[ p. 1 ]

GREEK CONCEPTIONS OF MAN’S ORIGIN — RISE OF ANTHROPOLOGY, OF ARCHAEOLOGY, OF THE GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF MAN — TIME DIVISIONS OF THE GLACIAL EPOCH — GEOGRAPHIC, CLIMATIC, AND LIFE PERIODS OF THE OLD STONE AGE

The anticipation of nature by Lucretius[1] in his philosophical poem, De Rerum Natura accords in a broad and remarkable way with our present knowledge of the prehistory of man:

“Things throughout proceed

In firm, undevious order, and maintain,

To nature true, their fixt generic stamp.

Yet man’s first sons, as o’er the fields they trod,

Reared from the hardy earth, were hardier far;

Strong built with ampler bones, with muscles nerved

Broad and substantial; to the power of heat.

Of cold, of varying viands, and disease,

Each hour superior; the wild lives of beasts

Leading, while many a lustre o’er them rolled.

Nor crooked plough-share knew they, nor to drive,

Deep through the soil, the rich-returning spade;

Nor how the tender seedling to re-plant,

Nor from the fruit-tree prune the withered branch.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Nor knew they yet the crackling blaze t’excite,

Or clothe their limbs with furs, or savage hides.

But groves concealed them, woods, and hollow hills;

And, when rude rains, or bitter blasts o’erpowered,

Low bushy shrubs their squalid members wrapped.

[ p. 2 ]

“And in tEeir keen rapidity of hand

And foot confiding, oft the savage train

With missile stones they hunted, or the force

Of clubs enormous; many a tribe they felled,

Yet some in caves shunned, cautious; where, at nighty,

Thronged they, like bristly swine; their naked limbs

With herbs and leaves entwining. Nought of fear

Urged them to quit the darkness, and recall,

With clamorous cries, the sunshine and the day:

But sound they sunk in deep, oblivious sleep,

Till o’er the mountains blushed the roseate dawn.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“This ne’er distressed them, but the fear alone

Some ruthless monster might their dreams molest,

The foamy boar, or lion, from their caves

Drive them aghast beneath the midnight shade,

And seize their leaf-wrought couches for themselves.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Yet then scarce more of mortal race than now

Left the sweet lustre of the liquid day.

Some doubtless, oft the prowling monsters gaunt

Grasped in their jaws, abrupt; whence, through the groves.

The woods, the mountains, they vociferous groaned,

Destined thus living to a living tomb.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Yet when, at length, rude huts they first devised,

And fires, and garments; and, in union sweet,

Man wedded woman, the pure joys indulged

Of chaste connubial love, and children rose,

The rough barbarians softened. The warm hearth

Their frames so melted they no more could bear,

As erst, th’ uncovered skies; the nuptial bed

Broke their wild vigor, and the fond caress

Of prattling children from the bosom chased

Their stern ferocious manners.” [2]

This is a picture of many phases in the life of primitive man; his powerful frame, his ignorance of agriculture, his dependence on the fruits and animal products of the earth, his discovery of fire and of clothing, his chase of wild beasts with clubs and missile stones, his repair to caverns, his contests with the lion [ p. 3 ] and the boar, his invention of rude huts and dwellings, the softening of his nature through the sweet influence of family life and of children, all these are veritable stages in our prehistoric development. The influence of Greek thought is also reflected in the Satires of Horace,[3] and the Greek conception of the natural history of man, voiced by AEchylus[4] as early as the fifth century B. C., prevailed widely before the Christian era, when it gradually gave way to the Mosaic conception of special creation, which spread all over western Europe.

¶ Rise of Modern Anthropology

As the idea of the natural history of man again arose, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it came not so much from previous sources as from the dawning science of comparative anatomy. From the year 1597, when a Portuguese sailor’s account of an animal resembling the chimpanzee was embodied in Fihppo Pigafetta’s Description of the Kingdom of the Congo, the many points of likeness between the anthropoid apes and man were treated both in satire and caricature and in serious anatomical comparison as evidence of kinship.

The first French evolutionist. Buffon,[5] observed in 1749: “The first truth that makes itself apparent on serious study of nature is one that man may perhaps find humiliating; it is this—that he, too, must take his place in the ranks of animals, being, as he is, an animal in every material point.” Buffon’s convictions were held in check by clerical and official influences, yet from his study of the orang in 1766 we can entertain no doubt of his belief that men and apes are descended from common ancestors.

The second French evolutionist, Lamarck,[6] in 1809 boldly [ p. 4 ] proclaimed the descent of man from the anthropoid apes, pointing out their close anatomical resemblances combined with inferiority both in bodily and mental capacity. In the evolution of man Lamarck perceived the great importance of the erect position, which is only occasionally assumed by the apes; also that children pass gradually from the quadrumanous to the upright position, and thus repeat the history of their ancestors. Man’s origin is traced as follows: A race of quadrumanous apes gradually acquires the upright position in walking, with a corresponding modification of the limbs, and of the relation of the head and face to the back-bone. Such a race, having mastered all the other animals, spreads out over the world. It checks the increase of the races nearest itself and, spreading in all directions, begins to lead a social life, develops the power of speech and the communication of ideas. It develops also new requirements, one after another, which lead to industrial pursuits and to the gradual perfection of its powers. Eventually this pre-eminent race, having acquired absolute supremacy, comes to be widely different from even the most perfect of the lower animals.

The period following the latest publication of Lamarck’s[7]1 remarkable speculations in the year 1822, was distinguished by the earliest discoveries of the industry of the caveman in southern France in 1828, and in Belgium, near Liege, in 1833; discoveries which afforded the first scientific proof of the geologic antiquity of man and laid the foundations of the science of archaeology.

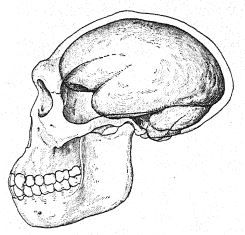

The earliest recognition of an entirely extinct race of men was that which was called the ‘Neanderthal,’ found, in 1856, near Düsseldorf, and immediately recognized by Schaaffhausen2 as a primitive race of low cerebral development and of uncommon bodily strength.

Darwin in the Origin of Species,3 which appeared in 1858, did not discuss the question of human descent, but indicated [ p. 5 ] the belief that light would be thrown by his theory on the origin of man and his history.

It appears that Lamarck’s doctrine in the Philosophic Zoologique(1809)4 made a profound impression on the mind of Lyell, who was the first to treat the descent of man in a broad way from the standpoint of comparative anatomy and of geologic age. In his great work of 1863, The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, Lyell cited Huxley’s estimate of the Neanderthal skull as more primitive than that of the Australian but of surprisingly large cranial capacity. He concludes with the notable statement; “The direct bearing of the ape-like character of the Neanderthal skull on Lamarck’s doctrine of progressive development and transmutation . . . consists in this, that the newly observed deviation from a normal standard of human structure is not in a casual or random direction, but just what might have been anticipated if the laws of variation were such as the transmutationists require. For if we conceive the cranium to be very ancient, it exemplifies a less advanced stage of progressive development and improvement.”5

Lyell followed this by an exhaustive review of all the then, existing evidence in favor of the great geological age of man, considering the ‘river-drift,’ the ‘loess,’ and the loam deposits, and the relations of man to the divisions of the Glacial Epoch. Referring to what is now knovm as the Lower Palaeolithic of St. Acheul and the Upper Palaeolithic of xAurignac, he says that they were doubtless separated by a vast interval of time, when we consider that the flint implements of St. Acheul belong either to the Post-Pliocene or early Pleistocene time, or the ‘older drift.’

It is singular that in the Descent of Man, published in 1871,6 eight years after the appearance of Lyell’ s great work, Charles Darwin made only passing mention of the Neanderthal race, as follows: “Nevertheless, it must he admitted that some skulls of very high antiquity, such as the famous one at Neanderthal, are well-developed and capacious.” It was the relatively large brain capacity which turned Darwin’s attention away from a type [ p. 6 ] which has furnished most powerful support to his theory of human descent. In the two hundred pages which Darwin devotes to the descent of man, he treats especially the evidences presented in comparative anatomy and comparative psychology, as well as the evidence afforded by the comparison of the lower and higher races of man. As regards the “birthplace and antiquity of man,”7 he observes:

“. . . In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is therefore probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee ; and as these two species are now man’s nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere. But it is useless to speculate on this subject ; for two or three anthropomorphous apes, one the Dryopithecus of Lartet, nearly as large as a man, and closely allied to Hylobates, existed in Europe during the Miocene Age ; and since so remote a period the earth has certainly undergone many great revolutions, and there has been ample time for migration on the largest scale.

“At the period and place, whenever and wherever it was, when man first lost his hairy covering, he probably inhabited a hot country; a circumstance favorable for the frugivorous diet on which, judging from analogy, he subsisted. We are far from knowing how long ago it was when man first diverged from the catarrhine stock; but it may have occurred at an epoch as remote as the Eocene Period ; for that the higher apes had diverged from the lower apes as early as the Upper Miocene Period is shown by the existence of the Dryopithecus.”

With this speculation of Darwin the reader should compare the state of our knowledge to-day regarding the descent of man, as presented in the first and last chapters of this volume.

The most telling argument against the Lamarck-Lyell-Darwin theory was the absence of those missing links which, theoretically, should be found connecting man with the anthropoid apes, for at that time the Neanderthal race was not recognized [ p. 7 ] as such. Between 1848 and 19x4 successive discoveries have been made of a series of human fossils belonging to intermediate races: some of these are now recognized as missing links between the existing human species, Homo sapiens, and the anthropoid apes; and others as the earliest known forms of Homo sapiens :

| Year | Locality | Character of Remains | Race |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1848 | Gibraltar. | Well-preserved skull. | Neanderthal. |

| 1856 | Neanderthal, near Düsseldorf. | Skullcap, etc. | Type of Neanderthal race. |

| 1866 | La Naulette, Belgium. | Fragment of lower jaw. | Neanderthal race. |

| 1867 | Furfooz, Belgium. | Two skulls. | Type of Furfooz race. |

| 1868 | Crô-Magnon, Dordogne. | Three skeletons and fragments of two others. | Type of Crô-Magnon race. |

| 1887 | Spy, Belgium. | Two crania and skeletons. | Spy type of Neanderthal race. |

| 1891 | Trinil River, Java. | Skullcap and femur. | Type of Pithecanthropus race. |

| 1899 | Krapina, Austria-Hungary. | Fragments of at least ten individuals. | Krapina type of Neanderthal race. |

| 1901 | Grimaldi grotto, Mentone. | Two skeletons. | Type of Grimaldi race. |

| 1907 | Heidelberg. | Lower jaw with teeth. | Type of Homo heidelbergensis. |

| 1908 | La Chapelle, Corrèze. | Skeleton. | Mousterian type of Neanderthal race. |

| 1908 | Le Moustier, Dordogne. | Almost complete skeleton, greater part of which was in bad state of preservation. | Neanderthal. |

| 1909 | La Ferrassie I, Dordogne. | Fragments of skeleton. | Neanderthal. |

| 1910 | La Ferrassie II, Dordogne. | Fragments of skeleton, female. | Neanderthal. |

| 1911 | La Quina II, Charente. | Fragments of skeleton, supposed female. | Neanderthal. |

| 1911 | Piltdown, Sussex. | Portions of skull and jaw. | Type of Eoanthropus, the ‘dawn man.’ |

| 1914 | Obercassel, near Bonn, Germany. | Two skeletons, male and female. | Crô-Magnon. |

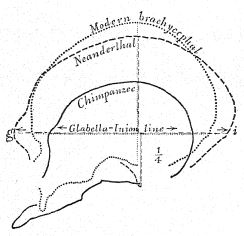

In his classic lecture of 1844., On the Form of the Head in Different Peoples, Anders Retzius laid the foundation of the modern study of the skull.8 Referring to his original pubhcation, he says : “In the system of classification which I devised, I have distinguished just two forms, namely, the short (round or fourcorixered) which I named brachycephalic, and the long, oval, or dolichocephalic. In the former there is little or no difference [ p. 8 ] between the length and breadth of the skull ; in the latter there is a notable difference.” The expression of this primary distinction between races is called the cephalic index, and it is determined as follows:

Breadth of skull x 100 ÷ length of skull.

g. glabella or median prominence between the eyebrows.

i. inion— external occipital protuberance.

g-i. glabella-inion line.

