© 1996 Ken Glasziou

© 1996 The Brotherhood of Man Library

. . . Local space-permeation by calcium is due to the fad that it escapes from the solar photosphere, in modified form by literally riding the outgoing sunbeams. . . . UB 41:6.3

How many of us have been puzzled by the section in The Urantia Book entitled Calcium, the Wanderer of Space? Well, the main human sources used in composing this presentation have been discovered—thanks to the unique gifts of reader, Matthew Block, and his dedicated and unrelenting utilisation of those gifts in tracking down some of the “human concepts” (UB 0:12.12), “human thought patterns”“ (UB 121:8.12), and “cosmological statements” defined in the book as “never inspired.” (UB 101:4.5) That source was an “Evening Discussion” course, entitled “Stars and Atoms,” presented by Sir Arthur Eddington to the British Association in Oxford in August, 1926. In the hope that some adequately qualified person among our readers will now be inspired to make a comparative analysis of Eddington’s and The Urantia Book’s concepts about the wandering stone of the cosmos, relevant extracts from Eddington’s lectures are appended. It appears to be available on microfilm from Ohio State University, but, if necessary, we at Innerface International, Australia, undertake to provide a copy of what we have.

From “Stars and Atoms” by Sir Arthur Eddington:

P. 66. Just as the spectroscope can tell us that the sun is turning around . . . so it can tell us that certain stars arc wandering round an orbit, and therefore are under the influence of a second star which may or may not be visible itself. But here again we sometimes find “fixed” (spectral) lines which do not change with the others. Therefore somewhere between the star and the telescope there exists a stationary medium which imprints these lines on the light. This time it is not the earth’s atmosphere (as it is with oxygen). These lines belong to two elements, calcium and sodium, neither of which occur in the atmosphere. Moreover, the calcium is in a smashed state, having lost one of its electrons, and the conditions in our atmosphere are not such as would cause this loss. There seems to be no doubt that the medium containing the sodium and ionized calcium—and no doubt many other elements which do not show themselves—is separate from the earth and the star. It is the “fullness” of interstellar space aready mentioned. Light has to pass one atom per cubic inch all the way from the star to the earth, and it will pass quite enough atoms during its journey of many hundred billion miles to imprint these dark lines on its spectrum.

At first there was a rival interpretation. It was thought that the lines were produced in a cloud attached to the star-forming a kind of aureole round it. The two components travel in orbits round each other, but their orbital motion need not disturb a diffuse medium filling and surrounding the combined system. This was a very reasonable suggestion, but it could be put to the test. The test was again velocity Although either component can move periodically to and fro within the surrounding cloud of calcium and sodium, it is clear that its average approach to us or recession from us taken over a long time must agree with that of calcium and sodium if the star is not to leave its halo behind. Professor Plaskett with the 72-inch reflector at the Dominion Observatory, B.C., carried out this test. He found that the secular or average rate of approach of the star was in general quite different from the rate shown by the fixed calcium or sodium lines… Plaskett went further and showed that whereas the stars themseves had all sorts of individual velocities, the material of the fixed lines had the same or nearly the same velocity in all parts of the sky, as though it were one continuous medium throughout interstellar space. I think there can be no doubt that this research demonstrates the existence of a cosmic cloud pervading the stellar system. The fullness of interstellar space becomes a fact of observation and no longer a theoretical conjecture.

The system of the stars is floating in an ocean . . . an ocean that is so far material that one atom or thereabouts occurs in each cubic inch. It is a placid ocean without much relative movement; currents exist, but they are of a minor character and do not attain the high speeds commonly possessed by the stars. [Is this concept at variance with our Big Bangers’ view of the expanding universe?]

P. 67/9. . . Why are calcium atoms ionized? . . . even in the depths of space . . . some of the light-waves are quite powerful enough to wrench a first or second electron away from the calcium atom . . . (although) only very infrequently . . . The other side of the question is the rate of repair, and in this connection the low density of the cosmic cloud is the deciding factor. The atom has so few opportunities for repair. Roving through space the atom meets an electron only about once a month, and it by no means follows that it will capture the first one it meets . . . a calculation indicates that most of the calcium atoms in interstellar space have lost two electrons; these atoms do not interfere with the light and give no visible spectrum. The affixed lines" are produced by atoms temporarily in a better state of repair with only one electron missing; they cannot amount at any moment to more than one-thousandth of the whole number, but even so they will be sufficiently numerous to produce the observed absorption.

