© 2016 Ralph Zehr

© 2016 Association Francophone des Lecteurs du Livre d'Urantia

¶ Ralph D. Zehr

¶ Professional biography

Ralph D. Zehr received his medical degree from SUNY Upstate Medical Center, Syracuse, New York, in 1964. After a year of residency at Harrisburg Hospital in Pennsylvania, and a year of postdoctoral fellowship at the University of London, England, where he received the Diploma in Clinical Tropical Medicine (DCTM Lon.) he served two more years in Ghana, West Africa. Returning to the United States, he completed a three-year residency at Robert Packer Hospital in Sayre, Pennsylvania, specializing in radiology. After completing his residency, he immediately joined the medical service management team and spent his entire medical career at the Guthrie Clinic, a large regional multispecialty group of several hundred physicians and primary care providers with three hospitals and a large outpatient population located in rural southern New York and northern Pennsylvania. This unit functions as a large integrated medical infrastructure focusing on high-quality medical care, basic and clinical medical research and a wide range of medical education.

He devoted a significant portion of his time to teaching radiology to technologists, junior and senior medical students, radiology residents, and gave frequent presentations and lectures to various groups of the senior medical staff. He held an academic appointment with SUNY Upstate Medical Center for many years. For ten years, he served as editor-in-chief of the Guthrie Medical Journal, a regional medical journal, with a circulation of over 7,600 subscribers, primarily physicians.

During his career, his administrative responsibilities were considerable. He served for a period of eight years on the Executive Committee of the Medical Staff, including two years as secretary, two years as vice president, two years as president and two years as past president. He was appointed chairman of the Department of Radiology requiring supervision of all radiological diagnostic services, including educational activities, at the three hospitals and in the outpatient clinics in the region.

Since then, he has had no further clinical responsibilities, but continues to serve on the Board of Trustees of the Donald Guthrie Foundation which oversees education and research programs, two areas that have been of great personal interest throughout his career.

Preparing this paper, which focuses primarily on molecular cellular biology, has been a truly exciting experience. The technological advances that have made it possible to study cell biology at the molecular level have been truly astonishing. In many ways, they parallel the advances that have occurred in radiological imaging that have continued throughout his career. 80 to 90% of the imaging data generated in the field of radiology when he retired were not even imagined when he began his career! Many of these same technological advances have also contributed to our ability to image intracellular activity at the molecular level.

¶ Personal biography

The Urantia Book, with its profound and innovative teachings, entered the lives of Ralph and his wife Betty in the fall of 1967 during a medical mission to Ghana. Its effect on their lives was immediate and continues forty years later. Words cannot express their gratitude for finding the book so early in their parenting and professional careers. Betty and Ralph have two adult children, both readers, and three grandchildren. Betty is a retired public school teacher and reading specialist, Ralph is a retired radiologist since 2009 after 45 years of medical practice.

Ralph is a charter member of the Urantia Association of Pennsylvania where he holds several executive positions. Betty and Ralph have hosted many biannual meetings at their home for the association and have also hosted several study groups for many years.

They are both heavily involved in the management of the UBIS school, of which they are part as trustees and give courses that are very popular and appreciated. They also serve on many other national committees. Ralph is also an Associate Trustee of the Urantia Foundation, highly regarded for his experience and helpfulness.

¶ Single-celled organisms The Cambrian explosion — Nanomachines

So Many Moving Parts — How Do They Fit Together?

By Ralph D. Zehr M.D.

¶ Unicellular organisms

IT IS GENERALLY THOUGHT that life began as a single-celled organism. An understanding of the morphology and function, particularly of single-celled organisms, is therefore essential to any serious study of the origin of life. All living cells belong to one of two groups: prokaryotes or eukaryotes.

Prokaryotes appear much simpler, lacking most organelles except ribosomes. They contain a region in which DNA molecules are relatively concentrated in the central region of the cell, in contrast to eukaryotes in which intracellular DNA is enclosed in a nuclear membrane or envelope.

E. coli has been the most studied prokaryote because of its simplicity and the speed and ease with which it reproduces. Its entire genome has been deciphered. Although one might have expected to find much simpler proteins and less complex intermolecular interactions than those seen in eukaryotes, this was not the case. Electron microscopy revealed a relatively large collection of DNA molecules in an area called the nucleoid located at or near the center of the organism, as well as numerous small ribosomes in the cytosol. Complex interactive processes take place between DNA and mRNA as well as protein synthesis. E. coli have multiple flagella that give them astonishing mobility. They can respond to their environment by moving toward food sources, as well as slowing down their metabolic rate when food is scarce. They can reproduce rapidly by dividing once every 20 minutes under ideal circumstances. A well-prepared culture medium, inoculated with E.coli, incubated overnight can produce millions of identical living organisms ready for study the next morning.

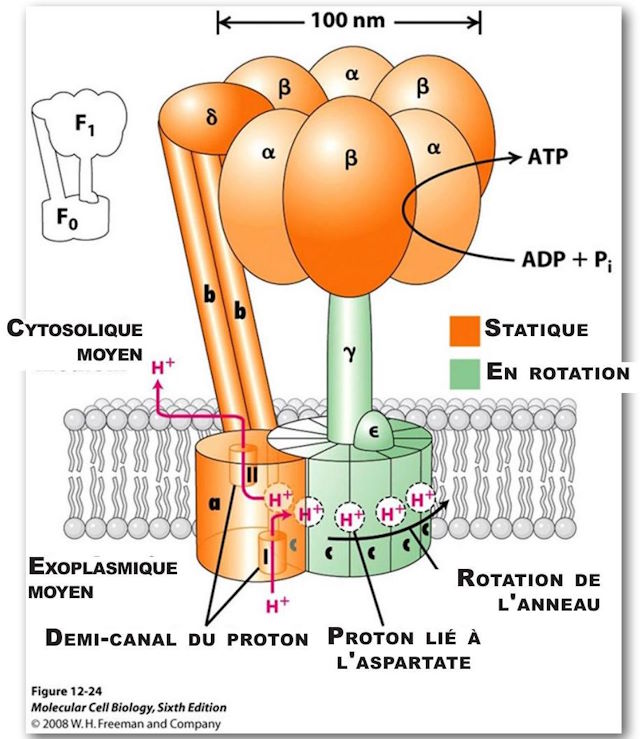

One can hardly mention the role played by E. coli in research without acknowledging how it helped to elucidate the “proton motive force” and the associated chemiosmotic hypothesis, proposed by Peter Mitchell in 1961. He recognized a link between the transfer of an electron and the ATP-generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase. He was convinced that there was an electrical phenomenon associated with the chemical process. There was a process of electron transfer, in which electrons pass an electron gradient along a chain of several molecules or along cell membranes, giving up their energy in small increments as they pass. In this process, protons accumulate outside the membrane, building up a proton radiant known as the “proton motive force.” They then pass their gradient, to motive machines such as ATP synthase. It actually took some 16 years for this theory to become widely accepted. In 1978 Mitchell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Not only did his hypothesis of chemoosmotics become well established, but it was also discovered that these phenomena occur in many bacteria, in animal mitochondria, and in chloroplasts throughout the plant kingdom. (1)

