© 2004 Ken Glasziou

© 2004 The Brotherhood of Man Library

¶ Hypotheses on the possible origins of the Urantia Paper’s statement on star collapse

In the early 1930’s, the idea that supernova explosions could occur and result in the formation of neutron stars was extensively publicized by Fritz Zwicky of the California Institute of Technology (Caltec) who worked in Professor Millikan’s Dept. For a period during the mid-thirties, Zwicky was also at the University of Chicago. Dr. Sadler is said to have known Millikan. So alternative possibilities for the origin of The Urantia Book quote above could be:

-

The revelators followed their mandate and used a human source of information about supernovae, possibly Zwicky.

-

Dr Sadler had learned about the tiny particles devoid of electric potential from either Zwicky, Millikan, or some other knowledgeable person and incorporated it into The Urantia Book.

-

It is information supplied to fill missing gaps in otherwise earned knowledge as permitted in the mandate. (UB 101:4.9)

Zwicky had the reputation of being a brilliant scientist but given to much wild speculation, some of which turned out to be correct. A paper published by Zwicky and Baade in 1934 proposed that neutron stars would be formed in stellar collapse and that 10% of the mass would be lost in the process (Phys. Reviews. Vol. 45)

In “Black Holes and Time Warps. Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy” (Picador, London, 1994), a book that covers the work and thought of this period in detail, K. S . Thorne, Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltec, writes: In the early 1930’s, Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade joined forces to study novae, stars that suddenly flare up and shine 10,000 times more brightly than before. Baade was aware of tentative evidence that, besides ordinary novae, there existed superluminous novae. These were roughly of the same brightness but since they were thought to occur in nebulae far out beyond our Milky Way, they must signal events of extraordinary magnitude. Baade collected data on six such novae that had occurred during the current century.

As Baade and Zwicky struggled to understand supernovae, James Chadwick, in 1932, reported the discovery of the neutron. This was just what Zwicky required to calculate that if a star could be made to implode until it reached the density of the atomic nucleus, it might transform into a gas of neutrons, reduce its radius to a shrunken core, and, in the process, lose about 10 % of its mass. The energy equivalent of the mass loss would then supply the explosive force to power a supernova.

¶ Zwicky believed cosmic rays accounted for the supernova mass-energy loss

Information, extracted from Thorne’s book[1], indicates that Zwicky knew nothing about the possible role of “little neutral particles” in the implosion of a neutron star, but rather that he attributed the entire mass-energy loss to cosmic rays. So, if not from Zwicky, what then is the human origin of The Urantia Book’s statement that the neutrinos escaping from its interior bring about the collapse of the imploding star? (Current estimates attribute about 99% of the energy of a supernova explosion to being carried off by the neutrinos).

In his book[1:1], Thorne further states: “astronomers in the 1930’s responded enthusiastically to the Baade-Zwicky concept of a supernova, but treated Zwicky’s neutron star and cosmic ray ideas with disdain. . . In fact it is clear to me from a detailed study of Zwicky’s writings of the era that he did not understand the laws of physics well enough to be able to substantiate his ideas.”

This opinion was also held by Robert Oppenheimer who published a set of papers with collaborators Volkoff, Snyder, and Tolman, on Russian physicist Lev Landau’s ideas about stellar energy originating from a neutron core at the heart of a star.

¶ Einstein and Eddington opposed neutron star concept

These Oppenheimer papers concluding that either neutron stars or black holes could be the outcome of massive star implosion were about as far as physicists could go at that time. However, the most prominent physicist of the time, Albert Einstein, and the doyen of astronomers, Sir Arthur Eddington, both vigorously opposed the concepts involved in stellar collapse beyond the white dwarf stage. Thus the subject appears to have been put on hold coincident with the outbreak of war in 1939.