Vertical line from g-i to top of skull indicates the lieight of the brain-case. Modified after Schwalbe.

In this sense the primitive men of the Old Stone Age were mostly ‘dolichocephalic,’ that is, the breadth of the skull was in general less than 75 per cent of the length, as in the existing Australians, Kaffirs, Zulus, Eskimos, and Fijians. But some of the Palaeolithic races were ‘mesaticephalic’; that is, the breadth was between 75 per cent and 80 per cent of the length, as in the existing Chinese and Polynesians. The third or ‘brachycephalic’ type is the exception among Palaeolithic skulls, in which the breadth is over 80 per cent of the length, as in the Malays, Burmese, American Indians, and Andamanese.

The cephalic index, however, teUs us little of the position of the skull as a brain-case in the ascending or descending scale, and following the elaborate systems of skull measurements which were built up by Retzius9 and Broca,10 and based chiefly on the outside characters of the skull, came the modern system of Schwalbe, which has been devised especially to measure the skull with reference to the all-important criterion of the size of the different portions of the brain, and of approximately estimating the cubic capacity of the brain from the more or less complete measurements of the skull.

[ p. 9 ]

Among these measurements are the slope of the forehead, the height of the median portion of the skullcap, and the ratio between the upper portion of the cranial chamber and the lower portion. In brief, the seven principal measures which Schwalbe now employs are chiefly expressions of diameters which correspond with the number of cubic centimetres occupied by the brain as a whole.

In this manner Schwalbe^^ confirms Boule’s estimates of the variations in the cubic capacity of the brain in different members of the Neanderthal race as follows :

Neanderthal race — La Chapelle 1620 c. cm.

“ “ — Neanderthal 1408 “

“ “ — -La Quina 1367 “

“ “ — Gibraltar 1296 “

Thus the variations between the largest known brain in one member of the Neanderthal race, the male skull of La Chapelle, and the smallest brain of the same race, the supposed female skull of Gibraltar, is 324 c. cm., a range similar to that which we find in the existing species of man (Homo sapiens).

As another test for the classification of primitive skulls, we may select the well-known frontal angle of Broca, as modified by Schwalbe, for measuring the retreating forehead. The angle is measured by drawing a line along the forehead upward from the bony ridge between the eyebrows, with a horizontal line carried from the glabella to the inion at the back of the skull. The various primitive races are arranged as follows:

| PERCENT | ||

|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens, with an average forehead | frontal angle | 90 |

| Homo sapiens, with extreme retreating forehead | “ “ | 72.3 |

| Homo neaudcrtlialcnsis, with the least retreating forehead | “ “ | 70 |

| Homo neaudcrthalensis, with the most retreating forehead | “ “ | 57.7 |

| Pithecanthropus crectus (Trinil race) | “ “ | 52.5 |

| Highest anthropoid apes | “ “ | 50 |

[ p. 10 ]

For instance, this illustrates the fact that in the Trinil race the forehead is actually lower than in some of the highest anthropoid apes; that in the Neanderthal race the forehead is more retreating than in any of the existing human races of Homo sapiens.

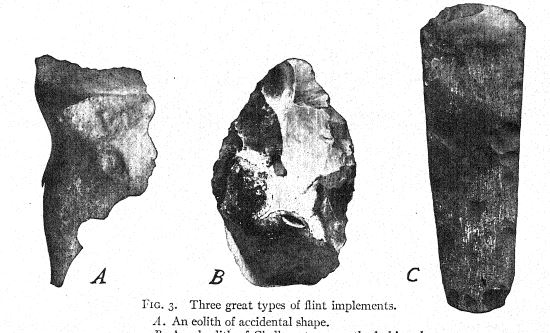

¶ Archaeology of the Old Stone Age

The proofs of the prehistory of man arose afresh, and from an entirely new source, in the beginning of the eighteenth century through discoveries in Germany, by which the Greek anticipations of a stone age were verified. For a century and a half the great animal life of the diluvial world had aroused the wonder and speculation of the early naturalists. In 1750 Eccardus17 of Braunschweig advanced the first steps toward prehistoric chronology in expressing the opinion that the human race first lived in a period in which stone served as the only weapon and tool, and that this was followed by a bronze and then by an iron period of human culture. As early as 1700 a human skull was discovered at Cannstatt and was believed to be of a period as ancient as the mammoth and the cave-bear. [9]

France, favored beyond all other countries by the men of the Old Stone Age, was destined to become the classic centre of prehistoric archeology. As early as 1740 Mahudel18 published a treatise upon stone implements and laid the foundations both of Neolithic and Paleolithic research. By the beginning of the nineteenth century the problem of fossil man had awakened wide-spread interest and research. In Buckland’s19 Reliquiae diluvianae, published in 1824, the great mammals of the Old Stone Age are treated as relics of the flood. In 1825 MacEnery explored the cavern of Kent’s Hole, near Torquay, finding human bones and flint flakes associated with the remains of the [ p. 11 ] cave-bear and cave-hyaena, but the notes of this discovery were not published until 1840, when Godwin-Austen20 gave the first description of Kent’s Hole. In 1828 Tournal and Christol21 announced the first discoveries in France (Languedoc) of the association of human bones with the remains of extinct animals. In 1833-4 Schmerling22 described his explorations in the caverns near Liége, in Belgium, in which he found human bones and rude flint implements intermingled with the remains of the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the cave-hyaena, and the cave-bear. This is the first published evidence of the life of the Cave Period of Europe, and was soon followed by the recognition of similar cavern deposits along the south coast of Great Britain, in France, Belgium and Italy.

The work of the caveman, gradually revealed between 1828 and 1840, is now known to belong to the closing period of the Old Stone Age, and it is very remarkable that the next discovery related to the very dawn of the Old Stone Age, namely, to the life of the 'river-drift’ man of the Lower Palaeolithic.

[ p. 12 ]

This discoverv of what is now known as Chellean and Acheulean industry came through the explorations of Boucher de Perthes, between 1839 and 1846, in the valley of the River Somme, which flows through Amiens and Abbeville and empties into the English Channel half-way between Dieppe and Boulogne. In 1841 this founder of modem archaeology unearthed near Abbeville a single flint, rudely fashioned into a cutting instrument, buried in river sand and associated with mammalian remains. This was followed by the collection of many other ancient weapons and implements, and in the year 1846 Boucher de Perthes published his first work, entitled De l’Industrie primitive, oil des Arts a leur Origine,23 in which he announced that he had found human implements in beds unmistakably belonging to the age of the ‘river-drift.’ This work and the succeeding (1857), Antiquites celtiques et antédiluviennes,24 were received wnth great scepticism until confirmed in 1853 by Rigollot’s25 discovery of the now famous ‘river-drift’ beds of St. Acheul, near Amiens. In the succeeding years the epoch-making work of Boucher de Perthes was welcomed and confirmed by leading British geologists and archreologists. Falconer, Prestwich, Evans, and others who visited the Somme. Lubbock’s26 article of 1862, on the Evidence of the Antiquity of Man Afforded by the Physical Structure of the Somme Valley, pointing out the great geologic age of the river sands and gravels and of the mammals which they contained, was followed by the discovery of similar flints in the ‘river-drifts’ of Suffolk and Kent, England, in the valley of the Thames near Dartford. Thus came the first positive proofs that certain types of stone implements were widespread geographically, and thus was afforded the means of comparing the age of one deposit with another.

This led Sir John Lubbock27 to divide the prehistoric period into four great epochs, in descending order as follows:

The Iron Age, in which iron had superseded bronze for arms, axes, knives, etc., while bronze remained in common use for ornaments.

The Bronze Age, in which bronze was used for arms and cutting instruments of all kinds.

[ p. 13 ]

The later or polished Stone Age, termed by Lubbock the Neolithic Period, characterized by weapons and instruments made of flint and other kinds of stone, with no knowledge of any metal excepting gold.

Age of the Drift, termed by Lubbock the Palaeolithic Period, characterized by chipped or flaked implements of flint and other kinds of stone, and by the presence of the mammoth, the cave-bear, the woolly rhinoceros, and other extinct animals.

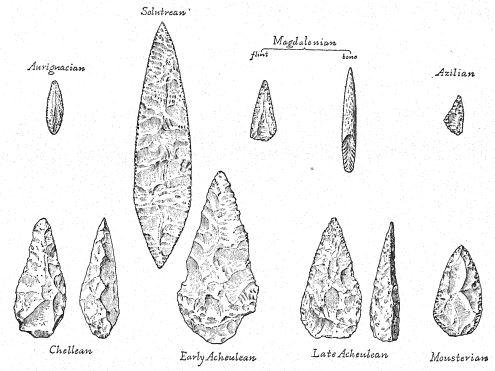

Edouard Lartet, in 1860, began exploring the caverns of the Pyrenees and of Perigord, first examining the remarkable cavern of Aurignac with its burial vault, its hearths, its reindeer and mammoth fauna, its spear points of bone and engravings on bone mingled with a new and distinctive flint culture. This discovery, published in 1861,28 led to the full revelation of the hitherto unknown Reindeer and Art Period of the Old Stone Age, now known as the Upper Palaeolithic. As a palaeontologist, it was natural for Lartet to propose a fourfold classification of the ‘Reindeer Period,’ based upon the supposed succession of the dominant forms of mammalian life, namely:

(d) Age of the Aurochs or Bison.

(c) Age of the Woolly Mammoth and Rhinoceros.

(b) Age of the Reindeer.

(a) Age of the Cave-Bear.

Lartet, in association with the British archeologist, Christy, explored the now famous rock shelters and caverns of Dordogne — Laugerie, La Madeleine, Les Eyzies, and Le Moustier — which one by one yielded a variety of flint and bone implements, engravings and sculpture on bone and ivory, and a rich extinct fauna, in which the reindeer and mammoth predominated. The results of this decade of exploration are recorded in their classic work, Reliquiae Aquitanicae.29 Lartet, observes Breuil,30 clearly perceived the level of Aurignac, where the fauna of the great cave-bear and of the mammoth appears to yield to that of the reindeer. Above he perceived the stone culture of the Solutrean [ p. 14 ] type in Laugerie Haute, and of the Magdalenian type in Laugerie Basse. Lartet also distinguished between the archaeological period of St. Acheul (= Lower Palaeolithic) and that of Aurignac (= Upper Palceolithic).