Another example of what we can expect to find in further study of prokaryotes is the recent documentation of aquaporin in E.coli, which is highly specific and shows a rapid rate of water flow through its channels. It is expected to provide a useful model for further study of aquaporins which are a large complex of macromolecular proteins housed in cell membranes and are generally responsible for controlling the flow of water and glycerol into and out of cells. (2)

Although prokaryotes show relatively little subcellular structure, there appears to be significant subcellular organization or intracellular compartmentalization at the molecular level. Microbiologists Lucy Shapiro and Richard Losick stated, “The use of gold-labeling electron microscopy and fluorescent microscopy to study the subcellular organization of bacterial cells has revealed a surprising extension of protein compartmentalization and localization.” They go on to describe examples such as DNA polymerase, dividing protein cells, and the bacterial cytoskeleton. (3)

Eukaryotes populate bodies throughout the animal kingdom and represent our general concept of a typical cell. They exhibit extensive intracellular compartmentalization with a nucleus surrounded by a galaxy of highly sophisticated organelles that perform specific functions. Their energy systems are well defined and highly specialized. Chloroplasts in plants function like solar panels, transforming energy from the visible spectrum of sunlight into chemical energy in the form of sugars, starches, cellulose, and ATP, while animal mitochondria transform chemical energy stored in ingested sugars and starches, as well as fatty acids, into ATP. Energy can also be extracted from unnecessary ingested proteins and amino acids if the diet contains them in excess.

Franklin M. Harold, professor emeritus of biochemistry at Colorado State University, whose professional career spans 40 years of research focused on microorganisms, offers us this interesting perspective on our understanding of life based on our knowledge of cells. In his recent book The Way of the Cell, he stated: “Biochemists rightly insist that when you dissect cells you find nothing but molecules; no special forces of life, no cosmic plan, only molecules whose contortions and couplings underscore and explain everything the cell does. Thus Max Perutz, reflecting on the mechanisms by which E. coli senses a source of nutrients and swims toward it, found nothing that could not be ‘reduced to chemistry.’” I share this commitment to a material conception of life, but it makes it doubly necessary to remember that before cells were dissected, to the extent that they were alive at all, they displayed capacities that went beyond chemistry. Homeostasis, intentional behavior, reproduction, morphogenesis, and descent with modification are not part of the vocabulary of chemistry but indicate a higher level of order. Just as a catalog of small parts approaches completion, the transition from molecular chemistry to the supramolecular order of the cell emerges as a prodigious challenge to the imagination. Make no mistake; we touch here, if not the very secret of life, at least an essential layer of this multilayered mystery. For if life is to be convincingly explained in terms of matter and energy, organization is all that separates a soup of chemicals from a living cell." (4) (emphasis added)

¶ The Cambrian Explosion: How Does It Fit In?

The expected rate of appearance of new phyla, as predicted by Darwin’s theory, would follow a relatively smooth, logarithmic or exponential curve over time. Resulting from small, incremental changes in the size and complexity of living organisms and based on a long series of random mutations of the genetic code, followed by intermediate periods of trial and error resulting in the selection of the fittest, one would expect to find a fossil record showing the gradual changes of primitive phyla from simple organization and body plan through many progressive stages to more complex morphological arrangements of body parts characteristic of more advanced phyla. One would therefore expect to see a long, extended spectrum of new phyla extending over centuries, showing a pattern of branching as new forms branch off randomly in all directions.

But that is not what happened based on the fossil record we have. During the Cambrian explosion as recorded in the two fossiliferous deposits of the Burgess Shale in eastern British Columbia, Canada, discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1909 and in the more recently studied, very well preserved and better described Cambrian fossils found in China near Chengjiang, a very different story emerges. The two deposits, located almost halfway around the world from each other, show a surprisingly similar picture of a biological Big Bang (5), (6) in which many phyla and other recognized body plans appeared in an instant of geologic time representing approximately 0.1% of the Earth’s total geologic history.

But, why do we not find fossil evidence of simpler precursor organisms that would show a gradual progression of complexity leading to each feature of a unique individual plan of each phylum? In fact, there is very little evidence of intermediate forms in any of the phyla. The identified phyla show considerable morphological stability. In other words, we are unable to isolate fossils that show significant evidence of simpler organisms gradually progressing in complexity and leading to the more advanced body plan of the observed phylum. Nor do we find any fossil record either in a specific geologic time or throughout geologic history that offers morphological evidence of a long series of gradual progressive steps linking the phyla or confirming an evolutionary progression from simpler organisms.

A discussion of all the phyla identified in Cambrian deposits is beyond the scope of this presentation, but a list and brief discussion of the more familiar ones seems appropriate. This list includes: Brachiopods, Eldoniaiods, Annelids, Ctenophores, Hyoliths, Chordates, and Arthropods.

Chordates, characterized by the presence of a notochord, include all vertebrates. An interesting finding in the Chengjiang fossil deposit is the presence of the three chordate subphyla, cephochordates, craniates, and urochordates.

In his book Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, Stephen Jay Gould raises two questions related to the Cambrian explosion: (1) Why did multicellular life appear so late? (2) Why do these anatomically complex creatures have no simple direct precursors in the Precambrian fossil record? (7)

Fossil deposits from the Cambrian period in China show the most exquisitely fine details as well as many parts of soft tissues: "The Lower Cambrian sediments near Chengjiang have preserved fossils of such excellence that soft tissues and organs, such as eyes, intestines, stomachs, digestive glands; sensory organs, epidermis, hairs, mouths and nerves, can be observed in detail. Even fossilized embryos of sponges are present in the Precambrian strata near Chengjiang. (8)

“Cambrian strata show soft body parts of jellyfish-like organisms (known as Eldonia) such as radiating watery canals and rings of nerves. These fossils even contain the contents of the intestines of several different kinds of animals as well as the residue of undigested food in their feces.” (9)

Recent work by Michael S.Y. Lee and colleagues at the University of Adelaide compared relative evolutionary rates of development and molecular development during the Cambrian Explosion with that from the Cambrian period to modern times. They chose to study arthropods because they are such a large and diverse group of animals living during the Cambrian period and since. Using 395 morphological characters, 62 protein-coding genes, and 20 calibration points from the fossil record, the authors inferred evolutionary histories using a number of analytical methods, and their relationship results are consistent with other recent research. (10) They concluded that the rate of evolution of morphological change during the Cambrian period was four times the average rate since the Cambrian period, while the estimated average rate of molecular evolution during the Cambrian period was five times the average rate since that time. (11) (See Figures 1 and 2 below)

The rate of morphological and molecular evolution of arthropods increased 4-5 times during the Cambrian explosion.