During the 1940’s, virtually all capable physicists were occupied with tasks relating to the war effort. Apparently this was not so for Russian-born astronomer-physicist, George Gamow, a professor at Leningrad who had taken up a position at George Washington University in 1934. Gamow conceived the beginning of the Hubble expanding universe as a thermonuclear fireball in which the original stuff of creation was a dense gas of protons, neutrons, electrons, and gamma radiation which transmuted by a chain of nuclear reactions into the variety of elements that make up the world of today. Referring to this work, Overbye[2] writes: “In the forties, Gamow and a group of collaborators wrote a series of papers spelling out the details of thermonucleogenesis. Unfortunately their scheme didn’t work. Some atomic nuclei were so unstable that they fell apart before they could fuse again into something heavier, thus breaking the element building chain. Gamow’s team disbanded in the late 40’s, its work ignored and disdained.”

Among this work was a paper by Gamow and Schoenfeld that included a suggestion that energy loss from aging stars could be mediated by an efflux of neutrinos. This proposal appears to have been overlooked or ignored until the 1960’s. However it appears to be the direct source for UB 41:8.3 quotation from the Urantia Papers and bears similarities to the use of the direct quotations from the Swann book (see p.10) by the Papers’ authors in that the authors selectively use that which is right and ignore that which is wrong. In their conclusions, Gamow and Schoenfeld drew attention to the fact that, “the neutrinos are still considered as highly hypothetical particles because of the failure of all efforts to detect them,” also noting that “the dynamics of the collapse represents very serious mathematical difficulties.” And in other papers from this Gamow group, the neutron star idea is ignored in favor of large stars gradually shedding their excess mass and retiring gracefully as white dwarfs.

¶ Conservation of energy law under fire

As time went by, the need for the neutrino grew, firstly to save the law of conservation of energy, but also laws of conservation of momentum, angular momentum (spin), and lepton number. As knowledge of what it ought to be like grew, plus the knowledge accruing from the intense efforts to produce the atom bomb, possible means of detecting this particle began to emerge. In 1953, experiments were begun by a team led by C.L. Cowan and F. Reines. Fission reactors were now in existence in which the breakdown of uranium yielded free neutrons that, outside of the atomic nucleus, were unstable and broke down via beta decay to yield a proton, an electron, and, if it existed, the missing particle.

¶ Detection of the elusive neutrino

The Cowan and Reines team devised an elaborate scheme to detect the antineutrinos from a reactor. By 1956 their system was detecting 70 such events per day, unequivocally ascribable to antineutrinos. It now remained to prove that this particle was not its own antiparticle, as is the case with the photon. This was done by R.R. Davis in 1956 using a detection system designed specifically for what the properties of the neutrino should be and testing it with an antineutrino source from a fission reactor.

¶ Search resumed

According to eminent Russian astrophysicist, Igor Novikov, no searches in earnest for neutron stars or black holes were attempted by astronomers before the 1960’s. He says, “It was tacitly assumed that these objects were far too eccentric and most probably were the fruits of theorists’ wishful thinking. . . at any rate, if they existed, then they could not be detected.[2:1]”

The subject of the fate of imploding stars re-opened with vigor when both Robert Oppenheimer and John Wheeler, two of the really great names of physics, attended a conference in Brussels in 1958. Oppenheimer believed that his 1939 papers said all that needed to be said about such implosions. Wheeler disagreed, wanting to know what went on beyond the well-established laws of physics.

When Oppenheimer and Snyder did their work in 1939, it had been hopeless to compute the details of the implosion. In the meantime, nuclear weapons design had provided the necessary tools because, to design a bomb, nuclear reactions, pressure effects, shock waves, heat, radiation, and mass ejection had to be taken into account. Wheeler realized that his team had only to rewrite their computer programs so as to simulate implosion rather than explosion. However his hydrogen bomb team had been disbanded and it fell to Stirling Colgate at Livermore, in collaboration with Richard White and Michael May, to do these simulations. Wheeler learned of the results and was largely responsible for generating the enthusiasm to follow this line of research. The term ‘black hole’ was coined by Wheeler.

