[ p. 107 ]

ARRIVAL OF THE PRE-CHELLEAN FLINT WORKERS DUMNG THE THIRD INTERGLACIAL — GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND THE RIVER DRIFTS — PRE-CHELLEAN FLINT INDUSTRY — THE PILTDOWN RACE — MAMMALIAN LIFE — CHELLEAN AND ACHEULEAN INDUSTRIES — THE USE OF FIRE — THE SECOND PERIOD OF ARID CLIMATE — THE NEANDERTH.VL RACE OF KRAPINA, CROATIA

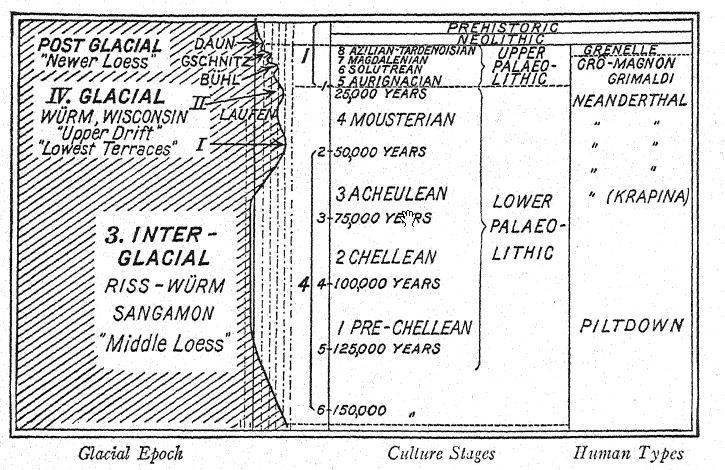

The geologic epoch of the arrival of the Pre-Chellean flint workers in western Europe is by far the most important and interesting one before the prehistorian. Upon it depends the question of the duration of the Old Stone Age, the date of appearance of the Piltdown and of the Neanderthal races, and the whole sequence of climatic and geographic changes surrounding the early history of man. After weighing all the evidence very carefully, the balance of opinion seems to sustain the view that this epoch should be placed after the close of the third glaciation and before the advent of the fourth, that is, during the Third Interglacial Stage.

Penck estimated that the third warm interglacial stage* opened about 100,000 years ago and lasted between 50,000 and 60,000 years. According to the theory that we have adopted in this work, the Third Interglacial and Fourth Glacial embraced the entire period of Lower Palaeolithic time, a period of from 70,000 to 100,000 years, much longer than that of Upper Palaeolithic time, which is estimated at 16,000 to 25,000 years.

¶ Geologic Antiquity of the Beginning of the Stone Age

Attention should first be called to the fact that, preceding the epoch we have now entered, the glacial and interglacial forces [ p. 108 ] operating over the great peninsula of western Europe had left their impress chiefly on the glaciated areas and only to a minor degree on the free, non-glaciated areas. Until toward the close of Third Interglacial times no traces of northern much less of arctic forests and animals are discovered anywhere, except along the borders of the ice-fields. It would appear as if the animal and plant life of Europe were, in the main, but slightly affected by the first three glaciations. We cannot entertain for a moment the belief that in glacial times all the warm flora and fauna migrated southward and then returned, because there is not a shred of evidence for this theory. It is far more in accord with the known facts to believe that all the southern and eastern forms of life had become very hardy, for we know how readily animals now living in the warm earth belts are acclimatized to northern conditions.

¶ Glacial Epoch Culture Stages Human Types

If, on the other hand, we depend solely on the testimony of the life conditions, we might conclude that the Pre-Chellean flint workers reached western Europe either in Second Interglacial [ p. 109 ] times, or during the third glaciation, or again during Third Interglacial times. Let us consider this evidence of the fossil mammals more closely.

In favor of the theory that the Pre-Chellean culture is as ancient as Second Interglacial times, we should consider the fact that in several localities palasoliths of Pre-Chellean if not of Chellean type have been recorded in association with the remains of a number of the more primitive mammals which we have described above as characteristic of Second Interglacial times. For example, at Torralba, Province of Soria, Spain, there has been discovered1 an old typical Chellean camp site, containing abundant remains of the broad-nosed rhinoceros and of the southern mammoth, mingled with the remains of other mammals of very ancient type, identified as the Etruscan rhinoceros and as [ p. 110 ] Steno’s horse. Again, along the River Somme, near Abbeville, in the gisement du Champ de Mars,2 it is said that Pre-Chellean and Ghehean implements have been found in association with the Etruscan rhinoceros, Steno’s horse, and very numerous specimens of the sabre-tooth tiger and of the striped hyaena. Moreover, in Piltdown, Sussex, Pre-Chellean flints and the Piltdown skull are said to have occurred in a layer containing a rhinoceros which may be identified with the Etruscan. If these very ancient species of animals are rightly recognized and determined, and if they are truly found as reported in close association in the same layers with Pre-Chellean and Chellean flints, the evidence may [ p. 111 ] be considered as quite strong that the beginning of Chellean culture dates from Second Interglacial times; unless, indeed, it should prove that these primitive species of mammals survived into Third Interglacial times in certain favored districts. We should also consider the possibility that these more ancient animals, the sabre-tooth tiger, Steno’s horse, the Etruscan rhinoceros, and the giant beaver, did not really belong in the same layer with these old palasoliths but were accidentally washed into this layer from other more ancient deposits. As a rule, it is the most recent animals which establish a prehistoric date, because we know that a palaeolith cannot be older than the most recent mammal with which it occurs.

The record of the three early glaciations is not fully written in the animal and plant life, but it appears to be found in the river channels. Both in England and France these channels attest flooded conditions during the earlier glaciations, in which large [ p. 112 ] quantities of gravels and sands were transported, and it is of these materials that the ‘high terraces’ were built up, It is chiefly the geologic evidence which establishes the Pre-Chellean date.

Geologic and climatic lines of evidence in France indicate that the Pre-Chellean culture is first witnessed during the beginning of Third Interglacial times. This is the opinion of Boule, Haug, Obermaier, Breuil, Schmidt, and many other geologists and archaeologists. That the first Palaeolithic flint workers found their way into western Europe during the early part of Third Interglacial times is consistent with our observations on the sequence of climate, on the formation of the ‘low river terraces,’ where palaeoliths of the earliest type occur, as well as with the general succession of mammalian life throughout the climatic changes of this interglacial period. It would appear, in explanation of the facts cited above regarding the fossil mammals, that when the Pre-Chellean flint workers established their camps along the valley of the River Somme in northern France a very genial climate prevailed in this region, favorable even, as we shall see, to the survival of some of the Pliocene types of mammals, such as the sabre-tooth tiger and the Etruscan rhinoceros.

During the early part of the Third Interglacial Stage the climate, so far as we can judge by the unchanged aspect of the animal life, remained of the same warm temperate character. Two only of the surviving Pliocene forms, namely, the sabretooth tigers and the Etruscan rhinoceroses, became rare or extinct. From evidence afforded in Kent’s Hole, Devonshire, Dawkins is led to believe that the sabre-tooth tiger survived in Britain until Postglacial times. AU the rest of the animal world, both the African-Asiatic and the Eurasiatic mammals, continued to flourish throughout western Europe.

Not until the latter part of Acheulean times do we discover proofs of a decided change of climate; in the approach of arid conditions similar to those of the steppes of western Asia there was a renewal of the great dust-storms and depositions of ‘loess,’ such as had previously occurred toward the close of Second Interglacial times ; this was followed by the still colder climate of the [ p. 113 ] fourth glaciation, which corresponds with the closing period of Lower Pahcolithic culture.

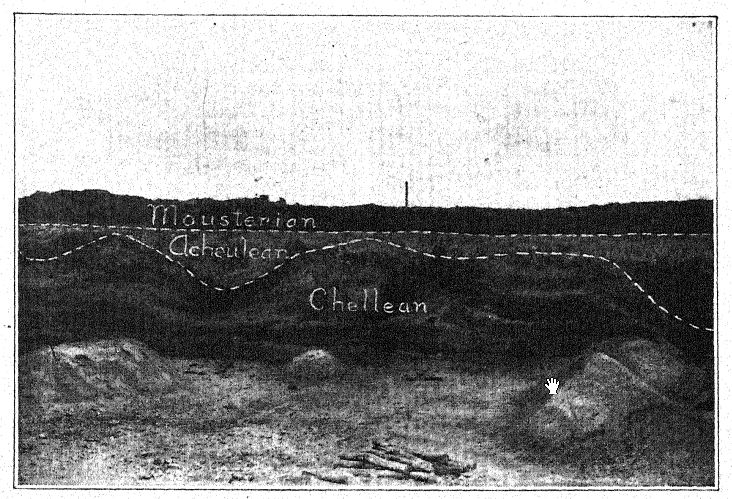

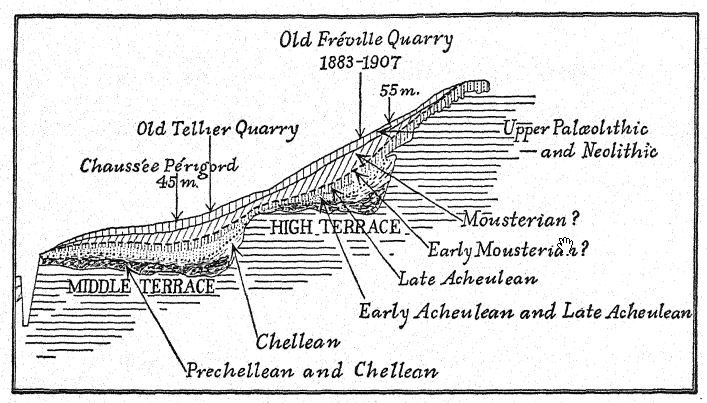

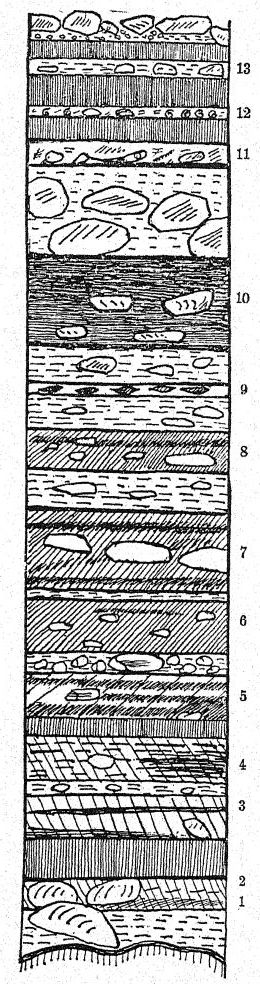

The evolution of the Pre-Chellean into the Chellean and finally into the Lower Acheulean palaeoliths certainly occupied a very long period of time if we assign it merely the 50,000 or 60,000 years allotted to the Third Interglacial; but even this allotment seems far too long when we observe the relatively limited depth of the river deposits in which these flint cultures succeed each other. For we cannot fail to be impressed by the regular and very close and unbroken succession of the geologic layers containing the Chellean and Acheulean artifacts. (See Fig. 55.)

None the less it follows that a long lapse of time must be allowed for each culture period, and for the advance in technique.3 It is this wide distribution that has enabled the de MortiUets (father and son), Capitan, Riviere, Reboux, Daleau, Peyrony, Obermaier, Commont, Schmidt, and others to establish in various parts of Europe the main stages of the industrial evolution of the Old Stone Age, or Lower Palaeolithic.

¶ Subdivisions of the Lower Palaeolithic Cultures4

MOUSTERIAN. Late industry of the Neanderthal races. Extensive use of the ‘flake.’

- Late Mousterian. La Quina scrapers, small ‘coups de poing,’ and bone anvils, closing with the Abri Audit culture.

- Middle Mousterian. Culmination of the Mousterian ‘point’ finely flaked and chipped on one side, the best examples approaching the Solutrean perfection of technique.

- Early Mousterian. Heart-shaped ‘coups de poing’ and Mousterian flake ‘points’ and flake scrapers.

ACHEULEAN. Early industry of the Neanderthal races. Extensive use of the nodular core.

- Late Acheulean. Miniature ‘lance points’ of La Micoque type, triangular ‘coups de poing,’ and flint flakes of Levallois type.

- Middle Acheulean. Pointed oval ‘coups de poing,’ much lighter than the Chellean types, and small implements similar to the Chellean but much improved in workmanship.

- Early Acheulean. Broad oval ‘coups de poing’ much more symmetrical than the Chellean but still rather heavy. Small types.

[ p. 114 ]

CHELLEAN.

- Late Chellean. Long pointed ‘coups de poing,’ in niost cases flaked on both sides, with little of the crust of the nodule adhering and the edges still unsymmetricai. First appearance of the oval ‘coups de poing.’

- Early Chellean. First appearance of ‘coups de poing’ of almond shape. Small implements, including scrapers, planes, and borers. All implements unsymmetricai and with uneven edges.

- Pre-Cheelean. Probable industry of the Piltdown and of the (PreNeanderthaloid) Heidelberg races. Use of chance and accidental forms. Forms partly accidental; retouch limited to the few strokes necessary to give a point or edge to the tool, or to allow a Arm grasp (protective retouch). Prototypes of ‘coup de poing’ formed of flint nodules with crust only partially removed.

If we suppose that the Pre-Chellean flint workers arrived in Europe not earlier than Third Interglacial times, we can explain all the gradations in the evolution of their implements in connection with the changes of climate and of animal life which the geologic and fossil deposits reveal, especially in the valleys of the Somme and of the Thames.

If, on the other hand, the Pre-Chellean is dated in Second Interglacial times,[2] it carries this culture back another hundred thousand years and involves our prehistory in great difficulties. First, there is no proof whatever that the Pre-Chellean and Chellean flint workers lived during the period of the formation o’f the ‘high river terraces’ of the third glaciation, for no Palaeolithic flints have ever been foimd buried in the sands or gravels of the ‘high terraces.’ The occurrence of archaic flints on the ‘high terraces’ of the Somme and of the Seine is in superficial gravel beds which were deposited long after these ‘terraces’ had been cut by river action ; this is best seen in the Somme, where archaic flints occur alike in the gravels deposited upon the ‘low,’ ‘middle,’ and ,‘high terraces.’ Second, there is no proof that the Pre-Chellean and Chellean fliint workers passed through the cold climatic period of the third glaciation ; nowhere in Europe have [ p. 115 ] any records been found of their camps or stations in association with the cold fauna or flora of Third Glacial times. Third, the geographical evidence is equally at variance with the theory that the Pre-Chellean flint workers entered Europe during the Second Interglacial Stage, for we know positively that in many of the great river-valleys of Europe, especially those surrounding the Alps, the rivers were at much higher levels than at present and that they were transporting the materials out of which the ‘high terraces’ were being formed or cutting these ‘terraces’ down by erosion.

