[ p. 186 ]

CLOSE OF THE THIRD INTERGLACIAL. TEMPERATE, AND ARID CLIMATE. ACHEULEAN INDUSTRY — ADVENT OF THE FOURTH GLACIATION, PROFOUND CHANGES IN ANIMAL AND PLANT LIFE — THE ARCTIC TUNDRA PERIOD OF MAMMALIAN AND PLANT LIFE — CHARACTERS OF THE NEANDERTHAL RACE, OF THEIR MOUSTERIAN FLINT INDUSTRY — SUPPOSED CAUSES OF EXTINCTION OR DISPERSAL

We now reach a prolonged and important stage in the prehistory of Europe, namely, the period of the fourth glaciation, of the final development of the Neanderthal race of man, of the Mousterian industry, of the beginnings of cave life, of the chase of the reindeer, and its use for food and clothing.

In all Europe the Acheulean industry appears to have come to a close during a period of arid climate, warm in some parts of western Europe and cool or even cold in others. The seasonal variations may well have been extreme, as on the steppes of southern Russia, where exceedingly hot summers may be followed by intensely cold winters, with high winds and snow-storms destructive of life.

It is this seasonal alternation, as well as the recurrence, either seasonal or secular, of nulder climate, which explains the survival or return of the Asiatic fauna even after the close of the Acheulean industry and when the Mousterian industry was well advanced.

From deposits found at Grimaldi, in the Grotte des Enfants and in the Grotte du Prince, it has long been said that men of early Mousterian times lived contemporary with the hippopotamus, the straight-tusked elephant, and Merck’s rhinoceros in the genial climate of the Mediterranean Riviera. More recently the same animals have been found as far north as the Somme valley in the ‘river-drifts’ of Montieres-les-Amiens.1 Here, again, we find remains 186 [ p. 187 ] of the hippopotamus, the stright-tusked elephant, and its companion, Merck’s rhinoceros, in Mousterian deposits, a suipnising discovery, because it had always been supposed that a cold climatic period had set in all over western Europe even before the close of the Acheulean culture. But there is also evidence of a temperate climate still prevailing in the Thames valley in the period of the Mousterian ‘floors.’ 2 Again, along the Vézère valley, Dordogne, we find that at the station of La Micoque, where the industry marks the transition between late Acheulean and early Mousterian times, Merck’s rhinoceros is found in the lowest layers associated with remains of the moose (Alces).

There is evidence that Merck’s rhinoceros and. the straight-tusked elephant lingered in western Europe during the whole period of the early development of the Mousterian industry. As observed above, these animals were hardier than the southern mammoth, which was the first of the Asiatic mammals to disappear, soon to be followed by its companion, the hippopotamus. Even after the advent of the closely associated tundra pair, the woolly mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros, Merck’s rhinoceros persists, as, for example, in the deposits of Rixdorf, near Berlin, where this ancient tjpe occurs in the same deposits with the woolly mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the reindeer, and the musk-ox, as well as with the forest forms, the moose, stag, wolf, and forest horse. The extreme northern latitude of this deposit explains the absence of the straight-tusked elephant, which may at the time have been living farther to the south. The same mingling of south and north Asiatic mammals is found at Steinheim, in the valley of the Murr, some degrees to the west and south of Rixdorf, not far from Göttingen, where we find Merck’s rhinoceros® and the straight-tusked elephant in association with the woolly mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the giant deer, and the reindeer.

Thus the Neanderthal races were entering the Mousterian stage of culture during the close of the Third Interglacial Stage and during the early period of the advance of the ice-fields from the great centres in Scandinawa and the Alps. As these ice-fields [ p. 188 ] slowly approached each other from the north and from the south a very great period of time must have elapsed during which all the south Asiatic mammals abandoned western Europe or became extinct, with the exception of the lions and hyaenas, winch became well fitted to the very severe climate that prevailed over Europe during the fourth glaciation, and even during the long Postglacial Stage which ensued. The large carnivora readily become thoroughly adapted to cold climates, as they subsist on animal life wherever it may be found; tigers of the same stock as those of India have been found as far north as the river Lena, in latitude 52° 25’, where the climate is colder than that of Petrograd or of Stockholm, while the lion throve in the cold atmosphere of the upper Atlas range. Thus the cave-lion (Felis leo spelaea) and the cave-hysena (H. crocuta spelaea) doubtless evolved an undercoating of fur as well as an overcoating of long hair, like the tundra mammals. In size the lion of this period in France often equalled and sometimes surpassed its existing relatives, the African and west Asiatic lion; it frequently figures in the art of the Upper Palaeolithic artists and survived in western Europe to the very close of Upper Palaeolithic times.

¶ The Fourth Glaciation

Penck4 has estimated that the first maximum of the fourth glaciation in the Alps was reached 40,000 years ago, and that after the recession period the second maximum ended not less than 20,000 years ago. This would extend the Mousterian industry over a very long period of time, for there can be no doubt that the Mousterian culture was practically contemporaneous with the fourth glaciation, even if a briefer period of time should be allotted to this great natural event.

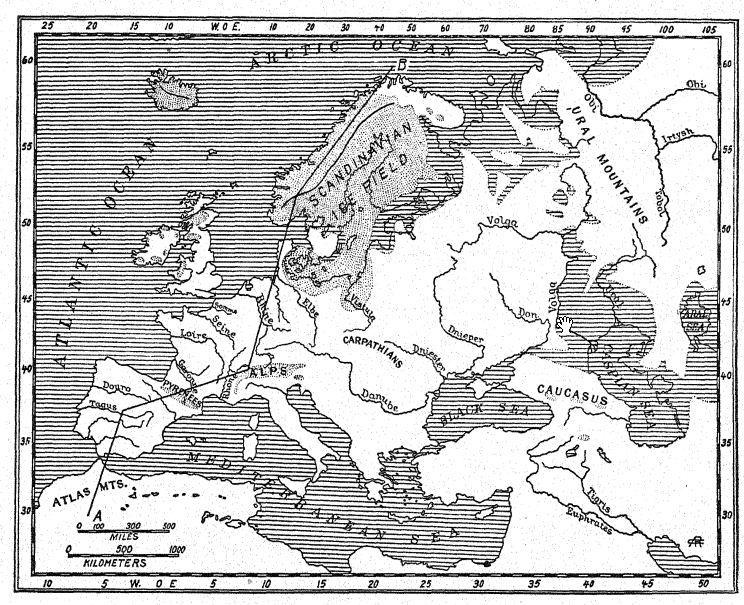

The fourth glaciation, like the first, is believed to have been contemporaneous in Europe and North America, 5 a fact which is of especial importance to American anthropologists in connection with the question of the date of arrival of primitive man in America. In both countries the glaciation reached an early [ p. 189 ] maximum, which was followed by a period of recession of the ice-fields, a time during which a somewhat more temperate climate prevailed, but this in turn gave way to a second advance of as great severity as the first.[1]

In the north, Scandinavia and Finland were again enshrouded in ice, and a great mer de glace occupied the basin of the Baltic Sea, sending its terminal moraines into Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein [ p. 190 ] and over the northern provinces of Germany, but this great ice-field did not again become confluent with that of Great Britain.7 At the commencement of the fourth glaciation large glaciers descended over the Scottish mountain valleys and filled many of them even to the sea; the coast subsided at least 130 feet in this region. In southern Britain along the valley of the Thames there spread an arctic flora, with the polar willow (Salix polaris) and the dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa) ; an arctic plant [ p. 191 ] bed has also been discovered in the valley of the Lea. Thus the tundra climah extended from the Scottish lowlands to the south of England, the land being bleak and almost treeless.8 This, we believe, was also the period of the arctic flora at Hoxne, Suffolk, and of the arctic plant bed in the valley of the Thames. At this time the valley was frequented by the reindeer, the woolly rhinoceros, and the mammoth, whose remains are entombed in the low-level alluvia swept down from the sides of the valley, so that the remains of this arctic fauna may in places actually overhe those of the more deeply buried and far more ancient warm Asiatic fauna of Chellean times. Like the Somme, the Thames® was then from lo to 25 feet below its present level, the bottom having since silted up with alluvial soil.

This was the period of the deposition of the ‘upper drift’ over the north German lowlands, the Alps, and northern England, also of the early and late Wisconsin, or ‘upper drift,’ which spreads very widely over the Eastern States, from Wisconsin southward and eastward to the latitude of New York. The gravels and sands of some of the ‘lowest terraces’ were also deposited.

¶ Mammalian Life of Mousterian Times

The three successive phases of climate and emdronment surrounding the Neanderthal men during the period of the development of the Mousterian industry, were in descending order as follows :

3. Extreme Cold Climate of the Last Great Glacial Advance. Period of the late Mousterian industry of La Quina. Spread of all the arctic and tundra mammals over western Europe, including the niusk-ox; migrations of the obi and banded lemming of the extreme north. Life and industry of the Neanderthal races, chiefly in the shelters, grottos, and entrances to the caverns.

2. Cold Moist Climate. Period of the middle or ‘full Mousterian’ industry of the Neanderthal races. Appearance of the tundra life, including wellprotected mammals and birds from the arctic region, also descent of the Alpine types to the foot-hills and river borders. First forerunners of the steppe life; the full Eurasiatic forest and field life widely spread over [ p. 192 ] Europe. Life and industry chiefly in the shelters, grottos, and entrances to the caverns. Reindeer very abundant.

1. Warm or Cool Arid Climate. Transition from the Acheulean to the early Mousterian culture, as observed in the stations of La Micoque and of Combe-Capelle. The so-called ‘warm Mousterian’ fauna, including the survirdng hippopotamus, Merck’s rhinoceros, and the straight-tusked elephant in northern and southern France; herds of bison, cattle, and wild horses in southwestern France. Tribal life, with the industry partly in open stations, partly under sheltering cliffs.

This is the beginning of the ‘Reindeer Period,’ for this migrant from Scandinavia, with its companions of the northeastern tundras, the woolly mammoth and the rhinoceros, wandered slowly southward before the advancing Scandinavian ice-fields, which were greatly augmented by the increasiilgly cold and moist climate. Thus these animals are found in the north with flints of the Mousterian culture before they appear in the more genial region of Dordogne. In the somewhat older AcheuleanMousterian station of La Micoque, along the V&ztre, the firehearths contain almost exclusively the remains of horses and relatively few remains of bison and wild cattle, but no reindeer. A fireplace near the station of Combe-Capelle yields numerous remains of the bison, only a few of the horse, and the first of the reindeer. Before the appearance of the reindeer in the valley of the Vézère we may picture the meadow-lands as covered with bison and wild horses, the latter of the type which is now characteristic of the high plateaus of central Asia, while the bison of the period appears to be more similar to the American buffalo than to the surviving European form.

Gradually the tundra animals spread toward the south with the cold climate which for the first time swept all over western Europe. The whole aspect of the country slowly changed with the approach of the reindeer, and the northern flora of the spruce, the fir, and the arctic willow clad the more sheltered river-valleys and hillsides, while the plateaus and fields were partly or wholly deforested.

Thus the country became adapted chiefly to the tundra types of mammals ; and in the middle Mousterian strata these herds, [ p. 193 ] [ p. 194 ] newly migrated from the far north and from the northeastern steppes bordering the Obi River, largely outnumber the steppe forms, which are limited to two or three species. Of these the principal types are the steppe horse, related to the Przewalski horse now living in the desert of Gobi, the steppe suslik (Spermophilus rupescens), and the steppe grouse, or moor-hen. The more characteristic forms of steppe life, such as the saiga antelope, the jerboa, and the kiang, were all later arrivals and did not appear until after the close of the Mousterian industry and the disappearance of the Neanderthal race.

This was due to the fact that the climate surrounding the Neanderthal race in Mousterian times was cold and moist, with heavy rainfalls in summer and snow-storms in winter, a climate thoroughly suited to the arctic timdra mammals with their heavy covering of hair acting as a rain shed and the imdercoating of wool protecting them in the most severe weather.