It is very fortunate that we have found a fossil bed which contains such well-preserved specimens in which many of the soft parts can be clearly identified and fine detailed morphology is preserved. The informative value of these fossil beds is multiplied by the fact that they illuminate such a critical and unique period in the evolutionary history of life on our planet. If paleontologists were captivated by the discovery of the Burgess Shale fossils, it is reasonable to assume that they were ecstatic by the discovery of the Chengjiang fossil bed. In general, organisms without skeletal structure rarely leave a fossil record of their existence. In the case of the Cambrian explosion we find that the pages of the great stone book of geological history which cover the Cambrian explosion are among the best preserved in the entire book.

At the time of Darwin, precise dating of rocks by radiometric means was not available. Fossils were classified by phylogenetic relationships. At the time of the discovery of the Burgess Shale fossil deposits the best estimate of their age was during the Cambrian period, which was thought to have begun about 570 million years ago and ended about 510 million years ago. This left a window of 30 to 60 million years for the formation of the Burgess Shale fossils. In 1993, a Cambrian deposit in Siberia was identified that contained zircon crystals nearby, just above and just below. Based on radiometric dating they were found to be 525 and 530 million years old. These very precise measurements narrow the window of fossil deposition, establishing the Cambrian explosion of living organisms at an instant in geological time. If we take the perspective of a 24-hour day to represent the entire history of life on Earth, which is estimated to be about three billion years, the Cambrian explosion occupied about half a minute early in the first hour of multicellular life on our planet.

This scenario bears little resemblance to the process Darwin described in which he envisioned living organisms exhibiting an extensive series of numerous, slight modifications over a long period of time, eventually resulting in new body plans that were better adapted to the environment and more capable of survival.

Another unexpected factor that characterizes the organisms depicted by the Cambrian explosion is the apparently sudden appearance of organisms representative of most phyla appearing to coexist together. Phyla represent the highest levels of the divisions of animal life as we understand them. In a single instant of geologic time, most, if not all, of the major divisions of animal life appeared. Instead of the simplest life forms developing from the bottom up, driven by chance genetic mutations that would cause many small alterations in morphology and physiology that would prove beneficial to their survival, and would lead to many large and distinct divisions of living organisms, we see an apparently top-down development in which these major divisions of animal life show much of the body plans that have ever appeared on Earth. One might conclude that the Cambrian explosion depicts the “origin of phyla” rather than the “origin of species.” The origin of species would come much later as a result of a sifting and sorting of basic life forms, ultimately leading to the phenomenal diversity of living organisms that we all observe wherever we look.

As time has passed, the basic dilemma facing Darwinism has changed. Again, Gould sums up the situation succinctly, “Darwin has been vindicated by a rich Precambrian record, all discovered within the last thirty years. Yet the peculiarity of this evidence does not fit Darwin’s predictions of a continued rise in complexity toward Cambrian life, and the problem of the Cambrian explosion remains as persistent as ever—if not more so, since our confusion now rests on knowledge rather than ignorance of the nature of Precambrian life.” (12)

¶ What Are The Foundations Of Living Organisms?

Atoms and molecules are the building materials from which all living organisms are made. All living organisms depend on thousands of chemical reactions that take place continuously and simultaneously throughout their lives. They are exquisitely coordinated, constantly modified and controlled by the central nervous system, continuously responding to feedback from internal stimuli, adjusting to changing external environments, directed by thousands of genetic instructions, and greatly influenced by carefully balanced hormonal influences. All of these factors that control and direct living creatures are based on the chemical interactions within the living organism. How the limited number of different elements that make up the many trillions of molecules that carry out these incredibly complex processes in all living organisms can perform such diverse functions and, at the same time, maintain the stability and functional predictability that is so essential to life, remains an unsolved mystery.

Another interesting consideration is the fact that the very material of which living organisms are composed is constantly being replaced by other similar atoms. It is difficult to estimate the rate of replacement of many of the atoms that make up the parts of our body because it varies greatly from tissue to tissue, from organ to organ, however, on average this replacement takes place many times over the course of a lifetime. We know that the proteins within a given cell are constantly being built and broken down and that the basic amino acids are constantly being recycled. Entire cells are also constantly being replaced by younger cells. Our red blood cells are recycled every 60 to 90 days and the entire endothelial lining of our small intestine, responsible for absorbing the nutrients we need, is recycled every five days on average. (13)

¶ Types of Chemical Bonds That Hold Parts Together

In living organisms atoms are held together by a series of chemical bonds of different types and varying lengths.

Covalent bonds are by far the strongest chemical bonds. These covalent bonds form when there is an exchange or sharing of one or more electrons in the outer shells of two or more separate atoms. They can be single, double, or triple. The most common double covalent bonds are between carbon and oxygen, carbon and nitrogen, carbon and carbon, and phosphorus and oxygen. The covalent bond between phosphorus and oxygen is of particular interest because it is the energy inherent in this bond that is used to transfer, distribute, and energize essentially every physiological function throughout the animal kingdom in the form of ATP.

There is a group of non-covalent bonds that are much less energetic but equally important. Non-covalent bonds are important for stabilizing macromolecules, particularly for maintaining their exact folding configuration. Of these, hydrogen bonds are of great importance. They are formed primarily between hydrogen and oxygen and hydrogen and nitrogen. They are strongest when positioned in a straight line, however, very frequently non-linear angular hydrogen bonds contribute more effectively to stabilizing the three-dimensional configuration, known as the ‘conformation’, of large protein molecules. The precise folding of the long chains of amino acids that form many macromolecular proteins is critical for their proper functioning. The same protein compound can have very different functions depending on how it is folded.

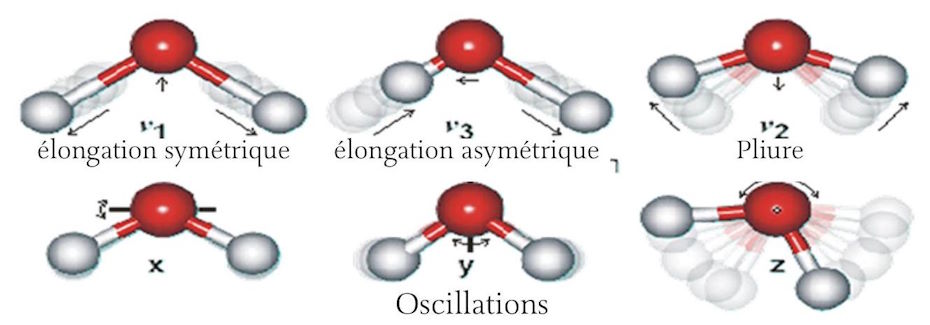

Hydrogen bonds are prevalent in water, whether it contains dissolved ions or is pure. Hydrogen bonds are typically twice the length of covalent bonds between like elements. The length of the covalent bond between hydrogen and oxygen in water is about thirteen nanometers ( nm ), while the hydrogen bond between hydrogen and oxygen in water is about twenty-seven nm in length. These are averages because the bonds are constantly changing length. See Figure 3 below. (A nm is one billionth of a meter.)