In other words, the geography of Europe in First and Second Interglacial times was very different from what it is at present; most of the river-valleys were broader and less deep; some of them had been eroded to a point below their present levels and had begun to silt up in alluvial deposits. In Third Interglacial times the river geography of Europe was substantially as it is to-day, although the coast-lines were still very different.

When Pre-Chellean man appeared, we shall see that the river-valleys of the Somme and Marne, in northern France, as well as of the Thames, in southeastern England, were closely similar to what they are at present in respect to their waterlevels; in other words, the inland geography of Europe in the north in Chellean times and in central and southern France in the immediately succeeding Acheulean times was very much like it is at present. The superficial characters of the valleys were different ; the streams in Chellean times flowed through gravels and sands, partaking of a glacial aspect ; one or more of the ‘river terraces’ composed of sands and gravels were still sharply defined, for the soft covering of ‘loam’ and alluvial soil from the surrounding uplands and hills had not yet washed dowm to soften the outlines of the ‘terraces.’ Neither were the ‘terraces’ covered with the newer deposits of ‘loess.’

[ p. 116 ]

[ p. 117 ]

¶ Secular Changes of Climate in Lower Palaeolithic Times

We find evidences of four climatic and life phases during the long period of Lower Paheolithic evolution, as follows:

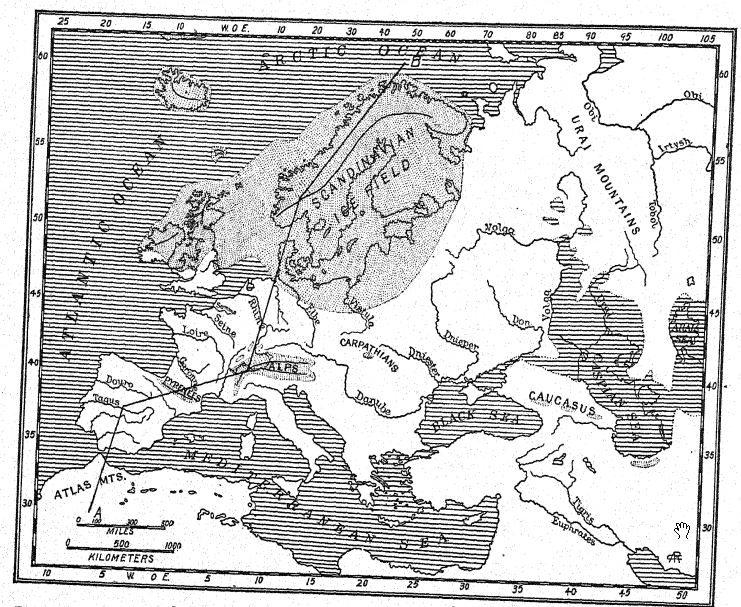

4. Cold Moist Climate.—Advent of the fourth glaciation. Arrival of the ‘full Mousterian’ culture and of the Neanderthal race in Beigium and France. Repair of men to the warmer shelters, grottos, and entrances to the caverns. Final disappearance of the hardy Merck’s rhinoceros and the straight-tusked elephant. Arrival of the tundra fauna, the reindeer, the woolly mammoth, and the woolly rhinoceros. Refrigeration of western Europe as far south as northern Spain and Italy. Wide distribution of cold alpine, tundra, and steppe mammals all over Germany and France, and into northern Spain. Cold tundra flora in the Thames valley, and at Hoxne, in Suffolk. Migration of the tundra mammals, the reindeer, mammoth, and rhinoceros all over southern Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, and Austria.

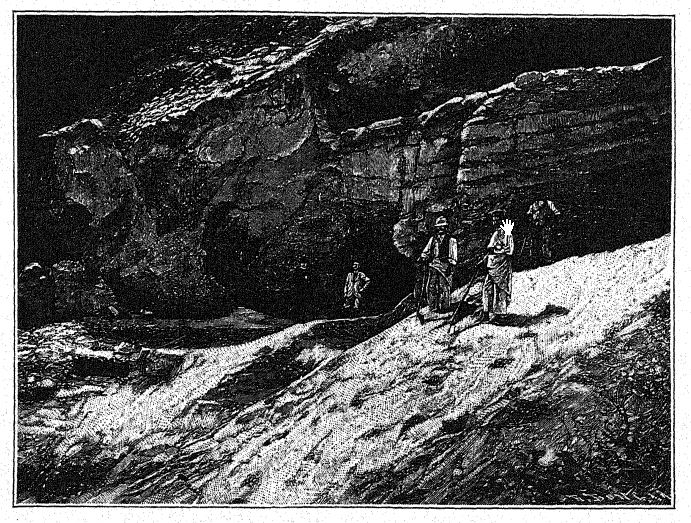

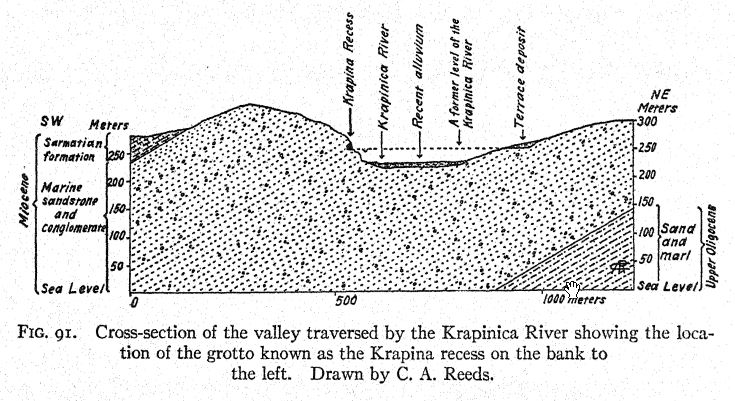

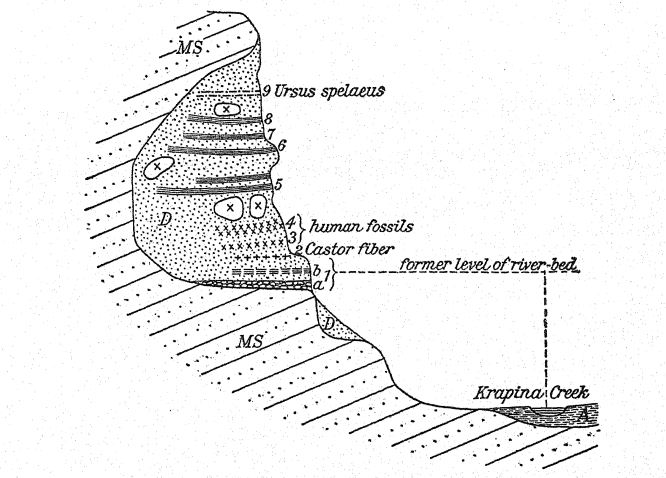

3. Arid Climate in Western Europe.—Period of the close of the Acheulean culture ; some of the flint workers seeking the shelter of cliffs and approaching the entrances to the grottos during the cold season of the year. A dry steppe climate, prevailing westerly winds, and deposits of ‘loess’ all over northern France and Germany. Appearance of the first Neanderthaloid men in Krapina, Croatia. Cool forest flora in the region of La Celle-sous-Moret near Paris, followed by depositions of ‘loess’ and increasingly cool and arid climate. Early Mousterian industry. Disappearance first of the more sensitive pair of Asiatic mammals, the hippopotamus and the southern mammoth (E. trogontherii) ; persistence of the more hardy, straight-tusked elephant (E_. antiquus_) and the broad-nosed rhinoceros (D. merckii).

2. Continued Warm Temperate Period.—Time of the Chellean culture found at Chelles, St. Acheul, Gray’s Thurrock, Ilford, Essex, and southward in Torralba, Spain. Abundance of hippopotami, rhinoceroses, southern mammoths, and straight-tusked elephants in northern Germany at Taubach, Weimar, Ehringsdorf, and Achenheim. Rare appearance of sabre-tooth tigers. Temperate forest and alpine flora of Dürnten and Utznach, Switzerland. Early Acheulean culture widely distributed over all of western Europe.

1. Early Warm Temperate Period.— The warm climate of the Pre-Chellean culture period, as seen in the valleys of the Somme, of the Thames, and of the Seine near Paris, favorable to the southern mammoth and the hippopotamus. Apparent survival of the sabre-tooth tiger and the Etruscan rhinoceros in favored regions. A warm temperate forest flora in. La Celle-sous-Moret near Paris and in Lorraine. Arrival of the Pre-Chellean flint workers and of the Piltdowh race in southern England.

[ p. 118 ]

It is believed that the climate of Third Interglacial times when it reached its maximum warmth was again somewhat milder than the present climate in the same region. In the Alps the glaciers and the snow-line retreated once more to their present levels. The period opened with humid continental conditions. The areas left bare by the ice were gradually reforested. A picture of the climate in this warm period is presented in the region near Paris in the so-called tuf de La Celle-sous-Moret (Seine-et-Marne). This tufa, which is a hot-springs deposit, overlies river-gravels of Pleistocene age.7 The lower levels of the tufa contain the sycamore-maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) , willows, and the Austrian pine, indicating a temperate climate. Higher up in the same deposits we find evidences of increasingly mild temperatures in the presence of the box (Buxus) and not infrequently of the fig-tree ; the Canary laurel (Laurus nobilis) is somewhat rarer and both it and the fig indicate that the winters were mild, because these plants have the peculiarity of flowering during the winter season ; we infer, therefore, that the climate was somewhat milder and more damp than it is in the same region at the present time. T^he mollusks also indicate greater equability of climate. These deposits are believed to correspond with the period of Chellean and early Acheulean industry.

The plants in the highest levels of the same tufa, however, indicate the advent of a colder climate and also connect this with the Acherdean culture stage through the presence of ikcheulean flints. The deposit of tufa is covered by a sheet of ‘loess’ corresponding with the return of an arid period in late Acheulean times, in the very heart of northern France. Thus we have a record in the region near the present city of Paris of three climatic phases, which are also more or less completely indicated in deposits to the north along the River Somme and in the valley of the ancient Thames.

In western France we again interpret the fossil flora of Lorraine as belonging to the cooler closing period of Third Interglacial [ p. 119 ] times and to the advent of the fourth glaciation, for here the most northern varieties of the larch (Larix) and of the mountain-pine (Pinus lambertiana) predominate.

The clearest view of the contemporary alpine forests is found near Zürich in the hgnitic deposits of Dürnten and of Utznach, which are so characteristic of the temperate period of the Third Interglacial Stage that Geikie has proposed to call this stage the Durntenian.8 It was, we recall, at Dürnten that Morlot9 found the first proofs of a warm or temperate interglacial flora, between the deposits of a retreating glacier and those of an advancing glacier ; for Dürnten is well within the region which was covered by the vast ice-fields both of the third and fourth glaciations. The forests which flourished there in Third Interglacial times were similar to those now found in the same region, consisting of the spruce, fir, mountain-pine, larch, beech, yew, and sycamore, with undergrowth of hazel. With this hardy flora are associated the remains of the straight-tusked elephant, of Merck’s rhinoceros, of wild cattle, and of the stag ; another evidence for our opinion that all these Asiatic mammals had become habituated to the cool temperate climate of the north.

¶ Life om the River Somme from Pre-Chellean to Neolithic Times

The borders of the River Somme at St. Acheul give us a vista of the whole story of the succession of geologic events; the great changes of climate, the procession of animal life, the sequence of human races and cultures. Here Commont10 has found the key to the history of this entire country and enabled us to parallel events here with those occurring far away in Taubach, on the borders of the Thuringian forest, and at Krems in Lower Austria, as studied by Obermaier, This is because the ‘older’ and ‘newer’ loess periods, the succession of climates and of mammals, and the development of human cultures were all not local but continental events. The purely local events are found in the kinds of gravels and soils which washed down over the terraces.