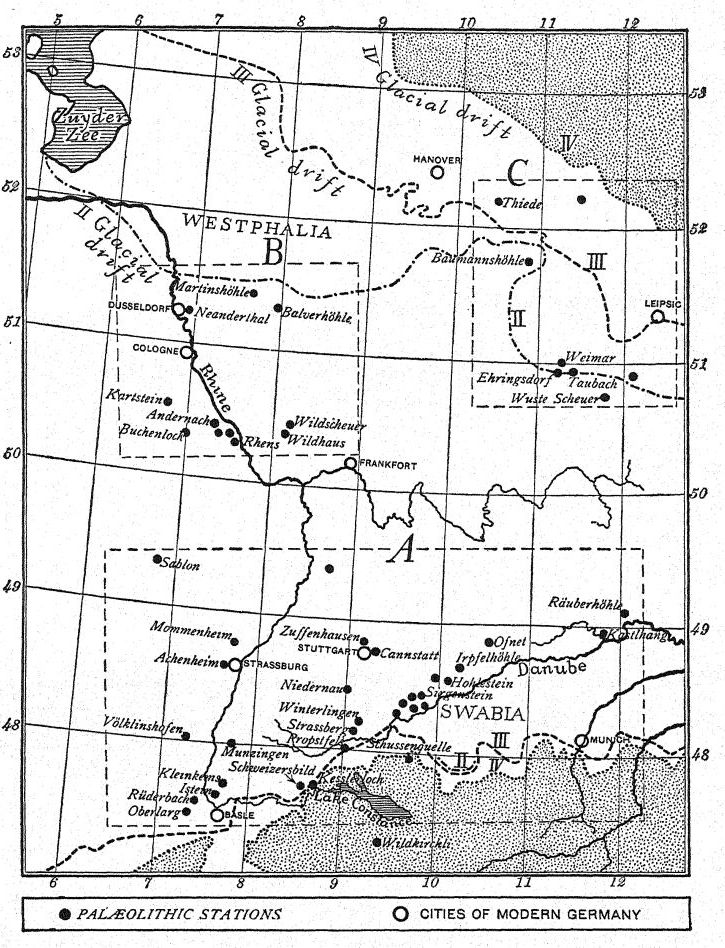

The mammal life during the fourth glaciation, as it spread into the middle Rhine and Westphalian region, is fully recorded in the Toess’ deposits of Achenheim and in the famous grotto of Sirgenstein, on the upper Danube, lying northwest of Munich, where, together with traces of the most primitive Mousterian industry, are found remains of the mammoth, the bison, the reindeer, a species of wild horse, and the cave-bear. Following these mammals there is a record in the same deposit of the arrival of the Obi lemming, from northern Russia.

The fact that only seven Mousterian stations are known in all Germany, or eight if we include the site of the Neanderthal burial, may be accounted for by the relatively close proximity of the great Scandinavian glacier on the north, which was only 350 miles distant from the great Alpine glacier on the south. To the east were the plains of Bohemia and the vast lowland region stretching northeastward to the tundras and eastward to the steppes, through which came the great migrations of tundra and steppe life.

[ p. 195 ]

[ p. 196 ]

¶ Geographic and Climatic Environment of the Neanderthal Race

Let us first glance at Dordogne. Among the stations of the early Mousterian industry we have seen that the Neanderthals in the valley of the Vézère, at La Micoque, were in the midst of a fauna chiefly composed of the bison and of the wild horse, the remains found in the hearths being almost exclusively of the latter animal.[2] In the primitive Mousterian station of CombeCapelle near by the fire-hearths yield remains of the bison but only a few of the horse.

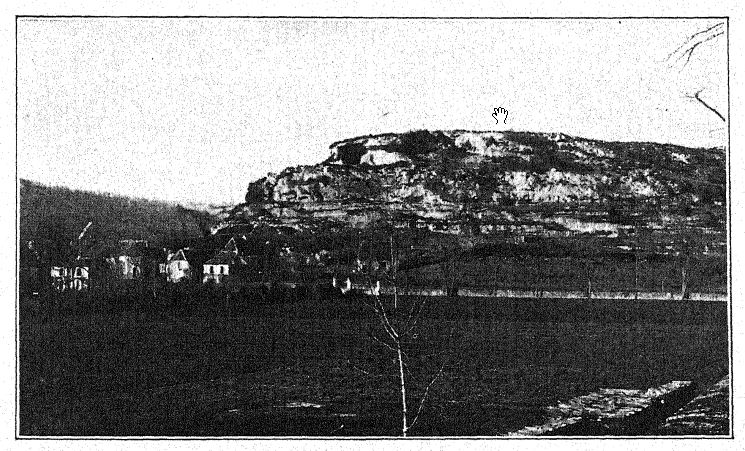

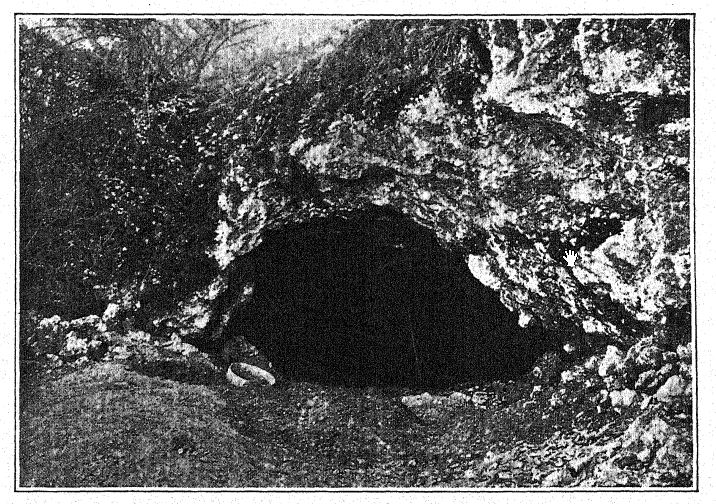

Among the earliest caves inhabited by man10 was that of Le Moustier, situated on the right bank of the Vézère, and about 90 feet above it. This shelter and cave were examined as early as 1860-3 by Lartet11 and Christy and subsequently by de Vibraye,12 Massenat,13 and others. Besides the deposits in the floor of the grotto there, a deep Mousterian culture layer has been found under the cliff in front, and this has been selected for our representation of the life of the men of Mousterian times, and of the flora of the Vfizere in this early period (see frontispiece). Peyrony observes that, here as elsewhere, the older and lower industrial camps were farther away from the shelters; indeed, in this very region there are evidences that the Chellean and Acheulean flint workers occasionally visited the plateaus above; but as time passed and the weather became more severe the Neanderthals began to work nearer to the overhanging cliffs and finally directly beneath them. At this classic station of Le Moustier, one of the most complete skeletons of Neanderthal man was unearthed by Hauser, in 1908. There was a continuous residence here in middle and upper Mousterian times, extending into the lower Aurignacian of the Upper Palaeolithic. The contemporary fauna in these deposits included the mammoth, the reindeer, the giant deer (Megaceros), the horse, the bison, the woolly rhinoceros, and the [ p. 197 ] cave-bear. During the habitation of this typical station by man the climate was very cold and damp.

In this region is found the complete record of the course of Mousterian evolutionyboth in the implements and in the advent of new forms of life; the number of reindeer gradually increases in the ascending layers with the development of the Mousterian industry. There is a constant gradation from the Acheiilean into the Mousterian industrial types; according to Gartailhac, this industry is all the work of the same people, with no sharp lines of division.

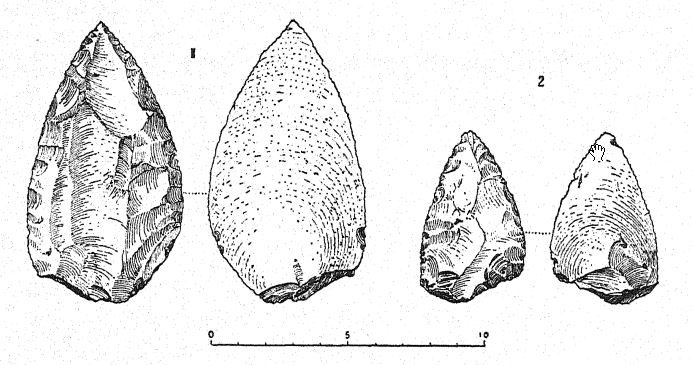

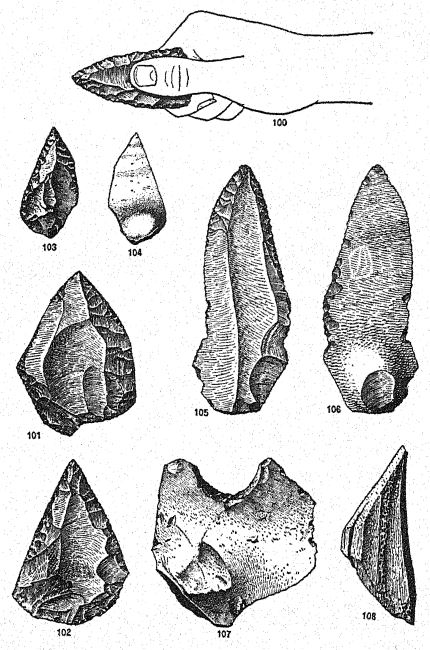

Thus at Combe-Capelle, where the debut of the true Mousterian culture took place, we find a number of large coups de poing, pointing back to the early Acheulean implements. The gradations which are exhibited here in these successive layers are quite in contrast to the advance of the industry at the close of Mousterian times in the very same locality, where there is an abrupt cultural transition toward the Aurignacian.

Southern Britain tells of a similar sequence, which we may interpret as follows. Belonging either to the temperate climate [ p. 198 ] of early Mousterian times, or to the period of the recession of the fourth glaciation, known in the Alps as the Laufenschwankung, are the Mousterian stations along the Lea and near the mouth of the Thames at Crayford (Worthington Smith,14 Geikie15). These Palaeolithic ‘floors’ of Mousterian times are buried beneath 4 to 5 feet of sand and loam and rest upon the surface of older river-gravels. Among the later river deposits several old land surfaces have been discovered ; they consist of a few inches of angular gravel, crowded in places with unabraded implements and flakes which obviously occur just where they were left by Pakolithic workmen. At one point there is evidence that the flint maker squatted over his work, with his knees slightly apart, for the chips are thrown to the right and left in small piles. Here and there, mked with these Mousterian implements, are more archaic forms which may have been drifted down from the older land surfaces above.

[ p. 199 ]

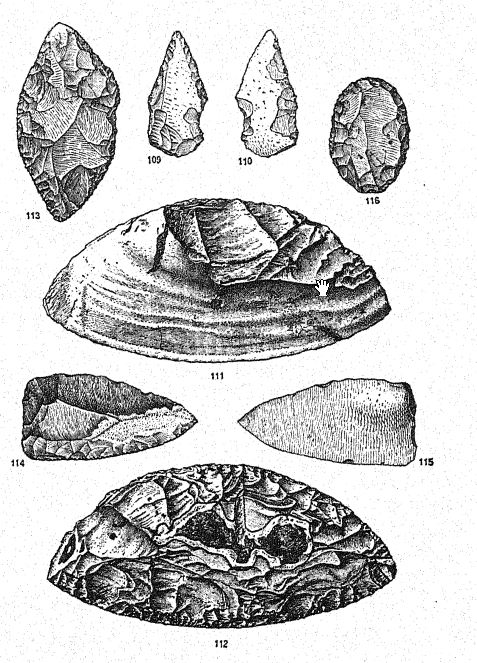

One such floor has been traced by Worthington Smith16 through Middlesex and on both sides of the Thames. Plant remains occur plentifully on this old land surface, including impressions of portions of leaves, stems of grass, rushes, and sedges. The birch, alder, pine, yew, elm, and hazel have been recognized. The common male fern is of frequent occurrence, while the royal fern (Osmunda regalis) is found in profusion. Upon the whole, this assemblage of plants indicates a temperate climate. The flints described and figured by Worthington Smith are either of the late Acheulean ‘Levallois flake’ type or else of early Mousterian age. This writer notes the great number of instruments known as trimmed flakes, which are fomd on the Palaeolithic ‘floor’ ; these are flakes of large size, trimmed to an implement-like form on one side, while the other side is left perfectly plain ; the examples are remarkably constant to one form. The type of implement here described resembles the flakes of Levallois or Combe-Capelle, or even the typical ‘point’ from Le Moustier. Such flakes, shaped into the Mousterian forms of racloir, or scraper, are very common in the gravels of the Lea and of the Thames.

While the remains of the woolly mammoth are found here, there are also indications of the presence of a well-marked temperate flora. These high-level ‘river-drifts’ along the Thames18 were certainly deposited when the climatic conditions were temperate, but they are succeeded by deposits indicating a renewed cold period, which may represent the cold ‘full Mousterian’ times of the Lower Palaeolithic habitation of the Thames. Here we find the remarkable sheets of contorted ‘drift’ attributable to the movements of the frozen soil and subsoil when exposed to the heat of the summer sun. At the same time there may have been deposited along the Thames the alluvial loams and gravels, occasionally containing stones and rocks, which were brought down by ice-rafts ; these low-level gravels are not to be confused with the underlying ‘old river-gravels’ which contain the warm temperate hippopotamus fauna, for they were accumulated under very cold conditions ; they yield remains of the woolly rhinoceros and [ p. 200 ] of the mammoth. Thus, on the high levels of the Thames as well as on the low levels we find evidences of the human culture and of the extinct fauna of the period of the fourth great glaciation.

