© 2001 Ken Glasziou

© 2001 The Brotherhood of Man Library

| On divine truth | Volume 8 - No. 5 — Index | Geophysics—further prophecies: Continental Drift and Age of the Solar System |

¶ Introduction

This article aspires to demonstrate that there is truly prophetic material of a scientific nature in the Urantia Papers (received 1935) that cannot be fobbed off as lucky guess. Supposedly the authors of these Papers were extra-terrestrials. If they have demonstrated they had knowledge unavailable to us earthlings, perhaps they were!! Herein, you are introduced to samples of the prophetic science. However the real significance of these Papers is in their “contemplation of the spiritual realities and universe values of eternal meanings”–which is quite independent of their science content and the status of their authors.

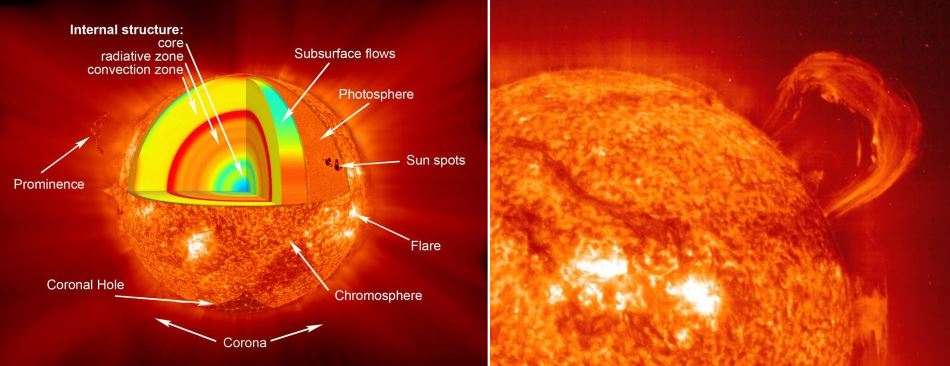

These Papers also contain error, most of which is in accord with having being provided purely as a framework in which to think about the cosmology of creation. (Paper 115, Section 1) But some of the errors are difficult to place in that category. For example the Papers give the surface temperature of the sun as a little less than 6000 degrees F. But current measurements show the photosphere as having the lowest temperature at about 10,800 F. The chromosphere, at 18,000 F, is what many consider to be the surface. From there, the corona temperature rapidly increases up into the millions of degrees. And the Papers give the core as at 35,000 F whereas modern science puts it at 27,000 F.

Remarkably, the Papers provided correct information for events such as the beginnings of the solar system at 4.5 billion years ago, continental drift beginning 750 million years ago, radii of the electron and proton, etc., long before science could confirm them–but made a less than remarkable job of explaining the origin of our earth-moon system and the oceans of the earth.

The purpose of this and the following article is to gain some understanding of why it is so.

¶ Particle physics–two remarkable prophecies: The radii of the electron and proton

In a textbook published at an American university in 1934 entitled, “The Architecture of the Universe,” physicist W.F.G. Swann wrote: “The mass of the electron is so small that if you should magnify all masses so that the electron attains a mass of one tenth of an ounce, that one tenth of an ounce would, on the same scale of magnification, become as heavy as the earth.”

The words of Swann were reproduced in Paper 42, Section 6 but with the comparison obviously deliberately changed from mass to volume. It reads:

“If the mass of matter should be magnified until that of an electron equaled one tenth of an ounce, then were size to be proportionately magnified, the volume of such an electron would become as large as that of the earth.” (UB 42:6.8)

Taking the rest mass of the electron at 9.1 x 10-28 g, 0.1 ounce as 2.8 g, the radius of the earth as 6.4 x 106 m and putting k as the magnification constant, then:

k x 9.1 x 10-28 = 2.8 (1), and so

k = 3.1 x 10-27 (2)

As the radius of the electron (Re) x k is said to be equal to the radius of the earth, we have:

Re x k = 6.4 x 106 (3)

And substituting for k in (3), we get the electron radius:

Re = 2 x 10-21 m (4)

At the time of receipt of the Urantia Papers and up until the 1990’s this made no sense. Many physicists treated the electron as a dimensionless point so at best its radius would be half the Planck length of 10-35 m. Others, by a process of circuitous reasoning, assigned it a radius of 5 x 10-15 m.