Van der Waals interactions are not specific and take place between all nearby atoms. They vary in length depending on the distance between the nuclei of adjacent atoms. The minimum distance is limited by the Van der Waals radius, which is equal to the radius of the atomic sphere occupied by a given nucleus and its associated electron cloud surrounding it. The Van der Waals force of attraction increases until it reaches a maximum and the repulsive force of the negatively charged electron clouds overlapping it balances this force of attraction. This phenomenon is known as Van der Waals contact. The force of this attraction is weak, measuring on the order of 1 kcal per mole. (One kcal is worth a thousand calories).

Another non-specific interactive weak force that acts on all atoms and molecules is that due to thermal energy. This is the phenomenon responsible for Brownian motion which can be observed indirectly by optical microscopy. All atoms and molecules that are in a fluid, such as liquids and gases, are subject to Brownian motion. The intensity of Brownian motion increases with increasing temperature. The energy level of Brownian interactions at body temperature is just under 1 kcal per mole.

Finally, there are ionic associations which mainly take place in solutions. These are very variable and weak attractions and repulsions between, respectively, ions of different charges and ions of similar charges. These associations vary according to the combined concentrations of all the ions in a given solution.

Relative strengths of non-covalent bonds:

- Hydrophobic packet, occurs in water solutions, connected to a dipole, very low thermal energy, slightly less than one kcal per mole.

- Ionic interactions, very weak, vary according to the concentration of ions in the solution.

- Van der Waals interactions, approximately 1 kcal per mole.

- Hydrogen bonds, from 1 to 5 kcal per mole

Relative strengths of several common covalent bonds:

- hydrolysis of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bond, 7.3 kcal per mole

- hydrolysis of the phosphoester bond, glyceryl -3 phosphates, 2.2 kcal per mole.

¶ The amount of the WATER Pole

A unique feature of the water molecule is its dipole moment. This results from the asymmetric configuration of the H2O molecule. The covalent bonds formed by the two hydrogen atoms with the oxygen atom make an angle of 104.5º between them rather than the 180º required by symmetry. (See Figure 3 below) There is a slightly positive charge associated with the hydrogen atoms and a slightly negative charge at the oxygen end of the molecule. Due to the asymmetry, this results in a slight electric dipole charge or moment running through the molecule.

This dipole moment of water makes it an excellent solvent. For example, when sodium chloride crystals are placed in water, the sodium and chloride atoms tend to dissociate and form ions that are positively and negatively charged, respectively. Because the outer electron of sodium is loosely attached and thus tends to be in possession of the chloride ion, the dipole moment of the water molecule can aid in this process by attracting the positively charged sodium ion to the negatively charged oxygen end of the water molecule, while the positively charged hydrogen end of the water molecule attracts the negatively charged chloride ion. In a similar manner, water is able to dissolve many different compounds, contributing to their ionic status in solution. The dipole moment of the water molecule is also productive of extensive hydrogen bond formation, both between water molecules and between other non-ionic molecules such as glucose, particularly with the [OH+] group of the sugar molecule. Similar to salt crystals, sugar crystals dissolve readily in water due to this slightly different mechanism. This phenomenon of many water molecules surrounding dissolved molecules is known as hydration or ‘hydrophobic packing’ and it occurs extensively in association with many of the large macromolecules responsible for the operation of the complex chemical reactions that sustain life. These reactions occur primarily when the molecules are dissolved in water. Liquid water is a highly dynamic substance. Not only are the molecules in constant motion due to Brownian motion which is directly related to temperature, but there is a constant internal motion within each water molecule in which the oxygen and hydrogen atoms move relative to each other causing a slight variation in their bond length. There are symmetrical motions, asymmetrical motions, vibrational motions, and seesaw motions of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms. In general, the motion of the hydrogen atom is much greater due to its relatively smaller size and mass. (See Figure 3 below) The presence of water in liquid form is generally considered to be absolutely essential to life. In many ways, it is the most remarkable compound in existence. Oxygen is absolutely essential to life as we know it. Hydrogen is, by far, the most abundant element in the universe. When hydrogen and oxygen are put together, they combine explosively to form water which is, by far, the most commonly used retardant as well as providing a unique medium in which the processes that characterize life can occur.

¶ Water Molecules

¶ The amphoteric nature of water

The amphoteric nature of water is its ability to act as both an acid and a base; it can donate a proton [H+] acting as an acid and can accept a [H+] acting as a base. Pure water is neutral. But pure water is rarely found in nature. Even rainwater, as it condenses in the atmosphere to form droplets and falls to the earth, dissolves small amounts of carbon dioxide from the air which form a weak carbonic acid.

H2O + CO2 = H2CO3

If ammonium is present in the atmosphere, it will be dissolved by falling raindrops and produce ammonium hydroxide which is a weak base.

NH3 + H2O = NH4OH

Pure water atoms partially dissociate providing equal amounts of hydronium ions

[H3O+ or H+] and hydroxide ions [OH-].

2 H2O = H3O+ + OH-

The concentration of hydrogen ions [H+] in blood plasma is very low, 0.00000004 moles per liter or 4 X 10-8 moles per liter. To avoid such an unwieldy number, the concept of pH was introduced, which is defined as: pH is equal to minus the logarithm of the concentration of hydrogen ions [H+], expressed in moles per liter. Thus, the concentration of hydrogen ions in plasma, expressed as pH, is 7.4. Normal human blood plasma is 7.3 to 7.5; the pH range compatible with life is 6.8 to 7.8. The pH is carefully controlled first by the respiratory rate which controls the amount of CO2 dissolved in the plasma, and then by the kidneys which remove excess acid or base generated by metabolism by a complex process of glomerular filtration and renal tubular reabsorption. As a result, normal urine tends to be acidic with a pH ranging from 5 to 8. Precise control of this narrow range of plasma pH is essential to life because abnormal pH can result in protein denaturation, causing unfolding and loss of function.

¶ Protein synthesis

Proteins are large molecular structures composed of many atoms of a relatively select group of elements. These form long chains of amino acids called polymers. When examining the basic composition of living organisms one is struck by the surprisingly narrow selection of elements that form the vast majority of protein atoms.