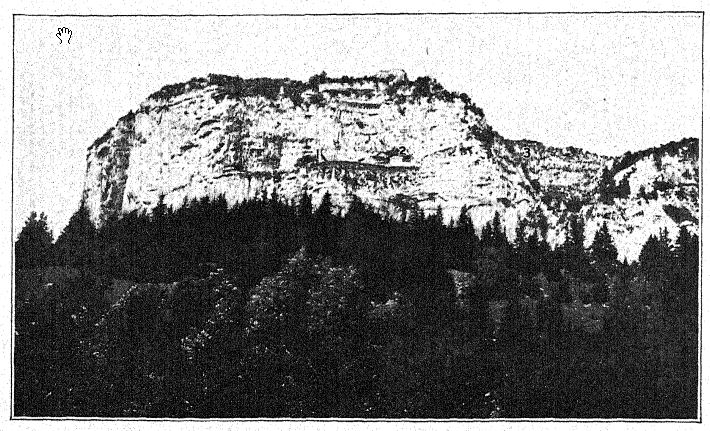

The upper waters of the Rhine and Danube were also frequented by late Acheulean and early Mousterian flint workers. At a point far distant from southern England there is the cavern of Wildkirchli on the Santis Mountains, near Appenzell, in Switzerland ; in Mousterian times this was in the very heart of the north Alpine ice-field. The animal life here may indicate that this cavern was open during the period of recession between the two great advances of the fourth glaciation. Here, at a height of 4,500 feet, Bachler19 between 1903-6, discovered proofs of occupation by Neanderthal man during Mousterian times; the flints are not well formed; the presence of crude bone implements may point to late Mousterian times ; but the flints are considered by Bachler to be of the same stage as those of Le Moustier. It is asserted that when the Neanderthals followed the chase here [ p. 201 ] the climate was more genial, because the animals found include the stag, Alpine wolf (Cyon alpinm fossilis) , cave-bear, cave-lion, cave-leopard (Felis pardus spelaea), badger, marten, and otter, together with the typical Alpine forms, the ibex, chamois, and marmot. But this fauna alone can hardly be taken as proof of a temperate climate, for at this Alpine height we should not expect to discover the tundra life of the period; in fact, it is entirely absent.

Of all the stations along the Danube, by far the most important is that of Sirgenstein, lying between the modern cities of Nuremberg and Augsburg, which was first occupied by the Neanderthals in early Mousterian times and continued to be visited by the Lower and Upper Palaeolithic men until the very close of the [ p. 202 ] Upper Palaeolithic. The continuous section of animal life and of human culture which this remarkable cavern yields afforded Schmidt,20 who began his researches here in the spring of 1906, a key to the prehistory of all the eighteen caverns in the region of the Upper Danube and upper Rhine. In Sirgenstein the primitive Mousterian culture of the early Neanderthals was found, together with remains of the mammoth, bison, reindeer, a species of wild horse, and the cave-bear; this Mousterian industry closed with a record of the arrival in this region of the Obi lemming from northern Russia. Later on the Crô-Magnon race of Aurignacian times left on the floor of the cavern remains of their flint industry and of their feasts, including the bones of the woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, stag, and reindeer. During Upper Palaeolithic Solutrean times the cavern was not occupied ; but early in Magdalenian times it was again inhabited by man, and coincident with his return is the arrival of a great migration of the banded lemming (Myodes torquatus) from the arctic tundras of the north. Finally, toward the end of the Upper Palaeolithic, in late Magdalenian times, another climatic transition is indicated by the appearance of the pika, or tailless hare (Lagomys pusillus). During the Bronze Age this favorite grotto was again entered, and it was also inhabited during a portion of the Iron Age. The d6bris of these various cultures, hearths, and deposits of cave loam reach a total thickness of 8½ feet and mark Sirgenstein as first in rank among the Palaeolithic stations of Germany.

¶ Types and Migrations of the Mammals Hunted by the Neanderthals

This is the life of the period of the fourth glaciation, when a very cold and moist climate prevailed all over western Europe as far south as northern Spain and northern Italy. While the glacial fields were not so extensive as during the third or the second glaciation, the climate was very severe, as indicated by the southward migration not only of the arctic flora but of the mammals and birds of the tundra region bordering the southern shores of the Arctic Ocean. Two or three forms from the cold [ p. 203 ] [ p. 204 ] [ p. 205 ] steppes of northem Russia also found their way into western Europe, but this was distinctly not a steppe period because of the prevailing moisture of the climate ; in place of the westerly winds and great dust clouds of closing Acheulean times, cold mists and clouds heavy with moisture swept over the country, which during the winters was at times buried in snow, and subject to rapid changes of temperature. These climatic[3] conditions appear to be demonstrated by the predominance of the arctic tundra life, mammals which were adapted only to severe weather and attracted by the northern flora.

The summers were undoubtedly warm, like the present Arctic summers, but very much longer in these southerly latitudes. It is not improbable that there were seasonal migrations, northward and southward, of the mammoths, rhinoceroses, and reindeer, and also that the northern flint quarries along the Somme and the Marne may have been visited chiefly during the warm summer season. The Asiatic mammals had entirely disappeared from the regions of France and Germany during the first maximum of the fourth glaciation, but there are some who maintain that during the amelioration of climate that followed, an interval in the Alpine region termed the Laufenschwankung by Penck, the straight-tusked elephant and Merck’s rhinoceros again migrated into northern France. It is true that occasionally we find the bones of these animals in close association with those of the woolly mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. It is possible to explain such intermingling either as having occurred during the advance of the fourth glaciation, or as due to the northward and southward migration of the respective herds of mammals in the summer and winter seasons. As the period of the fourth glaciation continued it is certain that these Asiatic mammals entirely disappeared.

At the same time the Neanderthals had passed through the first stage of development of the Mousterian industry and had reached what is known as the Tull’ or ‘high’ Mousterian, which, [ p. 206 ] with few exceptions, was carried on under the shelter of the overhanging cliffs or within the grottos.

The mammalian life of these ‘full’ Mousterian times, as found along the headwaters of the Danube, the Rhine, and the branches of the Dordogne and V&ere, is divided among the various faunal groups as follows:

Life of Middle Mousterian Times

- Tundra Life.

- Woolly mammoth.

- Woolly rhinoceros.

- Scandinavan reindeer.

- Arctic fox.

- Arctic hare.

- Banded lemming.

- Arctic ptarmigan.

- Alpine Life.

- Alpine marmot.

- Ibex.

- Alpine ptarmigan.

- Steppe Life.

- Steppe horse.

- Steppe suslik.

- Moor-hen.

- Asiatic Life.

- Cave-lion.

- Cave-hyaena.

- Cave-leopard.

- Forest Life.

- Stag, lynx, wolf, fox, watervole, brown bear, giant deer.

- Cave-bear.

- Meadow Life.

- Bison.

- Wild cattle.

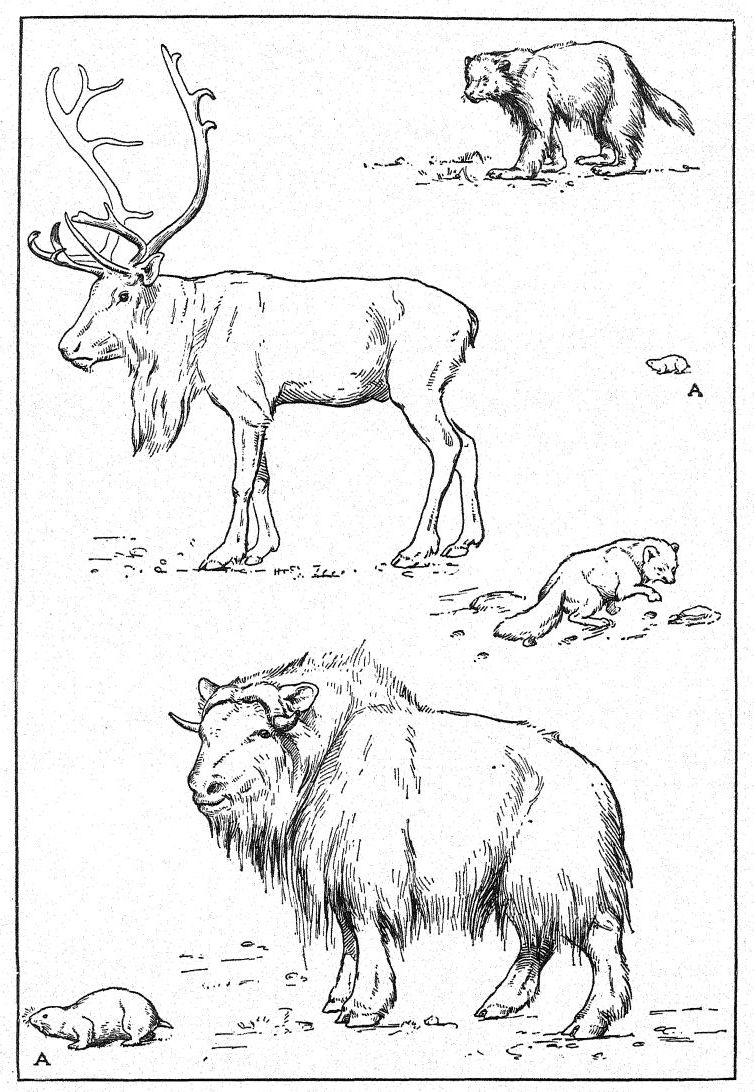

It would appear that the reindeer, the woolly mammoth, and the woolly rhinoceros were already widely distributed over western Europe, accompanied by the arctic fox (Cams lagopus), the arctic hare (Lepus variabilis), and the banded lemming (Myodes torquatus). There is no proof that the musk-ox had at this time reached its extreme southerly distribution, and it would appear that the arrival of the second type of northern lemming from the region of the river Obi (Myodes obensis) did not occur until the close of Mousterian times,21 because the great migration of these animals is recorded by their abundant remains in the so-called ‘lower rodent layer’ of all the stations along the Rhine and Danube, such as Sirgenstein, Wildscheuer, and Ofnet, after the final stage of Mousterian industry. In fact, this remarkable little rodent appears to mark the second maximum or close of the fourth glaciation by its migration all over western Europe, and wherever its remains are found in the grotto deposits they furnish one of the most important and positive of prehistoric dates, namely, that of the [ p. 207 ] ‘lower rodent layer.’ The lemmings surpass all other mammals in the great distances covered by their migrations, and it would appear that this northern species swept all over western Europe at the same time, leaving its remains not only in the caverns along the Danube but in those of Belgium and of Thiede, near Braunschweig. The latter station, Thiede, was not far from the southern border of the Scandinavian glacier ; it was subjected to a very severe arctic climate, as the only associates of the Obi lemming were the banded lemming, the arctic fox, the arctic hare, the reindeer, the mammoth, and the musk-ox.

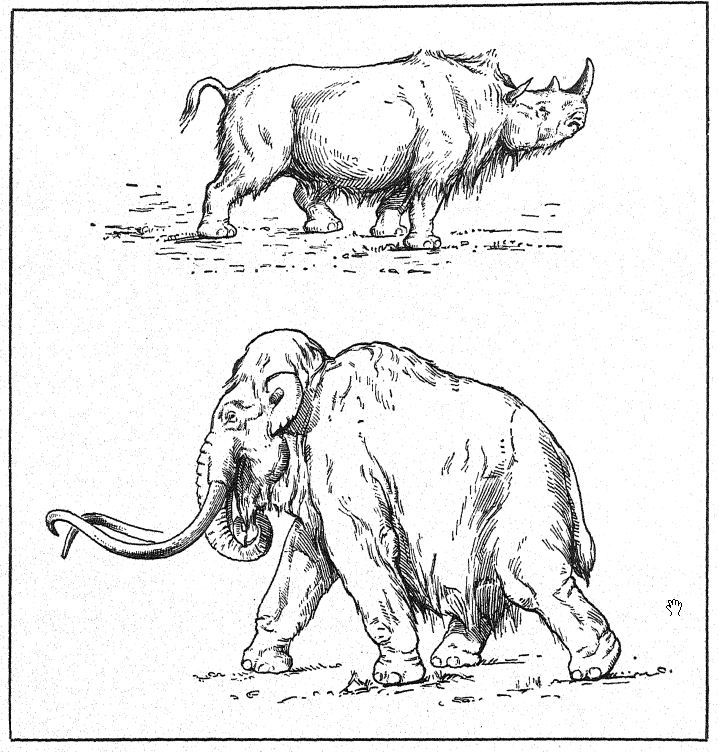

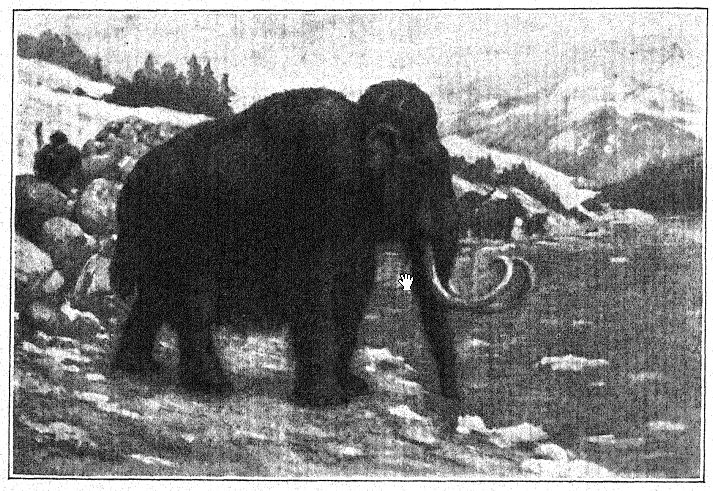

The woolly mammoth now reaches the height of its evolution and specialization ; as preserved in the frozen tundras of northern Siberia, and as represented in very numerous drawings and engravings by the Upper Palaeolithic artists, it is the most completely known of all fossil mammaha.22 Its proportions, as shown in the accompanying figure, which represents the information gathered from ah sources, are entirely different from those of either the Indian or African elephant. The head is very high and surmormted by a great mass of hair and wool; behind this a sharp depression separates the back of the head from the great hump on the back ; the hinder portion of the back falls away very rapidly and the tail is short ; the overcoat of long hair nearly reaches the ground, and beneath this is a warm undercoating of wool. It is not improbable that the humps on the head and the back were fat reservoirs. The color of the hair was a yellowish brown, varying from light brown to pure brown; woolly hair, from an inch to an inch and a half in length, covered the whole body; interspersed with the shorter hairs was a large number of longer and thicker hairs, which formed mane-like patches on the cheeks, chin, shoulders, flanks, and abdomen. A broad fringe of this [ p. 208 ] long hair extended along the sides of the body, as depicted in the work of the Upper Palaeolithic artists in the Combarelles Cave. Especially interesting to us is the food found in the stomach and mouth of the frozen Siberian mammoths, which consists chiefly of a meadow flora such as flourishes during the summer in northern Siberia at the present day, including grasses and sedges, wild thyme, beans of the wild oxytropis, also the arctic variety of the upright crowfoot (Ranunculus acer). This was the summer food. The winter food undoubtedly included the leaves and stems of the willow, the juniper, and other winter plants.