The statement remained nonsensical until the 1990’s when Nobel prize winner, Hans Dehmelt, found a way to confine a single electron to a trap semi-permanently. This achievement allowed actual measurements to be made that assigned the radius of the electron to fall into the range of 10-19 m to 10-22 m.

This new estimate was noticed by physicist Stefan Talqvist, a Urantia Book student who had previously checked the calculation using the Urantia Paper’s version of Swann’s earlier work. A few years later at Dehmelt’s laboratory, refining of their techniques allowed them to settle for the electron radius being in the order of 10-22 m, so even closer to the 2 x 10-21 that is calculated for the Urantia Papers modified version of Swann’s comparison.

What are the chances that these figures are coincidental, that the correspondence came about through accident or guesswork alone? Let’s be conservative and consider only the order of magnitude. The possible range could extend to the Planck length of 10-35 m, so approximately a 25-30 fold range, with the chances of a close guess roughly at one in twenty five. But there was a second part to Swann’s comparison that went:

“Then we have the proton–the fundamental unit of positive charge–a thing 1800 times as heavy as the electron, but 1800 times smaller in size, so that if you should magnify it to the size of a pin’s head, that pin’s head would, on the same scale of magnification, attain a diameter equal to that of the earth’s orbit around the sun.”

[Note: Swann’s estimate of the size of the proton as 1800 times smaller than the electron came from using r = e2/mc2, where e is the charge of the electron. The charge to mass ratio for the electron was known accurately by the early 1900 period. The charge was determined by Millikan in 1909. Its mass was then determined as 9.11 x 10-28 g.]

The Urantia Paper’s author did not use this equation, changing the comparison to:

“If the volume of a proton–eighteen hundred times as heavy as an electron—should be magnified to the size of the head of a pin, then, in comparison, a pin’s head would attain a diameter equal to that of the earth’s orbit around the sun.” (UB 42:6.8)

You can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it.

G.K. Chesterton

To treat your facts with imagination is one thing, to imagine your facts is another,

John Burroughs

Stefan Talqvist was again responsible for doing the calculations and drawing attention to this remarkable piece of prophetic material in the Papers.

Taking the radius of the Earth’s orbital around the sun as 1.5 x 1014 mm and the radius of the pinhead as 1 mm, the magnification factor (k) is obtained by dividing the Earth’s orbital radius by the pinhead radius, so 1.5 x 1014 / 1.0, which is 1.5 x 1014 (k)

The radius of the proton times the magnification factor (k) is equal to the radius of the pinhead, hence:

Proton radius x 1.5 x 1014 = pinhead radius (1.0 mm), so

Proton radius = 1.0 /1.5 x 1014, which is 6.7 x 10-15 mm, or 6.7 x 10-18m.

The classical radius for the proton was given as 0.85 x 10-15m so again the Urantia Paper’s comparison looked to be nonsensical.

In later years it was realized that the proton consisted of three subunits called quarks and this component accounts for only about 50% of the proton’s measured momentum, the remainder being accounted for by virtual particles that flip in and out from the vacuum. The current estimate of what is now termed the Bohr radius, a measurement of the ‘real’ part of the proton was given in Physics Today of November 1993, as 7.7 x 10-18 m.–the same order of magnitude as that for the Urantia Paper’s estimate.

Again using order of magnitude to compare the figures, the range for the proton may be about three to five orders less. If we set round figures for both, 25 for the electron and 20 for the proton, then the chances for guessing both comes out at one chance in about 500. Which also means that there are 499 ways to be wrong and illustrates that being right is so much more difficult that being wrong. Even at the 0.05 probability level, there are nineteen ways to be wrong for every one of being right.