[ p. 120 ]

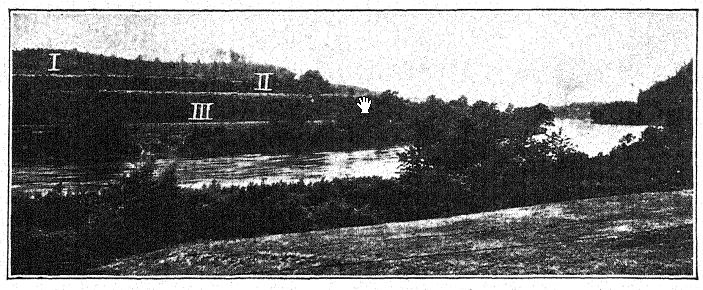

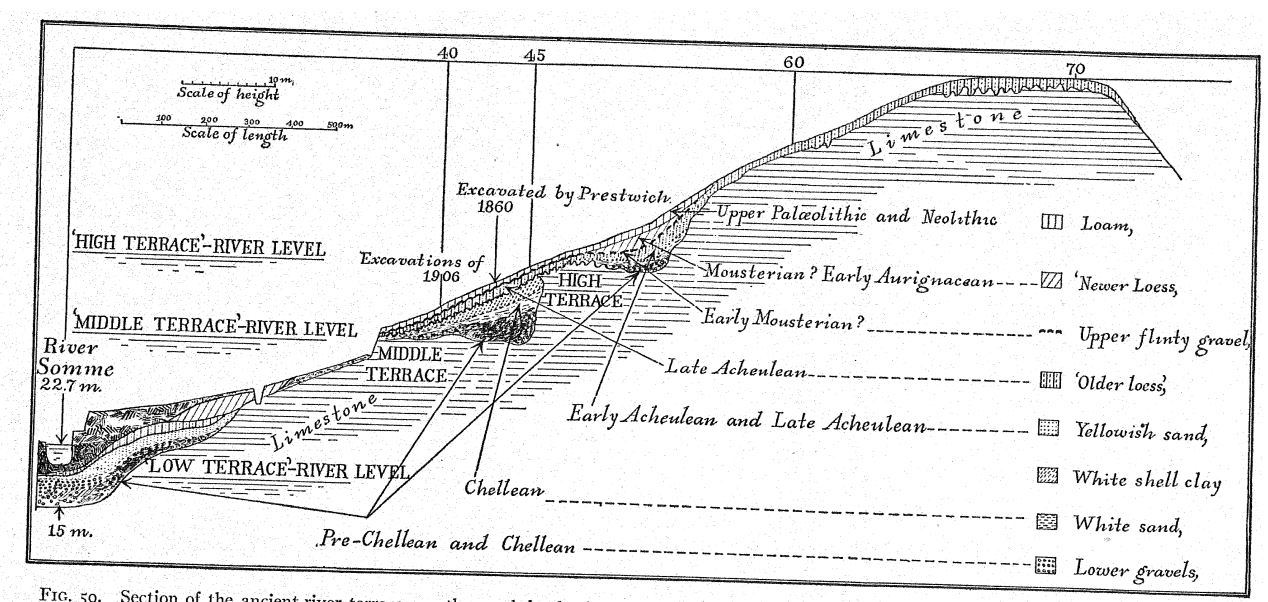

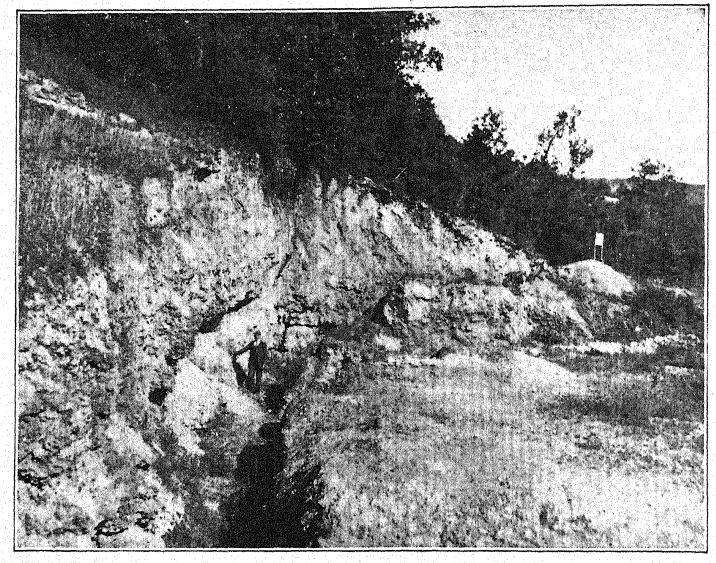

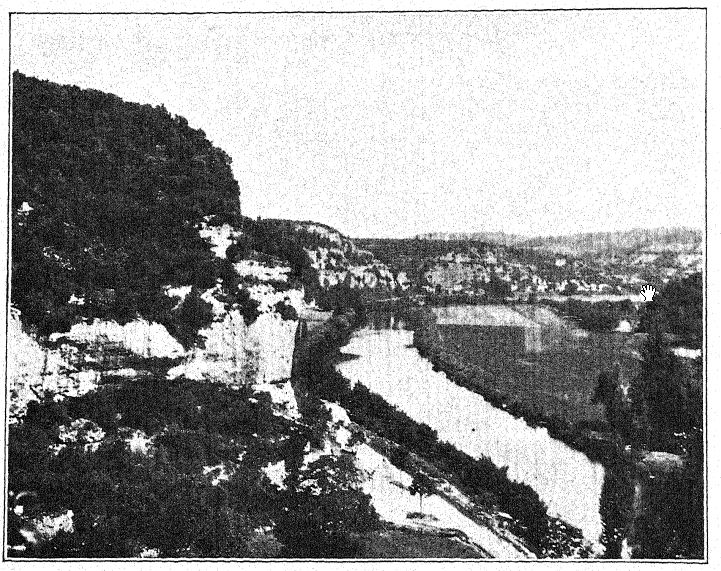

It is very important first to clearly picture in our minds and understand the geography of the Somme at the time of the arrival of the Pre-Chellean flint workers. It appears certain that all three of the old river terraces composed of limestone had been cut long before and that the river had already reached the bottom level of the underlying chalk rock.11 The higher terrace, then as now, was loo feet above the Somme, the middle terrace about 70 feet, and the lowest terrace extended from a height qf about 40 feet down underneath the present river level (see Fig. 59).

Since the most primitive Pre-Chellean flints occur in the coarse gravels which lie on the floors of these terraces immediately above the chalk, they prove that the entire excavation of the valley had been completed when the Pre-Chellean workers arrived there. Commont believes that this was the actual topography of the valley during the Third Interglacial Stage. The occurrence of Chellean flints in the white sands overlying the coarse gravels of the middle and upper terraces does not indicate that the flint workers were encamped here while these terraces were being cut out by the River Somme but rather that they sought these convenient bluffs for their quarries during the time that these sands and gravels were washing down from the sides of the valleys and from the plateaus above.

[ p. 121 ]

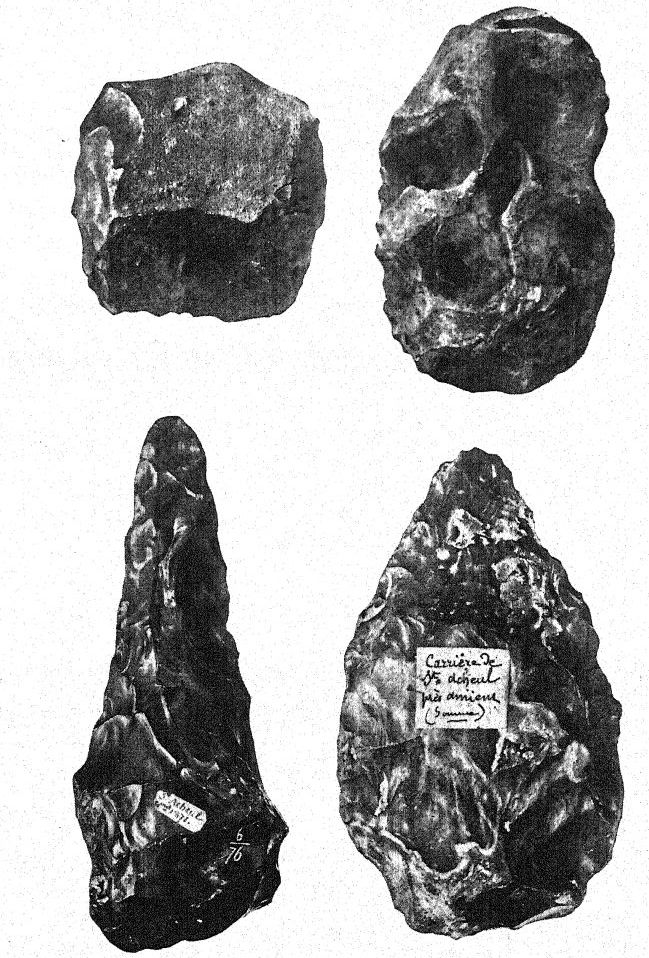

a. Disc-shaped—iipper left. c. Poniard-shaped—lower left.

b. Oval— upper right. d. Almond-shaped— lower rights

In the collection of the American Museum of Natural History.

[ p. 122 ]

[ p. 123 ]

The history of the climatic changes in the ancient valley of the Somme is most clearly written in these successive deposits, 15 feet in thickness, above the Tower gravels’ at St. Acheul. Along with the Pre-Chellean and Chellean flints in the ‘old gravels’ and ‘white sands’ we find records of the moist warm temperate climate which then prevailed in northern France and which undoubtedly was most favorable to the hippopotami, rhinoceroses, and elephants of those times. The river mollusks found with the late Chellean flints are another indication of the temperate forest climate which continued through early Acheulean times.

In the middle Acheulean are found the earliest deposits of ‘older loess’ which indicate a climate still temperate but arid, belonging to the middle of the Third Interglacial Stage. In Mousterian times we find heavy deposits of gravels corresponding to the moist cold climate of the Fourth Glacial Stage, followed in middle Aurignacian times by fresh layers of ‘newer loess,’ indicating the return of a dry climate. Finally, the layers of loam which were washed down over the sides of the valley, and in which the remains of Solutrean and Aurignacian camps are found, indicate the renewal of moist and probably forested conditions.

Thus, two dry loess periods are indicated in this valley, the first or ‘older loess’ belonging to Third Interglacial times, and the second or ‘newer loess’ to Postglacial times; and we clearly perceive that in the culture layers here there is no evidence what [ p. 124 ] ever of more than one glacial stage preceded by a dry climatic period and deposits of loess. If the Pre-Chellean flint workers had arrived in this river- valley as early as Second Interglacial times, we should find proofs of three periods of arid climate and loess deposition and of two glaciations.

PREHISTORY OF ST. ACHEUL

- NEOLITHIC.

- Campignian, recent earth and loam.

- UPPER PALAEOLITHIC.

- Solutreau.

- Upper Aurignacian, loam.

- Middle Aurignacian, ‘newer loess’ and gravel.

- LOWER PALAEOLITHIC.

- Late Mousterian, gravel ‘newer loess.’

- Early Mousterian, base ‘newer loess’ (l’ergeron).

- Middle Acheulean, ‘older loess’ and drift.

- Early Acheulean, gravels below ‘older loess’ (E. anliquus).

- Late Chellean, fluviatile sands and mollusk fauna.

- Early Chellean, first coups de poing; old ‘white sands’ (E. anliquus).

- Pre-Chellean, prototypes of coup de poing; old ‘lower gravels’ (E. anliquus).

Beginning with middle Acheulean times the flints are found in deposits of gravels, loams, brick-earths, and ‘older loess,’ which all belong to a succeeding geologic stage and are of more recent date than the lower gravels and sands on the terraces which they overlap and conceal. Deposits of this kind have also been drifted dowm from the highest levels toward the bottom of the valley, and Commont distingmshes three different depositions or layers of ‘loess loam,’ the lowest or oldest of which contain Acheulean flints, while the middle loams contain Mousterian implements.

Even toward the close of the Third Interglacial Stage there were periods of warmth, perhaps during the height of the hot summer season, when animals of the warm fauna migrated from the south. Thus Commont has recently discovered in the valley of the Somme a station of Mousterian flint workers, whose industry is associated with remains of the three animals typical of the warmer climatic phase; namely, the straight-tusked elephant, the broad-nosed rhinoceros, and the hippopotamus. He has reafirmed his belief that the greater part of this chapter of human prehistory, both as to the surface topography of the Somme valley and the evolution of the flint cultures from Pre-Chellean to Mousterian times, occurred during the Third Interglacial Stage.

¶ The Early Warm Temperate Period of the Pre-Chellean Culture

We have observed that from Torralba in the Province of Soria, Spain, to Abbeville, near the mouth of the Somme, in the north of France, three types of animals which entered Europe as [ p. 125 ] early as Upper Pliocene times, namely, the Etruscan rhinoceros, the horse of Steno, and the sabre-tooth tiger, are said to occur in connection with early Chellean artifacts. The two former species may possibly be confused with early forms of Merck’s rhinoceros and the true forest horses of Europe, but there can be no question as to the identification of the sabre-tooth tiger, numbers of which were found by M. d’Ault du Mesnil, at Abbeville, on the Somme, with early Chellean flints.

The mammalian life of the Somme at this time, as found in the gisement du Champ de Mars near Abbeville, is very rich.

Among the larger forms there is certainly the great southern mammoth (E. meridionalis trogontherii) , and possibly also the straight-tusked elephant (E. antiquus). There are unquestionably two species of rhinoceros, the smaller of which is recognized by Boule as the Etruscan, and the larger as Merck’s rhinoceros. Steno’s horse is said to occur here, and there are abundant remains of the great hippopotamus (H. major) ; the sabre-tooth tigers were very numerous as attested by the discovery of the lower jaws of thirty or more individuals. The short-faced hysena (H. hrevirostris) is also found, and there are several species of deer and mid cattle.

This remarkably rich coUeetion of mammals is associated with flints of primitive Chellean or, possibly, of Pre-Chellean type.^^ In Torralba, Spain, the same very ancient animals occur, and it appears possible that this was the prevailing mammalian life of Pre-Chellean times.

We may conclude, therefore, that there is considerable evidence, although not as yet quite convincing, that the early Chellean flint workers arrived in western Europe before the disappearance of the Etruscan rhinoceros and the sabre-tooth tiger.

Pre-Chellean Fauna

- Southern mammoth.

- Etruscan rhinoceros.

- Hippopotamus.

- Primitive horse (Equus stenonis) ?

- Sabre-tooth tiger.

- Broad-nosed rhinoceros.

- Straight-tusked elephant.

- Giant beaver (Trogontherium cuvieri) .

- Short-faced hysena.

- Typical Eurasiatic forest and meadow fauna, including deer, bison, and wild cattle.