Life of Late Mousterian Times

Second Maximum of Fourth Glaciation

- Tundra, Steppe, Alpine, Asiatic and Meadow life, as above.

- Obi lemming.

- Musk-ox.

- Ermine.

- Arctic ptarmigan.

- Eversmann’s weasel (Steppe weasel).

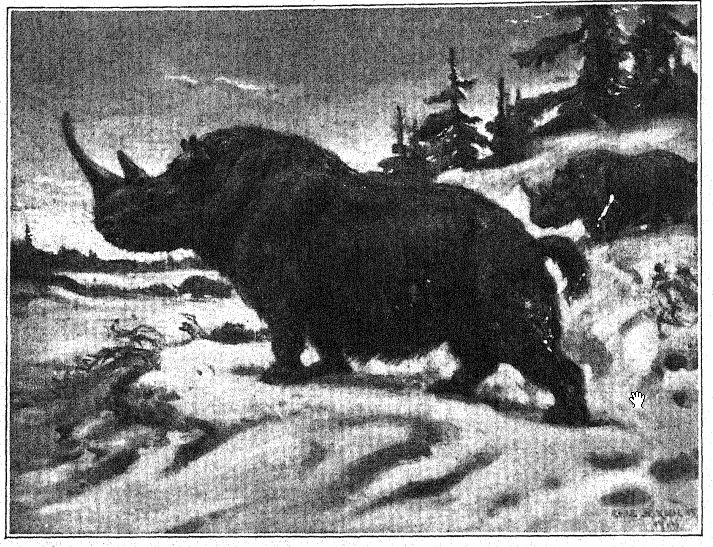

The woolly rhinoceros was the invariable companion of the mammoth, even as Merck’s rhinoceros always associated itself with the straight-tusked elephant. This remarkable animal is related to the northern African group of white rhinoceroses, from which it branched off at a very remote period. The profile of its very long, narrow head, of its enormous anterior and lesser posterior horn, and its humped back resembles that of the existing [ p. 209 ] African form, but its protection against the arctic climate gave it a wholly different outward appearance ; the hair of the face, of a golden-brown color, with an undercovering of wool, is preserved in the Museum of Petrograd. Through a discovery at Starunia, in eastern Galicia, in 1911, this animal is now completely known to us, except the tail ; its remains were found here at a depth of 30 feet, and included the head, left fore leg, and the skin of the left side of the body. The Starunia specimen has a broad, truncated upper lip adapted to grazing habits, small oblique eyes, long, narrow, and pointed ears, a long anterior horn with oval base, and a shorter posterior horn, a short neck, on the back of which is a small, fleshy hump, quite independent of the skeleton ; the legs are comparatively short. It differs from the living African form in the somewhat narrower muzzle, in its small, pointed ears, and in the presence of a thick coating of hair. Like the white rhinoceros, the woolly form was a plains dweller, living on grass and small herbs.23 This rhinoceros kept more closely to the borders of the great ice-sheets than did the mammoth, arresting its migration in Germany and France; that is, it did not migrate so far to the south as the mammoth, which wandered down into Italy as far as Rome.

The reindeer was the herald or forerunner of all the arctic tundra fauna ; it reached the valley of the Vézère at the beginning of the period of the true Mousterian culture and already had penetrated much farther south during the Third Glacial Stage, probably migrating along the borders of the ice-fields ; in fact, it is found in northern Europe even during the second glaciation. It is the true Scandinavian or barren-groimd species, which is now typified by two forms of the Old World reindeer (R. tarandus, R. spitzbergensis), and by the existing American barren-ground forms. The antlers are round, slender, and long in proportion to the relatively small size of the animal ; the brow tines are palmated. There is little proof that the Neanderthals made much use of the bones of the reindeer, but there is every reason to suppose that they used the pelts, for the preparation of which the Mousterian scrapers and planers were especially well fitted.

[ p. 210 ]

In the Iberian peninsula the tundra fauna did not penetrate as far south as Portugal, although the Norwegian lemming (Myodes lemmus) reached the vicinity of Lisbon. The woolly mammoth, accompanied by the woolly rhinoceros, has been discovered in two localities on the extreme northern coast of Spain, in the province of Santander, bordering the Bay of Biscay. The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) is ioxaid in the cavern of Seriha, south of the Pyrenees ; as early as Acheulean times it reached the region of Altamira, near Santander. Thus Harlé24 concludes it is certain that the tundra fauna spread from France westward into Catalonia, along the northern coast of Spain, flanking the Pyrenees. It is generally believed that the cave-bear (Ursus spelaus) occupied many of the caverns before their possession by man, and developed certain peculiarities of structure in these haunts. Thus the phalanges bearing the claws are feebly developed, [ p. 211 ] indicating that the claws had partly lost their prehensile function ; the anterior grinding-teeth are very much reduced, and the cusps of the posterior grinders are blunted in a way which is indicative of an omnivorous diet; yet the front paws were of tremendous size, the body was thick-set and of heavier proportions than that of the larger recent bears (Ursus arctos) of Europe. Hence, it would appear that the Neanderthals drove out from the caves a type of bear less formidable than the existing species but nevertheless a serious opponent to men armed with the small weapons of the Mousterian period.

¶ Customs of the Chase and of Cave Life

We have only indirect means of knowing the courage and activity of the Neanderthals in the chase, through the bones of animals hunted for food which are found intermingled with the flints aroimd their ancient hearths. These include in the early Mousterian hearths, as we have seen, bones of the bison, the wild cattle, and the horse, which are followed at Combe-Capelle by the first appearance of the bones of the reindeer. The bones of the bison and of the wild horse are both utilized in the bone anvils of the closing Mousterian culture at La Quina. What we believe to be the period of the great mammalian life of the region of the upper Danube is found in the Mousterian levels of the grotto of Sirgenstein, from which it would appear that the Neanderthals hunted the mammoth, the rhinoceros, the wild horse, bison, and cattle, and the giant deer as well as the reindeer. We should keep in mind, however, that when these caves were for a time deserted, the beasts of prey returned, and so it often happens that the succeeding layers afford proofs of alternate occupation by man and by beasts of prey of sufficient size to bring in the larger kinds of game, while owls may be responsible for the deposits of the lemming, as in the ‘lower rodent layer.’

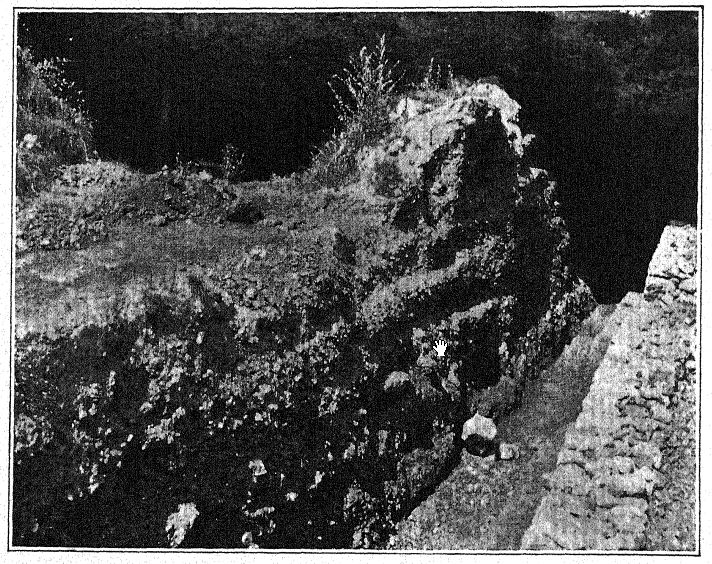

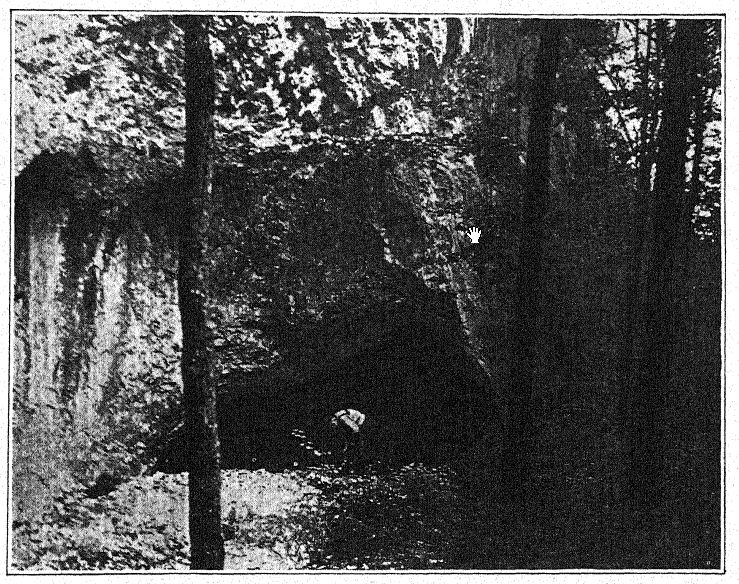

Obermaier25 has given careful study to the vicissitudes of cave life in Mousterian times. Long before these caves were inhabited by man, they served as lairs or refuges for the cave-bear [ p. 212 ] and cave-hyaena, as well as for many birds of prey. For example, the cave of Echenoz-la-Moline, on the upper waters of the Saone, contained the remains of over eight hundred skeletons of the cave-bear, and no doubt it cost the Neanderthals many a hardfought battle before the beasts were driven out and man possessed himself of the grotto. Fire may have been the means employed. It has been questioned whether the caves were not unhealthy dwelling-places, but it must be remembered that, except in certain caverns which had natural openings through the roof for the exit of smoke, there was no true cave life, but rather a grotto life, which centred around the entrance of the cave. The smallest cave, this author observes, was considerably larger and better ventilated than the small, smoky cabins of some of the European peasants, or the snow huts of the Eskimo. The most serious obstacle was the prevailing dampness, which varied periodically in the caverns, so that dry seasons were succeeded by abundant moisture seeping through the limestone roof and down the side walls. At such times the caverns were probably uninhabitable, and in the bones of both men and beasts many instances have been observed of diseased swellings and of inflammation of the vertebrae, such as are caused by extreme dampness. The compensating advantages were the shelter offered from the rain and cold, a constant temperature at moderate distances from the entrance, and also the fact that the caves were very easily defensible, because the entrance was generally small and the approach often steep and difficult; a high stone wall across the opening would have made the defense still easier, and a flaming firebrand would have prevented the approach of bears and other beasts of prey. On account of this shelter from the weather and wild beasts the grottos and the larger openings of the caverns were certainly crowded with the Mousterian flint workers during the inclement seasons of the year.

Yet the greater part of the life of the Neanderthals was undoubtedly passed in the open and in the chase. Throughout Mousterian times the commonest game consisted of the wild horse, wild ox, and reindeer. Both flesh and pelts were utilized, [ p. 213 ] and the marrow was sought by splitting all the larger bones. Thus, frequently we find in the hearths the remains of the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the giant deer, the cave-bear, and the brown bear. From these beasts of prey the Neanderthal hunters obtained pelts and perhaps also fat for torches used to light the caverns ; there is no proof of the invention of the lamp at this period.

The work of the women undoubtedly consisted of preparing the meals and making the pelts into covers and clothing. Whenever possible this would be done in the daylight outside of the grottos, but in chilly, rainy weather, or the bitter cold of winter, the whole tribe would seek refuge in the grotto, gathering around the fire-hearths fed with wood ; odd comers would serve as storehouses for fuel or dried meat, preserved against the days when extreme cold and blinding snow forbade the hunters to venture forth.

It appears that the game was dismembered where it fell and the best parts removed. The skull was split open for the brain; the long bones were preserved for the marrow; thus the bones of the flank and shoulder of game occur frequently in cave deposits, while the ribs and vertebrae are rare.

The pitfall may have been part of the hunting .craft known to the Neanderthals. The chase was pursued with spears or darts fitted with flint points, also by means of ‘throwing stones,’ which are found in great numbers in the upper Mousterian levels of La Quina, in the Wolf Cave of Yonne, Les Cottes, and various places in Spain. If one imagines, as is quite possible, that the throwing stone was placed in a leather sling or in the cleft end of a stick, or fastened to a long leather thong, one can readily see it would prove a very effective weapon.

