© 1996 Wayne and Ute Ferrier

© 1996 The Fellowship for readers of The Urantia Book

| In Close Proximity — The World of the Nonbreathers | Winter 1996 — Vol. 6 No. 8 — Index | Study Groups of Tennessee |

By Wayne and Ute Ferrier

Berkshire, New York

You introduce a friend to the Big Blue Book and one of their first questions is, “Urantia, what does that mean?” You say, “Urantia is the name of our world.” Often your friend’s inquisitiveness is satisfied.

Many longtime readers assume that the word Urantia came into use by humankind in the 1930s when The Urantia Book was written.

Actually if dictionaries were to list the word and its origin, Urantia can be traced at least as far back as the Sumerian era of languages some 5,000 years ago. That is old for a word. Roughly 5,000 years ago is about as far back as archaeologists have been able to track human civilization through artifacts like written records.

While we have other artifacts much older than that, it has been the writings that have given historians the most insight into how ancient societies were structured and what beliefs they held. Many of these records can be found in universities or libraries; for example, the clay tablet (from around 2000 B.C.) recounting the Sumerian flood story is in the custody of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

¶ The Nodites

According to The Urantia Book, the Nodites go back 200,000 years. The Nodites were the ancestors of the Sumerians, from whom the western world inherited mathematics, astronomy, law, government, trade, art and a history veiled in mythology. The Nodites were the descendants of Caligastia’s staff who have been described in the Bible as the “giants of old,” and these giants were our cultural forefathers.

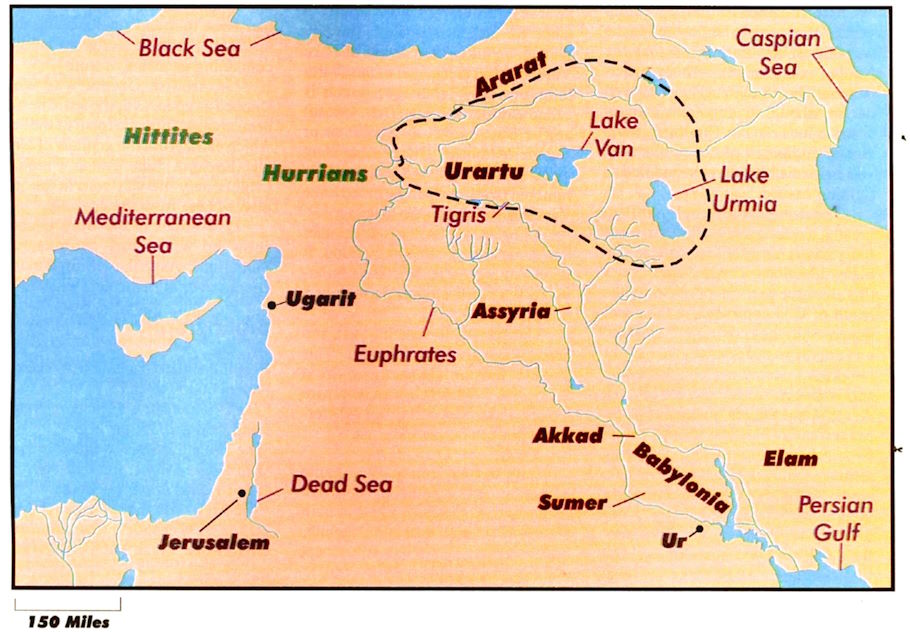

Many Nodites took the side of the insurgents during the rebellion, but some left their leader Nod and joined in with Van, who had steadfastly refused to align himself with the fallen Planetary Prince. These Vanites settled in the Ararat region of Anatolia, what is now eastern Turkey.

The Ancient Near and Middle East

The Nodites were also the builders of the tower of Babel. About 50,000 years after the death of Nod, the Nodites decided to do something in order to preserve their racial unity.[1] It is ironic that the project they decided on for this purpose ended up dividing the Nodite race.

In a council meeting of the tribes the plan of Bablot, a descendant of Nod, was accepted. Bablot was the architect and builder of the tower that was to glorify the Nodite race and the project was hence named after him.

The Nodites, however, were divided about what purpose the city of Bablod and its tower should have. The largest group wanted the tower as a memorial of Nodite superiority and to challenge future generations. The next largest faction wanted Bablod to preserve Dilmun culture and thought it would make a great center for commerce, art and manufacture.