It remained, however, for Gabriel de Mortillet, the first French archeologist to survey and systematize the development of the flint industry throughout the entire Palaeolithic Period, to recognize that the Magdalenian followed the Solutrean, and that during the latter stage industry in stone reached its height, while dining the Magdalenian the industry in bone and in wood developed in a marvelous manner. Mortillet failed to recognize the position of the Aurignacian and omitted it from his archaeological chronology, which was first published in 1869, Essai de classification des cavernes el des stations sous abri, fondee sur les produits de l’industrie humaine.31

(5) Magdalénien,[10] characterized by a number and variety of bone implements;

(4) Solutreen, leaf-like lance-heads beautifully worked;

(3) Monsterien, flints worked mostly on one side only;

(2) Acheuleen, the ‘langues de chat’ hand-axes of St. Acheul;

(1) Chelléen, bold, primitive, partly worked hand-axes.

Shortly after the Franco-Prussian War, Edouard Piette (b. 1827, d. 1906), who had held the office of magistrate in various tovms in the departments of Ardennes and Aisne, France, and who was already distinguished for his general scientific attainments, began to devote himself especially to the evolution of art in Upper Palaeolithic times, and assembled the great collections which are described and illustrated in his classic work, L’Art pendant l’Age du Renne (1907).32 He first established several phases of artistic evolution in the Magdalenian stage, and only recognized in his later years the station of Brassempouy, not [ p. 15 ] comprehending that the Aurignacian art which he found there underlay the Solutrean culture and was separated by a long interval of time from the most ancient Magdalenian. His distinct contribution to Palaeolithic history is his discovery of the Etage azilien overlying the Magdalenian in the cavern of Mas d’Azil.

Henri Breuil, a pupil of Piette and of Cartailhac, exploring during the decade, 1902-12, chiefly under the influence of Gartailhac, formed a clear conception of the whole Upper Palaeolithic and its subdivisions, and placed the Aurignacian definitely at the base of the series.

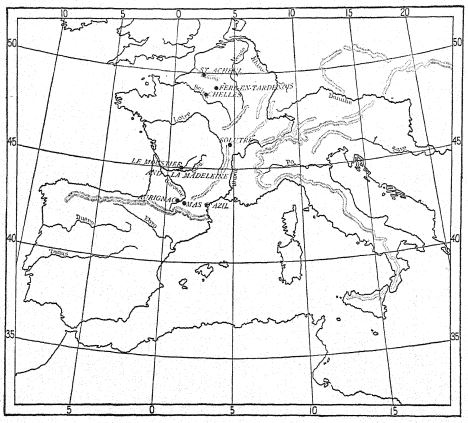

Thus step by step the culture stages of archaeological evolution have been estabhshed and may be summarized with the type stations as follows :

[ p. 16 ]

| ÉTAGE | STATION |

|---|---|

| Tardenoisien | Fere-en-Tardenois, Aisne. |

| Azilien, | Mas d’Azil, Ariège. |

| Magdalenien, | La Madeleine, près Tursac, Dordogne |

| Solutréen | Solutré près Macon, Saône-et-Loire. |

| Aurignacien, | Aurignac, Haute-Garonne. |

| Mousterien, | Le Moustier, commune de Peyzac, Dordogne. |

| Acheuléen, | St. Acheul, pres Amiens, Somme. |

| Chelléen, | Chelles-sur-Marne, Seine-et-Marne. |

| Pre-Chelléen | (= Mesvinien, Rutot), Mesvin, Mons, Belgique. |

These stages, at first regarded as single, have each been subdivided into three or more substages, as a result of the more refined appreciation of the subtle advances in Palaeolithic inventtion and techniciue.

A new impulse to the study of Palaeolithic culture was given in 1895, when E. Riviere discovered examples of Palaeolithic [ p. 17 ] mural art in the cavern of La Mouthe,33 thus confirming the original discovery, in 1880, by Marcelino de Sautuola of the wonderful ceiling frescoes of the cave of Altamira, northern Spain.34 This created the opportunity for the establishment by the Prince of Monaco of the Institut de Paleontologie humaine in 1910, supporting the combined researches of the Upper Palaeolithic culture and art of France and Spain, by Cartailhac, Capitan, Rivière, Boule, Breuil, and Obermaier, and marking a new epoch in the brilliant history of the archaeology of France.

It remained for the prehistory of the borders of the Danube, Rhine, and Neckar to be brought into harmony with that of France, and this has been accomplished with extraordinary precision and fulness through the labors of R. R. Schmidt, begun in 1906, and brought together in his invaluable work, Die diluviale Vorzeit Deutschlands.35

To an earlier and longer epoch belongs the Prepalaeolithic or Eolithic stage. Beginning in 1867 with the supposed discovery by l’Abbé Bourgeois36 of a primordial or Prepalaeolithic stone culture, much observation and speculation has been devoted to the Eolithic37 era and the Eolithic industry, culminating in the complete chronological system of Rutot, as follows :

LOWER QUATERNARY, OR PLEISTOCENE

Strépyan ( = Pre-Chellean, in part).

Mesvinian, culture of Mesvin, near Mons, Belgium (= Pre-Chellean).

Mafflean, culture of Maffle, near Ath, Hennegau.

Reutelian, culture of Reutel, Ypres, West Flanders.

TERTIARY

Prestian, culture of St. Prest, Eure-et-Loire, Upper Pliocene.

Kentian, culture of the plateau of Rent, Middle Pliocene.

Cantalian, culture of Aurillac, Cantal, Upper Miocene or Lo-wer Pliocene.

Fagnian, culture of Boncelles, Ardennes, Middle Oligocene.

Only the Mesvinian stage is generally accepted by archaeologists, and this embraces the prototypes of the Lower Palaeolithic [ p. 18 ] culture, which among most French authors are termed Pre-Chellean or Proto-Chellean. The Eolithic problem has aroused the most animated controversy, in which opinion is divided. A critical consideration of this era, however, falls without the province of the present work.

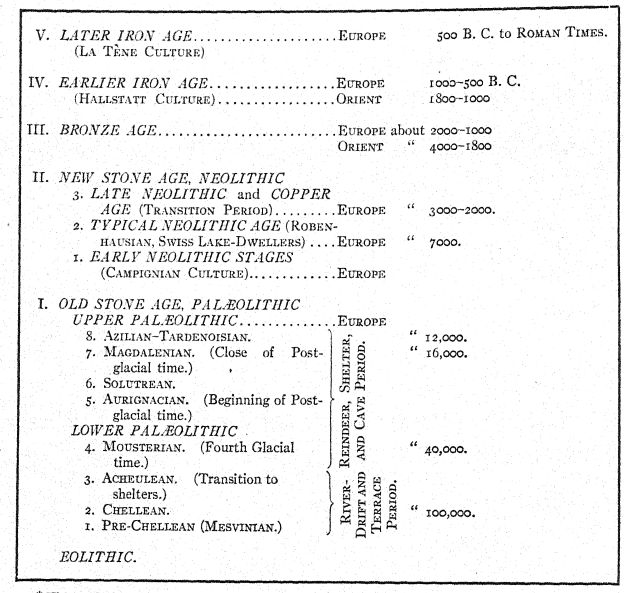

SUCCESSION OF HUMAN INDUSTRIES AND CULTURES[11]

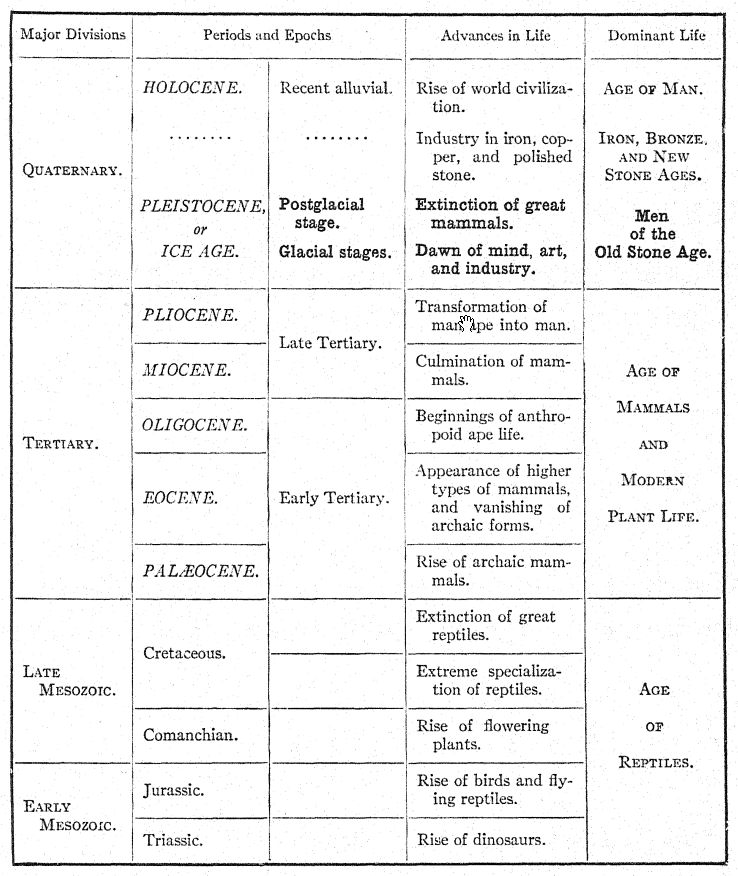

¶ Geologic History of Man

Man emerges from the vast geologic history of the earth in the period known as the Pleistocene, or Glacial, and Postglacial, the ‘Diluvium’ of the older geologists. The men of the Old Stone Age in western Europe are now known through the latter [ p. 19 ] half of Glacial times to the very end of Postglacial times, when the Old Stone Age, with its wonderful environment of mammalian and human life, comes to a gradual close, and the New Stone Age begins with the climate and natural beauties of the forests, meadows, and Alps of Europe as they w’ere before the destroying hand of economic civilization fell upon them.

It is our difficult but fascinating task to project in our imagination the extraordinary series of prehistoric natural events which were witnessed by the successive races of Palaeolithic men in Europe ; such a combination and sequence never occurred before in the world’s history and will never occur again. They centred around three distinct and yet closely related groups of causes. First, the formation of the two great ice-fields centring over the Scandinavian peninsula and over the Alps ; second, the arrival or assemblage in western Europe of mammals from five entirely different life-zones or natural habitats; third, the arrival in Europe of seven or eight successive races of men by migration, chiefly from the great Eurasiatic continent of the East.

Throughout this long epoch western Europe is to be viewed as a peninsula, surrounded on all sides by the sea and stretching westward from the great land mass of eastern Europe and of Asia, which was the chief theatre of evolution both of animal and human life. It was the ‘far west’ of all migrations of animals and men. Nor may we disregard the vast African land mass, the northern coasts of which afforded a great southern migration route from Asia, and may have supplied Europe with certain of its human races such as the ‘Grimaldi.’