When we take into consideration that Swann’s details were deliberately modified in both estimates in order that they produce these results, it becomes impossible to support the notion that this was simply a lucky guess. Any rational interpretation must surely allow that it is a most remarkable prophesy of what our concepts for these parameters would be as we turn the corner into the twenty-first century.

¶ Astrophysics—more prophecies: Neutrinos, Neutron Stars, and Black Holes

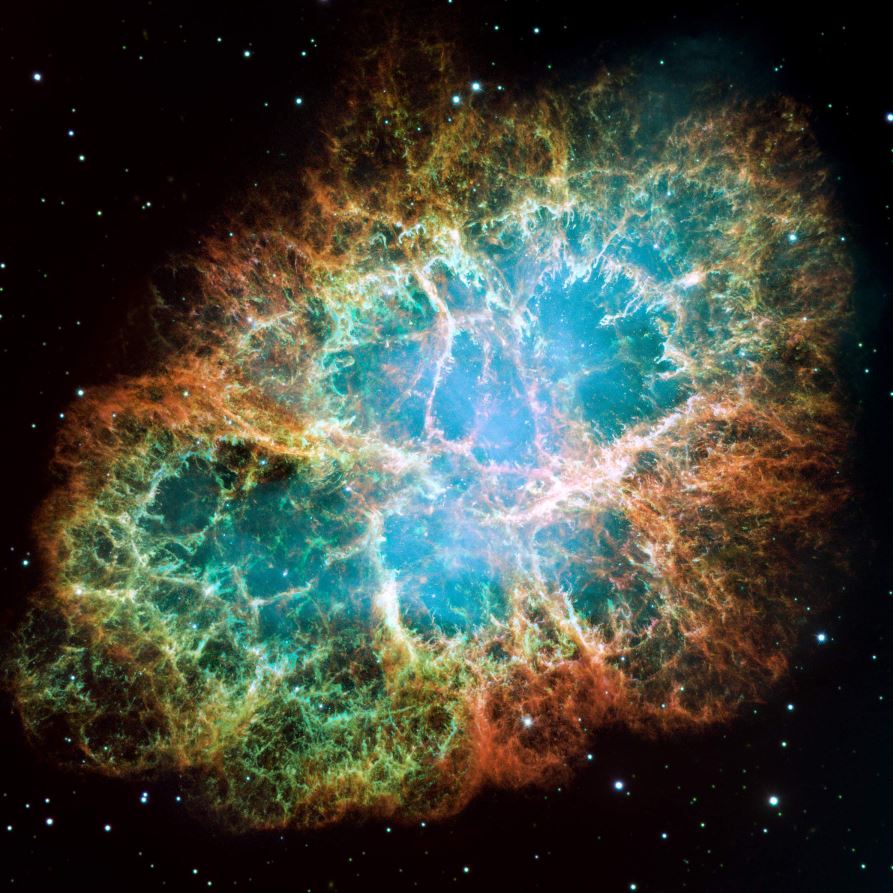

“In large suns when hydrogen is exhausted and gravity contraction ensues, if such a body is not sufficiently opaque to retain the internal pressure of support for the outer gas regions, then a sudden collapse occurs. The gravity-electric changes give origin to vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential, and such particles readily escape from the solar interior, thus bringing about the collapse of a gigantic sun within a few days.” (Paper 41, Section 9)

At the time of receipt of the Urantia Papers (1935), it was generally believed that the destiny for large stars well in excess of the size of our sun was to blow off their outer layers by a series of explosions until they could retire in comfort as a white dwarf, the same destiny as expected for our own sun. Names for neutron stars, neutrinos, and black holes had not even been invented and all were, at best, figments of the imagination.