The methods of chase by the Neanderthals are, nevertheless, somewhat of a mystery. There was a very decided disparity between the size and effectiveness of their weapons and the strength and resistance of the animals which they pursued. None of the very heavy implements of Acheulean times was preserved ; the dart and spear heads are not greatly improved, certainly [ p. 214 ] they could not penetrate the thick hides of the larger arctic tundra mammals, heavily protected with hair and wool; the chase even of the horses, wild cattle, and reindeer was apparently without the aid of the bow and arrow and prior to the invention of the barbed arrow or lance head.

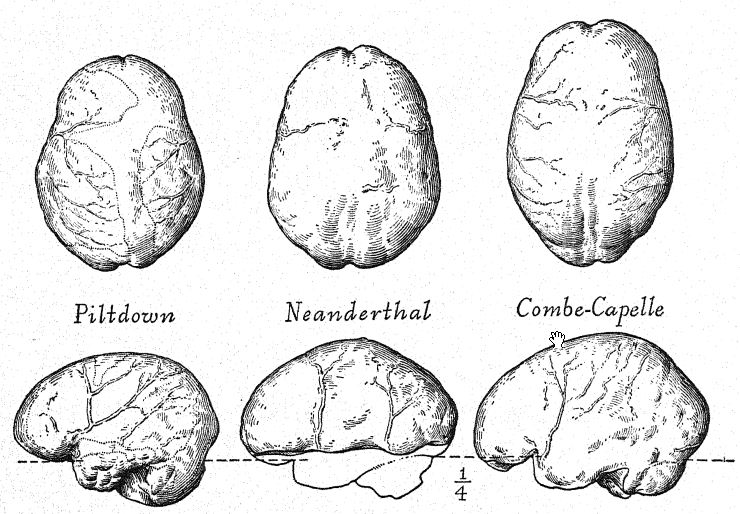

¶ Discovery of the Neanderthaloid Races

The open-air or nomadic life of all the tribes of western Europe from Pre-Chellean nearly to the close of Acheulean times was very unfavorable to the preservation of human remains. It is possible that the bodies of the dead and of the aged were thrown out to the hyaenas which surrounded the stations, as among some of the tribes of Africa to-day, but it is equally [ p. 215 ] possible that they were interred in sonae manner. Skeletons buried near the surface in the river sands or gravels of the ‘terraces’ would not have been preserved. We have seen that the preservation of the Heidelberg and Piltdowm remains was entirely due to chance, the bones having been washed doavn and mingled with those of the animals ; nor has any evidence been found in the grotto of Ehapina of ceremonial burial or of respect for the dead, but on the contrary there is some evidence of cannibalistic customs. Even before the close of early Mousterian times all this was changed. Perhaps the closer association enforced by the more rigorous climate indirectly produced greater respect for the dead and led to the custom of burial or the orderly laying out of the remains of the dead in the floors of the partly protected grottos and caverns, to which custom we owe our present knowledge of the structure of Neanderthal man in Mousterian times.

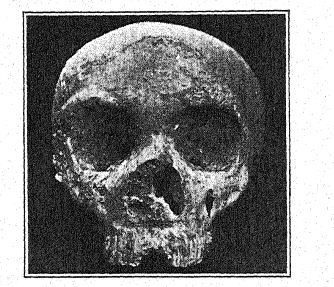

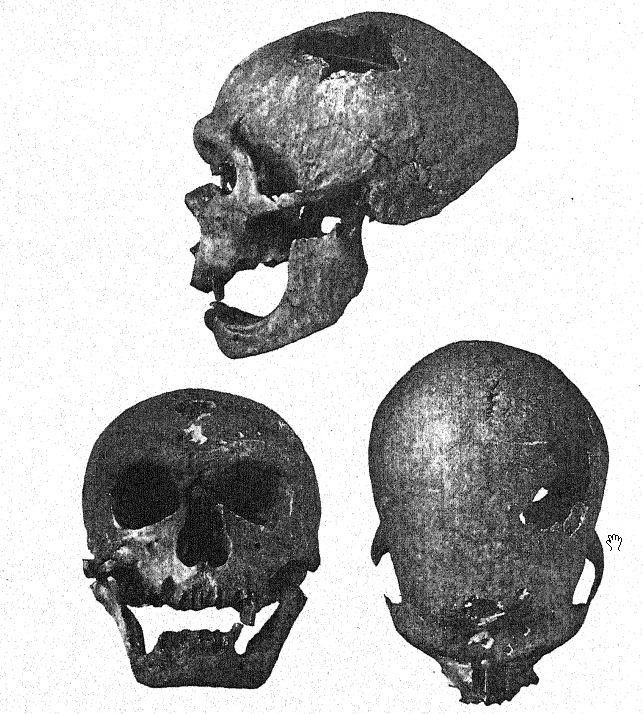

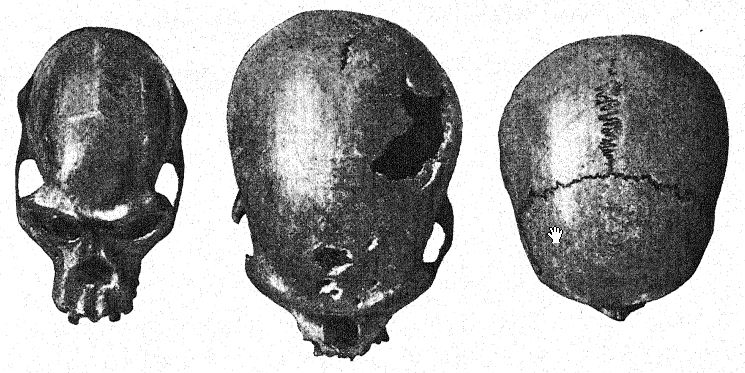

The first discovery of a Neanderthaloid was made in 184S, eight years before the type of the Neanderthal race came to light. This was the Gibraltar skull26 found by Lieutenant Flint, near Forbes Quarry, on the north face of the Rock of Gibraltar. It consists of a well-preserved skull, with the parietal bones only missing and the face and base of the cranium remarkably complete. In 1868 it was presented by Busk to the Museum of the [ p. 216 ] Royal College of Surgeons, in London, where it lies to-day. The exact site of the discovery can no longer be positively identified ; it was probably found in a still existing cave, and although its archasologic age cannot be determined, yet as its anatonaical features are those of the Neanderthal race, and as all the remains of this race which can be dated with certainty are of Mousterian age, it probably belongs to the Mousterian period. Of recent years its great importance in the history of man has been revealed in the studies of Sollas, Keith, and Schwalbe. Thus it has come to be ranked among the Neanderthaloids and is considered of a particularly primitive form, because of the extremely small size of the brain. This feature and the slight development of the supraorbital ridges, so characteristic of the Neanderthaloids, are explained by the theory that the skull belonged to a female.

Sera27 considers the Gibraltar skull to be the most ape-like of all human fossils and thinks it should not be classed with the Neanderthaloids at all, but should be regarded as Pre-Neanderthaloid; this view is shared by Keith. Boule, however, believes that this skull is of the same geologic age as that of Spy, La Chapelle, La Ferrassie, and La Quina ; everything leads us to believe,28 he remarks, that the skull of Gibraltar is a female skull of Neanderthal type. He elsewhere refers to the skulls of Gibraltar, [ p. 217 ] of La Quina, and of La Ferrassie II as probably those of female Neanderthals.

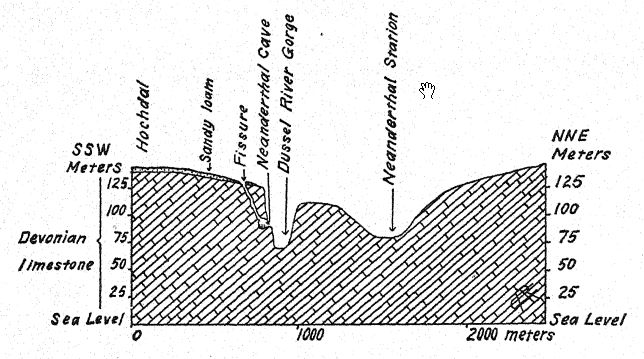

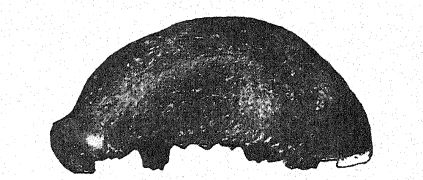

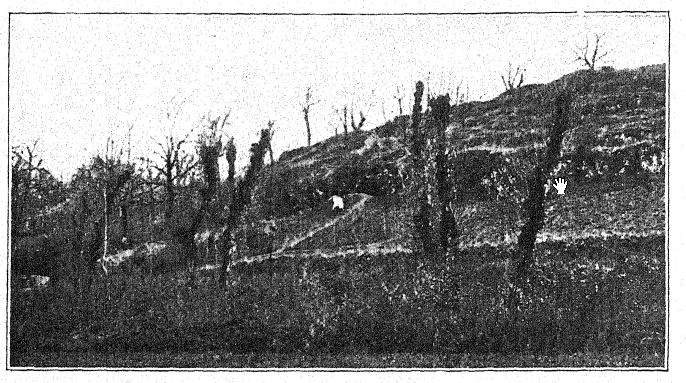

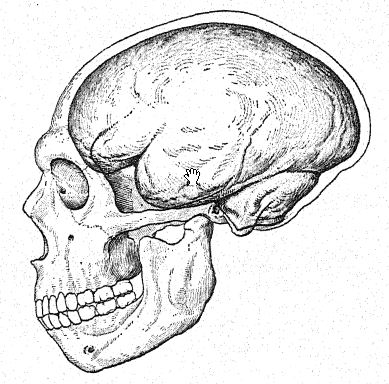

The type skull of this great extinct race of men is that of Neanderthal—certainly the most famous and the most disputed of all anthropologic remains—appreciated by Lyell and Huxley, but passed over by Darwin, and finally established by Schwalbe as the most important missing link between the existing species of man (Homo sapiens) and the anthropoid apes. In 185629 some workmen were engaged in clearing a small loam-covered cave about six feet in height, the so-called Feldhofner Grotto, in the cretaceous limestone of the valley known as the Neanderthal, on the small stream Düssel flowing between Elberfeld and Düsseldorf. They discovered some human bones, probably a complete skeleton representing an interment, which, unfortunately, were allowed to be scattered and crushed. Doctor Fuhlrott rescued the parts that remained, including the now famous skullcap, both thigh-bones, the right upper-arm bone, portions of the lower arm, bones of both sides, the right collar-bone, and fragments of the pelvis, shoulder-blade, and ribs. All the bones were perfectly preserved and are now to be found in the provincial museum of Bonn.

The discovery made a great sensation, but at first the age of these fossils remained doubtful ; some 150 paces from the grotto, in a similar small cave were found bones of the cave-bear and rhinoceros. In 1858 Schaaffhausen’s memoir30 appeared, in which he gave the first detailed description of these remains as belonging to a primitive original race differing in every point from recent man, and he never wavered from this standpoint. [ p. 218 ] In 186331 Busk, Huxley, and Lyell also placed this skeleton in its true intermediate position between man and the anthropoid apes. The determined opinion of Virchow that this was not a normal type of man exerted so great an influence that not until the classic work of Schwalbe,32 between 1899 and 1901, did this skeleton assume its commanding importance for all time, and even this was subsequent to the discovery of two other Neanderthaloid races.

At first, quite erroneously, this was associated with the socalled race of Cannstatt, but long before Schwalbe’s work it was recognized by King,33 in 1864, as a distinct species of man (Homo neanderthalensis) ‘the man of the Neander valley.’ Not long after the discovery of the Meander thaloids of Spy, in Belgium, Cope,34 in 1893, proposed the same specific name of Homo neanderthalensis. In 1897 Wilser35 suggested the name of Homo primigenius, which has been widely adopted in Germany, while among French authors the same species of man is sometimes known to-day as Homo mousieriensis. This variety of names serves at least to record the unanimous opinion that this mid-Pleistocene man belongs to a distinct species.