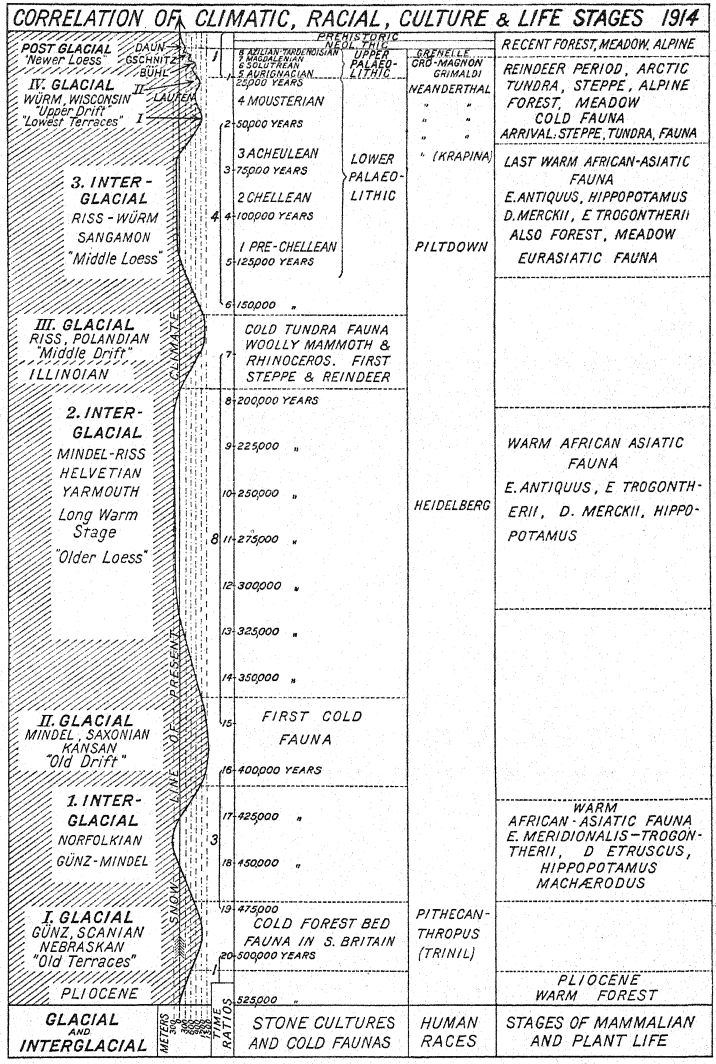

These three principal phenomena of the ice-fields, the mammals, and the human life and industry, together establish the chronology of the Age of Man. In other words, there are four ways of keeping prehistoric time: that of geology, that of palaeontology, that of anatomy, and that of human industry. Geologic events mark the grander divisions of time ; palaeontologic and anatomic events mark the lesser divisions ; while the successive phases of human industry mark the least divisions. The geologic chronology [ p. 20 ] deals with such immense periods of time that its ratio to the animal and to the human chronology is like that of years to hours and to minutes of our own solar time. ■

The Glacial Epoch when first revealed by Charpentier39 and Agassiz,40 between 1837 and 1840, was supposed to correspond to a single great advance and retreat of the ice-fields from various centres. The vague problem of the antiquity of Pliocene man and Diluvial man soon merged into the far more definite chronology of glacial and interglacial man. As early as 1854, Morlot discovered near Dumten, on the borders of the lake of Zurich, a bed of fossil plants indicating a period of south temperate climate intervening between two great deposits of glacial origin. This led to the new conception of cold glacial stages and warm interglacial stages, and Morlot41 himself advanced the theory that there had been three glacial stages separated by two interglacial stages. Other discoveries followed both of fossil plants and mammals adapted to warmer periods intervening between the colder periods. Moreover, successive glacial moraines and ‘drifts,’ and successive river ‘terraces’ were found to confirm the theory of multiple glacial stages. The British geologist, James Geikie (1871-94) marshalled all the evidence for the extreme hypothesis of a succession of six glacial and five interglacial stages, each with its corresponding cold and warm climates. Strong confirmation of a theory of four great glaciations came through the American geologists, Chamberlin,42 Salisbury,43 and others, in the discovery of evidence of four chief glacial and three interglacial stages in northern portions of our own continent. Finally, a firm foundation of the quadruple glacial theory in Europe was laid by the classic researches of Penck and Brückner44 in the Alps, which were published in 1909. Thus the exhaustive research of Geikie, of Chamberlin and Salisbury, of Penck and Bruckner, and finally of Leverett45 has firmly established eight subdivisions or stages of Pleistocene time, namely, four glacial, three interglacial, and one postglacial. These not only mark the great eras of European time but also make possible the synchrony of America with Europe.

[ p. 21 ]

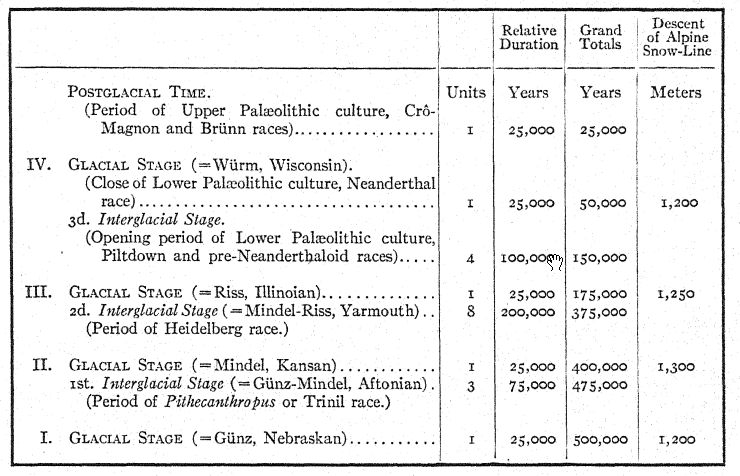

Since most of the skeletal and cultural remains of man can now be definitely attributed to certain glacial, interglacial, or postglacial stages, vast interest attaches to the very difficult problem of the duration of the whole Ice Age and the relative duration of its various glacial and interglacial stages. The following [ p. 22 ] figures set forth the wide variations in opinion on this subject and the two opposite tendencies of speculation which lead to greatly expanded or greatly abbreviated estimates of Pleistocene time :

DURATION OF THE ICE AGE

| 1863. | Charles Lyell,46 Principles of Geology | 800,000 years. |

| 1874. | James, D. Dana.47 Manual of Geology | 720,000 “ |

| 1893. | Charles D. Walcott,48 Geologic Time as Indicated by the Sedimentary Rocks of North America | 400,000 “ |

| 1893. | W. Upham,49 Estimates of Geologic Times, Amer. Jour. Scl, vol. XLV | 100,000 “ |

| 1894. | A. Heim,50 Ueber das absolute Alter der Eiszeit | 100,000 “ |

| 1900. | W. J. Sollas,51 Evolutional Geology | 400,000 “ |

| 1900. | Albrecht Penck,53 Die Alpen im EiszeUalier | 520,000-840,000 |

| 1914. | James Geikie,53 The Antiquity of Man in Europe | 620,000 (min.) |

We may adopt for the present work the more conservative estimate of Penck, that since the first great ice-fields developed in Scandinavia, in the Alps, and in North America west of Hudson Bay a period of time of not less than 520,000 years has elapsed. The relative duration of the subdivisions of the Glacial Epoch is also studied by Penck in his Chronologie des Eisseitalters in den Alpen.52 These stages are not in any degree rhythmic, or of equal length either in western Europe or in North America.

The unit of glacial measurement chosen by Penck is the time which has elapsed since the close of the fourth and last great glaciation; this is known as the Würm in the Alpine region and as the Wisconsin in America. While more limited than the icecaps of the second glaciation, those of the fourth glaciation were still of vast extent in Europe and in this country, so that an estimate of 20,000 to 34,000 years for the unit of the entire Postglacial stage is not extreme. Estimating this unit at 25,000 years and accepting Reeds’s54 estimate of the relative length of time occupied by each of the preceding glacial and interglacial Stages, we reach the following results (compare Fig. 14, p, 41) :

[ p. 23 ]

The Postglacial time divisions are dated by three successive advances of the ice-caps, which broadly correspond with Geikie’s fifth and sixth glaciations ; they are known in the Alpine region as the Bühl, Gschnitz, and Daun. These three waves of cold and humid climate, each accompanied by glacial advances, finally terminated with the retreat of the snow and ice in the Alpine region, the same conditions prevailing as with the present climate. The minimum time estimates of these Postglacial stages and the corresponding periods of human culture, as calculated by Heim,50 Nüesch,55 Penck,52 and many others, are summarized in the Upper Palaeolithic (p. 281).

¶ Geologic and Human Chronology

There are four ways in which the lesser divisions and sequence of human chronology may be dated through geologic or earth-forming events. First, through the age of the culture stations or human remains, as indicated by the ‘river-drifts’ and ‘river terraces’ in or upon which they occur ; second, through the age of the open ‘loess’ stations which are found both on the ‘older terraces’ and on the plateaus between the river valleys ; third, [ p. 24 ] through the age of the shelters and caverns in which skeletal and cultural remains occur; fourth, through the age of the ‘loam’ deposits, which have drifted down on the ‘terraces’ from the surrounding meadows and hills. The men of the Old Stone Age were attracted to these natural camps and dwelling-places both by the abundance of the raw flint materials from which the palaesoliths were fashioned and by the presence of game.

In more than ninety years of exploration only three skeletal relics of man have been found in the ancient ‘river-drifts’; these are the ‘Trinil,’ the ‘Heidelberg,’ and the ‘Piltdown’; in each instance the human remains were buried accidentally with those of extinct animals, after drifting for some distance in the river or stream beds. It is only in late Acheulean times that human burial rites or interments begin and that skeletal remains are found. Owing to the less perishable nature of flint, relies of the quarries and stations are infinitely more common ; they are found both in the river sands and gravels, in the ‘river terraces,’ and in the ‘loess’ stations of the plateaus and uplands. Thus prehistoric chronology is based on observations of the geologist, who in turn is greatly aided by the archaeologist, because the evolution stages of each type of implement are practically the same all over western Europe, with the exception of unimportant local inventions and variations. In brief, the large divisions of time are determined by the amount of work done by geologic agencies ; the comparative age of the various camp sites is determined by their geologic succession, by the mammals and plants which occur in them, and finally by the cultural type of any industrial remains that may be found.

¶ Times of the ‘High’ and ‘Low’ River ‘Terraces’

The so-called ‘terrace’ chronology is to be used by the prehistorian with caution, for it is obvious that the ‘terraces’ in the different river-valleys of western Europe were not all formed at the same time; thus the testimony of the ‘terraces’ is always to be checked off by other evidence.

