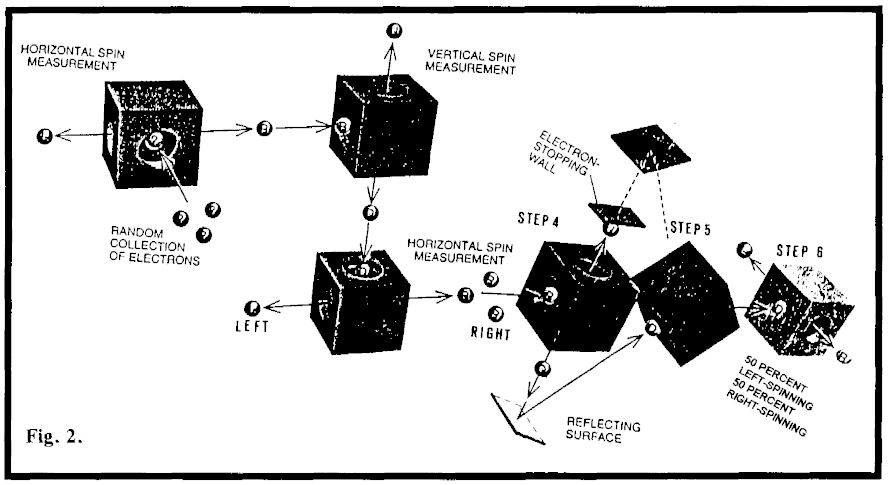

Fig. 2 is identical to Fig.1 up to step 4. One physicist wanted to know what would happen if they confused step 5 by only permitting the down electrons to go through to step 6. So they blocked the ‘up’ path from box 4 (Fig.2).

Hughie reasoned as follows: “Now,” he said, “if these guys made the observation, they would have certain knowledge that the electrons they are playing with have down spin. They want to know if they also still have right spin. That is not in accord with my rules.” He pondered about what he had done in the previous case, couldn’t make up his mind, so flipped a coin, It came out that he would randomize the down spin. So when the physicists ‘observed’ to see what came out of step 6, Fig.2, they found both left- and right-spinning electrons. Would you believe that?

You would think the particle physicists would have had enough by now. But no. One wanted to know what would happen if they sent one of their number off to the moon, along with the electrons from box 6 of both experiments—but before anyone had looked in the boxes to see what had happened. Actually things went wrong at blast off and everything got mangled. So it was left to others to demonstrate the reality of what physicists call ‘non-local effects’ that take place instantaneously even though the two components are separated by up to and including infinite distance. (see the Chiao et al. reference)[unscientifiques resume here]

To explain non-local effects a little better, let’s take a two-particle system with opposite spins such that the spins cancel. If we have twin electrons of this kind, one will have up spin and the other down. But if we change the spin of one, the other changes automatically. Let’s now give one electron to a particle physicist and send him to Mars. We give him a time schedule for observing the spin of his electron. We give the twin electron to an ‘at home’ particle physicist with the same time schedule and a list of spin states to give to his electron. Later, when we compare the results, we find the electrons are always in opposite states. Question: How did the Mars electron know when to flip? Instantaneously? That is what is meant by non-local effects.

¶ A vacuum full of goodies?

Quantum theory has lots of other funny quirks that normal folk would not believe. The quantum vacuum is one of these. It is a vacuum that is not empty but is a soup filled with a multitude of virtual particles having temporary residence. They come into being as non-identical twins, particle and anti-particle, exist momentarily, then annihilate one another. Quantum theory allows them to do this by borrowing sufficient energy from the vacuum to sustain their fleeting existence. They pay it back when they annihilate. Willis Lamb received the Nobel prize for first presenting evidence for the reality of vacuum effects. A Dutchman, Hendrik Casimir, clinched the argument by a totally different means, so much so, it is difficult not to believe in the quantum vacuum and its virtual particles.

Einstein and other realists held out against quantum indeterminism for a long, long time. Einstein felt that God would not play dice with the world—and died protesting (Einstein, that is). The experiments to demonstrate non-locality came about to test a ‘thought’ experiment proposed by Einstein and his mates in 1935. It is known as the E-P-R experiment and was an untestable hypothesis until an Irish physicist, John Bell, invented Bell’s theorem and came up with a way of testing it. This has now been done to the satisfaction of all. Non-local effects occur instantaneously even at infinite distance when no message travelling at the speed of light could possibly allow direct communication. To date, nobody has found a way to actually send a message at faster than light speeds, but there can be no doubt that the particles ‘know’ what they must do.