[ p. 126 ]

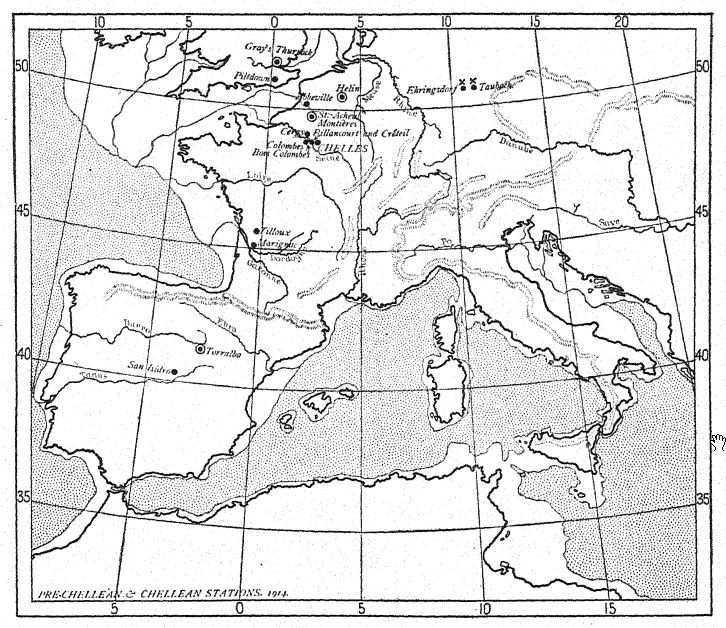

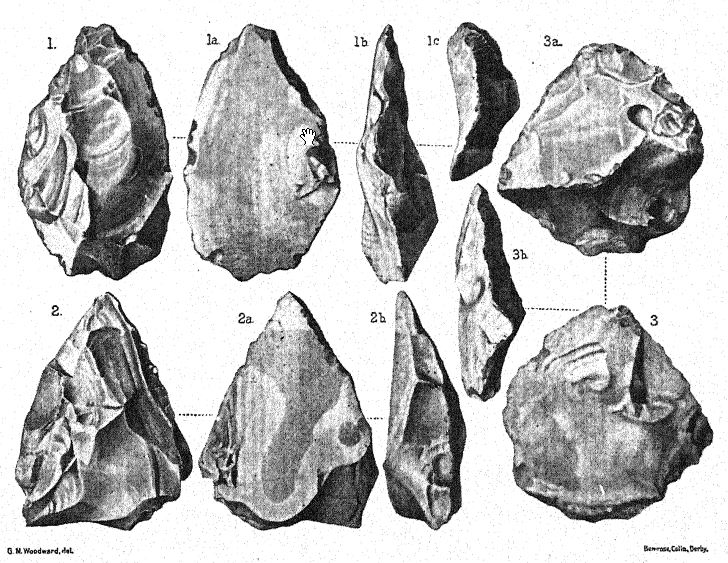

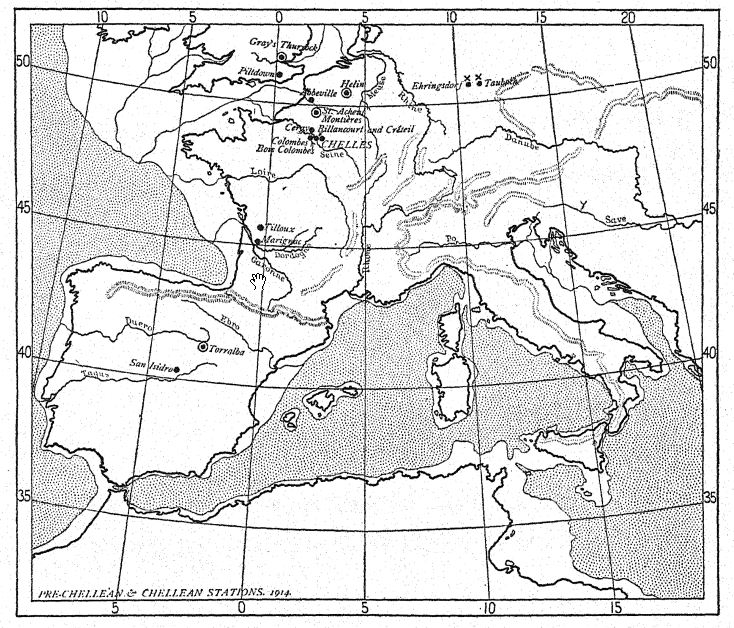

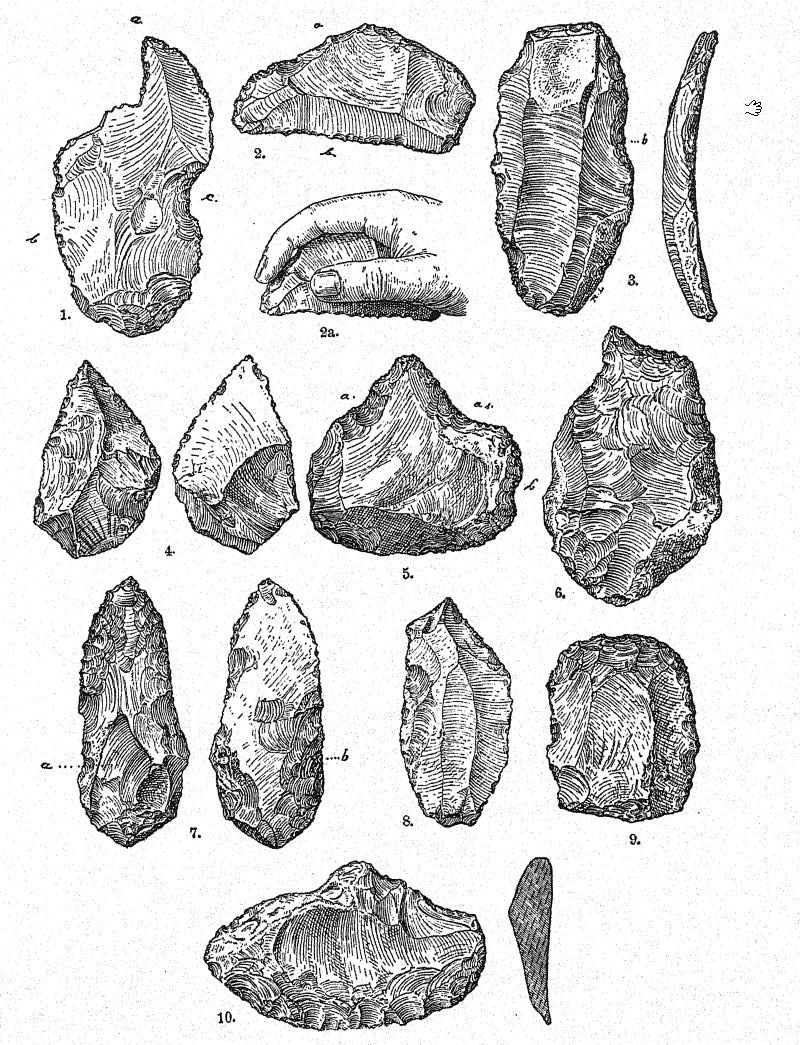

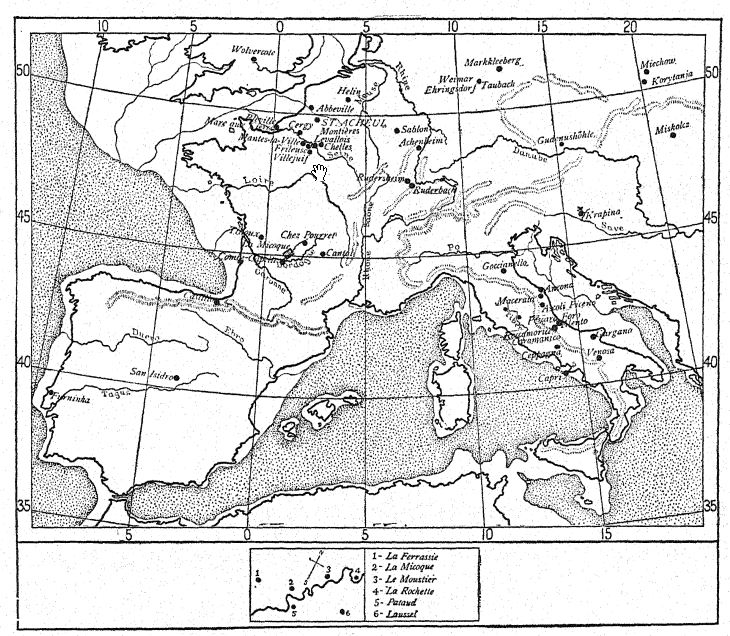

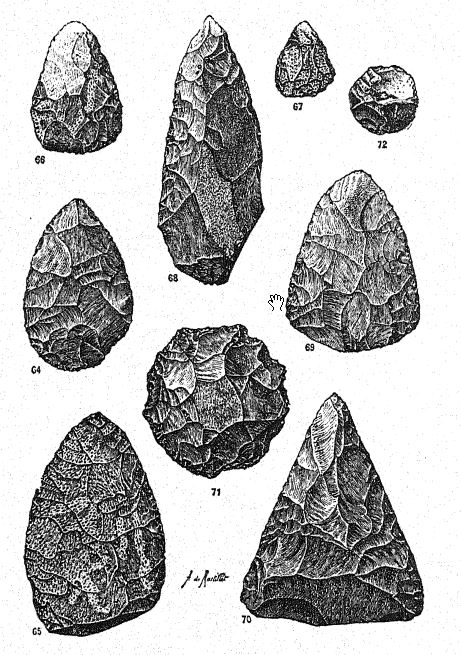

¶ The Pre-Chellean Stations (See Figs. 53 and 56.)

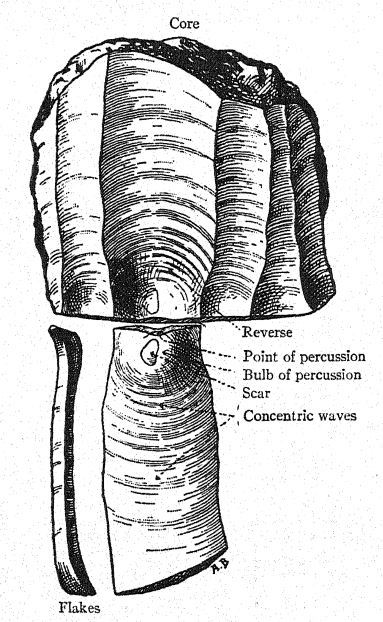

The dawn of the Palaeolithic Age is indicated in various riverdrift stations by the appearance of crude flint weapons as well as tools or implements, in addition to the supposed tools of Eolithic times. There is an unmistakable effort to fashion the flint into a definite shape to serve a definite purpose: there can no longer be any question of human handiwork. Thus there gradually arise various types of flints, each of which undergoes its own evolution into a more perfect form. Naturally, the workers at some stations were more adept and inventive than at others. Nevertheless, the primitive stages of invention and of technique were carried from station to station; and thus for the first time we are enabled to establish the archaeological age of various stations in western Europe.

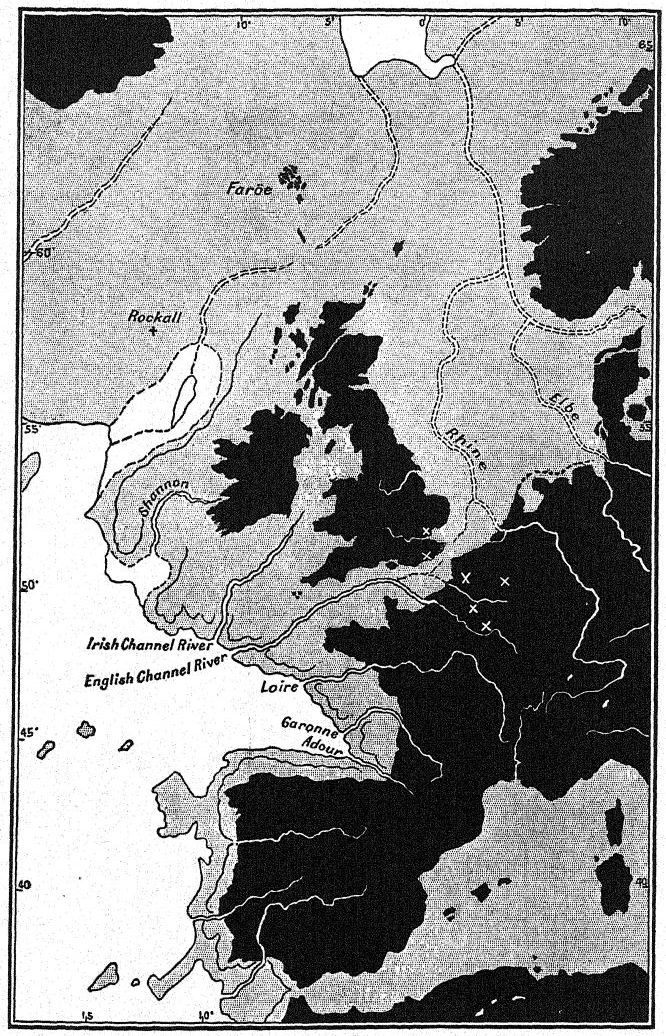

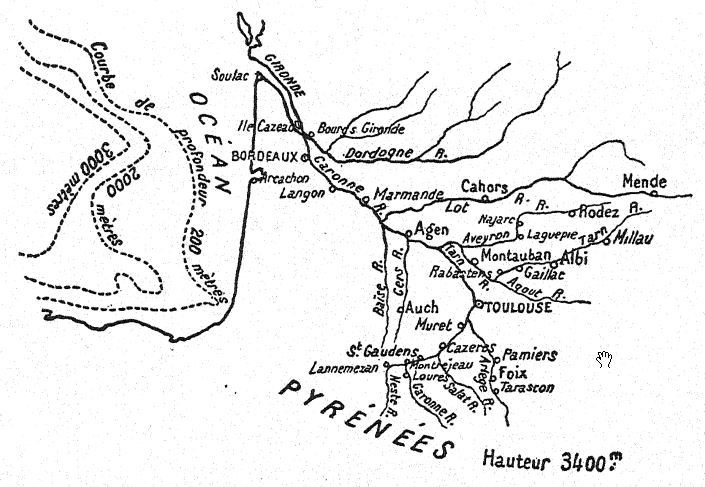

Only a few stations have been discovered where the Palaeolithic men were first fashioning their flints into prototypes of the Chellean and Acheulean forms. With relation to the theory that these primitive flint workers may have entered Europe by way of the northern coast of Africa, we observe that these stations are confined to Spain, southern and northern France, Belgium, and Great Britain. Neither Pre-Chellean nor Chellean stations of unquestioned authenticity have been found in Germany or central Europe, and, so far as present evidence goes, it would appear that the Pre-Chellean culture did not enter Europe directly from the east, or even along the northern coast of the Mediterranean, but rather along the northern coast of Africa,[4] where Chellean culture is recorded in association with mammalian remains belonging to the middle Pleistocene Epoch.