[ p. 25 ]

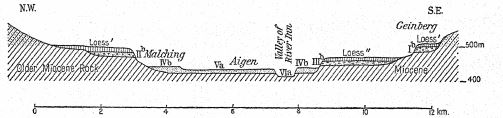

As to the origin of the sands and gravels which compose the ‘terraces’ we know that the glacial stages were periods of the wearing away of vast materials from the summits and sides of the mountains, which were transported by the rivers to the valleys and plains. These vast deposits of glacial times spread out over the very broad surfaces of the pristine river-bottoms, which in many valleys it is important to note were from loo to 150 feet above the present levels. The diminished and contracted streams of interglacial times cut into these ancient river beds, forming narrower channels into which they transported their own materials. Thus, as the successive ‘river terraces’ were formed, a descending series of steps was created along the sides of the valleys. In many valleys there are four of these ‘terraces,’ which may correspond with several glacial stages; in other valleys there are only three; in others, again, like the valley of the River Inn which flows past Innsbruck in the Tyrol (Fig. 6), there are five ‘terraces,’ while in the valley of the Rhine above Basle there are six, corresponding, it is believed, with the materials brought down by the four great glaciations and with the river levels of Postglacial times. In general, therefore, the ‘high terraces’ are the oldest ones, that is, they are composed of [ p. 26 ] materials brought down during the pluvial periods of the First, Second, and Third Glacial Stages, while the Tower terraces’ and the ‘lowest terraces’ in the alpine regions are composed of materials borne by the great rivers of the Fourth Glacial and Postglacial Stages. In the region around the Alps the ‘higher terraces’ are products chiefly of the third glaciation ; in the valley of the Rhine they are visible near Basle. On the upper Rhine the ‘low terraces’ are products of the fourth glaciation; they cover vast surfaces and contain remains of the woolly mammoth (E. primigemus), an animal distinctive of Fourth Glacial and Postglacial times.

Ib. Very broad river deposits of First Glaciation, on the first ctosion level, covered with the ‘Upper Loess’ of the Second Interglacial Stage.

IIb. Somewhat narrower river deposits of Second Glaciation on the second erosion level.

IIIb. Still narrower river terraces of the Third Glaciation on the third erosion level, covered wdth the ‘Lower Loess’ of the Third Interglacial Stage.

IVb. Fourth or lowest terrace of the Fourth Glaciation on the fourth erosion level.

Va. Erosion terraces, Achen.

VIa. Post-Bühl erosion.

Loess'. ‘Upper Loess’ of Second Interglacial. Loess", ‘Lower Loess’ of Third Interglacial.

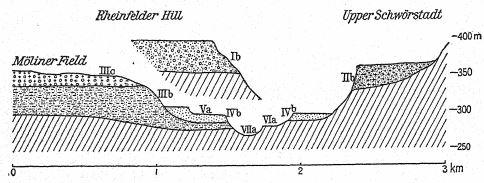

Ib. Out wash of the First Glaciation— Gunz — Deposits on the first erosion level.

IIb. Outwash of the Second Glaciation— Mindel — Deposits on the second erosion level.

IIIb. Outwash of the Third Glaciation— Riss — Deposits on the third erosion level.

IVb. Outwash of the Fourth Glaciation — ^Wtimi — Deposits on the fourth erosion level.

Va. Erosion terrace, Achen oscillation — fifth erosion level.

VIa/VIIa. Post-Bühl erosion— sixth and seventh erosion levels.

IIIc. Moraine of the Third Glaciation — Riss.

The section of the Rheinfelder Hill lies 3 km. west from the Moliner Field.

More remote from the glacial regions, but equally subject to the inundations of glacial times are the ‘high terraces’ along the River Seine, which are ninety feet above the present level of the river and contain the remains of mammals characteristic of the First Interglacial Stage, such as the southern elephant (E. meridionalis), while the Tow terraces’ along the Seine are only fifteen feet above the present level of the river and contain mammals belonging to the Third Interglacial Stage. Similarly, [ p. 27 ] the ‘high terraces’ of the River Eure contain mammals of First Interglacial times, such as the southern elephant (E. meridionalis) and Steno’s horse (E. stenonis) ; these fossils occur in coarse river sands and gravels which were deposited by a broad stream that flowed at least ninety feet above the present waters of the Eure.

The human interest which attaches to these dry facts of geology appears especially in the valleys of the Somme and the Marne in northern France; here again we find ‘high terraces,’ ‘middle terraces,’ and ‘low terraces’; the latter are still subject to flooding. In the deep gravels upon each of these terraces we find the first proofs of human residence, for here occur the earliest Pre-Chellean and Chellean implements associated with the remains of the hippopotamus, of Merck’s rhinoceros, and of the straight-tusked elephant (E. antiqum), together with mammals which are characteristic both of Second and Third Interglacial times.

This raises a very important distinction, which is often misunderstood; namely, between the materials composing the original terraces and those subsequently deposited upon the terraces. It appears to be in the latter that human artifacts are chiefly, if not exclusively, found.

¶ Times of the Loam Stations

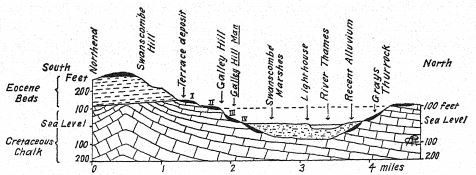

The ‘loam’ which washes down over the original sand and gravel ‘terraces’ from the surrounding hills and meadows is of much later date than the ‘terraces’ themselves, and the archaeologist in the valley of the Somme as well as in that of the Thames may well be deceived unless he clearly distinguishes between the newer deposits of gravels and of loams and the far older gravels and river sands which compose the original ‘terraces.’ This is well illustrated by the observations of Commont on the section of St. Acheul.56 The loams and brick-earth are of much more recent age than the original gravels and sands of the ‘terraces’ which they overlap and conceal; the lowest and oldest ‘loam’ [ p. 28 ] (limon fendillé) contains Acheulean flints, while the overlying ‘loam’ contains Mousterian flints. Although occurring on the ‘higher terraces,’ these flints are of somewhat later date than the primitive Chellean flints which occur in the coarse gravels and sands that have collected upon the very lowest levels (Fig. 59).

A similar prehistoric inversion doubtless occurs in the ‘terraces’ of the Thames, for materials on the ‘highest terrace’ (Fig. 8) contain Acheulean flints, while materials on the ‘lowest terrace’ belong to a much more recent age.

We have no record of a single Palceolithic station found in the true original sands and gravels of the ‘higher terraces’ in any part of Europe; only eoliths are found on the ‘high terrace’ levels, as at St. Prest.

The earliest palseoliths occur in the gravels on both the ‘middle’ and ‘upper terraces’ of the Somme and the Marne, proving that the gravels were deposited long subsequent to the cutting of the original terraces. Geikie,57 moreover, is of the opinion that the valley of the Somme has remained as it is since early Pleistocene times, and that even the ‘lowest terrace’ here was completed at that period ; this is contrary to the view of Commont, who considers that this ‘lowest terrace’ belongs to Third Interglacial times ; a restudy of the stations along the Thames may throw light upon this very important difference of opinion.

[ p. 29 ]

¶ Times of the ‘Loess’ Stations

The glacial stages were generally times of relatively great humidity, of heavy rain and snow fall, of full rivers charged with gravels and sands, and with loam the finest product of the erosive action of ice upon the rocks. This loam on the barren wastes left bare by the glaciers or on the river borders and overflow basins was retransported by the winds and laid down afresh in layers of varying thickness known as ‘loess.’ There was no ‘loess’ formation either in Europe or America during the humid climate of First Interglacial times, but during the latter part of the Second Interglacial Stage, again toward the close of the Third Interglacial Stage, and finally during Postglacial times there were periods of arid climate when the ‘loess’ was lifted and transported by the prevailing winds over the Terraces’ and [ p. 30 ] plateaus and even to great heights among the mountain valleys. As observed by Huntington58 in his interesting book The Pulse of Asia, even at the present time there are districts where we find ‘loess’ dust filling the entire atmosphere either during the heated months of summer or during the cold months of winter.

In Pleistocene Europe there were at least three warm or cold arid periods, accompanied in some phases by prevailing westerly winds,59 in which ‘loess’ was widely distributed over northern Germany, covering the ‘river terraces,’ plateaus, and uplands bordering the Rhine and the Neckar. These ‘loess’ periods can be dated by the fossil remains of mammals which they contain, also by the stations of the flint quarries in different culture stages. Thus we find late Acheulean implements in drifts of ‘loess’ at Villejuif, south of Paris. Among the most famous stations of late Acheulean times is that of Achenheim, west of Strasburg, and not far distant is the ‘loess’ station of Mommenheim, of Mousterian times ; both belong to the period of the fourth glaciation. An Aurignacian ‘loess’ station is that of Willendorf, Austria.

¶ Times of the Limestone Shelters and Caverns

Beginning in the late or cold Acheulean period, the Paleolithic hunters commenced to seek the warm or sheltered side of deepened river-valleys, also the shelter afforded by overhanging cliffs and the entrances of caverns. It is quite probable that during the warm season of the year they still repaired to their open flint quarries along the rivers and on the uplands ; in fact, the river Somme was a favorite resort through Acheulean into Mousterian times.

In general, however, the open rivers and plateaus were abandoned, and all the regions of limestone rock favorable to the formation of shelter cliffs, grottos, and caverns were sought out by the early Paleolithic men from Mousterian times on ; and thus from the beginning of the Mousterian to the close of the Upper Paleolithic their lines of migration and of residence followed the [ p. 31 ] exposures of the limestones which had been laid dowm by the sea in bygone geologic ages from Carboniferous to Cretaceous times. The upper valleys of the Rhine and Danube traversed the white Jurassic limestones which are again exposed in a broad band along the foot-hills of the Pyrenees, extending far west to the Cantabrian Alps of modern Spain. In Dordogne the great horizontal plateau of Cretaceous limestone had been dissected by branching rivers, such as the Vézère, to a depth of two hundred feet. Under overhanging cliffs long rock shelters were formed, such as that of the Magdalenian station at La Madeleine.

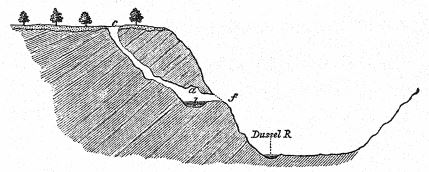

c. Entrance of percolating waters from above.

/. Exit from the grotto.

a-b. Interior of the cavern.

Many caverns were formed, some of them in early Pleistocene times, by water percolating from above and (Fig. 11) resulting in subterranean streams which issued at the entrance; this formed the expanded grotto, sometimes a chamber of vast dimensions, such as the Grotte de Gargas. Outside of this, again, may be an abri or shelter of overhanging rock. In other cases the rock shelter is found quite independent of any cave.

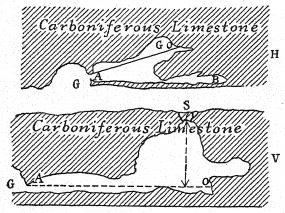

V. Vertical section of limestone cliff showing (S) waters percolating from above; (A-O) interior of the cavern; and (G) grotto entrance, original exit of the cavern waters. H. Horizontal section of the same cavern showing the (G) grotto entrance and (A, G, O, B) the ramifications of the cavern.

Where the glaciers or ice-caps passed over the summits of the hills the subglacial streams penetrated the limestone of the mountain and formed vast caverns, such as that of Niaux, near the river Ariege. Here a nearly horizontal cavern was formed, extending half a mile into the heart of the mountain. The material [ p. 32 ] with which the floors of the caverns are covered is either a fine cave loam or the insoluble remainder of the limestone forming a brown or gray clayey substance. The Magdalenian artists produced drawings on these soft clays and, in rare instances, used them for modelling purposes, as in the Tuc d’Audoubert. The sands and gravels were also swept in from the streams above and carried by strong currents along the wall surfaces, smoothing and polishing the limestone in preparation for the higher forms of Upper Palaeolithic draughtsmanship and painting.