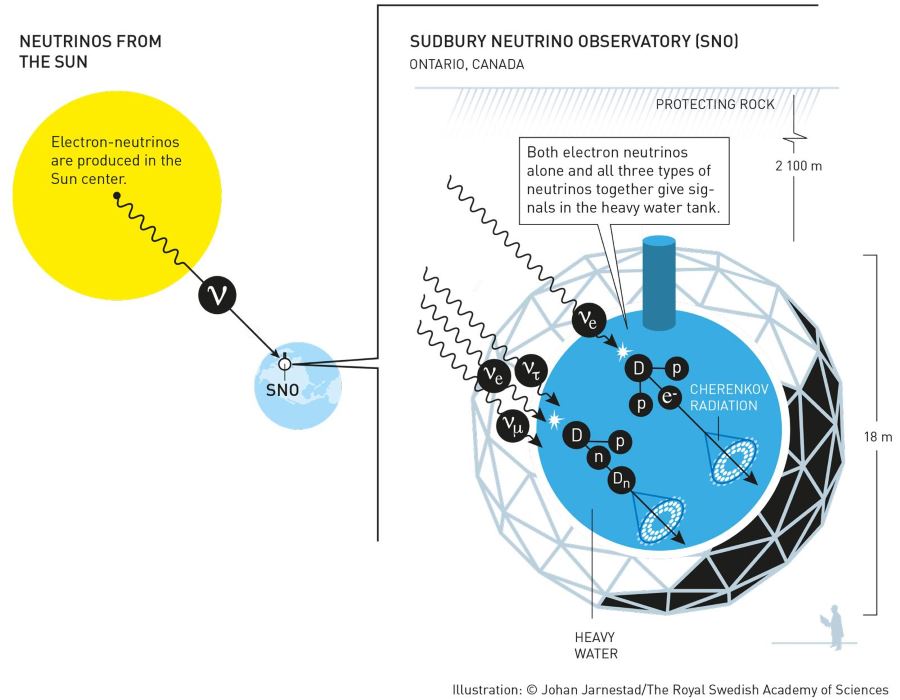

The concept of a particle with no properties, hence one that would be impossible to ever detect, was proposed by leading physicist, Wolfgang Pauli, as a result of the inability of experimentalists to account for mass-energy that disappeared during radioactive beta decay. During subsequent years this became a serious enough problem so that in 1953, Cowan and Reines began experiments using a fission reactor to try to detect Pauli’s undetectable particle. Success did not come until 1956, when R.R. Davis was able to detect its antiparticle, what is now called the anti-neutrino.