The southernmost stations of Chellean culture at present knowm in Europe are those of Torralba and San Isidro, in central Spain. In the Department of the Gironde is the Chellean station of Marignac, and it is not unlikely that other stations will be discovered [ p. 127 ] in the same region, because the Palaeolithic races strongly favored the valleys of the Dordogne and Garonne, but thus this is the only station known in southern France which represents this period of the dawn of human culture.

The chief Pre-Chellean and Chellean stations were clustered along the valleys of the Somme and Seine. Of those rare sites presenting a typical Pre-Chellean culture, we may note the neighboring stations of St. Acheul and Montieres, both in the suburbs of Amiens on the Somme, and the station of Helin, near Spiennes, in Belgium, explored by Rutot. A very primitive and possibly Pre-Chellean culture was found on the site of the Champ de Mars, at Abbeville. This culture also extended westward across the broad plain which is now the Strait of Dover to the valley of the Thames, on whose northern bank is the important station of [ p. 128 ] Gray’s Thurrock, while farther to the south is the recently discovered site of PiltdowTi, in the valley of the Ouse, Sussex.

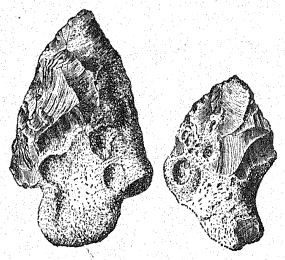

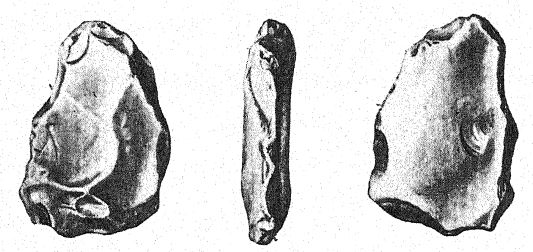

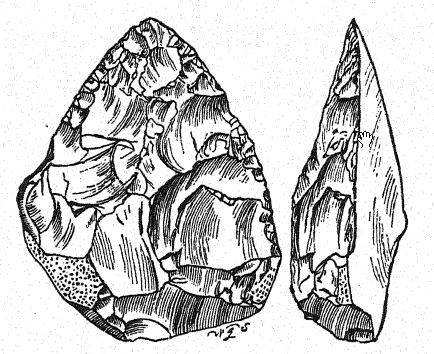

The flint tools (Fig. 60) found in the layer immediately over lying the Piltdown skull are excessively primitive and indicate that the Piltdown flint workers had not attained the stage of craftsmanship described by Commont as ‘Pre-Chellean’ at St. Acheul. “Among the flints,” observes Dawson, “we found several undoubted flint implements besides numerous ‘eoliths.’ The workmanship of the former is similar to that of the Chellean or Pre-Chellean stage; but in the majority of the Piltdown specimens the work appears chiefly on one face of the implements.”

In the Helin quarry near Spiennes13 occur rude prototypes of the Palaeolithic coup de poing associated with numerous flakes which do not greatly differ from those in the lowest river-gravels of St. Acheul; there is a close correspondence in the workmanship of the two sites, so that we may regard the Mesvinian of Rutot[5] as a culture stage equivalent to the Pre-Chellean. The river-gravels and sands of Helin which contain the implements also resemble those of St. Acheul in their order of stratification. Of special interest is the fact that a primitive flint from this Helin quarry, known as the ‘borer,’ is strikingly similar to the ‘Eolithic’ borer found in the same layer with the Piltdown skull in Sussex. By such indications as this, when strengthened by further evidence of the same kind, we may be able eventually to establish the date both of this Pre-Chellean or Mesvinian culture and of the Piltdown race.

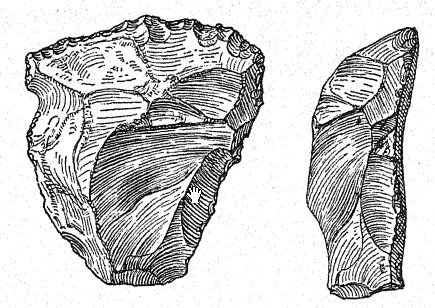

In considering the Pre-Chellean implements found at St. Acheul in 1906, we note14 that at this dawning stage of human [ p. 129 ] invention the flint workers were not deliberately designing the form of their implements but were dealing rather with the chance shapes of shattered blocks of flint, seeking with a few welldirected blows to produce a sharp point or a good cutting edge. This was the beginning of the art of ‘retouch,’ which was done by means of light blows with a second stone instead of the hammer-stone with which the rough flakes were first knocked off. The retouch served a double purpose: Its first and most important object was further to sharpen the point or edge of the tool. This was done by chipping off small flakes from the upper side, so as to give the flint a saw-like edge. Its second object was to protect the hand of the user by blunting any sharp edges or points which might prevent a firm grip of the implement. Often the smooth, rounded end of the flint nodule, with crust intact, is carefully preserved for this purpose (Fig. 61). It is this grasping of the primitive tool by the hand to which the terms ‘coup de poing,’ ‘Faustkeil,’ and ‘hand-axe’ refer. ‘Handstone’ is, perhaps, the most fitting designation in our language, but it appears best to retain the original French designation, coup de poing.

As the shape of the flint is purely due to chance, these Pre-Chellean implements are interpreted by archaeologists chiefly according to the manner of retouch they have received. Already [ p. 130 ] they are adapted to quite a variety of purposes, both as weapons of the chase and for trimming and shaping wooden implements and dressing hides. Thus Obermaier observes that the concave, serrated edges characteristic of some of these implements may well have been used for scraping the bark from branches and smoothing them down into poles; that the rough coups de poing would be well adapted to dividing flesh and dressing hides; that the sharp-pointed fragments could be used as borers, and others that are clumsier and heavier as planes (see Fig. 62).

The inventory of these ancestral Pre-Chellean forms of implements, used in industrial and domestic life, in the chase, and

in war, is as follows :

| Grattoir, | planing tool. |

| Perfoir, | drill, borer. |

| Coutean, | knife. |

| Percuteur, | hammer-stone. |

| Pierre de jet? | throwing stone? |

| Prototyped of coup de poing, | hand-stone. |

It includes five, possibly six, chief types. The true coup de poing, a combination tool of Chellean times, is not yet devel oped in the Pre-Chellean, and the other implements, although similar in form, are more primitive. They are all in an experimental stage of development.

Indications that this primitive industry spread over southeastern England as well, and that a succession of Pre-Chellean into Chellean culture may be demonstrated, occur in connection with the recent discovery of the very ancient Piltdown race.

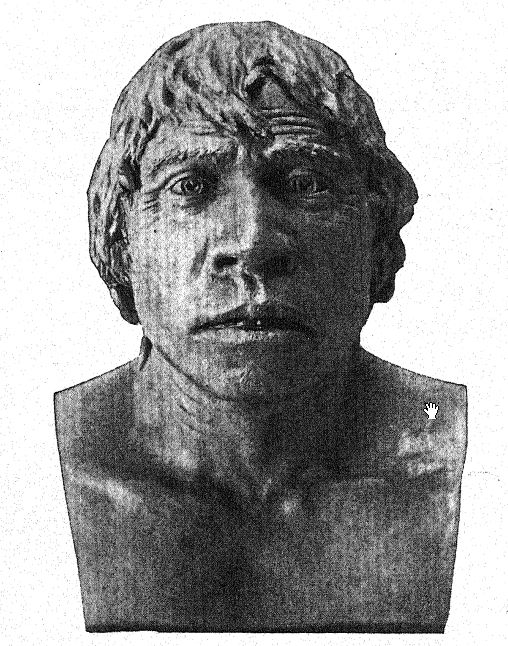

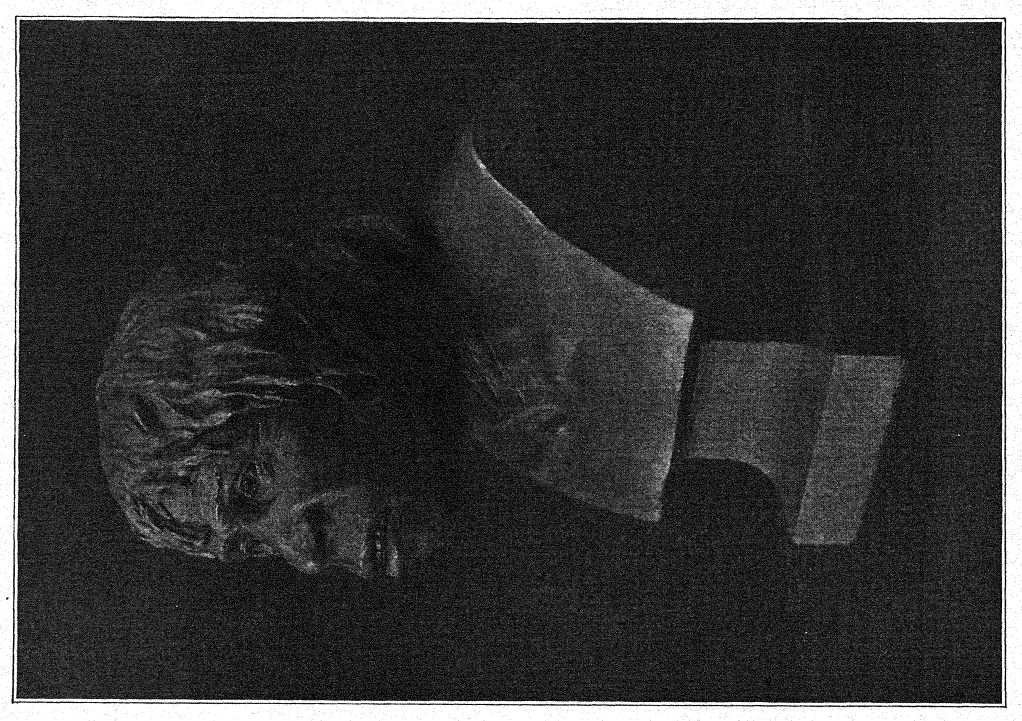

¶ The Piltdown Race 15

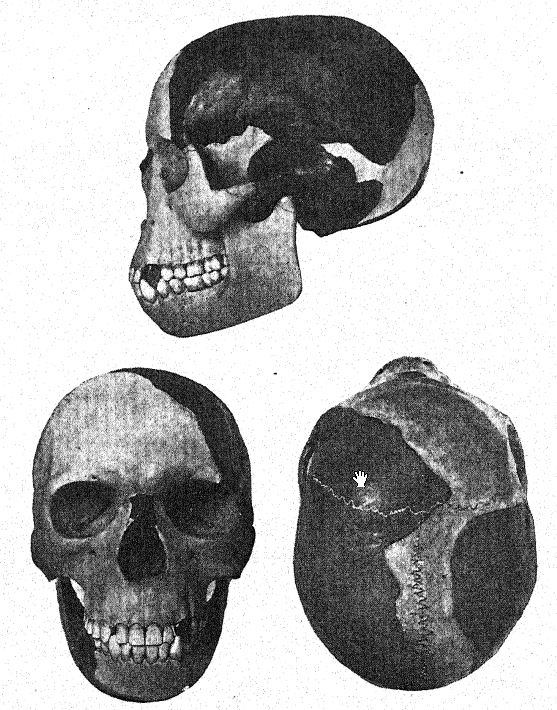

The ‘dawn man’ is the most ancient human type in which the form of the head and size of the brain are known. Its anatomy, as well as its geologic antiquity, is therefore of profound interest and worthy of very full consideration. We may first review the authors’ narrative of this remarkable discovery and the history of opinion concerning it.

Piltdown, Sussex, lies between two branches of the Ouse, about 35 miles south and slightly to the east of Gray’s Thurrock, the Chellean station of the Thames. To the east is the plateau of Kent, in which many flints of Eolithic type have been found.

[ p. 131 ]

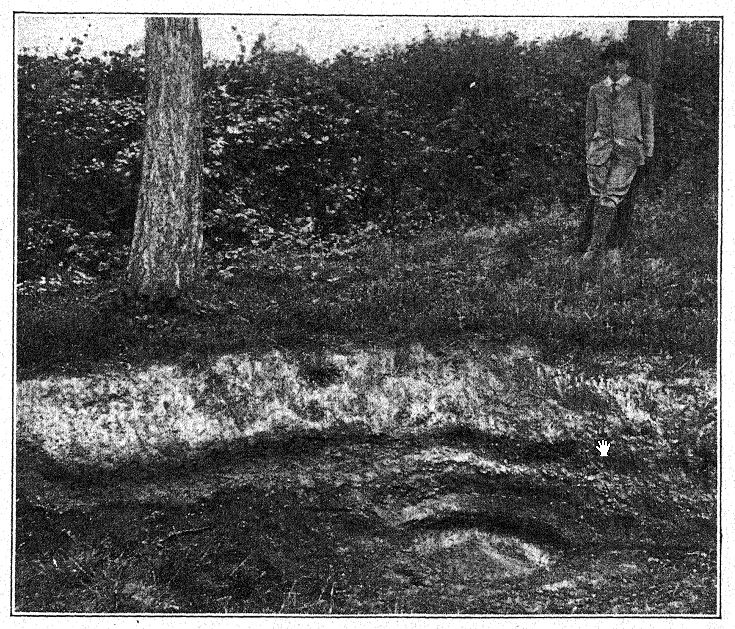

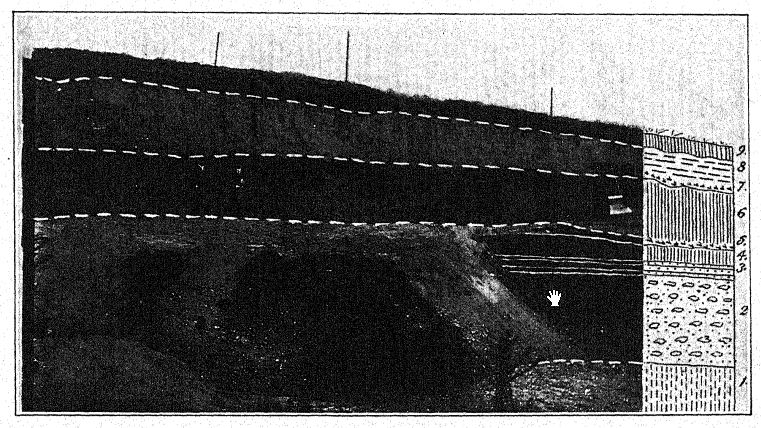

The gravel layer in which the Piltdown skull occurred is situated on a well-defined plateau of large area and lies about 80 feet above the level of the main stream of the Ouse. Remnants of the flint-bearing gravels and drifts occur upon the plateau and the slopes down which they trail toward the river and streams. This region was undoubtedly favorable to the flint workers of Pre-Chellean and Chellean times. Kennard16 believes that the gravels are of the same age as those of the ‘high terrace’ of the lower valley of the Thames ; the height above the stream level is practically the same, namely, about 80 feet. Another geologist, Clement Reid,17 holds that the plateau, composed of Wealden chalk, through which flowed the stream bearing the Piltdown gravels, belongs to a period later than that of the maximum depression [ p. 132 ] . of Great Britain ; that the deposits are of Pre-Glacial or early Pleistocene age; that they belong to the epoch after the cold period of the first glaciation had passed but occur at the very base of the succession of implement-bearing deposits in the southeast of England.