It would appear that the majority of the caverns were formed in pluvial periods of early glacial times; the formation had been completed, the subterranean streams had ceased to flow, and the interiors were relatively dry and free from moisture in Fourth Glacial and Postglacial times, when man first entered them. There is no evidence, however, that the cavern depths were generally inhabited, for the obvious reason that there was no exit for the smoke; the old hearths are invariably found close to or outside of the entrance, the only exception being in the entrance to the great cavern of Gargas, where there is a natural chimney for the exit of smoke. There was no cave life, strictly speaking — it was grotto life ; the deep caves and caverns were probably penetrated only by artists and possibly also by magicians or priests. It is in the abris or shelters in front of the grottos and in the floors of the caverns that remarkable prehistoric records are found from late Acheulean times to the very close of [ p. 33 ] the Palaeolithic, as in the wonderful grotto in front of the cave at Castillo, near Santander. Thus, as Obermaier60 observes : “In Chellean times primitive man was a care-free hunter wandering as he chose in the mild and pleasant weather, and even the colder climate of the arid ‘loess’ period of the late Acheulean ivas not sufficient to overcome his love of the open; he still made his camp on the plains at the edge of the forest, or in the shelter of some overhanging cliff.” Only in rare instances, as at Castillo, were the Acheulean hearths brought within the entrance fine of the grotto.

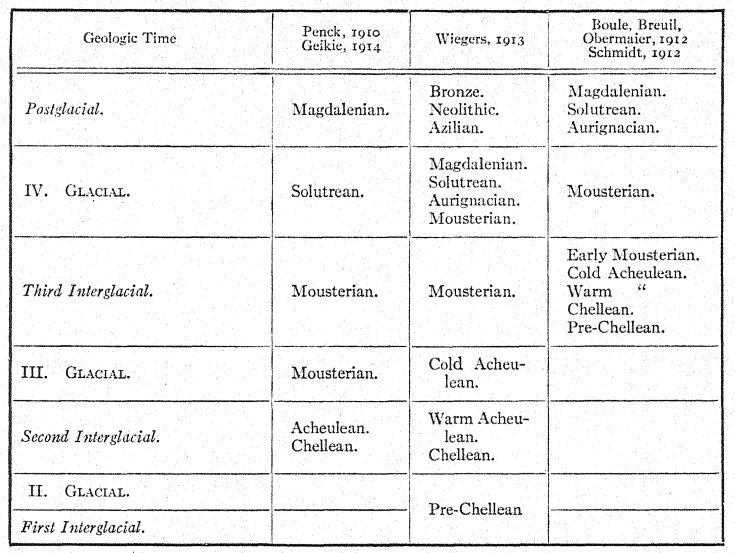

The right-hand column represents the theory adopted in this volume.

Interpretation of these four kinds of evidence as to the antiquity of human culture in western Europe still leads to widely diverse opinions. On the one hand, we have the high authority of Penck61 and Geikie62 that the Chellean and Acheulean cultures are as ancient as the second long warm interglacial period. [ p. 34 ] An extreme exponent of the same theory is Wiegers,63 who would carry the Pre-Chellean back even into First Interglacial times. On the other side, Boule,64 Schuchardt,65 Obermaier,66 Schmidt,67 and the majority of the French archaeologists place the beginning of the Pre-Chellean culture in Third Interglacial times.

In favor of the latter theory is the strikingly close succession of the Lower Palaeolithic cultures in the valley of the Somme, followed by an equally close succession from Acheulean to Magdalenian times, as, for example, in the station of Castillo. It does not appear possible that a vast interval of time, such as that of the third glaciation, separated the Chellean from the Mousterian culture.

On the other hand, in favor of the greater antiquity of the Pre-Chellean and Chellean cultures may be urged their alleged association in several localities with very primitive mammals of early Pleistocene type, namely, the Etruscan rhinoceros, Steno’s horse, and the saber-tooth tiger, as witnessed in Spain and in the deposits of the Champs de Mars, at Abbeville.

It is true, moreover, that at points distant from the great ice-fields, like the valley of the Somme and that of the Marne, we have no other means of separating glacial from interglacial times than that afforded by the deposition and erosion of the ‘terraces’ ; in fact, the interpretation of the age of the cultures may be similar to that applied to the age of the mammalian fauna. There are no proofs of periods of severe cold in western Europe in any country remote from the glaciers until the very cold steppe-tundra climate immediately preceding the fourth glaciation swept the entire land and drove out the last of the African- Asiatic mammals.

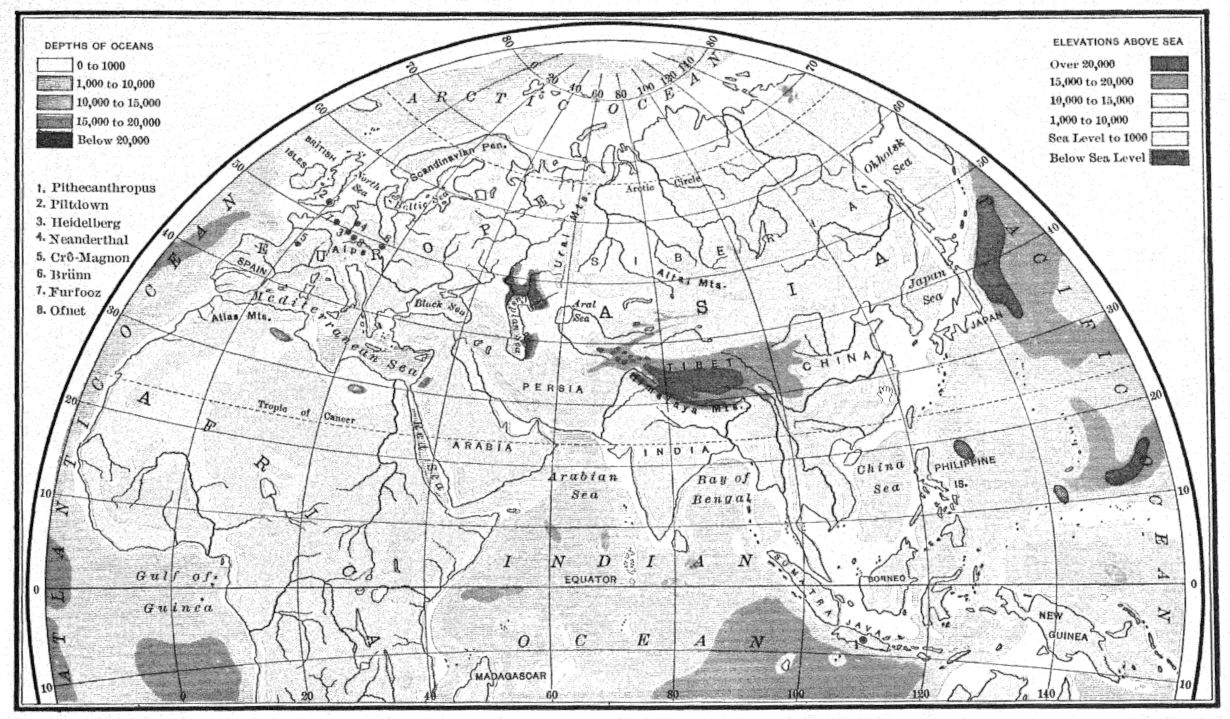

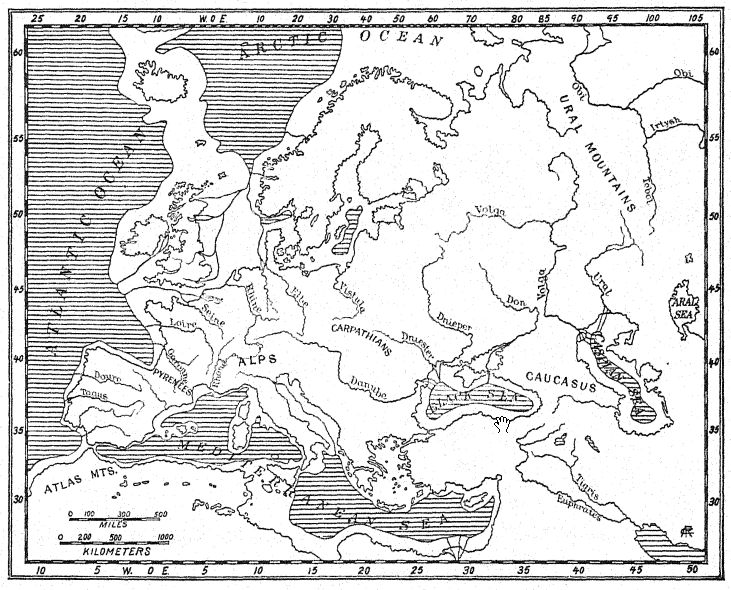

¶ Geographic Changes

The migrations of mammals and of races of men into western Europe from the Eurasiatic continent on the east and from Africa on the south were favored or interrupted by the periods of elevation or of subsidence of the coastal borders of the AEgean, Mediterranean, and North Seas, and also of the Iberian and [ p. 35 ] British coast-lines. The maximum period of elevation of the coastal borders, as represented in the accompanying map (Fig. 12), never occurred in all portions of the continent of Europe at the same time, because there were oscillations both on the northern and southern coasts of Europe and Africa. The early Pleistocene, especially the period of the First Interglacial Stage, was one of elevation remarkable for the broad land bridges which brought the animal life of Europe, Africa, and Asia together. The Mediterranean coast rose 300 feet. Land bridges from Africa were formed at Gibraltar and over to the island of Sicily, so that for the time there was a free migration of mammalian life north and south. It is to this that western Europe owes the majestic [ p. 36 ] mammals of Asiatic and African life which dominated the native fauna.

In general, the elevation of the continent took place during interglacial, the subsidence during glacial times, but Great Britain appears to have been almost continuously elevated and a part of the continent, and was certainly so during the Third Interglacial, Fourth Glacial, and Postglacial Stages, because there was a free migration of animal life and of human culture. The Lower Palaeolithic peoples of Pre-Chellean and Chellean times wandered at will from the valley of the Somme to the not far distant valley of the Thames, interchanging their weapons and inventions. The close proximity of these stations is well illustrated in the admirable map (Fig. 56) prepared under the direction of Lord Avebury (Sir John Lubbock). The relation which elevation and subsidence respectively bear to the glacial and interglacial stages is believed to be as follows:

ELEVATION, emergence of the coast-lines from the sea, broad land connections facilitating migration, retreat of the glaciers, deepening of the river-valleys, and cutting of terraces. Arid continental climate and deposition of ‘loess.’

SUBSIDENCE, submergence of the coast-lines and advance of the sea, interruption of land connections and of migration routes, advance of the glaciers, filling of the river-valleys with the products of glacial erosion, the sand and gravel materials of w’hich the ‘terraces’ are composed, and subglacial erosion of the loam, from which in arid periods the ‘loess’ is derived.

Subsidence was the great feature of closing glacial times both in Europe and America. During the Fourth Glacial and Postglacial Stages the Black and Caspian Seas and the eastern portion of the Mediterranean were deeply depressed, while the British Isles were still connected with France, but by a narrower isthmus than that of early interglacial times. The scattered stations of Upper Palaeolithic culture found in the British Isles include one Aurignacian, one Solutrean, two Magdalenian, and two Azilian; this shows that travel communication with the continent continued throughout that period, in all probability [ p. 37 ] by means of a land connection. In late Neolithic times the English Channel was formed. Great Britain became isolated from Europe, and Ireland lost its land connection first with Wales and then with Scotland.