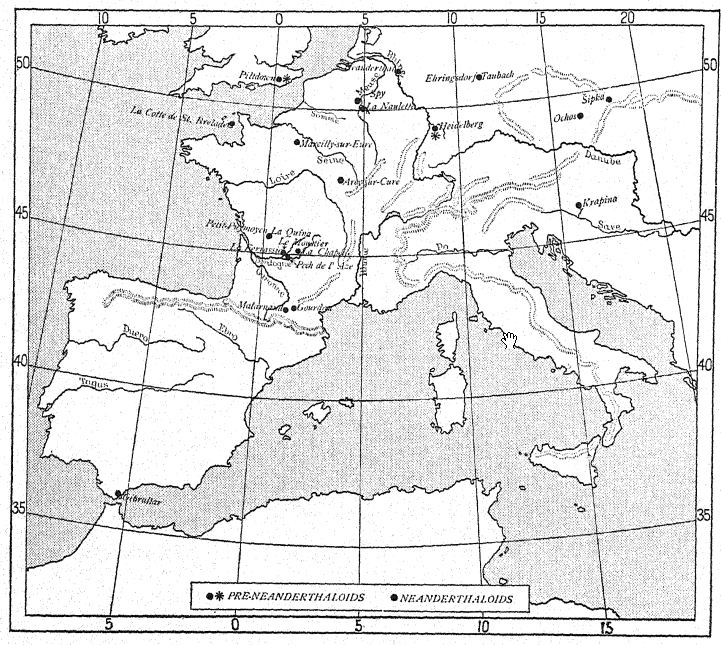

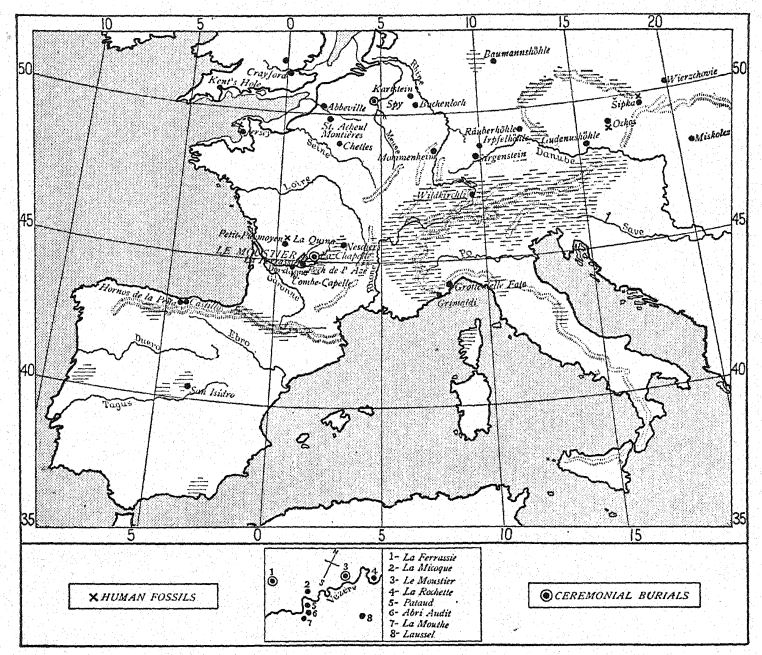

Since the race was very widely distributed, we may speak of these people as the ‘Neanderthals,’ while races resembling the Neanderthal species may be characterized as ‘Neanderthaloid.’ The complete series of discoveries of members of this race is now very large indeed.

In the year 1887 the Belgian geologists Fraipont and Lohesy36 discovered in a grotto near Spy, not far from Dinant on the Meuse, the remains of two individuals which are now distinguished as Spy I and Spy II. In the same stratum with the skeletons, beneath a layer of tufaceous limestone, flint implements of Mousterian age were embedded, together with remains of the woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, cave-bear, and cave-hyaena. This discovery is one of the most important in the history of anthropology, because it definitely dated the Spy men as belonging to the period of Mousterian industry, and also because the authors immediately recognized these men as belonging to the race of [ p. 219 ] [ p. 220 ] Neanderthal and of Cannstatt, which at the time were supposed to be the same. Here for the first time the proportions of the cranium and the brain, the very primitive features of the lower jaw and of the teeth, the low stature, and several ape-like characters of the limb bones became known ; here were observed the prominent supraorbital ridges of the Neanderthal type, the receding forehead, the cranial profile inferior to that of the lowest existing Australian races, the narrow, dolichocephalic skull.

DISTRIBUTION OF THE REMAINS OF THE NEANDERTHALS (Compare Fig. 104)

| I. Of Unknown Lower Palaeolithic Times | |||

| 1848. | Gibraltar. | Forbes Quarry. | Fragmentary skull. |

| 1856. | Neanderthal. | Düsseldorf, Germany. | Skullcap and skeletal fragments. |

| 1859. | Arcy-sur-Cure. | Yonne, France. | I lower jaw. |

| 1866. | La Naulette. | Belgium. | I lower jaw. |

| 1888. | Malarnaud. | Ariege, France. | I lower jaw. |

| ?Gourdan. | Hautes-Pyrenees . | I lower jaw. | |

| 1906. | Ochos. | Moravia. | I lower jaw. |

| 2. With Late Mousterian Industry | |||

| 1887. | Spy 1 , 11. | Near Dinant, Belgium. | Two skulls and skeletons. |

| 1907. | Petit-Puymoyen. | Char elite, France. | Fragments of upper and lower jaws. |

| 1909. | Pech de l’Azé. | Dordogne, France. | Skull of a child. |

| 1910. | La Ferrassie II. | Dordogne, France. | I skeleton (female). |

| 1911. | La Cotte de St. Brelade. | Isle of Jersey. | 13 human teeth. |

| 1911. | La Quina II. | Charente, France. | Skull and fragments of skeleton. |

| 3. With Middle Mousterian Industry | |||

| 1982. | Sipka. | Moravia. | Jaw of a child. |

| 1908. | La Chapelle-aux-Saints. | Correze, France. | Almost complete skull and skeleton. |

| 1909. | La Ferrassie I. | Dordogne, France. | Portions of one skeleton. |

| 1910. | La Quina I. | Charente, France. | Foot bones. |

| 4. With Early Mousterian Industry | |||

| 1908. | Le Moustier. | Vézère Valley, Dor dogne, France. | Skeleton of a youth. |

| 1914. | Ehringsdorf. 37 | Near Weimar. | Lower jaw. |

| 5. With Mousterian or Acheulean Industry | |||

| 1899. | Krapina. | Croatia, Austria-Hungary. | Portions of many skeletons of adults and of children. |

| 1892. | Taubach. | Near Weimar. | I milk tooth. |

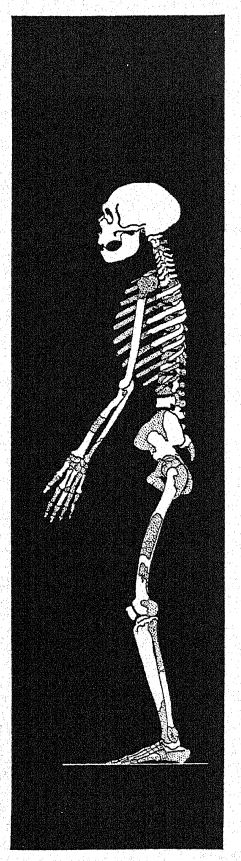

The limbs were found to have retained the anthropoid disproportion between the thigh-bone and the shin-bone, and the important discovery was made that this short, massively built, heavy-browed, dull-visaged Neanderthal man was unable to stand absolutely erect, the structure of the knee-joint being such that the knees were constantly slightly bent. In other words, the Spy man had not yet fully acquired the erect position of the lower limbs.

This discovery may be said to have established the Neanderthals in all their characters as a very distinct low race, but twentytwo years elapsed before this was further confirmed by the finding of another and still earlier type of Neanderthaloid at Krapina, in northern Croatia, Austria-Hungary, as described at the close of Chapter II (p. 181 above) ; at type which with its local variations [ p. 221 ] was soon determined as unquestionably belonging in tbe same group with the man of Neanderthal and the men of Spy.

Many years before, namely, in 1866, the Belgian anthropologist Dupont38 had discovered the remains of another member of this race in a grotto on the bank of the River Lesse, near La Naulette, not far from Furfooz, in northern Belgium. This is now known as the La Naulette jaw and is found to be of Neanderthal type. It was associated with bones of the woolly mammoth, the rhinoceros, the reindeer, and a few fragments of other human bones.

Again, in 1882, Maska39 found in a cave near Sipka, in Moravia, south of Sternberg, and six miles east of Neutitschein; fragments of a child’s lower jaw, extraordinarily strong, thick, and large, and showing the incoming of the permanent teeth. From this very same region is the jaw of Ochos, Moravia, found by Rzehak40 about 1906. Only the alveolar part of the jaw was found, but it served to demonstrate the very wide geographical distribution of the Neanderthal race.

At this time the Dordogne region, long known to be an intensive centre of Mousterian industry, from the time of Lartet’s discovery of Le Moustier, in 1863, had not yielded a single skeleton, or any anatomical evidence of the type of man which in Mousterian times inhabited it. But beginning in the spring of 1908 there came in succession a whole series of such discoveries, mostly of ceremonial burials, at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, at the type station of Le Moustier itself, at La Ferrassie, another station on the lower Vézère, and at La Quina.

In October, 1910, was discovered the skull known as La Ferrassie II, of late Mousterian age; it is probably that of a female, and the remains were arranged in what was presumably a special form of ceremonial burial, because the bones, instead of being laid out straight in a certain direction, were in a crouching or flexed position (see Appendix, Note X).

The Le Moustier skeleton was found by Hauser in the lower grotto of Le Moustier, in the Vézère valley, in the spring of 1908, and carefully removed with the aid of Professor Klaatsch.41 [ p. 222 ] It belonged to a youth some sixteen years of age. The most interesting feature of the discovery was the manner in which the skeleton was laid out.42 The head rested on a number of flint fragments carefully piled together—a sort of stone pillow; the dead lay in a sleeping posture, with the head resting on the right forearm. An exceptionally fine coup de poing was close by the hand, and numerous charred and split bones of wild cattle (Bos primigenius) weie placed aroimd, indicative of a food offering. The flints were believed to belong to the Acheulean stage, which underlies the layer of true Mousterian industry, long known in this locality; but by French archaeologists and by Schmidt these implements are regarded as of the earliest Mousterian age, in which it is well known that the Acheulean coup de poing still persisted. Unfortunately, the skeleton was not very well preserved and, while Edaatsch was entirely justified in classifying it with the Neanderthaloids, it should be regarded not as a distinct species (Homo mousteriensis hauseri) but rather as a member of the true Neanderthal race (Homo newnderthalensis). It also proves to be a rather stocky individual, robust and of low stature: the arms and legs are relatively short, especially the forearm and the shin-bone.

[ p. 223 ]

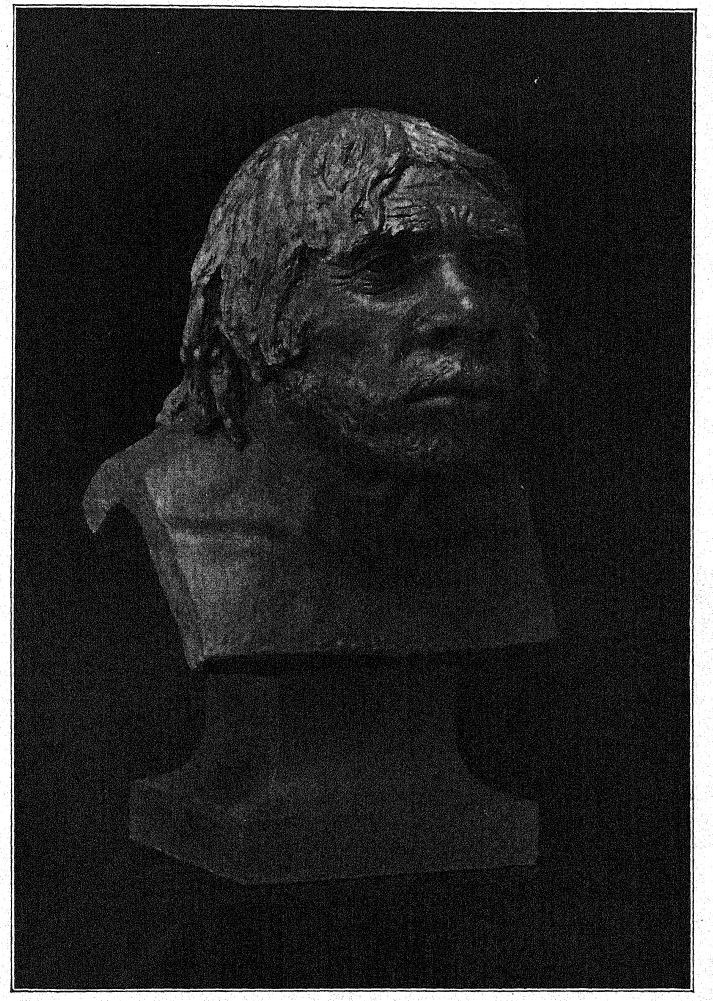

At the same time that the skeleton of Le Moustier was being disinterred, the Abbés A. and J. Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon43 were exploring the Mousterian culture of the grotto near La Chapelle-aux-Saints, a few miles to the eastward of Le Moustier, and came upon a skeleton which has proved to be by far the finest of all the Neanderthaloid fossils, including a remarkably well-preserved skull, almost the entire back-bone, twenty ribs, bones of the arm and of the greater part of the leg, and a number of the bones of the hands and feet. This was also a ceremonial burial of an individual between fifty and fifty-five years of age, most carefully laid out in an east-and-west direction in a small, natural depression. With it were found typical Mousterian flints, also a number of shells and remains chiefly of the woolly rhinoceros, the horse, the reindeer, and the bison. The finding of a mature skull with the bones of the face in position, and in a relatively perfect state of preservation without distortion of the entire cranium, afforded for the first time the [ p. 224 ] opportunity of finally determining not only all the skeletal characters and proportions of Neanderthal man but also the actual size and proportions of the brain. This superb specimen was sent to the Paris Museum, and Boule’s preliminary descriptions44 and finally his almost faultless monograph45 aroused world-wide interest in the Neanderthal race.

A year later a third Neanderthal skeleton was discovered in the cave of La Ferrassie not far from Le Bugue, Dordogne, by Peyrony. The bones were badly shattered, and the proofs of ceremonial burial were not perfectly clear, but at a glance the skeleton was clearly recognized from the characters of the skull. [ p. 225 ] and particularly from those of the forehead, as belonging to the Neanderthal race.