On the other hand, Dawson,18 the discoverer of the Piltdown skull, in his first description states : “From these facts it appears probable that the skull and mandible cannot safely be described as being of earlier date than the first half of the Pleistocene Epoch. The individual probably lived during the warm cycle in that age.”

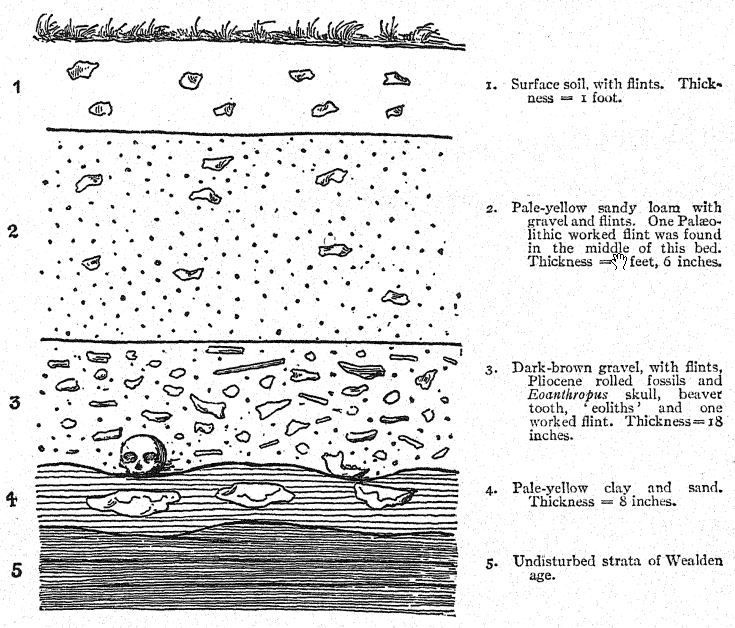

The section of the gravel bed (Fig. 64) indicates that the remains of the Piltdown man were washed dovoi with other fossils by a shallow stream charged with dark-brown gravel and unworked flints; some of these fossils were of Pliocene times from strata of the upper parts of the stream. In this channel were found the remains of a number of animals of the same age as the Piltdown man, a few flints resembling eoliths, and one very primitive worked flint of Pre-Chellean type, which may also have been washed down from deposits of earlier age. These precious geologic and archaeologic records furnish the only means we have of determining the age of Eoanthropus, the ‘dawn man,’ one of the most important and significant discoveries in the whole history of anthropology. We are indebted to the geologist Charles Dawson and the palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward for preser’ving these ancient records and describing them with great fulness and accuracy as follows (pp. 132 to 139) :

Several years ago Dawson discovered a small portion of an unusually thick human parietal bone, taken from a gravel bed which was being dug for road-making purposes on a farm close to Piltdown Common. In the autumn of 1911 he picked up among the rain-washed spoil-heaps of the same gravel-pit another and larger piece of bone belonging to the forehead region of the same skull and including a portion of the ridge extending over the left eyebrow. Immediately impressed with the importance of this discovery, Dawson enlisted the co-operation of Smith Woodward, and a systematic search was made in these spoilheaps [ p. 133 ] and gravels, beginning in the spring of igia ; all the material was looked over and carefully sifted. It appears that the whole or greater part of the human skull had been scattered by the workmen, who had thrown away the pieces unnoticed. Thorough search in the bottom of the gravel bed itself revealed the right half of a jaw, which was found in a depression of undisturbed, finely stratified gravel, so far as could be judged on the spot identical with that from which the first portions of the cranium were exhumed. A yard from the jaw an important piece of the occipital bone of the skull was found. Search was renewed in 1913 by Father P. Teilhard, of Chardin, a French anthropologist, who fortunately recovered a single canine tooth, and later a pair of nasal bones were found, all of which fragments [ p. 134 ] are of very great significance in the restoration of the skull.

1. Surface soil, with flints. Thickness = 1 foot.

2. Pale-yellow sandy loam with gravel and flints. One Palaeolithic worked flint was found in the middle of this bed. Thickness = 2 feet, 6 inches.

3. Bark-brown gravel, with flints, Pliocene rolled fossils and Eoanthropus skull, beaver tooth, ‘eoliths’ and one worked flint. Thickness— 18 inches.

4. Pale-yellow clay and sand. Thickness = 8 inches.

5. Undisturbed strata of Wealden age.

The jaw appears to have been broken at the symphysis, and somewhat abraded, perhaps after being caught in the gravel before it was completely covered with sand. The fragments of the cranium show little or no signs of stream rolling or other abrasion save an incision caused by the workman’s pick.

Analysis of the bones showed that the skull was in a condition of fossilization, no gelatine or organic matter remained, and mingled with a large proportion of the phosphates, originally present, was a considerable proportion of iron.[6]

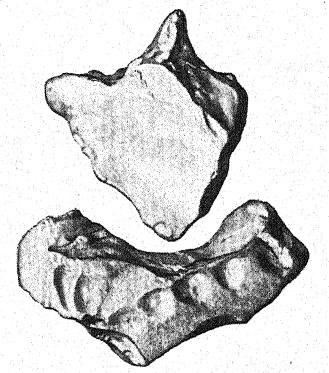

The dark gravel bed (Fig. 64, layer 3), 18 inches in thickness, at the bottom of which the skull and jaw were found, contained a number of fossils which manifestly were not of the same age as the skull but were certainly from Pliocene deposits up-stream; these included the water-vole and remains of the mastodon, the southern mammoth, the hippopotamus, and a fragment of the grinding-tooth of a primitive elephant, resembling Stegodon. In the spoil-heaps, from which it is believed the skull of the Piltdown man was taken, were foxmd an upper tooth of a rhinoceros, either of the Etruscan or of Merck’s type ; the tooth of a beaver and of a hippopotamus, and the leg-bone of a deer, which may have been cut or incised by man. Much more distinctive was a [ p. 135 ] single flint (Fig. 65), worked only on one side, of the very primitive or Pre-Chellean type. Implements of this stage, as the author observes, are difficult to classify with certainty, owing to the rudeness of their workmanship ; they resemble certain rude implements occasionally found on the surface of the chalk downs near Piltdown. The majority of the flints found in the gravel were worked only on one face ; their form is thick, and the flaking is broad and sparing; the original surface of the flint is left in a smooth, natural condition at the point grasped by the hand; the whole implement thus has a very rude and massive form. These flints appear to be of even more primitive form than those at St. Acheul described as Pre-Chellean by Commont.

a. Borer (above).

b. Curved scraper (below).

The eoliths found in the gravelpit and in the adjacent fields are of the ‘borer’ and ‘hollow-scraper’ forms; also, some are of the ‘crescent-shaped-scraper’ type, mostly rolled and water-worn, as if transported from a distance. This is a stream or river bed, not a Palaeolithic quarry.

There can be little doubt, however, that the Piltdown man belonged to a period when the flint industry was in a very primitive stage, antecedent to the true Chellean. It has subsequently been observed that the gravel strata (3) containing the Piltdown man were deeper than the higher stratum containing flints nearer the Chellean type.

The discovery of this skull aroused interest as great as or even greater than that attending the discovery of the two other ‘river-drift’ races, the Trinil and the Heidelberg. In this discussion the most distinguished anatomists of Great Britain, Arthur Smith Woodward, Elliot Smith, and Arthur Keith, took [ p. 136 ] part, and finally the original pieces were re-examined by three anatomists of this country.[7]

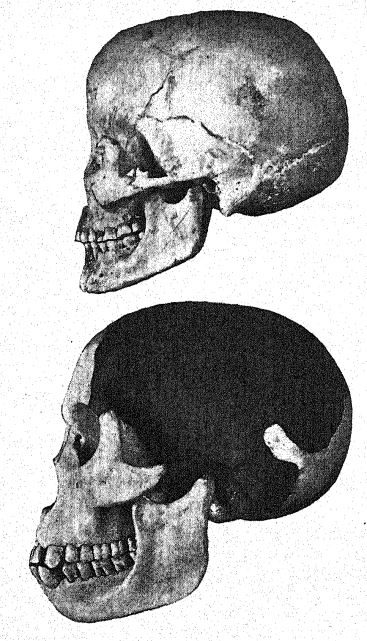

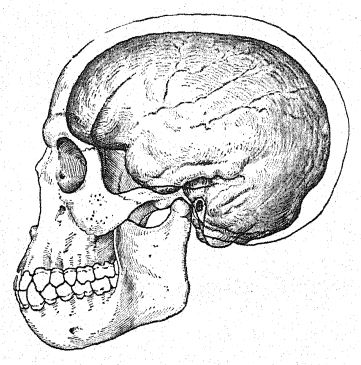

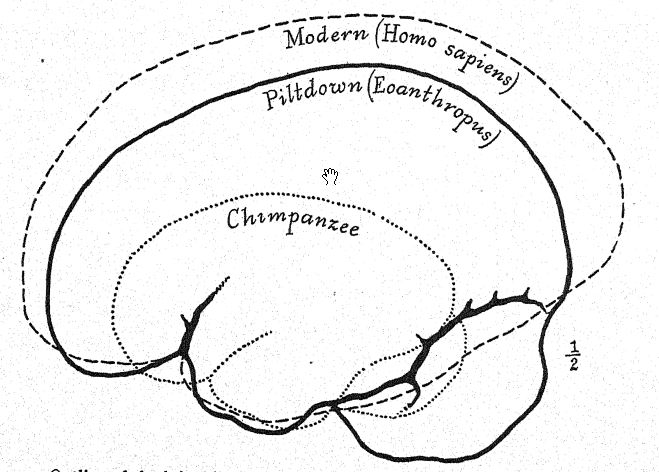

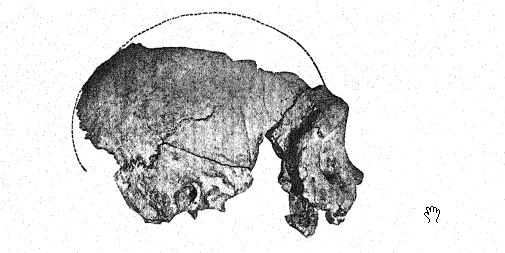

It is important to present in full the original opinions of Smith Woodward, who devoted most careful study to the first reconstruction of the skull (Fig. 67), a model which was subsequently modified by the actual discovery of one of the canine teeth. In his original description it is observed that the pieces of the skull preserved are noteworthy for the great thickness of the bone, it being 11 to 12 mm. as compared with 5 to 6 mm., the average thickness in the modem European skull, or 6 to 8 mm., the thickness in the skull of the Neanderthal races and in that of the modem Australian ; the cephalic index is estimated at 78 or 79, that is, the skull is believed to have been proportionately low and wide, almost brachycephalic ; there was apparently no prominent or thickened ridge above the orbits, a feature which immediately distinguishes this skull from that of the Neanderthal races ; the several bones of the brain-case are typically human and not in the least like those of the anthropoid apes ; the brain capacity was originally estimated at 1070 c. cm., not equalling that of some of the lowest brain types in the existing Australian races and decidedly [ p. 137 ] below that of the Neanderthal man of Spy and La Chapelle-aux-Saints ; the nasal bones are typically human but relatively small and broad, so that the nose was flattened, resembling that in some of the existing Malay and African races.

The jaw presents profoundly different characters; the whole of the bone preserved closely resembles that of a young chimpanzee; thus the slope of the bony chin as restored is between that of an adult ape and that of the Heidelberg man, with an extremely receding chin; the ascending portion of the jaw for the attachment of the temporal muscles is broad and thickened [ p. 138 ] anteriorly. Associated with the jaw were two elongated molar teeth, worn down by use to such an extent that the individual could not have been less than thirty years of age and was probably older. These teeth are relatively longer and narrower than those in the modern human jaw. The canine tooth, identified by Smith Woodward, as belonging in the lower jaw, strengthened by the evidence afforded by the jaw itself, proves that the face was elongate or prognathous and that the canine teeth were very prominent like those of the anthropoid apes; it affords definite proof that the front teeth of the Piltdown man resembled those of the ape.

The author’s conclusion is that while the skull is essentially human, it approaches the lower races of man in certain characters of the brain, in the attachment of the muscles of the neck, in the large extent of the temporal muscles attached to the jaw, and in the probably large size of the face. The mandible, on the other hand, appears precisely like that of the ape, with nothing human except the molar teeth, and even these approach the dentition of the apes in their elongate shape and welldeveloped fifth or posterior intermediate cusp. This type of man, distinguished by the smooth forehead and supraorbital borders and ape-like jaw, represents a new genus called Eoanthropus, or ‘dawn man,’ while the species has been named dawsowi in honor of the discoverer, Charles Dawson. This very ancient type of man is defined by the ape-like chin and junction of the two halves of the jaw, by a series of parallel grinding-teeth, with narrow lower molar teeth, which do not diminish in size backward, and by the steep forehead and sKght development of the brow ridges. The jaw manifestly differs from that of the Heidelberg man in its comparative slenderness and relative deepening toward the symphysis.

