© 1995 Ken Glasziou

© 1995 The Brotherhood of Man Library

From Freeman Dyson, “From Eros to Gaia” (Penguin Books, London, 1992)

In large suns—small circular nebulae—when hydrogen is exhausted and gravity contraction ensues, if such a body is not sufficiently opaque to retain the internal pressure of support for the outer gas regions, then a sudden collapse occurs. The gravity-electric changes give origin to vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential, and such particles readily escape from the solar interior, thus bringing about the collapse of a gigantic sun within a few days. It was such an emigration of these “runaway particles” that occasioned the collapse of the giant nova of the Andromeda nebula about fifty years ago. This vast stellar body collapsed in forty minutes of Urantia time. (UB 41:8.3)

Freeman Dyson is a professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. In recent years he has taken to writing historical material, for most of which he was a either a participant or had personal knowledge of the participants. The section he devotes to astrophysicists, Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade is of great interest to scientifically-minded Urantia Book readers as it describes the history of discovery of neutron stars. What follows is an extract:

“Once in their lives, when Zwicky and Baade were both young and before they had become enemies, before either Zwicky’s 18-inch telescope or Baade’s 200-inch existed, they wrote together a theoretical paper of extraordinary originality. Their paper appeared in 1934 with the title, “Cosmic rays from Supernovae.” This was just two years after James Chadwick had discovered the neutron. At the end of their paper Baade and Zwicky put the following paragraph:”

“With all reserve we advance the view that a supernova represents the transition of an ordinary star into a neutron star consisting mainly of neutrons. Such a star may possess a very small radius and an extremely high density. As neutrons can be packed much more closely than ordinary nuclei and electrons, the gravitational packing energy in a cold neutron star may become very large, and under certain conditions may far exceed the ordinary nuclear packing fractions. . . ”