The theoretical basis for supernova explosions is said to have been laid by E. M. Burbidge, G.R. Burbidge, W. A. Fowler, and Fred Hoyle in a 1957 paper[3]. However, even in Hoyle and Narlikar’s text book, “The Physics-Astronomy Frontier” (1980), no consideration is given to a role for neutrinos in the explosive conduction of energy away from the core of a supernova. In their 1957 paper, Hoyle and his co-workers proposed that when the temperature of an aging massive star rises to about 7 billion degrees K, iron is rapidly converted into helium by a nuclear process that absorbs energy. In meeting the sudden demand for this energy, the core cools rapidly and shrinks catastrophically, implodes in seconds, and the outer envelope crashes into it. As the lighter elements are heated by the implosion they burn so rapidly that the envelope is blasted into space. So, two years after the first publication of The Urantia Book, the most eminent authorities in the field of star evolution make no reference to the “vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential” that the book says escape from the star interior to bring about its collapse. Instead they invoke the conversion of iron to helium, an energy consuming process now thought not to be of significance.

Following on from the forgotten 1940’s paper of Gamow and Schoenfeld paper, the next suggestion that neutrinos may have a role in supernovae came from Ph.D. student, Hong-Yee Chiu, working under Philip Morrison. Chiu proposed that towards the end of the life of a massive star, the core would reach temperatures of about 3 billion degrees at which electron-positron pairs would be formed and a tiny fraction of these would give rise to neutrino-antineutrino pairs. Chiu speculated that X-rays would be given off by the star for about 1000 years and that the temperature would ultimately reach about 6 billion degrees when an iron core would form at the central region of the star. The flux of neutron-antineutrino pairs would then be sufficiently great to carry off the explosive energy of the star in a single day. The 1000-year period predicted by Chiu for X-ray emission was reduced to about one year by later workers. Chiu’s proposals appear to have been first published in a Ph. D. thesis submitted at Cornell University in 1959. Scattered references to it are made by Philip Morrison[4] and by Isaac Asimov[5].

¶ No neutral current, no supernova

Dennis Overbye, in his book “Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos[6]” records that, for supernovae, almost all the energy of the inward free fall comes out in the form of neutrinos. The success of this scenario (as proposed by Chiu) depends on a feature of the weak interaction called the neutral currents. Without this, the neutrinos do not supply enough ‘oomph’ and theorists had no good explanation for how stars explode. In actuality the existence of the neutral current for the weak interaction was not demonstrated until the mid 1970’s.

A 1985 paper (Scientific American) by Bethe and Brown entitled “How a Supernova Explodes” showed that understanding of the important role of the neutrinos was well advanced by that time. These authors attribute this understanding to the computer simulations of W. David Arnett of the University of Chicago and Thomas Weaver and Stanford Woosley of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

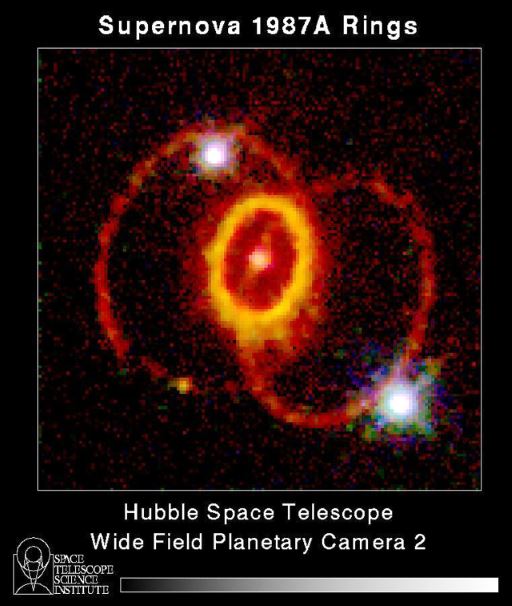

The opportunity to confirm the release of the neutrinos postulated to accompany the spectacular death of a giant star came in 1987 when a supernova explosion, visible to the naked eye, occurred in the Clouds of Magellan that neighbors our Milky Way galaxy. Calculations indicated that this supernova, dubbed SN1987A, should give rise to a neutrino burst at a density of 50 billion per square centimeter when it finally reached the earth, even though expanding as a spherical ‘surface’ originating at a distance 170,000 light years away.