The discussion of this very important paper by Smith Woodward and Dawson centred about two points. First, whether the ape-like jaw really belonged with the human skull rather than with that of some anthropoid ape which happened to be drifted down in the same stratum ; and second, whether the extremely [ p. 139 ] iow original estimate of the brain capacity of 1070 c. cm., was not due to incorrect adjustment or reconstruction of the separate pieces of the skull.

Keith,19 the leader in the criticism of Woodward’s reconstruction, maintained that when the two sides of the skull were properly restored and made approximately symmetrical, the brain capacity would be found to equal 1500 c. cm. ; the brain cast of the skull even as originally reconstructed was found to be close to 1 200 c. cm. This author agreed that skull, jaw, and canine tooth belonged to Eoanthropus but that they could not well belong to the same individual.

In defense of Woodward’s reconstruction came the powerful support of Elliot Smith.20 He maintained that the evidence afforded by the re-examination of the bones corroborated in the main Smith Woodward’s identification of the median plane of the skull; further, that the original reconstruction of the prognathous face was confirmed by the discovery of the canine tooth, also that there remained no doubt that the association of the skull, the jaw, and the canine tooth was a correct one. The back portion of the skull is decidedly asymmetrical, a condition found both in the lower and higher races of man. A slight rearrangement and widening of the bones along the median upper line of the skull raise the estimate of the brain capacity to 1100 c. cm. as the probable maximum.

Elliot Smith continued that he considered the brain to be of a more primitive kind than any human brain that he had ever seen, yet that it could be called human and that it already showed a considerable development of those parts which in modern man we associate with the power of speech ; thus, there was no doubt of the unique importance of this skull as representing an entirely new type of “man in the making.” As regards the form of the lower jaw, it was observed that in the dawn of human existence teeth suitable for weapons of offense and defense were retained long after the brain had attained its human status. Thus the ape-like form of the chin does not signify inability to speak, for speech must have come when the jaws were still ape-like in character, [ p. 140 ] and the bony changes that produced the recession of the tooth line and the form of the chin were mainly due to sexual selection, to the reduction in the size of the grinding-teeth, and, in a minor degree, to the growth and specialization of the muscles of the jaw and tongue employed in speech.

At first sight the brain-case resembles that of the Neanderthal skull found at Gibraltar, which is supposed to be that of a woman; it is relatively long, narrow, and especially flat, but it is smaller and presents more primitive features than those of any known human brain. Taking all these features into consideration, we must regard this as being the most primitive and most ape-like human brain so far [ p. 141 ] recorded ; one such as might reasonably be associated with a jaw which presented such distinctive ape characters. The brain, however, is far more human than the jaw, from which we may infer that the evolution of the brain preceded that of the mandible, as well as the development of beauty of the face and the human development of the bodily characters in general.

The latest opinion of Smith Woodward[8] is that the brain, while the most primitive which has been discovered, had a bulk of nearly 1300 c. cm., equalling that of the smaller human brains of to-day and surpassing that of the Austrahans, which rarely exceeds 1250 c. cm.

The original views of Smith Woodward and of Elliot Smith regarding the relation of the Piltdown race to the Heidelberg and Neanderthal races are also of very great interest and may be cited. First, the fact that the Piltdown and Heidelberg races are almost of the same geologic age proves that at the end of the Pliocene Epoch the representatives of man in western Europe had. already branched into widely divergent groups: the one (Heidelberg-Neanderthal) characterized by a very low projecting forehead, with a subhuman head of Neanderthaloid contour ; the other with a flattened forehead and with an ape-like jaw of the Piltdown contour. We should not forget that in the Piltdown skull the absence of prominent ridges above the eyes may possibly be due in some degree to the fact that the type skull may belong to a female, as suggested by certain characters of the jaw ; but among all existing apes the skull in early life has the rounded shape of the Piltdown skull, with a high forehead and ‘scarcely any brow ridges. It seems reasonable, therefore, to interpret the Piltdown skull as exhibiting a closer resemblance to the skulls of our human ancestors in mid-Tertiary times than any fossil skull hitherto found. If this view be accepted, we may suppose that the Piltdown type became gradually modified into the Neanderthal type by a series of changes similar to those passed through by the early apes as they evolved into typical modern apes, with their low brows and prominent ridges above the eyes. This [ p. 142 ] would tend to support the theory that the Neanderthal men were degenerate offshoots of the Tertiary race, of which the Piltdown skull provides the first discovered evidence—a race with a simple, flattened forehead and developed eye ridges.

Elliot Smith concluded that members of the Piltdown race might well have been the direct ancestors of the existing species of man (Homo Sapiens), thus affording a direct link with undiscovered Tertiary apes; whereas, the more recent fossil men of the Neanderthal type, with prominent brow ridges resembling those of the existing apes, may have belonged to a degenerate race which later became extinct. According to this view, Eoanthropus represents a persistent and very slightly modified descendant of the type of Tertiary man which was the common [ p. 143 ] ancestor of a branch giving rise to Homo sapiens, on the one hand, and of another branch giving rise to Homo neanderthalensis, on the other.

Another theory as to the relationships of Eoanthropus is that of Marcelin Boule,21 who is inclined to regard the jaws of the Piltdown and Heidelberg races as of similar geologic age, but of dissimilar racial type. He continues : “If the skull and jaw of Piltdown belong to the same individual, and if the mandibles of the Heidelberg and Piltdown men are of the same type, this discovery is most valuable in establishing the cranial structure of the Heidelberg race. But it appears rather that we have here two types of man which lied in Chellean times, both distinguished by very low cranial characters. Of these the Piltdown race seems [ p. 144 ] to us the probable ancestor in the direct line of the retent species of man, Homo sapiens ; while the Heidelberg race may be considered, until we have further knowledge, as a possible precursor of Homo neanderthalensis.”

The latest opinion of the German anatomist Schwalbe22 is that the proper restoration of the region of the chin in the Piltdown man might make it possible to refer this jaw to Homo sapiens, but this would merely prove that Homo sapiens already existed in early Pleistocene times. The skull of the Piltdown man, continues Schwalbe, corresponds with that of a well-developed, good-sized skull of Homo sapiens ; the only unusual feature is the remarkable thickness of the bone.[9]

Finally, our own opinion is that the Piltdown race is not ancestral to either the Heidelbergs or the Neanderthals. Very recently[10] the jaw of the Piltdown man has been restudied and referred by more than one expert to a fully adult chimpanzee. This leaves us still in doubt as to the exact geologic age and relationships of the Piltdown man (see Appendix, Note IX), whom we are still inclined to regard as a side branch of the human family as shown in the family tree on p. 491.

¶ Mammalian Life of Chellean and Acheulean Times23

The mammalian life which we find with the more advanced implements of Chellean times apparently does not include the old Pliocene mammals, such as the, Etruscan rhinoceros and the sabre-tooth tiger. With this exception it is so simhar to that of Second Interglacial times that it may serve to prove again that the third glaciation was a local episode and not a wide-spread climatic influence. This life is everywhere the same, from the [ p. 145 ] [ p. 146 ] [ p. 147 ] valley of the Thames, as witnessed in the low river-gravels of Gray’s Thurrock and Ilford, to the region of the present Thu ringian forests near Weimar, where it is found in the deposits of Tauhach, Ehringsdorf, and Achenheim, in which the mammals belong to the more recent date of early Acheulean culture. The life of this great region during Chellean and early Acheulean times was amingling of the characteristic forest and meadow fauna of western Europe with the descendants of the African-Asiatic invaders of late Pliocene and early Pleistocene times.

The forests were full of the red deer (Cervus elaphus), of the roe-deer (C. capreolus), and of the giant deer (Megaceros), also of a primitive species of wild boar (Sus scrofa ferus) and of wild horses probably representing more than one variety. The brown bear (Ursus arctos) of Europe is now for the first time identified j there was also a primitive species of wolf (Canis suessi) .

The small carnivora of the forests and of the streams are all considered as closely related to existing species, namely, the badger (Meles taxus), the marten (Mustela martes), the otter (Lutra vulgaris), and the water-vole (Arvicola amphihius). The prehistoric beaver of Europe (Castor fiber) now replaces the giant beaver (Trogontherium) of Second Interglacial times.

- Southern mammoth.

- Hippopotamus.

- Straight-tusked elephant.

- Broad-nosed rhinoceros.

- Spotted hyaena.

- Lion.

- Bison and wild ox.

- Red deer.

- Roe-deer.

- Giant deer.

- Brown bear.

- Wolf.

- Badger.

- Marten.

- Otter.

- Beaver.

- Hamster.

- Water-vole.

Among the large carnivora, the lion (Felis leo antiqua) and the spotted hysna (H. crocuta) have replaced the sabre-tooth tiger and the striped hyaena of early Pleistocene times. Four great Asiatic mammals, including two species of elephants, one species of rhinoceros, and the hippopotamus, roamed through the forests and meadows of this warm temperate region. The horse of this period is considered^^ to belong to the Forest or Nordic type, from which our modem draught-horses have descended. The [ p. 148 ] lions and hysenas which abounded in Chellean and early Acheulean times are in part ancestors of the cave types which appear in the succeeding Reindeer or Cavern Period. In general, this mammalian life of Chellean and early Acheulean times in Europe frequented the river shores and the neighboring forests and meadows favored by a warm temperate climate with mild winters, such as is indicated by the presence of the fig-tree and of the Canary laurel in the region of north central France near Paris.

Undoubtedly the Chellean and Acheulean hunters had begun the chase both of the bison, or wisent (B. priscus), and of the wild cattle, or aurochs.[11]

This warm temperate mammallan life spread very widely over northern Europe, as shown especially in the distribution (Fig. 44) of the hippopotamus, the straight-tusked elephant, and Merck’s rhinoceros. The latter pair were constant companions and are seen to have a closely similar and somewhat more northerly range than the hippopotamus, which is rather the climatic companion of the southern mammoth and ranges farther south. These animals in the gravel and sand layers along the river slopes and ‘terraces’ mingled their remains with the artifacts of the flint workers. For example, in the gravel ‘terraces’ of the Somme we find the bones of the straight-tusked elephant and Merck’s rhinoceros in the same sand layers with the Chellean flints. Thus the men of Chellean times may well have pursued this giant elephant (E. antjquus) and rhinoceros (D. merckii) as their tribal successors in the same valley hunted the woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros.

¶ Distribution or the Chellean Implements

All over the world may be found traces of a Stone Age, ancient or modem, primitive implements of stone and flint analogous to [ p. 149 ] those of the true Chellean period of western Europe but not really identical when very closely compared. These represent the early attempts of the human hand, directed by the primitive mind, to faslhon hard materials into forms adapted to the purposes of war, the chase, and domestic life. The result is a series of parallels in form which come under the evolution principle of convergence. Thus, in all the continents except Australia — in Europe, in Asia, and even in North and South America —primitive races have passed through an industrial stage similar to the typical Chellean of w^estem Europe. This we should rather attribute to a similarity in human invention and in human needs than to the theory that the Chellean industry originated at some particular centre and travelled in a slowly enlarging wave over the entire world.

[ p. 150 ]

In western Europe the Chellean culture certainly had a development all its own, adapted to a race of bold hunters who lived in the open and whose entire industry developed around the products of the chase. For them flint and quartzite took the place of bronze, iron, or steel. This culture marked a distinct and probably a very long epoch of time in which inventions and multiplications of form were gradually spread from tribe to tribe. exactly as modem inventions, usually originating at a single point and often in the mind of one ingenious individual, gradually spread over the world.

The clearest examples of the evolution of the seven or eight implements of the Chellean culture from the five or six rudimentary types of the Pre-Chellean have been found at St. Acheul by Commont. The abundance and variety of flin t at this great station on the Somme made it a centre of industry from the dawn of the Old Stone Age to its very close. It was probably a region favorable to all kinds of large and small game. The researches of Commont show that with the exception of Castillo in northern Spain no other station in aH Europe was so continuously occupied. [ p. 151 ] From Pre-Chellean to Neolithic times the men of every culture stage except the Magdalenian and Azilian-Tardenoisian found their way here, and thus the site of St. Acheul presents an epitome of the entire prehistoric industry. Even during the colder periods of climate this region continued to be visited —possibly during the warm weather of the summer seasons. At Montieres, along the Somme, we find deposits of Mousterian culture which is generally characteristic of the cold climatic period but is here associated with a temperate fauna, including the hippopotamus, Merck’s rhinoceros, and the straight-tusked elephant. Great geographic and climatic changes took place in the valley of the Somme during this long period of human evolution. The Pre-Chellean workers first established their industry on the middle and high ‘terraces’ at the time when the Somme was visited by the straight-tusked elephant and other much more primitive mammals of the warm Asiatic fauna. The early Acheulean camps on the same terraces were pitched in the gravels below layers of ‘loess’ which betoken an entire climatic change. The fourth glaciation passed by, and the Upper Palaeolithic flint [ p. 152 ] workers again returned and left the debris of their industry in the layers of loam which swept down the slopes of the valley from the surrounding hills. This succession wiU be studied more in detail in connection with the industry.

As contrasted with the four or more Pre-Chellean stations already known, namely, St. xAcheul, Montieres, Helin, Gray’s Thurrock, and possibly Abbeville and Piltdown, there are at least sixteen stations in western Europe which are characteristically Chellean. In addition to the sites named above, all of which show deposits of typical Chellean implements above the Pre-Chellean, we may note the important Chellean stations of San Isidro and Torralba in central Spain ; Tilloux and Marignac in southwestern France; Creteil, Colombes, Bois Colombes, and Billancourt on the Seine, in the immediate vicinity of Paris; Cergy on the Oise; the type station of Chelles on the Marne; Abbeville on the northern bank of the Somme ; and the famous station of Kent’s Hole, Devon, on the southwestern coast of England. Thus far no typical Chellean station has been discovered in Portugal, Italy, Germany, or Austria, nor, indeed, in any part of central Europe. This leaves the original habitat of the tribes that brought the Chellean culture to western Europe still a mystery ; but, as already observed, the location of the stations favors the theory of a migration through northern Africa rather than through eastern Europe.