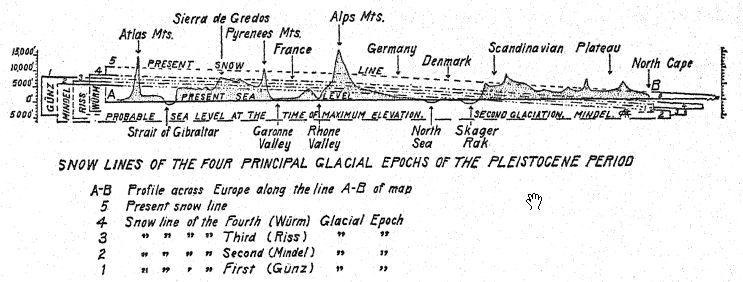

¶ Changes of Climate

Penck68 estimates the intensity of the cold and of the humidity which prevailed during the glacial stages by the descent of the snow-hne in the Alps, which in the two periods of greatest glaciation reached from 1,200 m. (3,937 ft.) to 1,500 m. (4,921 ft.) below the present snow-level, with the consequent formation of vast ice-caps hung with glaciers which flowed great distances down the valleys of the Rhône and of the Rhine and left their moraines at very distant points. The moraines and drifts of the lesser glaciations, such as the first and fourth, stand considerably within the boundaries of these outer moraines and drift fields. On the contrary, the warmer climates of interglacial times are indicated by the sun-loving plants found at Hötting, along the valley of the Inn, in the Tyrol, which are proofs of a temperature higher than the present and of the ascent of the snow-line 300 m. (984 ft.) above the existing snow-level of the Alps.

[ p. 38 ]

The alternation of the cold climates of the glacial stages with the warm temperate climates of the interglacial stages formed great oscillations of temperature (Figs. 13, 14). The fossil plant life indicates that during the periods of the First, Second, and Third Interglacial Stages the climate of western Europe was cooler than it had been during the preceding Pliocene Epoch and somewhat warmer than it is at the present time in the same localities. During the First, Second, and Third Glacial Stages there was certainly a marked lowering of temperature in the regions bordering the great glacial fields. This is indicated by the arrival in the northern glacial border regions of animals and plants adapted to arctic and subarctic climates.

It has been generally believed that the whole of western Europe was extremely cold during these glacial stages, and that the heat-loving animals, the southern elephants, rhinoceroses, and hippopotami, were driven to the south, to return only with the renewed warmth of the next interglacial stage.

There is, however, no proof of the departure of these supposedly less hardy mammals nor of the spread over Europe of the more hardy arctic and steppe types until the advent of the Fourth Glacial Stage. Then, for the first time, all western Europe north of the Pyrenees experienced a general fall of temperature, and conditions of climate prevailed such as are now found in the arctic tundra regions of the north and in the high steppes of central Asia, which are swept by dry and cold winter winds. Fluctuations of temperature, of moisture, and of aridity in Pleistocene time, are evidenced not only by the rise and fall of the snow-line and the advance and retreat of the ice-caps but also by the appearance of plant and animal life in the periods of the ‘loess’ deposition, indicating the following cycles of climatic change as witnessed from beginning to end of the Third Interglacial Stage :

IV. Glacial maximum, cold and moist climate, arctic and cold steppe fauna and flora.

Cool and dry steppe climate, wide-spread deposition of ‘loess.’

[ p. 39 ]

Interglacial maximum, a long period of warm temperate forest and meadow conditions.

Glacial retreat, cool and moist climate bordering the glacial regions.

III. Glacial maximum, cold and humid climate bordering the glaciers, favorable to arctic and subarctic plant and animal life.

That great fields of ice and advancing glaciers alone do not constitute proof of very low temperatures is shown at the present time in southeastern Alaska, where very heavy snowfall or precipitation causes the accumulation of vast glaciers, although the mean annual temperature is only 10° Fahr. (5.56° C.) lower than that of southern Germany. Neumayr69 estimated that during the Ice Age there was a general lowering of temperature in Europe of not more than 6° C. (10.8° Fahr.), and held that even during the glacial advances a comparatively mild climate prevailed in Great Britain. Martins70 estimated that a lowering of the temperature to the extent of 4° C. (7.2° Fahr.) would bring the glaciers of Chamonix down to the level of the plain of Geneva. Penck estimates that, all the atmospheric conditions remaining the same as at present, a fall of temperature to the extent of 4° to 5° C. would be sufficient to bring back the Glacial Epoch in Europe. These moderate estimates entirely agree with our theory that animals of African and Asiatic habit flourished in western Europe to the very close of the Third Interglacial Stage, and that then for the first time the warm fauna, or faune chaude, gradually disappeared.

Similarly the hypothesis of extremely warm or subtropical conditions prevailing in interglacial times as far north as Britain, which originated with the discovery of the northerly distribution of the hippopotami and rhinoceroses, animals which we now associate with the torrid climate of Africa, is not supported by the study either of the plant life of interglacial stages or by the history of the animals themselves. It is quite probable that both the hippopotami and the rhinoceroses of the ‘warm fauna’ [ p. 40 ] were protected by hairy covering, although not by the thick undercoating of wool which protected the woolly rhinoceros and woolly mammoth, animals favoring the borders of glaciers and flourishing during the last very cold glacial and Postglacial periods.

The combined evidence from all these great events in western Europe leads us to conclusions somewhat different from those reached by Penck as to the chronology of human culture. In the chart (Fig. 14) on the opposite page, prepared by Dr. C. A. Reeds in collaboration with the author, a new correlation of geologic, climatic, human, industrial, and faunal events is presented. The great waves of glacial advance and retreat (oblique shading) are based upon Penck’s estimates of the rise and fall of the snow-line (vertical dotted hues) in the Swiss Alps. (Compare Fig. 13.) The length of these waves corresponds with the relative duration of the glacial and interglacial stages as estimated by the varying amounts of erosion and deposition of materials. The entire Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age is thus seen to occupy not more than 125,000 years, or only the last quarter of the Glacial Epoch, which is estimated as extending over a period of 525,000 years. The present opinion of the leading archaeologists of France and Germany, which is shared by the author, is that the Pre-Chellean industry is not older than the Third Interglacial Stage. As the Piltdown man was found in deposits containing Pre-Chellean implements, he probably lived in the last quarter of the Glacial Epoch, and not in early Pleistocene times as estimated by some British geologists. This causes us to regard the Piltdown remains as more recent than the jaw of Heidelberg, which all authorities agree is probably of Second Interglacial Age. According to our estimates the Heidelberg man is nearly twice as ancient as the Piltdown man, while Pithecanthropus (Trinil Race) is four times as ancient. Yet the Piltdown man must still be regarded as of very great antiquity, for he is four times as ancient as the final type of Neanderthal man belonging to the Mousterian industrial stage. The various archaeologic and paleontologic evidences for this general correlation, theory of the Glacial Epoch are fully discussed in the succeeding chapters of this volume.

[ p. 41 ]

[ p. 42 ]

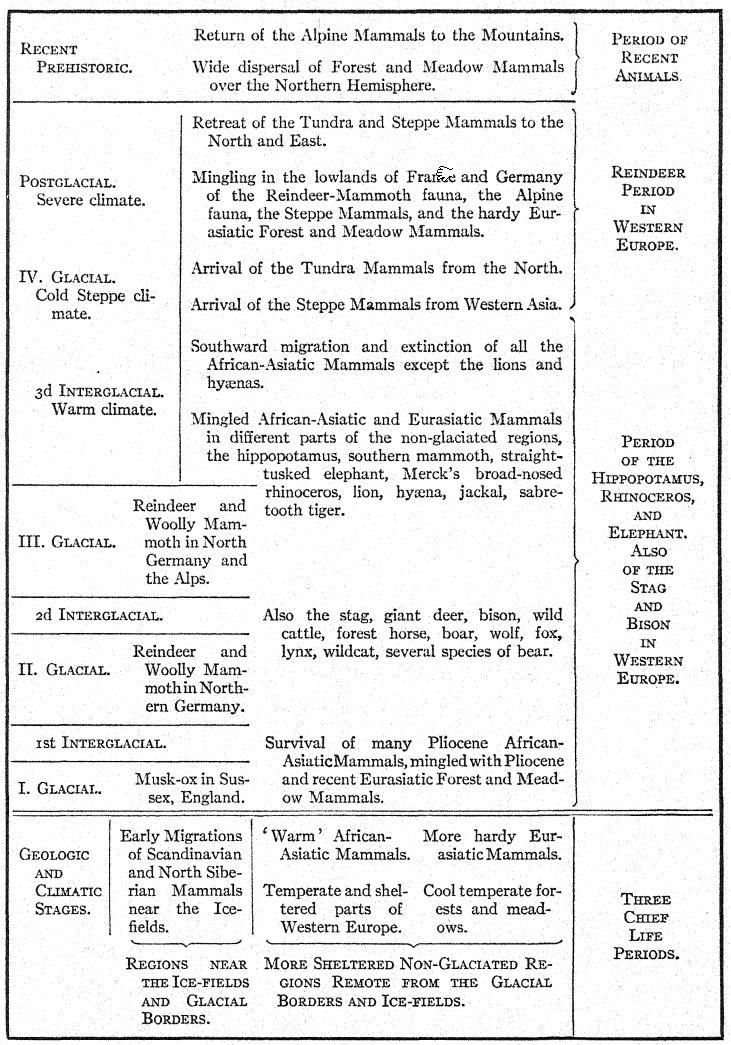

¶ Mammals of Five Distinct Geographic Regions

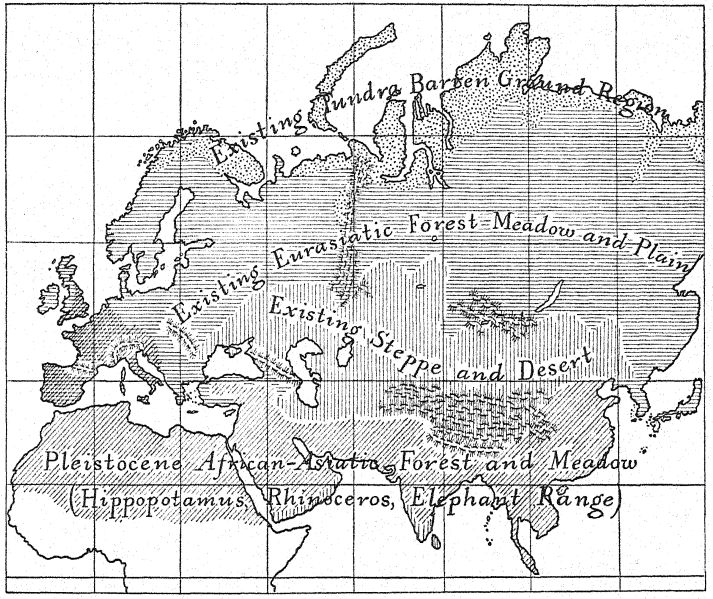

(Compare Color Map, PL II, and Fig. 15 )

As we have already observed, during the whole history of mammalian life in various parts of the world never did there prevail conditions so unusual and so complex as those which surrounded the men of the Old Stone Age in Europe. The successive races of Palaeolithic men in Europe were all flesh eaters, depending upon the chase. The mammals, first pursued only for food, utensils, and clothing, finally became subjects of artistic appreciation and endeavor which resulted in a remarkable aesthetic development.