This neutrino burst was observed in the huge neutrino detectors at Kamiokande in Japan and at Fairport, Ohio, in the USA. lasting for a period of just 12 seconds, and confirming the computer simulations that indicated they should diffuse through the dense core relatively slowly. From the average energy and the number of ‘hits’ by the neutrinos in the detectors, it was possible to estimate that the energy released by SN1987 amounted to 2-3 x 1053 ergs.

This is equal to the calculated gravitational binding energy that would be released by the collapse of a core of about 1.5 solar masses to a neutron star. Thus SN1987A provided a remarkable confirmation of the general picture of neutron star formation developed over the previous fifty years.

Presently (2003) it is believed that when the core of a collapsing star implodes with sufficient violence to form a mass of ‘hot’ neutrons at a temperature and pressure exceeding 10 billion degrees and 100 trillion (1014) g/cm3, huge numbers of neutrinos are formed that deposit a shock wave of energy into the envelope–which is blasted away in a supernova explosion. And thus is the Urantia Papers’ assertion fulfilled:

“In large suns . . . when hydrogen is exhausted and gravity contraction ensures, and such a body is not sufficiently opaque to retain the internal pressure of support for the outer gas regions, then a sudden collapse occurs. The gravity-electric changes give origin to vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential, and such particles readily escape from the solar interior thus bringing about the collapse of a gigantic sun within a few days.” (UB 41:8.3)

¶ Who dunit? Paring away the alternatives

Referring to our three alternatives to explain how the reference to the role of the tiny uncharged particles in supernova explosions got to be in the Urantia Papers, our investigation showed that Zwicky is unlikely to have been the source as he firmly believed X-rays, not neutrinos, accounted for the postulated 10% mass loss during the death of the star.

Remembering that neutron stars were not demonstrated to exist until 1967, that some of the biggest names in physics and astronomy were totally opposed to the concept of collapsing stars (Einstein, Eddington), and that, well into the 1960’s, the majority of astronomers (including Gamow) assumed that massive stars shed their bulk piecemeal prior to retiring respectably as white dwarfs, a process for which neutrino loss is unnecessary, it appears that it would have been a preposterous notion to attempt to support the reality of a revelation by means of speculation about neutron star at any time prior to the 1960’s.

If, however, it is assumed that, on what would have needed to be the expert advice of a knowledgeable but reckless astrophysicist, Dr Sadler wrote the page 464 material into the Urantia papers subsequent to the concepts on neutrinos appearing in the Gamow et al. publications of the 1940’s, then it becomes necessary to ask why was it not removed when that work lost any credibility.

That appears to leave the revelators themselves as the major (only?) suspects.

¶ External links

¶ References

Thorne, K.S. (1994) “Black holes and Time Warps: Einstein 's Outrageous Legacy” (Picador, London) ↩︎ ↩︎

Novikov, I. (1990) “Black Holes and the Universe” (Cambridge University Press) ↩︎ ↩︎

Burbidge, E.M., G.R. Burbidge, W.A. Fowler, & F. Hoyle. (1957) ↩︎

Morrison, Philip, (1962) Scientific American 207 (2) 90. ↩︎

Asimov, Isaac, (1966) “The Neutrino” (Dobson Books Ltd., London) ↩︎

Overbye, Dennis (1991) “Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos.” (HarperCollins) ↩︎