In the succeeding year, 1910, in the cavern of La Quina, Department of Charente, to the north of the Vézère region46 were found the foot bones of a man precisely resembling the La Chapelle type, and again in 1911 several parts of the skeleton of another entirely typical member of the Neanderthal race were discovered in the earliest Mousterian strata. The skull bones were somewhat separated at the sutures. This was certainly not a case of ceremonial burial. Like the Gibraltar skull, this is supposed to be that of a female.

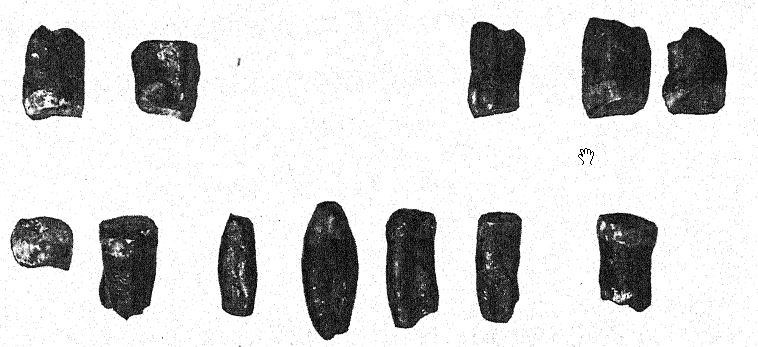

Of especial geographic interest is the discovery by Nicolle and Sineh47 of thirteen human teeth in a Mousterian cavern on St. Brelade’s Bay, on the Island of Jersey,48 which furnishes proof of the extension of the Neanderthal race to the Channel Islands, when these were, in all probability, still a part of the mainland. The teeth were associated with bones of the woolly rhinoceros, of the reindeer, and of two varieties of the horse, as well as with evidences of Mousterian hearths and flint implements. The distinctive features of the Neanderthal grindingteeth are the stout size, deep implantation, and expanded form of the roots, which, with the heavy jaw, point to the toughness of the food and to the muscular strength exerted in mastication. [ p. 226 ] The roots, instead of tapering to a point below, as in modern man, form a broad, stout column, supporting the crown, adapted to a sweeping motion of the jaw. This special feature alone would, exclude the Neanderthals from the ancestry of the higher races.

Thus, through a long series of discoveries, beginning in 1848 and rapidly multiplying during the last few years, we have found the materials for a complete knowledge of the skeletal structure of the men, women, and children of the Neanderthal race ; we know the relative brain development as well as the stature of the sexes; we have determined that this race, and this only, extended over all western Europe during late Acheulean and the entire period of Mbusterian times, and we have also learned that it was a race imbued with reverence for the dead and therefore probably animated by the belief in some form of future existence.

¶ Characters of the Neanderthal Race

The skulls and skeletons49 of Neanderthal, Spy, Krapina, Le Moustier, La Chapelle, La Ferrassie, and Gibraltar have so many distinctive features in common that it is beyond question that they must be classed in a closely related group. The distinctive features of this group are :

First, features found also in the different existing races of man, but never in the anthropoid apes, and therefore human ; second, features, all of which have never been found combined in any race of recent man, the group, therefore, represents a distinct species of man; third, features outside of the limits of variation in the recent races of man, and intermediate between them and the variation limits of the anthropoid apes.

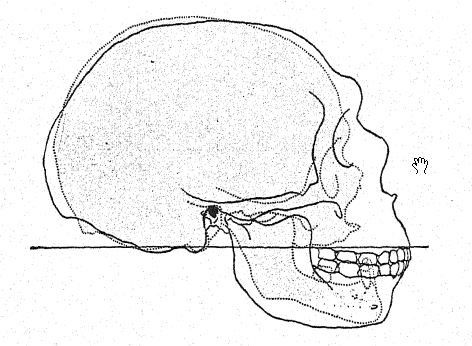

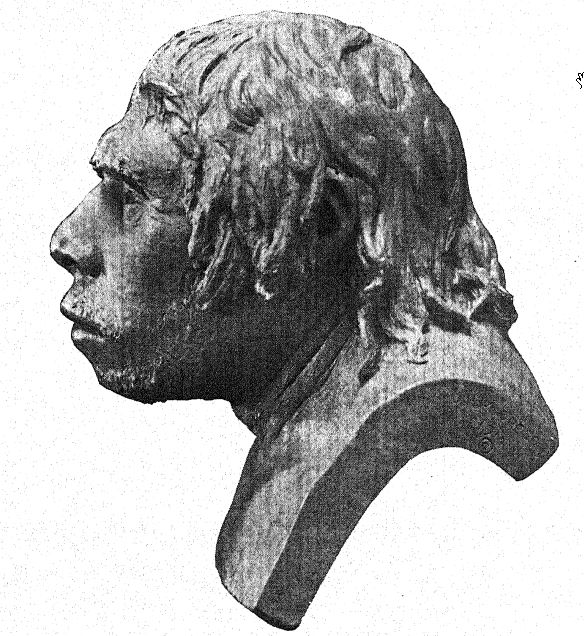

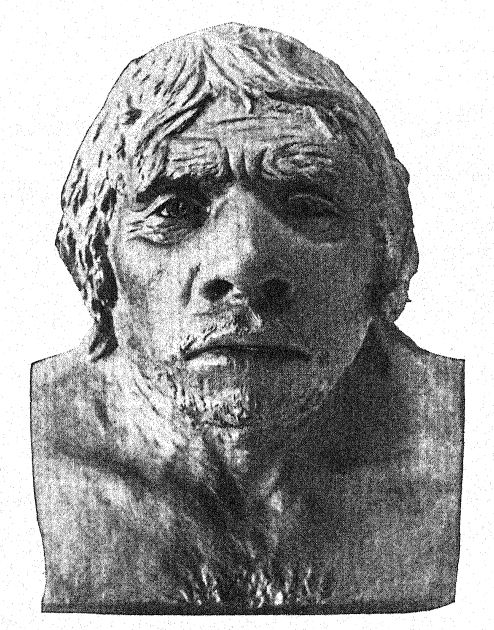

Before looking at Neanderthal man as a whole, we may turn our attention especially to a number of these peculiar features of the race. All the earliest observers were impressed by the heavy, overhanging brows and retreating forehead. In recent man there is often a decided prominence above the eyes, from the glabella or median point above the nose outward toward each side, but generally the outer third of the margin of these prominences [ p. 227 ] turns upward beneath the outer line of the eyebrows. In the Neanderthals, on the contrary, these prominences beneath the eyebrows surround the whole upper edge of the eye socket, extending outward around the external borders of the forehead, so that they may be called ‘tori supraorbitales’ ; the extent of this prominent ridge above and to the sides forms a veritable roof over the eye sockets, which appear like two deep, lateral caverns. Such lateral prominences do occur, though rarely, in recent man; they are observed, for example, in certain Australians.

The front view of the Neanderthal face, as seen in the female Gibraltar skull, in which these eyebrow ridges are by no means so prominent as in the male skulls, is no less remarkable for the great height of the face as compared with the flatness of the forehead. Placing the skull side by side with that of the Australian,50 we observe at once the enormous difference in the proportions of the face and the cranium in these two types, although the Austrahan represents one of the lowest existing races of Homo sapiens; we observe in the Gibraltar skull the very wide space between the eyes and the very large size of the narial opening, which indicate a broad, flattened nose; there is a correspondingly long space between the bottom of the narial opening and the line for the insertion of the incisor teeth, indicating a very long upper lip.

[ p. 228 ]

The jaw is less powerful than that of the Heidelberg man. The Heidelberg jaw we have seen to be distinguished by its general strength and clumsiness and its lack of chin, or rather a chin without the slightest indication of a prominence; on the inside of this very thick, rounded chin plate, the characteristic chin spine (spina mentalis) is lacking; instead, a double groove is present as the point of attachment for the muscles which connect the chin and tongue with the hyoid bone; the ascending process for the attachment of the muscles of the jaw is seen to be unusually broad, 60 mm., in contrast to about 37 mm. in the recent jaw ; finally, the condyle for attachment with the skull is particularly large.51

Like the Heidelberg jaw, that of the Neanderthals is distinguished by great thickness and massiveness. In general the contours are similar ; in a few instances the chin process is suggested by a slight prominence, but in general the chin is strongly receding, and it agrees with that of Heidelberg in lacking the spina mentalis. In other characteristics there are decided differences in the Heidelberg and Neanderthal jaws. The form of the latter is now known from the specimens of Krapina, of Spy, of La Naulette, of Ochos, and of Sipka, and from the perfect examples of Le Moustier and La Chapelle. The Sipka specimen [ p. 229 ] proves that even in a child ten years of age the jaw was remarkable for thickness and strength. Boule52 entirely agrees with Gorjanovic-Kramberger53 that the chin in the Neanderthal jaw was only in process of formation, and throughout life attained no more than an infantile form, that the Neanderthals may be ranked, however, as Homines mentales, whereas the Heidelbergs, in which the chin is entirely lacking, may be regarded as Homines amentales.

The proportions of the teeth in the Neanderthals are equally distinctive, especially in the size of the true grinders and cutting teeth. As in the Heidelberg jaw, they form a closely set row, from which the canine does not project as in the Piltdown dentition; in fact, the contour of the jaw and the proportions of the teeth are distinctly human when compared with the oranglike jaw of the Piltdown man. The grinding surface of the teeth has many layers of enamel, and the cusps are well developed. Unlike those of recent man, the incisors display folds of enamel on the inner or lingual surfaces, a condition rarely observed in the modern cutting teeth. In the teeth of the Heidelberg jaw, the pulp cavities are exceptionally large, whereas in the teeth of the Krapina race there is the urnque featmre that the molars have no normal roots, the roots having been more or less absorbed, a very rare occurrence in recent man. The dentition of La Chapelle is also distinctly human, but extraordinarily massive, corresponding with the general massiveness of the skull and masticating apparatus ; in detail it is not that of civilized races, but an exaggerated form of the type called macrodont.54 The elongation of the crown is also similar to what is termed hypsodont.

The grinding-teeth do not all show this massive size and columnar form, for about fifty per cent of the Krapina teeth have distinct roots and are more like normal modern grinders. In the Neanderthaloids of Spy the teeth are small and the roots are of moderate size.55

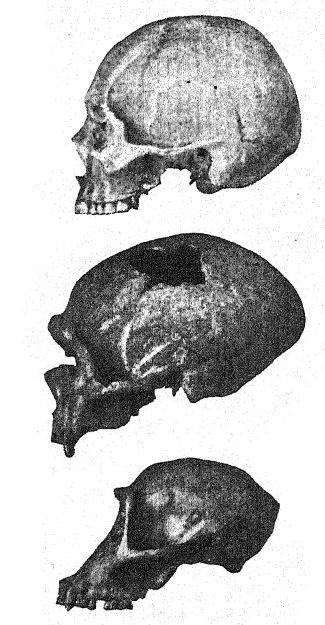

This study of the forehead and of the eyebrow ridges, of the great depth of the face, and of the peculiarly high, square form of the eye sockets prepares us for a profile view of the skull of [ p. 230 ] La Chapelle in contrast with that of the most highly developed and intellectual European type, namely, the profile of the distinguished American palseontologist, the late Professor Edward D. Cope, who bequeathed his skull and skeleton for purposes of scientific study and comparison. In La Chapelle we at once notice the platycephaly, or flattening of the skullcap, the retreating forehead, the great prominence of the eyebrow ridges resembling that of the anthropoid apes, the lengthening of the face as compared with the flattening of the cranium, the great prominence or prognathism of the face as a whole, and the special prominence of the rows of cutting teeth as compared with the vertical or indrawn line, and the recession of the tooth row in the Cope profile. This comparison also brings out the striking contrast between the high chin prominence of Homo sapiens and the deeply receding chin of the Neanderthals. The contrast is hardly less remarkable in the superior view of the skull in which the Neanderthal type is seen to be extremely dolichocephalic, the back of the skull being relatively broad and the front narrowing in the region of the forebrain until it suddenly expands in the prominent supraorbital processes.