From the beginning to the end of Palaeolithic times the various races of man witnessed the assemblage in Europe of animals indigenous to every continent on the globe except South America and Australia and adapted to every climatic life-zone, from the warm and dry plains of southern Asia and northern Africa to the temperate forests and meadows of Eurasia; from the heights of the Alps, Himalayas, Pyrenees, and Altai Mountains to the high, arid, dry steppes of central Asia with their alternating heat of summer and cold of winter; from the tundras or barren grounds of Scandinavia, northern Europe, and Siberia to the mild forests and plains of southern Europe.71 Members of all these highly varied groups of animals had been evolving in various parts of the northern hemisphere from the Eocene Epoch onward. In Pliocene times they had become thoroughly adapted to their various habitats. Throughout early Pleistocene times, with the increasing cold extending southward from the arctic circle, such mammals as the elephant, rhinoceros, musk-ox, and reindeer had become thoroughly adapted to the chmate of the extreme north. There is every reason to believe that when these tundra quadrupeds first arrived in Europe, during early midglacial stages, they had already acquired the heavy coat of hair [ p. 43 ] and undcrcoating of wool, such as now characterizes the musk ox, one of the living representatives of this northern launa.

[ p. 44 ]

The five great sources of mammalian migration into western Europe in Pleistocene times were accordingly as follows:

- WARM PLAINS of northern Africa and of southern Asia. “African-Asiatic” fauna — hippopotamus, rhinoceros, elephant.

- TEMPERATE MEADOWS AND FORESTS of Europe and Asia. “Eurasiatic” fauna — deer, bison, horse.

- HIGH, COOL MOUNTAIN RANGES — Alps, Pyrenees, Caucasus, Urals. Fauna — chamois, ibex, ptarmigan. (See Fig. 185.)

- STEPPES AND DESERTS. Dry, elevated plateaus and steppes of eastern Europe and central Asia. Fauna — desert ass and horse, saiga antelope, jerboa. (See Fig. 186.)

- TUNDRAS AND BARREN GROUNDS within or near the arctic circle. Fauna — reindeer, musk-ox, arctic fox. (See Figs. 95 and 96.)

(Compare Figs. 14 and 15.)

In the warm plains, forests, and rivers of southern Asia and northern Africa there developed the elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotami, lions, hyaenas, and jackals, which, taken together, may be known as the African-Asiatic fauna. It contains altogether fourteen species of mammals. The great geographic area from the far east to the far west over which ranged similar or identical species of these pachyderms and carnivores is indicated by the oblique lines in the geographic chart (Fig. 15).

The north temperate belt of Asia and Europe, with its hardy forests and genial meadows, was the home of the even more highly varied Eurasiatic Forest and Meadow fauna. This includes twenty-six or more species. Of these the red deer, or stag, was most characteristic of the forests and the bison and wild cattle[12] of the meadows. Even at the very beginning of Pleistocene times there appear the stag, the wild boar, and the roe-deer with their natural pursuers, the wolf and the brown bear. F rom the northern woods came the moose and the wolverene. Most of these mammals were so similar to existing forms that the older naturalists [ p. 45 ] placed them in existing species, but the tendency now is to separate them or place them in distinct subspecies. Mingled with these forest and meadow mammals were a few others which have since become extinct, such as the giant deer (Megaceros), the giant beaver (Trogontherium), and the primitive forest and meadow horses. From this region also there developed the cave-bear (Ursus spdaus). Certainly it is astoni.shing to find the remains of these mammals mingled with those from southern Asia and Africa, as is frequently the case. In early glacial times the [ p. 46 ] bison and wild cattle mingled freely with the hippopotami and rhinoceroses, but in late glacial and Postglacial times they occurred as companions of the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. In prehistoric times they survived with the mammals brought from the Orient by the Neolithic agriculturists.

During a great glaciation, but especially during the severe climate of late Pleistocene times, the Alpine mammals were driven down from the heights into the plains and among the lower mountains and foot-hills. Thus the ibex, chamois, and argali sheep from the Altai Mountains are represented both in drawing and in sculpture by the men of the Reindeer Period.

Still more remarkable is the arrival in Europe of the Steppe Fauna of Russia and of western Siberia, mammals which now survive in the vast Kirghiz steppes, east of the Caspian Sea and the Ural Mountains, where the climate is one of hot, dry summers and prolonged cold winters, with sweeping dust and snow storms. These animals are very hardy, alert, and swift of foot, such as the jerboa, the saiga antelope, the wild asses, and the wild horses, including the Przewalski type, which still survives in the desert of Gobi. From this region also came the Elasmothere (E. sibiricum), with its single giant horn above the eyes. Very distinctive of the faima frequenting the caverns are the small rodents, including the dwarf pikas, the steppe hamsters, and the lemmings. These animals were attracted into Europe during the ‘steppe’ and ‘loess’ periods of cold, dry climate.

The advance of the great Scandinavian glaciers from the north crowded to the south the Tundra or Barren Ground fauna of the arctic circle. The herald of this fauna during the First Glacial Stage was the musk-ox, which appears in Sussex, and then came the reindeer of the existing Scandinavian type. These animals are followed by the woolly mammoth (E. primigenius) and the woolly rhinoceros (D. antiquitatis) with their panoply of hair and wool which had long been developing in the north. Finally in the Fourth Glacial Stage arrived the lemming of the river Obi, also the more northern banded lemming, the arctic fox, the wolverene, and the ermine, as well as the arctic hare. [ p. 47 ] These tundra mammals for a short period mingled in places with survivors of the African-Asiatic fauna, such as Merck’s rhinoceros and the straight-tusked elephant (E. antiquus). In general, they swept southward as far as the Pyrenees over country which had long been enjoyed by the African-Asiatic mammals, while the hippopotami and the southern elephants retreated still farther south and became extinct.

The only survivors of the great African-Asiatic fauna in Fourth Glacial and Postglacial times were the hyaenas (H. crocuta spelcea) and the lions (Felis leo spelcea). The lion frequently appears in the drawings of the cavemen.

The various species belonging to these five great faunae apparently succeed each other, and wherever their remains are mingled with the palaeoliths, as along the rivers Somme, Marne, and Thames, or in the hearths of the shelters and caverns, they become of extreme interest both in their bearing on the chronology of man and on the development of human culture, art, and industry. They also tell the story of the sequence of climatic conditions both in the regions bordering the glaciers and in the more temperate regions remote from the ice-caps. Thus they guide the anthropologist over the difficult gaps where the geologic record is limited or undecipherable. The general succession of these great faunas is illustrated in Fig. 14 and also in the above table.

¶ Bibliography

(1) Lamarck, 1815.1.

(2) Schaaffhauseii, 1858.1.

(3) Darwin, C., 1909.2.

(4) Lamarck, 1809.1.

(5) Lyell, 1863.1, pp. 84-89.

(6) Darwin, C., 1871.1, p. 146.

(7) Darwin, C., 1909.1, p. 158.

(8) Retzius, A., 1864.1, p. 27.

(9) Op. cit., p. 166.

(10) Broca, 1875.1,

(11) Schwalbe, G., 1914. i, p. 592.

(12) Cartailhac. 1903.1.

(13) Dechelette, 1908.1, vol. I.

(14) Reinach, S., 1889.1.

(15) Schmidt, 1912.1.

(16) Avebury, 1913.1.

(17) Eccardus, 1750.1.

(18) Mahudel, 1740.1.

(19) Buckland, 1824.1.

(20) Godwin-Austen, 1840.1.

(21) Christol, 1829.1.

(22) Schmerling, 1833.1.

(23) Boucher de Perthes, 1846.1,

(24) Op. cit.

(25) Rigollot, 1854.1.

(26) Lubbock, 1862.1.

(27) Avebury, 1913.1, pp. 2, 3.

(28) Lartet, 1861.1,

(29) Lartet, 1875.1.

(30) Breuil, 1912. 7, p. 165.

(31) de Mortillet, 1869.1.

(32) Piette, E., 1907.1.

[ p. 48 ]

(33) Rivière 1897.1.

(34) de Sautuola, 1880.1.

(35) Schmidt, 1912.1.

(36) Bourgeois, 1867.1.

(37) Schmidt, op. cit., p. 5.

(38) Obermaier, 1912.1, pp. 170-174; 316-320; 332, 545

(39) Charpentier, 1841.1.

(40) Agassiz, 1837.1; 1840.1; 1840.2.

(41) Morlot, 1854.1.

(42) Chamberlin, 1895.1; 1905.1, vol. III, chap. XIX, pp. 327-516.

(43) Salisbury, 1905.1.

(44) Penck, 1909. 1,

(45) Leverett, 1910.1.

(46) Lyell, 1867.1, voL I, pp. 293-301; 1877.1, vol. I, p. 287.

(47) Dana, 1875.1, p. 591.

(48) Walcott, 1893.1.

(49) Upham, 1893.1, p. 217.

(50) Heim, 1893.1.

(51) Sollas, 1900.1.

(52) Penck, 1909.1, vol.III, pp. 1153-1176.

(53) Geikie, 1914.1, p. 302.

(54) Reeds, 19 1 5. 1.

(55) Nüesch, 1902.1.

(56) Geikie, op. cit. pp. 111-114.

(57) Op. cit., p. 108.

(58) Huntington, 1907. 1.

(59) Leverett, 1910.1.

(60) Obermaier, 1912.1, p. 132.

(61) Penck, 1908.1; 1909. 1.

(62) Geikie, 1914.1, p. 312.

(63) Wiegers, 1913.1.

(64) Boule, 1888. 1.

(65) Schuchardt, 1913.1, p. 144.

(66) Obermaier, 1909.2; 1912.1.

(67) Schmidt, 1912. i, p. 266.

(68) Penck, 1909. i, vol III, p. 116S, Fig. 136.

(69) Neumayr, 1890.1, vol. II, p. 621.

(70) Martins, 1847.1, pp. 941, 942.

(71) Osborn, 1910.1, pp. 386-427.

¶ Footnotes

Lucretius was born 95 B. C. His poem was completed before 53 B. C. In the opening lines of Book III he attributes all his philosophy and science to the Greeks. See Appendix, Note I. ↩︎

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, metrical version by J. M. Good. Bohn’s Classical Library, London, 1890. ↩︎

Horace was born 65 B. C., and his Satires are attributed to the years 35-29 B. C. See Appendix, Note II. ↩︎

AEschylus was born 525 B. C. See Appendix, Note III. ↩︎

Georges Louis Leclerc Bullon (b. 1707, d. 1788). For reviews of Buffon’s opinions and theories see Osborn, 1S94.1, pp. 130–9; also Butler, 1911.1, pp. 74-172. ↩︎

Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, known as the Chevalier de Lamarck (b. 1744, d. 1S29). For a summary of the’Hews of Lamarck see Osborn, 1894.1, pp. 152181; also Butler, 1911.1, pp. 235-314, ah excellent presentation of Lamarck’s opinions. ↩︎