Water is by far the most prevalent compound in living organisms, accounting for 80 to 90% of the body’s weight. As a result, hydrogen is by far the most common element, accounting for about 50% of all atoms in living organisms, and oxygen is the second most common element. Other common elements in descending order of frequency are carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Additional elements that are occasionally encountered include calcium, potassium, iron, zinc, magnesium, manganese, fluorine, and iodine. We are all familiar with

Anemia due to iron deficiency and goiter due to iodine deficiency. The total number of essential elements in humans is 26, and for bacteria it is about 16. Proteins are composed of various combinations of 20 basic amino acids, nine of which are considered essential in humans. An essential amino acid is one that the human body is unable to synthesize from other protein sources and must therefore be supplied through the diet on a regular daily basis. Our body is capable of synthesizing the remaining 11 amino acids from ingested proteins. However, it is important to obtain a well-balanced intake of all nine essential amino acids on a daily basis. Protein synthesis depends on an adequate supply of all the specific amino acids required. If the amounts of one, or more, of the essential amino acids are insufficient, protein synthesis will be reduced accordingly. Careful analysis of living proteins indicates that more than 100 amino acids present result from modifications of the 20 basic amino acids by phosphorylation, glycosylation, hydroxylation, methylation, carboxylation, and acetylation.

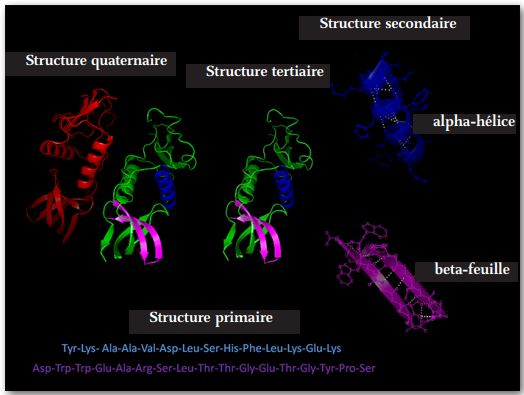

Protein synthesis occurs in four generally recognized steps. (See Figure 4 above)

The first step takes place in ribosomes which are large, highly complex organelles that reside in essentially all cells. They function as protein factories. They consist of massive, complex proteins with significant amounts of RNA. They can be located in the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum but most reside in the cytosol. Ribosomes receive instructions to produce a specific protein by means of a messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) delivered from the cell nucleus. It is produced by transcription, in the nucleus, and is an exact copy of a single, short, selected strand of DNA, except that the thymidine nucleotides in the DNA are replaced by uridine nucleotides in the RNA. The mRNA provides exact information as to the sequence of amino acids that are to be linked together, the number of copies to be produced, and instructions as to where and how the newly produced protein should be distributed. Polymers less than 40 amino acids in length are generally called peptides. Messenger RNA acts as a blueprint, and ribosomes manufacture the appropriate body parts exactly to specifications.

The second step takes place due to various non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydration. The result is the folding of the polymer into various configurations, the most common of which are: a random coil, an alpha helix, or a beta sheet.

The third step continues the second in that folding continues due to further interactions of non-covalent forces. A reversion of the third step of molecular folding can be due to higher than normal temperatures and abnormal fluctuations in pH level. The unfolding will interfere with the normal functioning of the protein. This process known as ‘denaturation’ can be reversed by correcting the underlying cause.

The fourth step is usually performed by large, complex macromolecules called chaperones which often exhibit a barrel configuration into which tertiary proteins are inserted and within their cavity the chaperones perform specific folding maneuvers resulting in the correct conformation of the molecule. The folding process may require more than one step, in which case the molecule may be transferred to a second chaperone or co-chaperone to complete the folding process. It is well established that identical proteins can perform entirely different functions depending on how the molecule is folded. This fourth folding process often requires energy such as an ATP molecule to complete the conformation process and release the now functional protein molecule into the cytosol.

Chaperones are usually very complex macromolecules that have themselves undergone fourth-step protein synthesis with a specialized chaperone. Thus, we have a “chicken and egg” situation. Here we have a special form of irreducible complexity in protein synthesis that depends on a system whose very system that is indispensable must have been synthesized previously.

¶ Intracellular Compartmentalization

Intracellular compartmentalization is a topic of great interest to cell biologists, biochemists, and molecular biologists. It has led to a paradigm shift in the way we view cell morphology and physiology. Over the past 40 years our knowledge of intracellular processes has exploded; virtually everything happened in a “black box” in Darwin’s time. Our current insight into the internal activities of molecules in living cells has been made possible by a range of astonishing molecular imaging and other investigative techniques that continue to advance rapidly. In 1976, X-ray imaging rapidly became a major tool for examining molecular activity. This was followed in the mid-1980s by the addition of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging and in the late 1990s by electron microscopy (EM). The rapid application of these tools to the study of cell biology has resulted in the number of new intracellular structures discovered each year since the mid-1970s growing exponentially from ten to a few thousand. (14)

Fifty years ago, the general concept of a living cell was that of a small packet of proteinaceous fluid enclosed in a two-layered phospholipid membrane in which various distinct structures such as the nucleus and several small organelles could be seen floating. We now recognize that the entire interior of the cell is occupied by distinct structures that perform specific functions. The concept that a cytoskeleton consists of microtubules that provide tracks or cables on which transport motors of various types move or carry intracellular cargo from one point to another is well established. We now know that the cytoskeleton is an extremely dynamic structure that is constantly being built, destroyed, and readjusted to accommodate intracellular activities. This condition has given rise to the concept of dynamic instability. Separate functional domains within the cell are associated with specific transmembrane proteins, usually in the form of alpha helices, responsible for the entry or exit of specific fragments, which is accomplished, in most cases, by active transport across the cell membrane. Alpha helices are tubular proteins, often with a central channel through which water, ions, and other small fragments can enter or exit the cell under careful control. They thus provide a conduit through which the fragments pass without contact with the phospholipids that form the cell membrane.

It is not well understood why these dynamic changes must constantly maintain cellular function. It is known that before mitosis there was an increase in microtubule activity in preparation for the formation of spindles, composed of microtubules, necessary for the separation of chromosome pairs. It has also been observed that mitochondria undergo constant alterations in which short strands fuse to produce a large spider-web configuration, followed by further separation into short segments. This could be a means of partially or completely eliminating a dysfunctional mitochondrion, and represent a process of healing or replacing dysfunctional proteins.

Intracellular compartmentalization results first from the distribution of organelles within the cell. Organelles are grouped according to their specific functions and the degree to which their functions are interrelated. Organelles are all essentially enclosed by highly specialized membranes. In most cells, the smooth endoplasmic reticulum and the rough endoplasmic reticulum both consist of highly folded membranes, the Golgi apparatus, which also has a folded structure, and the early endosomes and late endosomes, all are functionally related and tend to cluster together, occupying a major compartment within the cell. The membranes of these organelles tend to be compatible, allowing protein molecules and other fragments to pass from one to the other.