P. 70. The Sun’s Chromosphere

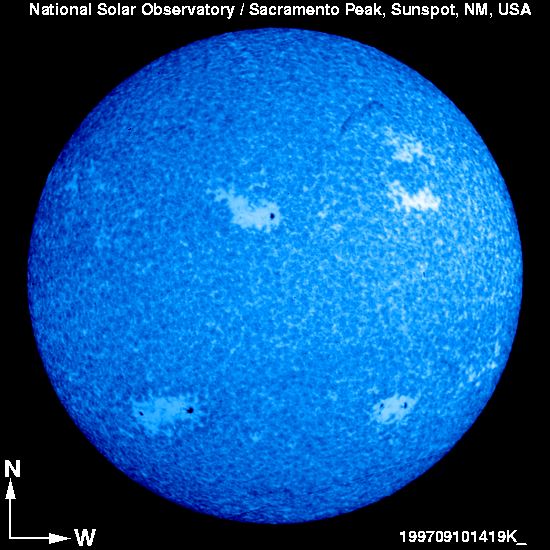

. . . we are back to the outer parts of the sun. Fig. 10 shows one of the huge prominence flames which from time to time shoot out of the sun. The flame in this picture was about 120,000 miles high. . . . The flames consist of calcium, hydrogen, and several other elements.

We are concerned not so much with the prominences as with the layer from which they spring. The ordinary atmosphere of the sun terminates rather abruptly, but above it there is a deep though very rarefied layer called the chromosphere consisting of a few selected elements which are able to float—float, not on the top of the sun’s atmosphere, but on the sunbeams. The art of riding a sunbeam is evidently rather difficult, because only a few of the elements have the necessary skill. The most expert is calcium. The light and nimble hydrogen atom is fairly good at it, but the ponderous calcium atom does it best.

The layer of calcium suspended on the sunlight is at least 5,000 miles thick. We can observe it best when the main part of the sun is hidden by the moon in an eclipse; but the spectroheliograph enables us to study it to some extent without an eclipse… the conclusions about the calcium chromosphere that I am going to describe rest on a series of remarkable researches by Professor Milne.

P. 71. How does an atom float on a sunbeam? The possibility depends on the pressure of light to which we have already referred (p.26). The sunlight travelling outwards carries a certain outward momentum; if the atom absorbs the light it absorbs the momentum and so receives a tiny impulse outwards. This impulse enables it to recover the round it is losing in falling back towards the sun. The atoms in the chromosphere are kept floating above the sun like tiny shuttlecocks, dropping a little and then ascending again from the impulse of the light. Only those atoms which can absorb large quantities of sunlight in proportion to their weight will be able to float successfully. We must look rather closely into the mechanism of absorption of the calcium atom if we are to see why it excels the other elements.

The ordinary calcium atom has two rather loose electrons in its attendant system; . . . Each of these electrons possesses a mechanism for absorbing light. But under the conditions prevailing in the chromosphere one of the electrons is broken away, and the calcium atoms are in the same smashed state that gives rise to the ‘fixed lines’ in the interstellar cloud. The chromospheric calcium thus supports itself on what sunlight it can gather in with the one loose electron remaining. To part with this would be fatal; the atom would no longer be able to absorb sunlight, and would drop like a stone. It is true that after two electrons are lost there are eighteen remaining; but these are held so tightly that the sunlight has no effect on them . . .

P. 72. There are two ways in which light can be absorbed. In one the atom absorbs so greedily that it bursts, and the electron scurries off with the surplus energy. That is the process of ionization . . . Clearly this cannot be the process of absorption in the chromosphere because, as we have seen, the atom cannot afford to lose the electron. In the other method of absorption the atom is not quite so greedy. It does not burst, but it swells visibly. To accommodate the extra energy the electron is tossed up into higher orbit. This method is called excitation (cf. p. 59). After remaining in the excited state for a little while the electron comes down again spontaneously. The process has to be repeated 20,000 times a second in order to keep the atom balanced in the chromosphere.

The point we are leading up to is this. why should calcium be able to float better than other elements? It has always seemed odd that a rather heavy element . . . should be found in these uppermost regions where one would expect only the lightest atoms. We see now that the special skill demanded is to be able to toss up an electron 20,000 times a second without ever making the fatal blunder of dropping it. That is not easy even for an atom. Calcium scores because it possesses a possible orbit of excitation only a little way above the normal orbit so that it can juggle the electron between the two orbits without serious risk. . . .