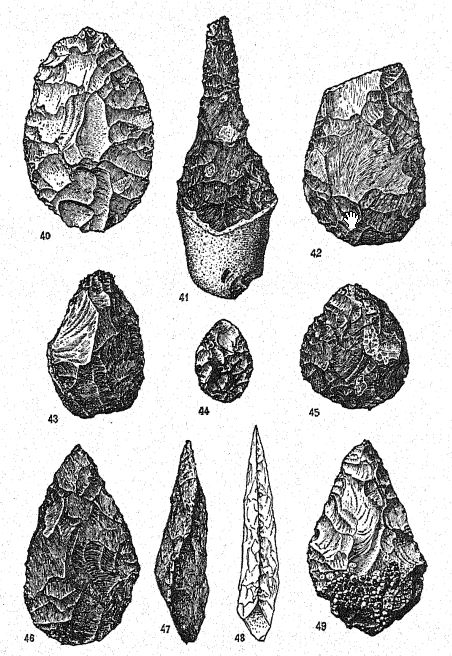

Compared with the Pre-Chellean flint workers the Chellean artisans advanced both by the improvement of the older types of implements and by the invention of new ones.25 As observed by Obermaier, the flint worker is still dependent on the chance shape of the shattered fragments of flint which he has not yet learned to shape symmetrically. In the experimental search after the most useful form of flint which could be grasped by the hand, the very characteristic Chellean coup de poing was evolved out of its Pre-Chellean prototype. This implement was made of an elongate nodule, either of quartzite or, preferably, of flint, and flaked by the hammer on both sides to a more or less almond shape ; as a rule, the point and its adjacent edges are sharpened ; the [ p. 153 ] [ p. 154 ] other end being rounded and blunted. Like most, if not all, of the Chellean implements, it was designed to be grasped by the bare hand and not furnished with a wooden haft or handle. It is not impossible that some of the pointed forms may have been wedged into a wooden handle, but there is no proof of it. In size the coup de poing varies from 4 to 8 inches in length, and examples have been found as large as 9½ inches. That it served a variety of purposes is indicated by the existence of four welldefined, different forms : first, a primitive, almond-shaped form ; second, an ovaloid form; third, a disk form; and fourth, a pointed form resembling a lance-head. De Mortilleff26 speaks of it as the only tool of the Chellean tribes, but in its various forms it served all the purposes of axe, saw, chisel, and awl, and was in truth a combination tool, Capitan27 also holds that the coup de poing is not a single tool but is designed to meet many various needs. The primitive almond and ovaloid forms were designed for use along the edges, either for heavy hacking or for sawing ; the disk forms may have been used as axes or as sling-stones ; the more rounded forms would serve as knives and scrapers; while the pointed, lance-shaped forms might be used as daggers, both in war and in the chase.

The Chellean flint workers also developed especially a number of small, pointed forms from the accidentally shaped fragments of flint, showing both short and long points carefully flaked and chipped. Thus, out of the small types of the Pre-Chellean there evolved a great variety of tools adapted to domestic purposes, to war, and to the chase.

¶ Chellean Geography in England and France

The t5^e station of the Chellean culture is somewhat east of the present town of CheUes. Here in Chellean times the broad floods of the ancient River Marne were transporting great quantities of sand and debris, products of the early pluvial periods of Third Interglacial times; and here, on the right bank, embedded in sands and gravels 24 feet thick, are found the typical Chellean [ p. 155 ] implements mingled with, remains of the hippopotamus, straight-tusked elephant, Merck’s rhinoceros, giant beaver, hyaena, and many members of the Asiatic forest and meadow fauna.

The flint-working stations at St. Acheul were on bluffs from 40 to 80 feet above the present level of the Somme. The Chellean and the following Acheulean industry was carried on here on a very extensive scale. In one year Rigollot collected as many as 800 coups de poing from the ancient quarries; near by are other quarries equally rich in material, and we may imagine that the products of the flint industry in this favorable locality were carried far and wide into other parts of the country.

In the vicinity of Paris, and again at Arcy, in the valley of the BiSvre, the workers of Chellean, Acheulean, and Mousterian flints sought in succession the old river-gravels belonging to the lower levels; these ‘low terraces’ are only 15 feet above the present height of the river and are still occasionally flooded by the high waters of the Seine, indicating that the Seine borders have not altered their levels. The animal life here was identical with that of the Somme and of the Thames and included the hippopotamus, Merck’s rhinoceros, and the straight-tusked elephant.

Thus it would appear that, in regard to the river courses and the hills through which they flowed, the topography and landscape of northern France and of southern Britain were everywhere the same as at the present time. The forests which clothed the hills were not greatly different from the present, except for the presence of a few trees of a warmer clime, nor was there anything strange or unfamiliar in the majority of the animals that roamed through forest and meadow. The three chief archaic elements consisted in the presence of two very ancient races of men and their rude stage of culture, in the great forms of Asiatic and African life which mingled with the more famihar native types, and in the broad, continuous land surfaces which swept off unbroken to the west and southwest.

For in those days Europe, though even then little more than a great peninsula, extended far beyond its present limits. England and Ireland were still part of the mainland, and great rivers [ p. 156 ] flowed through the broad valleys that are now the Irish Sea, the North Sea, and the English Channel — rivers that counted the Seine, the Thames, the Garonne, and even the Rhine, as mere tributaries. The Strait of Gibraltar was then the Isthmus of Gibraltar — a narrow land bridge connecting Europe with .Africa. The Mediterranean was then an inland lake, or rather two inland lakes, for Italy and Sicily stretched out in a broad, irregular mass to join the northern coast of Africa, while Corsica and Sardinia formed a long peninsula extending from the Italian mainland and almost, if not quite, reaching to the African coast.

¶ The Thames Valley in Chellean Times

The interpretation of the features of stratification in the valley of the Somme is especially interesting because it gives us a key to the understanding of a similar sequence of prehistoric events in the valley of the Thames.

The station of Gray’s Thurrock in this valley is barely 120 miles distant from the Chellean station of Abbeville, in the valley of the Somme, and it is apparent that the old flint workers were freely passing across the broad intervening country and interchanging their ideas and inventions. Thus it happened that Chellean implements identical with, or closely related to, the types of the Somme valley were being fashioned all over southern Britain from the Thames to the Ouse. The ancient River Thames (Lyell,28 Geikie29) was then flowing over a bed of boulder-clays which had been deposited during the preceding glaciations. Its broad, swift stream was bringing down great deposits of ochreous gravels and of sands interstratified with loams and clays. It is these old true river-gravels which display their greatest thickness on the lowest levels of the Thames and which are largely made up of well-bedded and distinctly water-worn materials. On these low levels the flint workers sought their materials, and here they left behind them the archaic Chellean implements which are now found embedded in these older river-gravels, just as they occur in the gravels washed down over the three terraces of the Somme and the Marne. In the Thames this old gravel wash seems to have [ p. 157 ] been down-stream, whereas on the middle and upper terraces of the Somme the gravel wash came directly down the sides of the valley, except, perhaps, in very high floods. These deep beds of gravel, sand, and loam lie for the most part above the present overflow plain of the Thames, although in some places they descend below it ; which proves that the main landscape of the Thames also, except for the changes of the flora and of animal life, was the same in Pre-Chellean and Chellean times as it is at present. Thus the Somme, the Thames, and the Seine had all worn their channels to the present or even to lower levels when the Pre-Chellean hunters appeared. Since Chellean times all three rivers have silted up their channels.

The changes along the Thames which have since occurred are in the superficial layers brought down from the sides of the valley which have softened the contours of the old terraces and have also entombed the later phases of the valley’s prehistory.

Sections on the south bank at Ilford, Kent, and on the north bank at Gray’s Thurrock, Essex, confirm this view. At the latter station, in low-l3dng strata of brick-earth, loam, and gravel, such as would be formed by the silting up of the bottom of an old river channel, are found the remains of the straight-tusked elephant, broad-nosed rhinoceros, and hippopotamus. All the discoveries of recent years lead to the conclusion that the old fluviatile gravels which contain these ancient mammals and flints are restricted to the lower levels of the Thames valley, while the high level gravels and loams are of later date. Old Chellean flints also occur occasionally on the higher levels, but here it would seem that they have been washed down from the old land surfaces above, because they are found mingled with flints of the late Acheulean and early Mousterian industry.

¶ England in Early Paleolithic Times

It is on the higher levels of the Thames, as of the Somme, and in the superficial deposits covering the sides of the valley that we read the story of the subsequent Palaeolithic cultures and of an early warm temperate climate being followed by a cold climate [ p. 158 ] with frozen subsoil belonging to the fourth glaciation and the contemporary Mousterian flint industry. The Paleolithic history of the Thames30 has not yet been fully interpreted, but it would appear that the relics of the old stations of Kent and Norfolk will yield all the forms of Chellean and Acheulean implements, and probably also those of the Mousterian which have been discovered in the valley of the Somme, thus proving that the Lower Paleeolithic races of this region pursued the same culture development as the neighboring tribes of France and Belgium, as well as those of Spain, up to the close of middle Acheulean times.

A similar sequence of events appears to be indicated at Hoxne, Suffolk, where archaic palaeoliths were discovered as far back as 1797. This discovery was neglected for upward of sixty years, until in 1859 these flints were re-examined by Prestwich and Evans after their visit to the stations of the Somme (Geikie,31 Avebury32). This site was in the hollow of a surface of boulderclay, overlain by the deposit of a fresh-water stream ; in the bed of its narrow channel, besides flint implements of early Acheulean type, abundant plant remains were found which give us an interesting vision of the flora of the time.

These plants are decidedly characteristic of a temperate climate, including such trees as the oak, yew, and fir, and mostly of species w^hich are still found in the forests of the same region. This life gave place, as indicated in plant deposits of a higher level, to an arctic flora, probably corresponding with the tundra climate of Mousterian times, the period of the fourth glaciation. Above these are found again layers of plants and of mollusks which point to the return of a temperate climate.

¶ Spread of the Acheulean Industry

It is noteworthy that not a single ‘river-drift,’ Pre-Chellean or Chellean, station has been found in Germany or Switzerland, or, in fact, in all central Europe in the region lying between the Alpine and Scandinavian glaciers. Either this region was unfavorable [ p. 159 ] to liuman habitation or the remains of the stations have been buried or washed away.

It is significant that the earliest proof of human migration into this region, whether from the east or from the west we do not eertainly know, is coincident with the dry climate of Acheulean times. The ‘loess’ conditions of cHmate seem to be coincident with the earliest Acheulean stations in Germany, such as Sablon. ‘Loess’ deposition is by no means a proof of a cold climate but rather of an arid one, especially in regions where areas of finely eroded soil were liable to be raised by the wind ; such areas were found over the whole recently glaciated country north of the Alps and south of the Scandinavian peninsula.

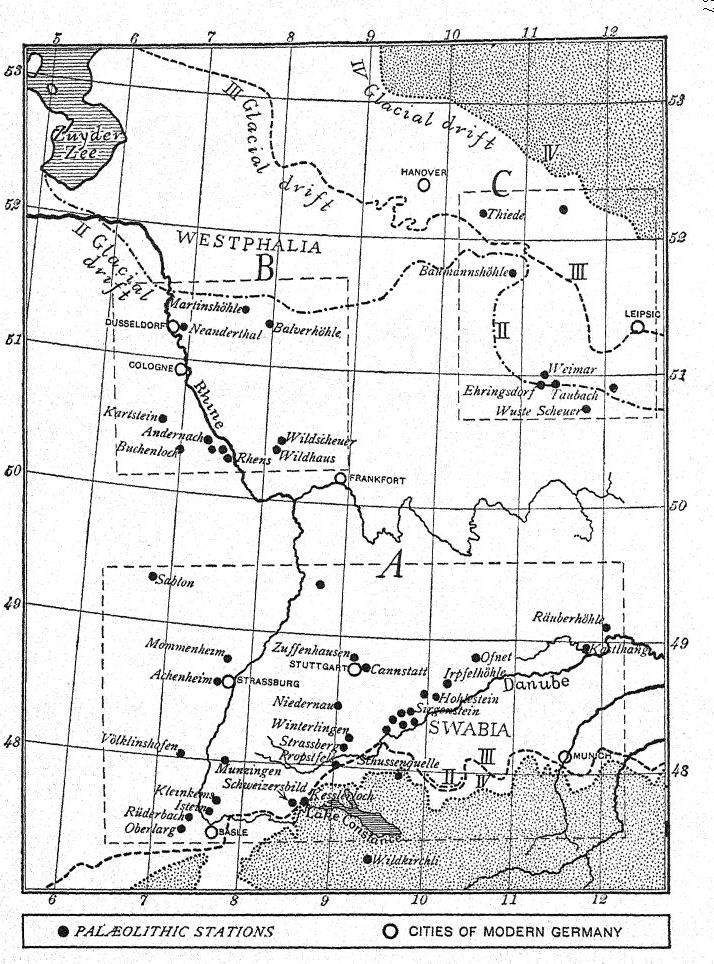

The Palaeolithic discovery sites of Germany are principally grouped in three regions33 as follows :

To the south, along the headwaters of the Rhine and the Danube, among the Umestones of Swabia and the Jura were formed the caverns sought by early Mousterian man. To the west of these were many older stations in the ‘loess’ deposits of the upper Rhine, between the mountain ridges of the Vosges and the Black Forest, and still nearer the sources of the Rhine, extending over the border into Switzerland, are a number of famous cave sites in the valleys cut by the Rhine and its tributaries through the white Jurassic limestone. To the west is the group of the middle Rhine and of Westphalia, which includes the open Acheulean camps in the ‘loess’ deposits above the river and a number of cavern stations. To the north is the scattered group of stations, both of Acheulean and Mousterian times, of north Germany. Here the sites are few and far between. The opencountry camps were estabhshed chiefly in the valley of the Ilm and near the caves of the Harz Mountains, in the neighborhood of Gera. No discoveries of certain date or unquestioned authenticity are reported from eastern Gerwawy.

Along the upper Rhine the flint workers of Acheulean times established their ancient camps mostly in the open on the broad sheets of the ‘lower loess,’ which, constantly drifted by the wind, covered and preserved the stations. These stations are [ p. 160 ] [ p. 161 ] widely scattered, but they were frequented from earliest Acheulean times, and the region was revisited to the very close of the Upper Palaeolithic.