¶ Some flies in the soup—Bohm and The Urantia Book

At least one quantum physicist, David Bohm, refused to accept the deification of quantum observers. Bohm maintained the universe and all therein (matter-wise) is determinate. Ordinary quantum physicists propose a wave function that contains all the possibilities to describe a system. They then portion out probabilities of occurrence to each possibility. They claim that when an observer looks to see what has happened, one of these possibilities suddenly becomes the real thing and all the others collapse to nothingness. Thus Schrodinger’s cat remains dead and alive in a superposition of states until a physicist lifts the lid and announces its fate. At the sub-atomic level, thousands of observations confirm that this concept is an apparently valid description of reality. By training, quantum physicists (and many other scientists) are conditioned to believe that the only truth is observable truth. The role of the observer is sacrosanct. Nothing happens until he, she, or it, observes. This is often called the Copenhagen interpretation—for which Neils Bohr gets the blame.

The Copenhagen interpretation proposes at least three curious ‘facts’ (?) about the physical world. First, pure chance governs the innermost workings of nature. Second, although material objects always occupy space, situations exist in which they occupy no particular region of space. Third, the observer and his instruments are afforded a privileged status outside of the laws that govern the things being observed. In a recent review, David Albert states: “although the Copenhagen interpretation probably remains the guiding dogma of the average working physicist, serious students of the foundations of quantum mechanics rarely defend the standard formulation any more.”

In 1952, David Bohm published an alternative interpretation, later given polish by the Irish physicist, John Bell. The new notions of Bohm’s interpretation can be summed up in terms of the concept that the wave-function of quantum theory determines a quantum potential representing active information which gives form to the motion of particles that, however, move under their own energy. There are numerous bits and pieces of Bohm’s theories that have parallel expression in The Urantia Book.

¶ R.I.P. Schrodinger’s cat?

Whereas Bohr’s quantum theory is indeterminate, Bohm’s is fully deterministic. Bohm also denies that there are any such things as superpositions (i.e. dead and alive cats). The Urantia Book agrees: “Aside from the presence of the Unqualified Absolute, electrical and chemical reactions are predictable.” (UB 65:6.8)

¶ Einstein was right? Photons are particles?

Bohm’s theory says light is both particle and wave at the same time, until observed. Bohm and The Urantia Book treat light as particulate. Discussing his theories, Bohm says: “. . . considering a single particle of matter (e.g, an electron), according to the quantum theory such a particle shows wave-like properties as well as particle-like properties. I propose to explain this by assuming that while the electron is a particle, it is always accompanied by a new kind of wave field determined by Schrodinger’s equation. The electron must be understood in terms of both the particle and the field which always accompanies the particle. . . the Schrodinger equation, expressed in terms of this model. . . needs an additional new kind of force derivable from what I call the quantum potential. . . which does not depend on the intensity of the wave but only on the form. . . We can regard the quantum potential as containing active information, potentially active everywhere, but actually active only where and when there is a particle. (An analogy would be radio waves directing the flight path of an aeroplane on automatic pilot.)”

“We may illustrate what this means by considering what happens to a statistical distribution of electrons that pass through a system of two slits and are detected on a screen. . . Suppose we consider a specified particle so located that it goes through one of the slits. Afterwards it will follow a complicated path so that it is significantly affected by a quantum potential determined by the interference of waves from both slits. . . In this way, we understand that the path of each particle depends very much on whether one slit is open, or both are open. This is the proposed explanation of how the electron can behave in some ways like a particle and in others, like a wave. . . depending strongly on the information in the form of a wave that reflects the whole environment. Nevertheless, it ultimately arrives at a particular point on the screen, thus demonstrating the particle nature of the electron. Yet, in a random statistical distribution of electrons with the same Schrodinger wave, all these particles bunch to produce a fringe-like distribution on the screen (interference pattern). The field of information in the Schrodinger wave is thus reflected in the statistical distribution, and in this way we understand how the dependence of each particle in this field of information brings about the wave-like behavior of a statistical distribution of such particles.”

¶ Do photons run on autopilot?

Photons of light would, of course, behave in the same way as the electrons described above. Compare Bohm’s idea (only the wave went through both slits) to one in The Urantia Book. “Energy, whether as light or in other forms, in its flight through space moves straight forward. The actual particles of material existence traverse space like a fusillade. . . Solar energy may seem to be propelled in waves, but that is due to the action of coexistent and diverse influences. A given form of organized energy does not proceed in waves but in direct lines, The presence of a second or a third form of force-energy (Bohm’s quantum potential?) may cause the stream under observation to appear to travel in wavy formation, just as, in a blinding rainstorm accompanied by a heavy wind, the water sometimes appears to fall in sheets or descend in waves.” (UB 41:5.7)

¶ Electrons have a sub-structure?