The third and smallest group wanted the tower to be devoted to the worship of the Father, so that the Nodites could atone for their participation in the rebellion. They believed the city should function as a cultural and religious center. This third group, mostly composed of noncombatants, was immediately outvoted and fled as fighting ensued.

The tower of Babel conflict greatly reduced the Nodite race and the remaining peoples scattered in many directions. The Bible describes this disagreement of purpose as the result of God confounding their languages until they couldn’t understand one another’s speech.[2]

The descendants of the Nodite survivors split into three groups: the Assyrians, the Elamites and the Sumerians. These three groups retained a common written language, although they went their separate ways. At times they competed over dominion of certain areas.

The Assyrians, descendants from the western or Syrian Nodites, were the largest group of the three and ruled over the Babylonians. The eastern or Elamite Nodites, who later greatly blended with the Adamites, settled primarily in Iran. The central or pre-Sumerian Nodites, the smallest group of the three, remained fairly pure for thousands of years before blending with the Adamites and becoming the Sumerians.[3] The way modern day historians and archaeologists see it, it was from these Sumerians, who lived at the mouth of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (near Ur) 5,000 ago, that civilization emerged.

¶ The Land of Urartu

About 50,000 years before the tower of Babel conflict a group of Nodites separated from their leader Nod to follow Van and Amadon. This group known variously as northern Nodites, Amadonites or Vanites, settled around Lake Van in the Ararat region. In this region, Adamson founded the center of his civilization about 37,000 years ago. Mount Ararat became the sacred mountain of northern Mesopotamia.[4]

While Ararat today is the name of a particular mountain, it was known in pre-history as a region. The word Ararat is a derivation of Urartu, a name for ancient Armenia. The city of Van, on the eastern shores of Lake Van, was the chief center of the Urartu kingdom. The language spoken is called Urartian (coming from Urartu) and is also known as Chaldean or Vannic. Although Urartian has long since been considered extinct, it is rumored that some people in the Lake Van area still speak the language.

Urartian is related to all the other languages of that time and region. It seems unlikely that the close similarity to the word Urantia is merely a coincidence.

German historian, linguist and author Johannes Friedrich wrote in his book, Extinct Languages, how Sumerian, Urartian and Elamite words, though often spoken differently, have the same meaning:

“The spoken word may sound quite different in Sumerian and in Akkadian, in given cases also in Hittite, Hurrian, Urartian or Elamite, but the written symbol of the concept is identical in all these languages.” [5]

These ancient languages were not confined to Urartu and they permeated into neighboring regions. Mesopotamia, which had no natural boundaries, was eventually absorbed into other empires. Friedrich mentions that the clay tablets of cuneiform writing from Babylonia spread into remote parts of the Near East, Syria, Asia Minor and Minoa of prehistoric Greece. Since cuneiform writings are some of our oldest surviving records of written language, historians have been understandably intrigued, but according to The Urantia Book, the peculiar form of cuneiform writing evolved after the alphabet of Dalamatia had been lost.[6]

From this early center of Sumerian civilization, ideas and knowledge were exchanged on the trade routes along with commercial transactions.

Historian J.C. Margueron concluded that since Mesopotamia greatly influenced the Greeks, we ought to think of Mesopotamia as the cradle of western civilization. It was the Mesopotamian world that produced the first great civilization and bestowed its benefits on neighbors.[7]

Stories from Dalamatia and Eden had been told and retold, being distorted after thousands of years, but still containing elements of truth.

Aphrodite Urania was worshipped as goddess of the sea. She had been created from the foam of the sea, which came from the genitals of Uranus (heaven). Like Urania, Urantia’s evolutionary life was born in the sea, planted here from the heavens.

Derivations of the word Urantia show up with many peoples, the Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks and, in particular, Vanites.

¶ Bibliography

Recommended Urantia Book reading: Papers 66 to Paper 78.

| In Close Proximity — The World of the Nonbreathers | Winter 1996 — Vol. 6 No. 8 — Index | Study Groups of Tennessee |

¶ Notes

The Urantia Book. Chicago: Urantia Foundation, 1955; UB 77:3.1. ↩︎

The Bible. Genesis, chapter 11. ↩︎

The Urantia Book; UB 77:4.10. ↩︎

Friedrich, Johannes. Extinct Languages. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press Publishers, 1957; pg. 37-38. ↩︎

Margueron, Jean-Claude. Mesopotamia. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1965; pg. 180. ↩︎