Ribosomes are complex macromolecules that function as protein factories and can be attached to a membranous surface such as the endoplasmic reticulum which can then serve as a storage area or delivery channel for newly synthesized proteins. Others are associated with the mitochondria. Many ribosomes, however, are located independently in the cytosol and release their proteins directly. A major function of the Golgi apparatus is to mark and prepare newly manufactured proteins for delivery into the cell or to package them for passage across the cell membrane and delivery to a distant site in the body via the blood stream.

The nucleus is usually located in the center of the cell and has large pores in its two-layered outer membrane; it allows mRNA to transmit specific instructions to the ribosomes as to exactly what type of protein and how many copies to make. ATP as well as various ions and other small fragments can pass into the nucleus through these pores.

Mitochondria also communicate directly with the cytosol, directly releasing manufactured ATP. ATP is the energy source for essentially all cellular functions. We will examine ATP synthase which is a large, complex macromolecule that has been studied in detail and represents one of the most remarkable nanomachines discovered to date. Vesicles containing specific proteins or other fragments tend to be associated with the endoplasmic reticulum from where they rise from the membrane wall in serial buddings.

Other relatively independent organelles include lysosomes which are primarily concerned with the dismantling and recycling of intracellular materials including the membranes of old organelles. They contain an acidic interior necessary for reducing proteins to peptides and amino acids. Peroxisomes reduce fatty acids and play a role in neutralizing intracellular toxins. Secretory vesicles are another unique organelle that contain proteins secreted from a variety of sources and act as packaging material during transit to a distant site. They can fuse with the cell membrane or with some organelle membranes, allowing them to release the proteins they have stored. Another membrane structure of the cell that is considered an organelle is the microvilli. They represent an elegant adaptation that greatly increases the absorption area of the cell membranes. Almost the entire small intestine is lined with endothelial cells known as enterocytes on which the absorptive surface is completely covered with microvilli. The surface areas of the cells are literally studded with these little finger-like projections, much like the fibers of a carpet. They increase the surface area of the absorptive area many times over.

In the past, intracellular distribution was thought to occur primarily by passive diffusion. We now know that there is a very special, precise, and well-organized method for distributing proteins and secretions. We now recognize that at least three specific transport systems operate primarily in all living cells: (1) secure transport, (2) transmembrane transport, (3) vesicular transport.

- Secure transport refers to the passage of molecules through the pores of the nuclear membrane simulating passage through an open door.

- Transmembrane transport takes place mainly between membranous organelles and the surrounding cytosol by means of an active transport system.

- Vesicular transport is rather spectacular in that it is an active transport of vesicles of different sizes, carried or pulled by a family of motor proteins. These are large macromolecules with coupled tube-like projections that ‘advance’ along microtubules. They can adjust their pace depending on size and load. These macromolecular transport motors represent another recently discovered nanomachine that

is widely distributed throughout the animal kingdom.

The discovery of these intracellular transport systems above has transformed the perception of intracellular dynamics from a relatively quiet, inactive, slow-moving medium to one that is much more like a super highway on which loads of various shapes and sizes are transported here and there at high speed while these same highways are simultaneously dismantled and new ones are built.

¶ Macromolecular Protein Motes

There is a family of macromolecular protein motors that are widely distributed throughout animal cells and are used extensively for intracellular transport. They primarily move vesicles but also transport organelles and proteins within cells. The original classical studies of this phenomenon were performed on giant squid axons. Giant squid axons provide an almost ideal model for experimental research on intracellular transport because they are large, 100 times the width of an average mammalian axon, and they are accessible. Because of its great length, the transport cell plays a major role, transporting proteins and other essential things such as organelles, synthesized in the cell body, to the end of the axon. Kinesin-1 was the motor protein initially identified and studied. It moves in one direction, always toward the plus end of the microtubule. Microtubules each have a plus end and a minus end. In cells, they are oriented like the spokes of a wheel, radiating from the centrosome which functions as a microtubule organizing center (MTOC). The minus ends are oriented toward the center while the plus ends are oriented toward the periphery.

The kinesin-1 motor moves in steps, using ATP as its energy source. Its maximum speed is three microns per second or about 250 mm per day. (15) At this speed it would take about four days to travel the length of the longest human axons that extend from the neuronal cell body in the lower spinal cord to the nerve that ends in the big toe. At its maximum speed, its ‘steps’ are 16 nm. The protein motor, at its maximum speed, averages 375 steps per minute. That’s a fast pace any way you count!

Another widely recognized but less well understood protein motor than kinesin-1 is dynein. It is a negative-oriented protein motor, so it moves in the opposite direction on microtubules. When protein motors reach their destination; in this case, the minus end of the microtubule, because they are unidirectional, they must be passively transported down the microtubule, back to their starting point. The exact way protein motors are turned on or off is not known. Motors can operate at a variety of speeds. The speed appears to depend on the size of the load. For example, the transport speed of a mitochondrion is moderate. The slowest transport speeds that have been measured are on the order of a few millimeters per day.

A third family of protein motors is known as myosins. Of the 20 members of this family, three are important in humans. Myosin I is a single-headed molecule associated with membranes and functions largely in endocytosis, providing the mechanical force to constrict the cell wall during cell division. Myosin V is two-headed, functioning primarily in the transport of organelles within cells. Myosin II is probably the most widespread and is responsible for providing the force for contraction in muscles, including striated muscle, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle. The mechanically active portion of the molecules is confined to the head and neck domains and is powered by ATP. More remarkable than the mechanical force produced by myosin activity is the astonishing neural control and coordination of muscle groups that is characteristic of all voluntary muscle function. One can hardly watch an Olympic athlete or a ballet dancer without experiencing a thrill of inspiration. The most astonishing muscular activity is that demonstrated by the human heart which begins to beat around the 6th or 7th week of gestation. The same muscle cells responsible for those very first heartbeats will function continuously throughout life, beating approximately 37 million times a year for 70, 80, 90 or even 100 years for a total of 2.6 to 3.7 billion times, which take place with virtually no awareness or conscious control.

¶ Structure and function of a basic macromolecular nanomachine: ATP synthase

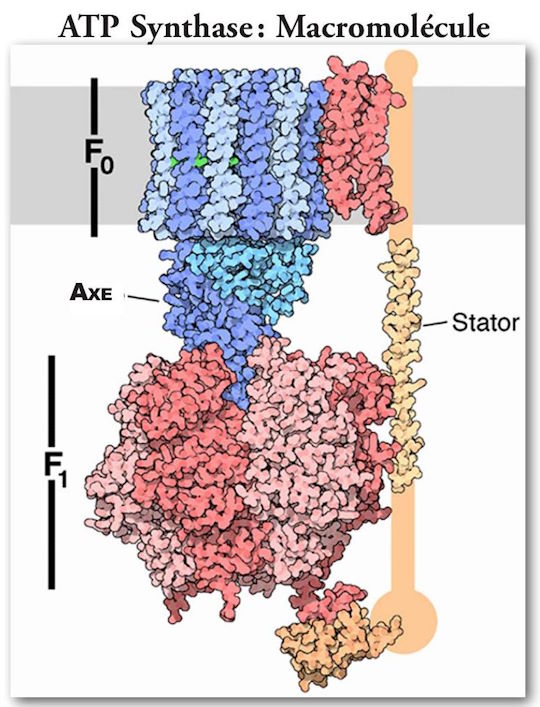

ATP synthase: diagram

(Note: The orientation of Figure 6 is reversed.)