Bohm believes that electrons must have a sub-structure. Discussing his explanation for apparent particle-wave duality, he says, “This model implies that an electron is not a simple billiard-ball entity, but that it may have an inner complexity comparable to that of a radio set or a vessel guided by an automatic pilot. . . Current theoretical notions suggest that an electron cannot be larger than something in the order of 1/1016 cm. . . Between this and the Planck length of 1/1033 cm, there is a range of scales as great as that between every-day dimensions and the presumed size of the electron. Thus, there is ample room for the possibility of the requisite structural complexity.” The Urantia Book tells us, “Mutual attraction holds one hundred ultimatons together in the constitution of the electron; and there are never more nor less than one hundred ultimatons in a typical electron.” (UB 42:6.5)

So did Bohm get his revolutionary ideas from The Urantia Book? Not likely, for they were first published in 1952. So are they the mental meanderings of just another nut case? Again not likely for speaking about them, John Bell (1987) said, “Bohm’s 1952 papers on quantum mechanics were for me, a revelation. I have always felt, since, that people who have not grasped the ideas of those papers (and unfortunately they remain the majority) are handicapped in any discussion of the meaning of quantum mechanics.” And in his review, David Albert (1994) states, “Bohm’s theory accounts for all the unfathomable-looking behaviors of electrons every bit as well as the standard interpretation does. Moreover, and this point is important, it is free of any of the metaphysical perplexities associated with quantum-mechanical superposition.”

As a matter for speculation, where do the Absolutes fit in the scheme of things? Perhaps the quantum vacuum is the domain of the Unqualified Absolute. The virtual particles that flit in and out of the vacuum could be in the domain of the Universal Absolute. But when potentials become actuals, it would appear that we move into the domain of the Deity Absolute (also called the Qualified Absolute).

Bohm’s wave function guides particle behavior. So where does Hughie, the god of the waves and all surfies, hold court? The Urantia Book provides a clue, “The interelectronic space of an atom is not empty. Throughout an atom this interelectronic space is activated by wavelike manifestations which are perfectly synchronized with electronic velocity and ultimatonic revolutions. This force is not wholly dominated by your recognized laws of positive and negative attraction; its behavior is therefore sometimes unpredictable. This unnamed influence seems to be a space-force reaction of the Unqualified Absolute.” (UB 42:8.2) Unpredictable! Out of this world! That’s Hughie!!!

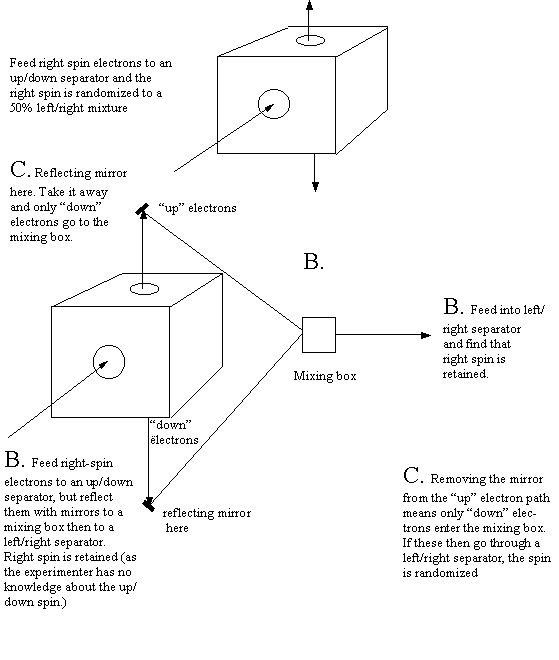

In “B,” we take right spin electrons, feed them through an up/down separator, but reflect the streams back into a mixing box thus losing any information on up/down spin. If the electrons from the mixing box are then passed through a left/right separator they are found to be 100% right spin.

However blocking the path of the “up” stream electrons so they do not enter the mixing box, gives only “down” electrons in the mixing box. But then passing these electrons from the box through our left/right separator gives us a 50% mix of left/right spin electrons. It appears that we are not permitted to have knowledge of both kinds of spin at the same time.

¶ References

- Albert, David Z. (1994) “Bohm’s Alternative to Quantum Mechanics.” Scientific American 270 (#5).

- Bell, J.S. (1987) in “Quantum Implications: Essays in honour of David Bohm.” (Ed. Hiley and Peat) (Routledge, London)

- Chiao, R.Y., Kwiat, P.G., and Steinberg, A.M. (1993) “Faster than Light.” Scientific American 269 (#2).

- Bohm, D. (1952) Phys. Rev. 85, 166

- Bohm, D., and Hiley, B. (1987) Physics Report 144, 323.

- Bohm, D. and Peat, D. (1987). “Science, Order, and Creativity.” (Bantam Books, New York,)

- Pylkkanen, P. (1989) “The Search for Meaning.” (Aquarian Press, Thorsons Publishing Group, Wellingborough, England)