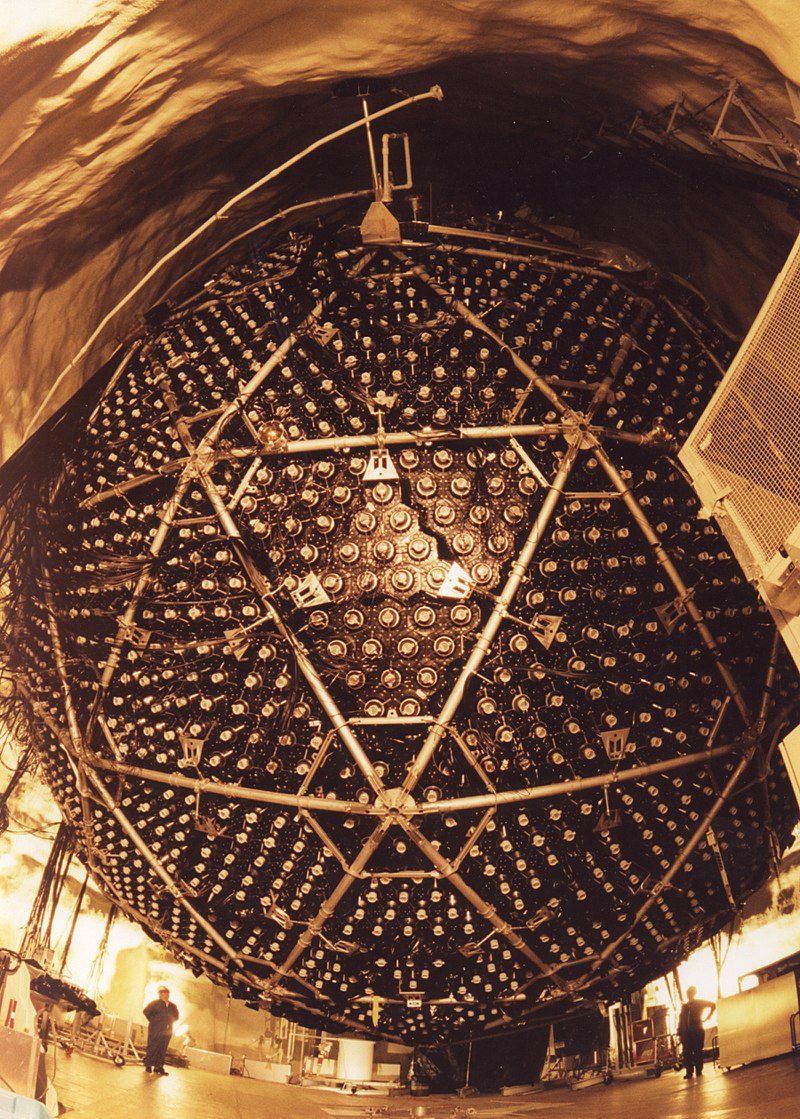

This discovery ensured that neutrinos did actually exist. However the neutrino itself was not finally detected until 1965 when they were identified coming from the sun using huge perchloroethylene tanks buried far underground.[1] The neutrino is now recognized as the particle referred to as “vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential” that are capable of escaping from the interior of an exhausted large star undergoing gravitational collapse.

That the above description, as given in the Urantia Papers, is an accurate description of what is now called a supernova, is indisputable. Yet the theoretical basis for such explosions was not laid until 1957[2], but even then the neutrino was not implicated as the means by which the energy of the explosion could escape so readily. This is perhaps more easilycomprehended when we realize that light energy generated in the interior of such stars may take a million years or more to reach its surface. The neutrino, because of its inertness, makes that very same journey in a few seconds.

The concept of a supernova was first mooted by Zwicky and Baade in 1933 as an explanation for about half a dozen unexplained gigantic explosions that had been observed by astronomers. However the idea that they could arise from the collapse of large stars had no theoretical back-up. Zwicky calculated that about ten percent of the mass of the star might be lost this way. In his book on black holes[3], physicist K.S. Thorne states that Zwicky knew nothing about the possible role of “little neutral particles” being released in the implosion of a large star. Instead he had attributed the entire mass-energy loss to cosmic rays. Zwicky’s idea that a supernova-type collapse could occur was ridiculed by many and was also strongly opposed in 1939 by the most prominent physicist of the time, Albert Einstein, as well as the most prominent astronomer, Sir Arthur Eddington.

According to eminent Russian astrophysicist, Igor Novikov, no searches in earnest for neutron stars or black holes were attempted by astronomers before the 1960’s. He says, “It was tacitly assumed that these objects were far too eccentric and most probably were the fruits of theorists’ wishful thinking. . . at any rate, if they existed, then they could not be detected.[4]”

The opportunity to confirm the release of neutrinos during a supernova explosion occurred in 1987 when a supernova, visible to the naked eye, was observed in the Large Magellanic Cloud that neighbors our Milky Way galaxy. Calculations indicated that this supernova, dubbed SN1987A, should give rise to a neutrino burst at a density of 50 billion per square centimeter when it finally reached the earth. This neutrino burst, lasting just 12 seconds, was observed in the huge neutrino detectors at Kamiokande in Japan and also at Fairport, Ohio.

Thus SN 1987A provided a remarkable confirmation of the general picture of neutron star formation developed over the last fifty years. Importantly it also confirmed that the Urantia Paper got its facts right long before its “little neutral particle” was discovered and also long before the concept of neutrino-yielding supernovas achieved respectability.

¶ External links

| On divine truth | Volume 8 - No. 5 — Index | Geophysics—further prophecies: Continental Drift and Age of the Solar System |