(See Figures 5 and 6.) It is the primary generator of ATP throughout the animal kingdom. It consists of two large multiprotein components, one static, orange, anchored in the mitochondrial membrane, and the other mobile, green, which rotates somewhat like the rotor of a motor. The mobile component is a multiprotein complex consisting (in humans) of 12 identical triangular molecules arranged in a cylindrical configuration. It has a rigidly attached columnar protein structure vertically so that when the cylindrical structure, acting as a rotor, rotates, the column rotates with it like a drive shaft. The cylindrical portion is positioned in the plane of the mitochondrial membrane. Each of the triangular proteins is denoted c. Its rotation is powered by protons flowing, one after the other, along a pathway consisting of two half-channels leading from the exoplasmic medium, passing through the mitochondrial wall, and emptying into the inner cytosolic medium. Since it takes one proton to turn the rotor of one c-unit, in humans it takes twelve protons to provide one complete rotation.

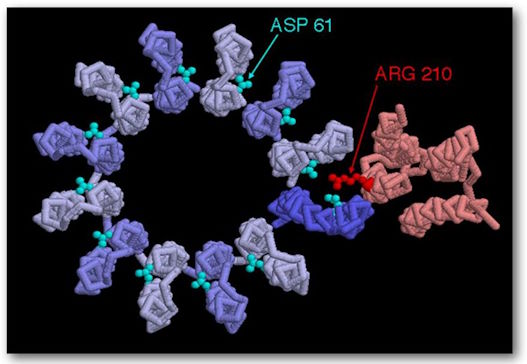

ATP Synthase, structure, F0 top view, showing positions 210 on the amino acid and positions 61 on the amino acid aspartate. They represent the binding sites.

As a proton passes through the first half-channel, about halfway down the wall, it interacts with Asp (aspartic acid)61 at its proton-free binding site, resulting in a negative charge being balanced on that side of the amino acid. It is also partially balanced by a positive charge on Arg (arginine) 210. "The proton fills the empty proton-binding site and at the same time displaces Arg 210 from the side chain, which swings sideways to the adjacent proton-filled binding site on the adjacent c-subunit. As a result, the proton bound to that adjacent site is displaced. The adjacent displaced proton moves along half-channel II and is released into the cytosolic space by giving up an empty proton binding site on Asp 61. A levorotatory rotation of the entire c-circle moves the “empty” c-subunit into half-channel I. (16) The rotation is caused by thermal/Brownian motion and all of this is powered by the “proton motive force” across the membrane which drives the flow of protons across this membrane from the exoplasmic medium to the cytosolic medium.

As mentioned earlier, there is a static component that is actually larger in size than the rotating component. It is just over 100 nm in diameter. It is firmly anchored to the mitochondrial membrane. There are two large pairs of linear structures, with an additional protein macromolecule intervening and supporting a large torus-shaped structure, which consists of three alternating pairs of macromolecules. These structures are located at the top of the rotor axis described earlier, much like the cap of a mushroom, is located on the tail of the mushroom.

The three pairs of large molecules, called alpha and beta, form the structure of the hat, and occupy 120º each of the 360º circle. There is an asymmetric molecule attached firmly to the upper end of the rotating axis. This structure functions like a cam. As the cam rotates, at each 120º segment of the turn it comes into intimate contact with the binding sites of each of the three pairs of macromolecules, causing a change in conformational state in each. There is an actual change in the shape of the protein structures which causes a change in each of the binding sites.

As it rotates, it passes through each of three stages at the binding sites. The first stage is the release of an ATP molecule; the second stage is the weak attraction of an ADP + Pi molecule; and the third stage is a strong attraction of ADP + Pi resulting in a tightly bound ATP molecule, ready for release into the cytosolic milieu in the next cycle.

The rotation rate has been experimentally measured to be about 134 revolutions per second. The rate of generation of ATP molecules has been experimentally measured to be about 400 molecules per second. Since three ATP molecules are produced and released into the cytosolic medium with each rotation, these values agree very well. Well-recognized ‘feedback’ systems that control the rate of synthesis are recognized such as the concentration of ADP. There is also a coupling of the oxidation of NADH and FADH2 to ATP synthesis, so that if the resulting proton motive force is not dissipated during ATP synthesis, the transmembrane resistance gradient will increase and eventually block further reaction.

To summarize, ATP synthase is a large macromolecular nanomachine that performs one of the most critical functions in the kingdom of bacteria, animal and plant. It is an essential component of almost all living cells. It generates the fuel required to run all major physiological functions of living organisms.

It is formed of twenty-five distinct macromolecules of which five are solitary, four are paired, and one is made of twelve identical copies arranged in a complex cylindrical protein that acts as a rotor rotating at an experimentally determined speed of 134 revolutions per second (8040 revolutions per minute). It is uniquely located in the wall of mitochondria and provides a passage for protons to flow across the membrane through two uniquely arranged half-channels, driven by the proton motive force. (16)

It is estimated that in humans the amount of ATP produced and used each day is approximately equal to the total body weight. Without ATP all animal life would cease immediately. In fact, the sodium-potassium pump, responsible for maintaining the relatively negative sodium and relatively positive potassium concentration in all cells, an essential condition for all cells, is totally dependent on ATP as an energy source. How can one conceive that an irreducibly complex macromolecular nanomachine such as ATP synthase, which is absolutely essential to life, could possibly evolve when the evolutionary process based on chance mutations and the survival of the fittest, depends on the processes of life itself that could not take place without this very remarkable nanomachine?

Recommended as a follow-up to this presentation is the highly accurate animated video depicting intracellular molecular activity, produced at Harvard and distributed on YouTube, entitled ‘Inner Life of the Cell’. It can be found at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wJyUtbn005Y

¶ Conclusion

What characterizes living molecules? The elements do not differ whether they compose an organic or inorganic cell. They appear identical and interchangeable. The obvious characteristic of the elements composing living cells is that they perform functions in an organized way. For example, digestive enzymes break down ingested food into absorbable component parts that are necessary to sustain life. These components are then absorbed, processed, stored, and distributed as needed. Muscle cells participate in movement and locomotion; myocardial cells pump blood day and night, year after year; red blood cells carry oxygen and carbon dioxide (carbon dioxide); neurons transmit electrical signals to the ends of muscles to initiate locomotion; highly specialized retinal cells transmit visual data along optic nerve pathways to the occipital cortex where visual phenomena are interpreted; Other neural centers in the brain enable self-awareness, awareness of others, and even the contemplation of cosmic consciousness. Because of organization, so many moving parts seem synchronized so that living organisms can function efficiently. Where does this organization come from? How did the incredible density of information become established in the first DNA molecules? How could a cell appear before there were cells?