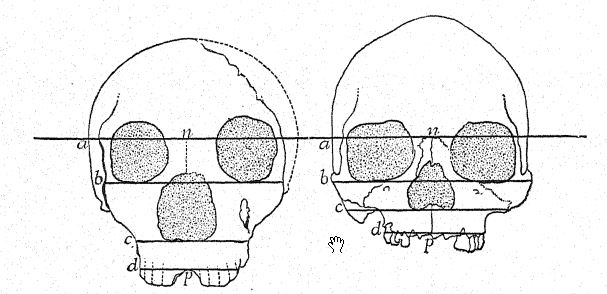

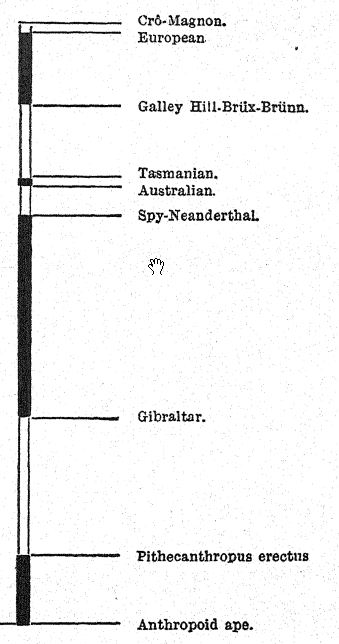

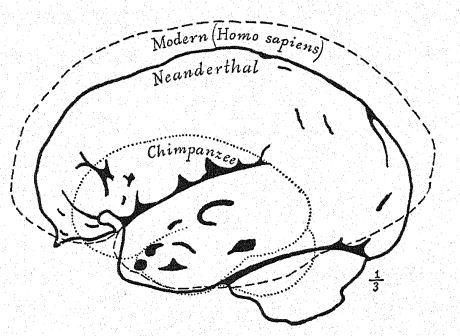

As shown in the diagram on page 8, Fig. i, the greatest [ p. 231 ] length of the Neanderthal skull is found on the horizontal line directly through the brain chamber, known as the glabella-inion line, a line drawn from a prominence between the eyebrow ridges to a point at the back of the skull known as the external occipital protuberance, or inion. This is also the longest hne in the skulls of Spy and of La Chapelle, as well as of the anthropoid apes,56 but in the north Australian skull. Fig. 1, owing to the greater expansion of the upper part of the brain, the greatest length of the skull is at a point considerably above the glabella-inion line. The median section of the skull of the chimpanzee, of the Neanderthal, and of the north Australian displays in a very striking manner the generalization made by Schwalbe, in 1901, that the Neanderthal skull is truly an intermediate or half-way form between that of the anthropoid apes and that of Homo sapiens. We observe in this illuminating section the growth of the dome of the skull, that is, the great brain-bearing cavity above the glabella-inion line g-i, by noting the contrast in the length of the vertical line of the cranial height, as compared with the space below the glabella-inion line indicated by the letters. This very important vertical line terminates below at the opening, where the spinal cord enters the base of the brain (see Fig. 1).

[ p. 232 ]

In many characteristics the Neanderthal skull is shown to be nearer to that of the anthropoid apes than to that of Homo sapiens. This conclusion arrived at by Schwalbe, in 1901,57 has been more than confirmed by Boule’s masterly study58 of the very complete skull of La Chapelle. After his detailed review, he concludes : As to the unity of the Neanderthal head form, these features are not peculiar to the skull of La Chapelle; in every case they are also found in the skulls of Neanderthal, Gibraltar, Spy, Krapina, La Ferrassie, which witness to the homogeneity of that human fossil type called Neanderthal. These features show a structural affinity between the fossil men of the Mousterian period and the anthropoid apes. It must be noted that many of these features may be found also in recent human skulls of the inferior races, but that they are very rare, very scattered, very isolated, and occur only as aberrations. It is the accumulation of all these features in every skull of a whole series which constitutes an assemblage entirely new and of great importance. In the skull, as in other parts of the anatomy of the Neanderthals, we should not expect to find every character intermediate between the anthropoids and recent man. The long Neanderthal face is somewhat similar to that of the Eskimo and is in contrast with the very short face of the existing Australians and Tasmanians. The depression at the root of the nose, just below the glabella, is very marked in all Neanderthals; there is less of the nose bridge than in any recent races, except those of the male Australians, yet the nose is not flattened but somewhat arched or aquiline. This feature is not characteristic of all the anthropoid apes, and in this respect the Neanderthals, Australians, and Tasmanians are more different from the anthropoid apes than are some of the white races; thus the Neanderthal nose, far from resembhng that of the anthropoids, differs from it more than does that of some recent human types.59 Many anatomists, following Huxley, have described the Australian and Tasmanian skulls as more or less Neanderthaloid, and some authors have gone so far as to regard these races as surviving Neanderthals. It is true that some of the skulls in these existing races are extraordinarily [ p. 233 ] platycephalic and show a retreating forehead, that others show supraorbital ridges almost as prominent as in the Neanderthals, that sometimes the prominence of the occipital inion is very marked, that certain jaws show a very retreating chin. Thus one or another of these Neanderthal features has been observed in these lower existing races, but all of these characteristics have never been combined in one race as constant features, and invariably associated, as in all the skulls of the Neanderthals known to us.

In brief, the Australian type of head has nothing in common with that of the Neanderthals except in a small number of characteristics in the region of the forehead and of the nose. The distinguishing traits of the Neanderthal head and face are platycephaly, a retreating forehead, flattening of the occiput or lower portion of the skull, prominence of the supraorbital ridges, chin retreating or lacking, projection of the entire face owing to the peculiar form of the upper jaw, and the relatively small size of the trontal lobes of the brain. In fact, concludes Boule : “All these modern so-called ‘Neanderthaloids’ are nothing but varieties of individuals of Homo sapiens, remarkable for the accidental exaggeration of certain [ p. 234 ] anatomical traits which are normally developed in all specimens of Homo neanderthalensis. The simplest explanation of these accidents in most cases is atavism or reversion. We cannot assert that there has never been an infusion of Neanderthaloid blood in the groups belonging to species Homo sapiens, but what seems to be quite certain is that any such infusion can have been only accidental, for there is no recent type which can be considered even as a modified direct descendant of the Neanderthals.”

This opinion is confirmed by the latest and most exhaustive researches of Berry and Robertson,60 who conclude that neither Australians nor Tasmanians have any direct relationship with Homo neanderthalensis ; the superficial points of cranial resemblance are explicable solely on the grounds of the remoteness of the ancestry. The Australians and Tasmanians are descendants not of the Neanderthal stock but of a late Pliocene or early Pleistocene stock, which, following Sergi, may be called Homo sapiens tasmanianus, of which the Tasmanian aboriginal, now extinct, was the almost unchanged offspring. In respect to ‘low’ characters, as shown in the diagram. Fig. 117, the Spy-Neanderthal skulls stand quite close to the Tasmanians and Australians, and the Gibraltar skull stands midway between this type and Pithecanthropus with respect to twelve different characters of comparison.

It is interesting to note[4] that the Tasmanians were found in a stage of flint industry very similar to that practised by the Neanderthals in Mousterian times ; their flints were made from artificially produced flakes, including a few examples61 that exhibited a neatness of edge trimming and resultant regularity of outline, whereas the greater part were characterized by an unskilful trimming and irregular outline ; the low status of the Tasmanian implements can most correctly be described by the word Pre-Aurignacian, that is, of Mousterian or of an earlier stage, but not by any means ‘Eolithic.’

[ p. 235 ]

The brain of Neanderthal man was known to be of large size even when estimated from the thal type. Darwin was compelled to admit that the famous skull of Neanderthal was well developed and capacious, and Broca offered an ingenious explanation of the otherwise inexplicable fact that the mean capacity of the skull of the ancient cavedweller is greater than that of many modern Frenchmen, namely, that the average capacity of the skull in civilized nations must be lowered by the preservation of a considerable number of individuals, weak in mind and body, who would have been promptly eliminated in the savage state, whereas among savages the average includes only the more capable individuals who have been able to survive under extremely hard conditions of life. The skulls of La Chapelle and of Spy afforded an opportunity of determining this very interesting problem, and the results entirely confirm the earlier estimates of Schaaffhausen and of Broca as to the great cubic capacity of the Neanderthal brain. The estimates in descending order are as follows:

[ p. 236 ]

| Skull of Spy II (Fraipont) | ? 1723 c. cm. |

| “ La Chapelle (Boule, Verneau, and Rivet) | 1626 “ |

| “ Spy I (Fraipont) | 1562 “ |

| “ Neanderthal | 1408 “ |

| “ La Quina, female (Boule approximation) | 1367 “ |

| “ Gibraltar, female (Boule estimate) | 1296 “ |

The size of the brain in the existing races of Homo sapiens varies from 950 c. cm. to 2020 ccm.63 Thus in respect to the volume of cerebral matter the brain of the Neanderthal man is surely human, but in form the brain lacks the proportions characteristic of the superior organization of the brain in recent man. In another important respect it is human: in the larger size of the left hemisphere, indicating the development of the use of the right hand. In its general form the brain is more like that of the anthropoid apes in the relatively smaller size of the frontal portion, in the simplicity and length of the convolutions, and in [ p. 237 ] the position and direction of the great fissures at the side known as the ‘fissures of Sylvius’ and of ‘Rolando.’ As studied by Boule and Anthony64 there are many primitive characteristics in the brain of the Neanderthals. The front of the forebrain, the so-called prefrontal area, which is the seat of the higher faculties, is not fully developed but has a protuberance as in the brain of the anthropoids. The left frontal lobe in particular, which is associated with the power of speech, is not much developed in the lower part, so that a limited development of the faculty of speech is inferred. The lateral fissure of Sylvius is relatively wide and open, and this and other features suggest the brain of the anthropoid. The brain of the skull of La Quina, which is believed to be that of a female, also shows many primitive features.65 The absolute cubic capacity of the brain is less significant of intelligence than the relative development of those portions of the brain which are concerned in the higher processes of the mind.

The stature of the various examples of the Neanderthal race is estimated somewhat differently by Boule and by Manouvrier, and also varies with the sex :

| Neanderthal (Boule) | 1.55 m. | 5 ft. | 1 in. |

| “ (Manouvrier) | 1.632 m. | 5 ft. 4 1/5 in. | |

| La Chapelle (Boule) | 1.57 m. | 5 ft. | 1 4/5 in. |

| “ (Manouvrier) | 1.611 m. | 5 ft. | 3 2/5 in. |

| Spy (Manouvrier) | 1.633 m. | 5 ft. | 4 3/10 in. |

| La Ferrassie I (Manouvrier) | 1.657 m. | 5 ft. | 5 1/5 in. |

| Average of Neanderthals supposed male | 1.633 m. | 5 ft. | 4 3/10 in. |

| La Ferrassie II (female) | 1.482 m. | 4 ft. | 10 3/10 in. |

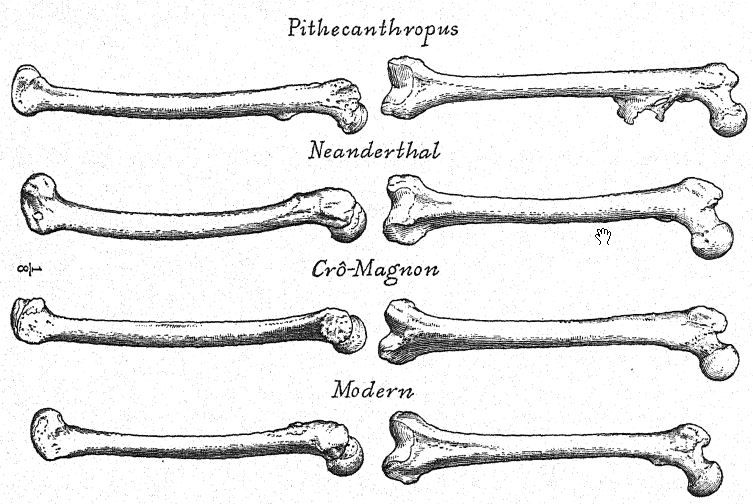

The Neanderthal head is very large in proportion to the short, thick-set body, which we observe rarely exceeds 5 feet 5 inches in height in the male, and 4 feet 10 inches in the female. The proportions of the body and limbs of the Neanderthals throw a surprising light on their ancestral history as well as upon their defects as a race dependent upon the chase. In proportion to the length of the thigh, the lower leg is much shorter than in any existing human race. The tibia or shin-bone is only 76.6 percent [ p. 238 ] of the length of the femur or thigh-bone, whereas in the existing races with the shortest shin-bone, such as the Eskimos and the majority of the yellow races, it is never less than 80 per cent of the length of the thigh-bone. In this respect the Neanderthal man is not like the anthropoid apes but has a relatively shorter shin-bone, because the gorillas have an index of 80.6 per cent, the chimpanzees of 82 per cent, the orangs and gibbons of above 83 per cent; thus all the anthropoid apes and the lower races of man have a relatively longer leg from the knee down than has the Neanderthal race.

The shortness of the shin-bone as compared with the length of the thigh-bone is proof that the Neanderthals were very clumsy and slow of foot, because this proportion is characteristic of all slow-moving animals, whereas a long shin-bone and a short thigh-bone indicate that a race is naturally fleet of foot.

Similarly the Neanderthal man has a very short forearm, only 73.8 per cent of the upper arm ; it approaches the proportions seen in the Eskimos, Lapps, and Bushmen.66 Here, again, the Neanderthal man, differs from the anthropoid apes, among which the shortest forearm is that of the gorilla, having a ratio of 80 per cent.

There are other features which would tend to show that the ancestors of the Neanderthaloids had been ground dwellers rather than tree dwellers back into a very remote period of geologic time; the arms are much shorter than the legs, whereas in tree dwellers [ p. 239 ] they are much longer. Thus, we have observed in the anthropoid apes that the arm is very long in proportion to the leg; in the chimpanzee, which has relatively the shortest arms among the anthropoid apes, the index is 104 per cent, that is, the arms are shghtly longer than the legs. On the contrary, in the Neanderthals the arm length is only 68 per cent of the leg length ; thus it is very far removed from the anthropoid-ape type and comes nearest to the Australian and African negro types.

Thus, to sum up the bodily proportions of the Neanderthals :