© 1961 William S. Sadler Jr.

© 1968 Urantia Foundation

So far in our study we have been voyaging outward from Havona, through the superuniverses and into the outer space levels, without giving too much thought to how big they are in space or how long these adventures are going to take in time. It may be a good idea to pause, at this point, long enough to consider the size and duration of the master universe. How big is it? How massive is it? How long do the universe ages last in time?

¶ § 1. Space Magnitudes of the Master Universe

We know the seven superuniverses are much larger in space than the central universe. Havona contains one billion (and 21) worlds and the plans for the superuniverses provide for seven trillion inhabited worlds. We do not know exactly how big Havona is, but we do know that Orvonton (our superuniverse) is about one-half million light-years across. If we ignore Havona, then we could estimate the grand universe is about one million light-years across.

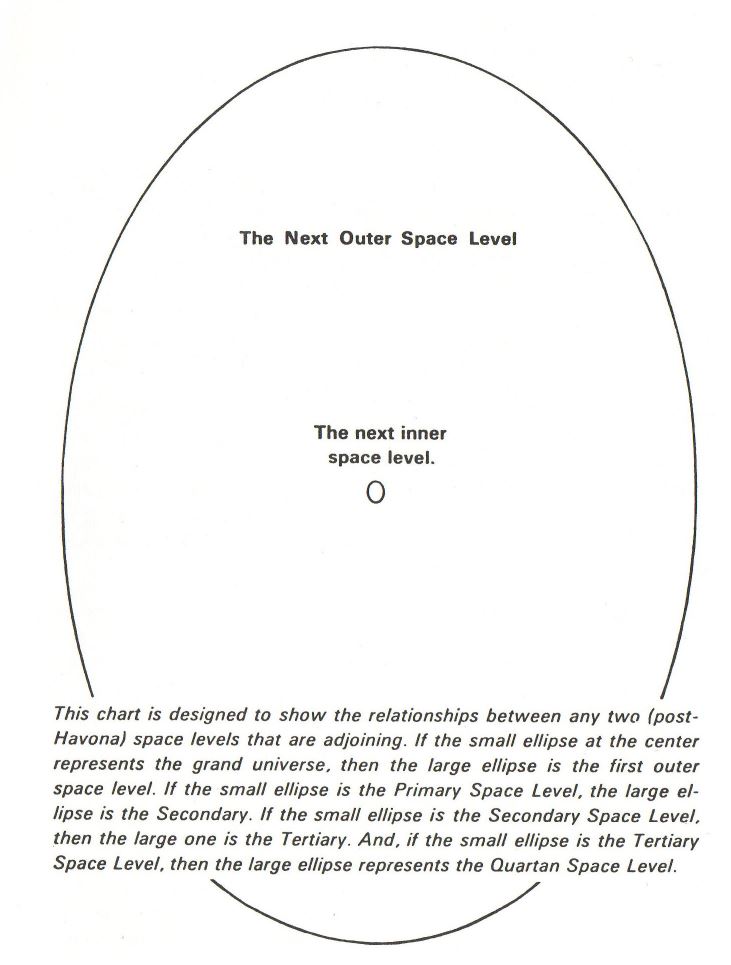

Now, we are shortly going to encounter some sizes that are very much greater than that of the grand universe. This means we will have to symbolize the size of the grand universe by likening it to a tennis ball. We can then compare it to the Primary Space Level, if we compare the tennis ball to a rather large living room. This means the first outer space level is ever so much larger than the whole of the present organized and inhabited creation.

We have symbolized the comparative size of the grand universe and the first outer space level. What is the comparison in size between the Primary and the Secondary Space Level? This can be expressed by comparing our sizeable living room with a rather long city block. First think of this city block as a cube, then think of the living room as being suspended in the center of this cube. We are now thinking of how the Primary Space Level fits inside the Secondary Space Level. These comparisons should help us to develop something of a “feeling” for the great increases in the size of the space levels as we proceed outward.

How about the Tertiary Space Level? How big is it? Well, on the scale that we have been using it would be symbolized by a rather large city – or, rather, by the cube of a large city. Think of a cube that is 32 miles by 32 miles square, and then is 32 miles high. This cube gives us the relative size of the Tertiary Space Level.

The Quartan Space Level is, by far, the largest of all. If the diameter of our moon were about one-half larger, then the moon would serve as an ideal symbol for the size of this final space level. (The moon is 2100 miles in diameter and the symbol for the Quartan Space Level should be 3200 miles in diameter.) We will use the moon as a symbol, anyway.

Now, to get a real feeling for the increases in size (as we proceed outward from the grand universe to the edge of the master universe) let us start with the tennis ball. Let it float in the center of the large living room; suspend the living room in the center of the large city block (the block that we have pictured as a cube); picture the cubic city block floating at the center of the cubic city (the cube that is 32 miles long on each edge); and then, finally, float the cube of the big city in the middle of our moon. Now go back and think about the tennis ball; it symbolizes the size of the grand universe – the presently organized and inhabited creations consisting of Havona, plus the seven superuniverses, with their 700,000 local universes and seven trillion inhabited worlds.

Think about the tennis ball – then think about the moon.

¶ § 2. Mass Magnitudes of the Master Universe

We have less information about the probable physical mass of the master universe than we have about its size in space. But we do know the physical masses in outer space are very much greater than anything known in the grand universe.

We are informed that there are at least 70,000 aggregations of matter in outer space and each one of these is already larger than a superuniverse. In another passage in the Papers we are told our astronomers will soon be able to see 375 million new galaxies in outer space. Whether these two statements refer to the same physical creations or not, we do not know. But we believe that they do, and that all of these large masses are in the Primary Space Level.

We also know that most of the drawing power of Paradise gravity is absorbed in exercising control over these outer space creations. These universes of the future are now just getting started; they are going to continue to grow for a very long time.

What little we do know about the physical materialization of the outer universes seems to support the idea that the outer space creations are very much greater in space-size and physical-mass than is the grand universe.

¶ § 3. Time Magnitude of the Master Universe

The calculations of the length of the universe ages take us into numbers that are awkward because they are so very large. We normally reckon time in years. This can become difficult, as difficult as it would be to figure astronomic distances in miles, instead of light-years. Suppose we work out a convenient unit for measuring time – such as the light-year is used for measuring distance – some unit that takes in a lot of time. We might take the age of the Andronover nebula (about a trillion years) as such a useful time unit. We could then express the estimated length of the universe ages in terms of “Andronover Time Units.” We could even abbreviate this as “ATU” for one unit, and as “ATUs” for more than one.

In terms of “ATUs” the universe ages can be calculated as having the following time spans:

- The second age – 50 thousand ATUs

- The third age – 5 million ATUs

- The fourth age – 500 million ATUs

- The fifth age – 50 billion ATUs

- The sixth age – 5 trillion ATUs

In selecting “Andronover Time Units” (about a trillion years) we are selecting the longest time-span that is mentioned in the Papers – the age of Andronover, the nebula that gave birth to our sun. The numbers tabulated simply tell us how many times longer the universe ages are than the age of Andronover.

We have calculated that it is possible the Second Universe Age, the present age, may be as much as three-fourths completed. Even so, there remains approximately one-fourth of the present age; this is more than 10,000 ATUs, more than 10,000 trillions of years. We still have ample time to reach Paradise!

(For general references to Papers, and for the reasoning and the mathematics which support the findings presented in this chapter, see: Appendix XVI., Physical Magnitudes of the Master Universe; and Appendix XVII., Time Magnitudes of the Master Universe.)