Given our recently greatly expanded understanding of the complexities of intracellular molecular activity, it is reasonable to ask whether there are any cells that are not irreducibly complex? This is not a denigration of Charles Darwin’s brilliant observations about the interrelationship of all living organisms or a questioning of the fact of evolution. He could not have imagined the intracellular complexities that we have recently discovered. In his day, all this was happening entirely in “a black box.”

Where did this apparent sense of purpose that characterizes so many living organisms come from? The need to obtain food, to grow, to reproduce, to avoid predators, and to protect one’s young? How did the concept of a genetic code arise spontaneously? The encoding of information depends on high-level cognitive thinking.

How did the first cell acquire ATP to operate its sodium-potassium pump that generates and maintains the transmembrane electrical potential that is an absolutely essential component of every living cell? ATP synthase, responsible for generating the ATP required to power most intracellular functions, depends on the proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane for its energy source as well as the electron transport cascade that produces the proton motive force, which provides the energy to generate ATP. How did the large, complex macromolecular ribosomes form when there were no protein factories to produce the polypeptides from which they are made?

Our newly acquired ability to analyze living organisms at the molecular level has opened our eyes to countless nanomachines operating at incredibly high speeds, performing precise actions with astonishing accuracy, actions based on specific instructions from sources encoded in chemical libraries that have reliably preserved and passed down the mysteries of life from generation to generation for hundreds of millions of years. There are so many moving parts! How do they avoid collisions? They seem so connected and so synchronized.

Looking back, we observe a gigantic biological Big Bang around 520 million years ago. Suddenly, many phyla and complex multicellular body plans burst forth into the seascape. The seemingly explosive creative forces of the Cambrian period have since subsided. The tempo suddenly changed and endurance and ingenuity emerged. A long period of sorting, sifting and diversification followed and continues. Diverse life forms can be found with a searching gaze. Now that we Homo sapiens have finally emerged at the top of the food chain and no longer need to spend every waking hour searching for food and providing protection, we have time to think and look around us. We have expanded our vision significantly both inward and outward. What we now see in both directions is absolutely astonishing.

Early in my career we struggled to identify intracellular structures with a light microscope with a resolution of about 1 μm. The electron microscope soon extended this resolution by several orders of magnitude, down to resolutions of a few angstroms. We observed living molecules measured in nanometers. Eukaryotic cells, once thought to be little packets of protein fluid wrapped in pockets of phospholipids, are in fact complex factories filled with millions of nanomachines that scurry around, working at incredible speeds, never taking a break, and performing all maintenance, all repairs, including replacement with new machines, on the fly. And if that factory happens to be an enterocyte lodged in the small intestine, the entire factory will be replaced, on average, every five days.

How many cells, each containing thousands of nanomachines, are there in the average human body that require organization and supervision? Is it 10 trillion or 100 trillion? Both numbers are printed. We don’t really know, but whatever it is is beyond human comprehension. And, to complicate matters further, these factories are not all alike. Each organ has very distinct functions. Red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and carbon dioxide from the body’s tissues to the lungs. White blood cells fight infections, suppress inflammation, and manufacture antibodies against invading viruses. Specialized cells in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas produce insulin, liver cells produce bile, thyroid cells produce thyroxine, the heart contracts and expands as it pumps blood, and neurons interpret visual data, signaling the legs to walk and the cerebral cortical neurons to think. The brain, for example, has hundreds of different subtypes of neurons.

So many moving parts! Flagella spinning at 100,000 revolutions per minute, the ATP synthase motor spinning at 8,000 rpm, producing ATP molecules at the rate of 20,000 per minute, and motor proteins transporting loads at 8 nm per step and 375 steps per minute.

So many moving parts and moving so fast! It’s reminiscent of the experience of watching a ballet. So many movements but all perfectly synchronized with the music, all precisely coordinated and timed. Highly demanding in terms of endurance and stamina, and yet no collisions, no falls and no interruptions.

¶ Where is the choreographer?

Bibliography

- Lodish, H, et.al. Molecular Cell Biology, W H Freeman and Company, New York NY (2013) pp. 544-552.

- Savage, D. F, et al., “Architecture and Selectivity in Aquaporins: 2.5 \AA X-Ray Structure of Aquaporin Z,” P L_{0} S Biology 1, no. 3 (December 22, 2003):doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.

- Shapiro, L, Losick, R, “Protein Localization and Cell Fate In Bacteria,” Science 276 (May 2, 1997): 712 — 18.

- Harold, F M, The Way of the Cell, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England (2001) pp. 65-66.

- Lili, C, “Traditional Theory of Evolution Challenge,” Beijing Review (31 March — 6 April 1977): 10

- Levinton, J, “The Big Bang of Animal Evolution,” Scientific American, (November 1992): 84 — 91; Kerr, R A, “Evolution’s Big Bang Gets Even More Explosive,” Science 621 (1993): 1274 — 75; Monastersky, R, “Siberian Rocks Clock Biological Big Bang” Science News 144 (4 September 1993): 148.

- Gould, S J, Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. New York, N Y (1989) p. 56.

- Chen, J Y, Li, C W, Chien, P, Zhou, and Gao, F, “Weng’an Biota-A Light Casting on the Precambrian World” paper presented to the origin of animal body plans and their fossil records, China 20 — 26, June 1999.

- Lili, C, Chen, J Y, Zhou, G Q, Zhu, M Y, Yeh, K Y, The Chengjiang Biota: A Unique Window of the Cambrian Explosion, volume 10.

- Gearty, W. “The Cambrian Explosion: Evolution’s Big Bang,” Yale Scientific, 23:37 (December 23, 2013).

- Lee, M.S.Y., et al., “Rates of Phenotypic and Genetic Evolution during the Cambrian Explosion, Current Biology, 23: 19, (October 7, 2013) pp. 1889 -1895.

- Gould, S J, Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. New York, N Y (1989) p. 57

- Lodish, H, et.al, Molecular Cell Biology, W H Freedman and Company, New York, NY (2013) page 988-89.

- Krimm, Samuel; Bandekar, J. (1986). “Vibrational Spectroscopy and Confirmation of Peptides, Polypeptides, and Proteins”. Advances in Protein Chemistry. Advances in Protein Chemistry 38 ©: 181 — 364.

- Lodish, H, et.al, Molecular Cell Biology, W H Freeman and Company, New York, NY (2013) p. 833.

- Lodish, H, et.al, Molecular Cell Biology, W H Freedman and Company, New York, NY (2013) p. 547.