P. 73. The average time occupied by each performance is 1/20,000 of a second. This is divided into two periods. There is a period during which the atom is patiently waiting or a light wave to run into it and throw up the electron. There is another period during which the electron revolves readily in the higher orbit before deciding to come down again. Professor Milne has shown how to calculate from observations of the chromosphere, the durations of these periods. The first period depends on the strength of the sun’s radiation. But we focus attention on the second because it is a definite property of the calcium atom, having nothing to do with local circumstances . . . Milne’ s result is that a electron tossed into the higher orbit remains for an average time of a hundred-millionth of a second before it spontaneously drops back again. [1] I may add that during this brief time it makes something like a million revolutions in the upper orbit. . . .

P. 74. There is no prospect of measuring the time of relaxation of the excited calcium atom in a different way. [Is this still true in 1996???] . . .

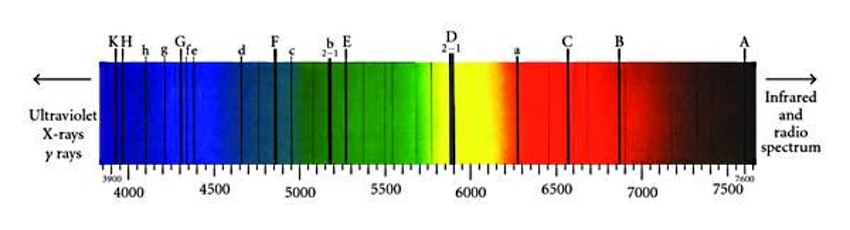

The excitation of the calcium atom is performed by light of two particular wave-lengths, and the atoms in the chromosphere support themselves by robbing sunlight of these two constituents. It is true that after a hundred millionth of a second a relapse comes and the atom has to disgorge what it has appropriated; but in re-emitting the light it is as likely to send it inwards as outwards, so that the outflowing sunlight suffers more loss than it recovers. Consequently, when we view the sun through this mantle of calcium the spectrum shows a gap or dark lines at the two wave lengths concerned. These are denoted by the letters H and K. They are not entirely black, and it is important to measure the residual light at the centre of the lines, because we know that it must have an intensity just strong enough to keep calcium atoms floating under solar gravity; as soon a the outflowing light is so weakened that it can support no more atoms it can suffer no further depredations, and so it emerges into outer spac with this limiting intensity. The measurement gives numerical data for working out the constants of the calcium atom including the time of relaxation mentioned above.

P. 75. The atoms at the top of the chromosphere rest on the weakened light which has passed through the screen below; the full sunlight (at the base of the chromosphere) would blow them away. . . . Owing to the Doppler effect, a moving atom absorbs a rather different wave-length from a stationary atom; so that if for any cause an atom moves away from the sun, it will support itself on light which is a little to one side of the deepest absorption. This light, being more intense than that which provided a balance, will make the atom recede faster. The atom’s own absorption will thus gradually draw clear of the absorption of the screen below. . . . (hence) there is likely to be an escape of calcium into space.

P. 76. By Milne’s theory we can calculate the whole weight of the sun’s calcium chromosphere. Its mass is about 300 million tons—less than the tonnage handled by British railways every year. One scarcely expects to meet with such a trifling figure in astronomy. I think that solar observers must feel rather hoaxed when they consider the labour that they have been induced to spend on this airy nothing. But science does not despise trifles. And astronomy can still be instructive even when, for once in a way, it descends to common place numbers.

“Stars and Atoms”, p. 66-76, Sir Arthur Eddington, Yale University Press, New Haven; Oxford University Press, London.

Question to readers

The Urantia Book (UB 41:6.5) gives a figure of one one-millionth of a second for the relaxation time of the excited state of calcium compared with Eddington’s one hundred-millionth of a second. Is The Urantia Book’s figure a typographical or copying error, or some such, or is it a deliberate correction by the revelators of Professor Milne’s calculations??? Can any readers respond?

¶ External links

- This article in Innerface International website: https://urantia-book.org/archive/newsletters/innerface/vol3_3/page16.html

¶ References

- “Stars and Atoms”, p. 66, Sir Arthur Eddington, Yale University Press, New Haven; Oxford University Press, London. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.173636