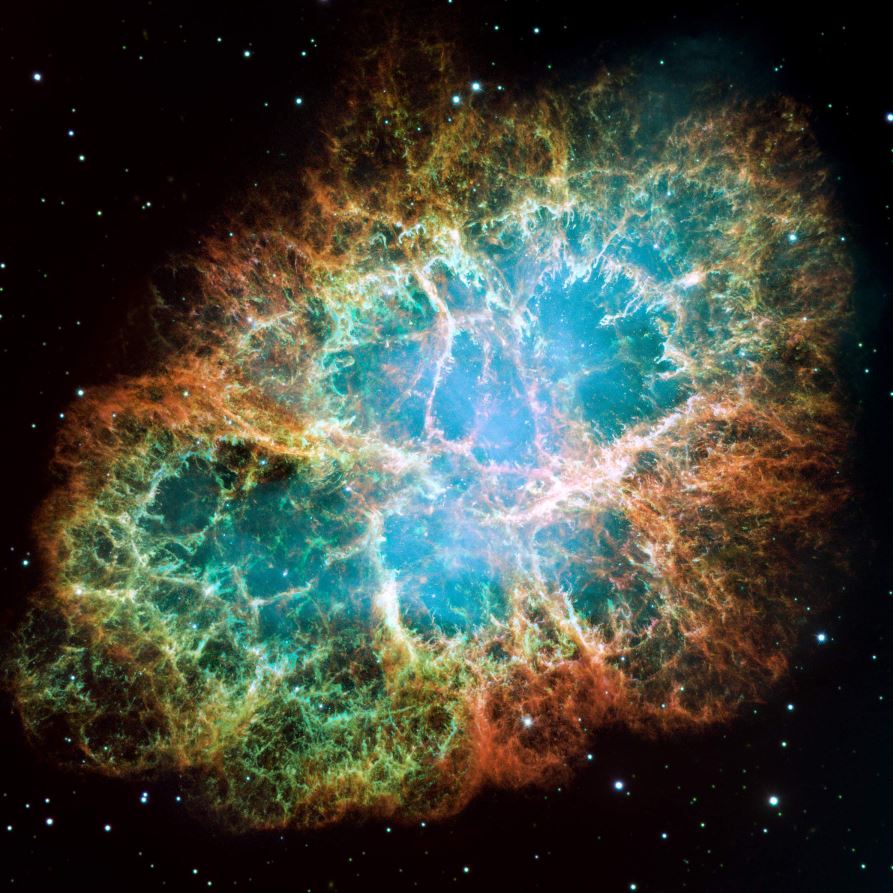

Freeman Dyson continues: “These remarks of Baade and Zwicky were ignored for a long time [except in The Urantia Book]. They were ignored by astronomers for thirty-three years, until neutron stars were discovered by radio astronomers. Now we know that almost everything Baade and Zwicky were saying in 1934 was true. . . If they had remained friends, neutron stars may have been discovered . . . in 1942 instead of 1967. It happened that in 1942 Baade used the 100-inch telescope to take the classic pictures of the Crab Nebula, the most spectacular visible remnant of a supernova. Baade knew the Crab was the debris from the supernova explosion of 1054. He also knew that there is a peculiar star at the center of the nebula which he suspected of being the stellar remnant of the explosion. According to the Baade-Zwicky paper of 1934 it ought to be a neutron star. Baade asked his friend Rudolf Minkowski to take a spectrum of the star. Minkowski, using the 100-inch telescope, found it completely featureless, with no lines at all, unlike any other star in the sky. Minkowsky calculated the temperature of the star and found it to be half a million degrees, ten times as hot as any other star. . . But Baade and Minkowski did not go further. . . they did not mention, in their 1942 paper, the possibility that it might be a neutron star. . . How can their disinterest be explained. . . the simplest hypothesis is that the more speculative part of the 1934 Baade-Zwicky paper was written by Zwicky alone (the two were now sworn enemies). From a human point of view Baade’s reaction is understandable. But from a scientific viewpoint it was a great opportunity missed.”

Dyson writes, “A few years ago we had a Princeton graduate student observing the thirty times a second flashes of the Crab and measuring the period with a 1-meter telescope under the polluted sky of New Jersey. Zwicky could have done just as well (in 1942) with his 18-inch telescope under the clear sky of Palomar. All he needed was a recording photo-detector. . . this was the way the flashes were finally discovered in 1969 by Cocke, Disney, and Taylor. Zwicky could have done it twenty-five years earlier.”

So it does not matter much if we accept the 1934/5 date of receipt of the Urantia Paper 41 or the date of publication of The Urantia Book in 1955—the paragraph cited above from UB 41:8.3 remains a remarkable statement about the formation of neutron stars, and the more so because it also describes the release of vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential. These are the neutrinos that are now known to carry away close to 99% of the energy of the explosion. The existence of neutrinos was proposed by Wolfgang Pauli in 1932 but when Nobel laureate, Enrico Fermi, submitted a paper on neutrinos to “Nature” in 1933, it was rejected as being too speculative. The existence of neutrinos was conclusively demonstrated by Cowan and Reines in 1956. Direct confirmation of the neutrino burst accompanying a supernova was obtained in 1987 from observations of a supernova in our satellite galaxy, the Cloud of Magellan. The tiny, unreactive neutrino particles can make the journey from the nuclear core of a star to its surface in about 3 seconds compared with the million-year journey taken by light-energy to make the same trip. This is the opaqueness which is related to the back-pressure counteracting gravitational collapse. Opaqueness to neutrinos occurs at a density of about 400 billion g/cc.

Depending on its initial mass, once the silicon- burning phase commences, the collapse of a star to the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.2-1.5 solar masses may take hours or days, but the subsequent collapse may be less than a second.

It would be of great interest to discover the actual dates for publication of any pre-1950’s papers that provide information on the rates of collapse of large stars and/or the essential role of the “tiny particles devoid of electric potential” (neutrinos) that are the vehicle for explosive transit of energy from the core of collapsing stars.