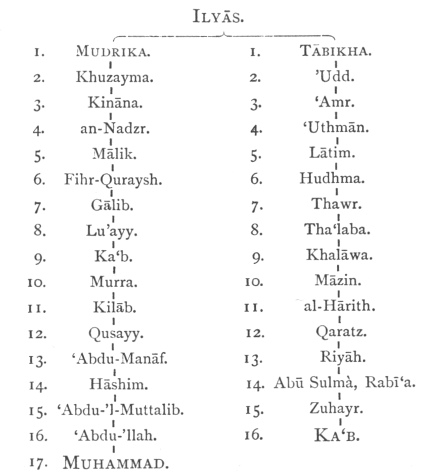

Preface, p. 307, l. 1-10.—Ka‘b, the Poet, and Muhammad, the Lawgiver, were descended, by sixteen and seventeen degrees respectively (not seventeen and fifteen, as stated in the Preface), from Ilyās, the son of Mudhar, the son of Nizār, the son of ‘Adnān; as is shown in the subjoined genealogies, both from An-Nawawī’s “Biographical Dictionary,” edited by Wüstenfeld: Göttingen, 1842-47. That of Muhammad is identical with what is found in p. 1, text, of “The Life of Muhammed” of Ibn Hishām, by the same editor; London, 1867. The transliterations are by the translator. Sir W. Jones, in his “Genealogy of the Seven Arabian Poets,” puts “Mozeinah” (read, Muzayna) in the place of ‘Amr, as No. 3, in the descent of Zuhayr, the father of Ka‘b. Muzayna may have been a surname of ‘Amr, as Abū Sulmà was that of Rabī‘a.

[ p. 460 ]

Sir W. Jones adds a name, “‘Awàmer,” between Qaratz and Riyāh—by him written “Kerth” and “Reiáhh”—but Nawawī has it not.

Ilyās.

| 1. Mudrika. | 1. Tābikha. |

| 2. Khuzayma. | 2. ’Udd. |

| 3. Kināna. | 3. ‘Amr. |

| 4. an-Nadzr. | 4. ‘Uthmān. |

| 5. Mālik. | 5. Lātim. |

| 6. Fihr-Quraysh. | 6. Hudhma. |

| 7. Gālib. | 7. Thawr. |

| 8. Lu’ayy. | 8. Tha‘laba. |

| 9. Ka‘b. | 9. Khalāwa. |

| 10. Murra. | 10. Māzin. |

| 11. Kilāb | 11. al-Hārith. |

| 12. Qusayy. | 12. Qaratz. |

| 13. ‘Abdu-Manāf. | 13. Riyāh. |

| 14. Hāshim. | 14. Abū Sulmà, Rabī‘a. |

| 15. ‘Abdu-’l Muttalib. | 15. Zuhayr. |

| 16. ‘Abdu-’llah. | 16. Ka‘b. |

17. Muhammad.

l. 11. The orthography “Abu-Solma” is erroneous—a result of the Hebraizing proclivities of early European Arabists.

v. 1. The name Beatrice is a fair equivalent to the Arabian original Su‘ād (i.e. happy), and conveys a more definite impression to the English reader.

v. 10. “Promises of ‘Urqūb” is an Arabian proverb, about equivalent to our “Fudge.”

v. 20. From the genealogy of the Poet’s camel we are to understand that there were two brothers and a sister: one of the [461] brothers, himself got out of the sister, gets the filly out of her also;—he is thus father and brother; the other brother is paternal and maternal uncle.

v. 25. This verse is very obscure in the original, and has many variants. It seems to intimate that the Poet’s imaginary camel had never foaled, had never had a full udder, had never been sucked or milked. The best commentary consulted explains that the “whisking” is to drive away flies.

v. 29. The rocks are supposed to be so hot that a “piebald locust” cannot bear them: he touches them with his feet, and withdraws; but he is tired also; so he again tries to alight, and is again and again repelled by the hot rock.

v. 31. The Poet’s mother is pictured as beating her breast with her two hands alternately, tearing her flesh and her clothes, on hearing that the Prophet had doomed her elder son, whose enemies derived pleasure in tormenting her with assurances that he is already as good as dead. The other “bereaved ones” are probably mothers of warriors killed in the recent wars against Muhammad.

v. 34. The Poet here, by a poetical amplification, calls himself the son of his grandfather, or, by a contraction, omits his father’s name. All Israelites are “Sons of Abraham.”

v. 35. Here he recounts how he was refused protection by an old friend; and how (v. 36) he resolved to appeal to the Prophet himself, saying (v. 37) that, “after all, a man can die but once.”

v. 38. This verse is held to be “the verse of the Poem”—that is, it recites the pith of the reason why the Poem was composed: “pardon is hoped for from the Apostle of God.” Twice does the Poet, in this verse, skilfully use the expression, “Apostle of God,” thereby reminding the Prophet of his conversion to Islām.

v. 41. Muhammad was born in the year when Abraha, viceroy of Arabia Felix for the King of Ethiopia, advanced against Makka with an elephant in his train, to destroy the sacred temple of the pagan city, he and his sovereign being Christians. Arrived in front of the city, the elephant refused [462] to obey his leader and advance to the attack. Abraha was obliged to withdraw, and his army perished in a way very variously explained. The elephant of Abraha is said to have seen and heard an angel threatening him, should he advance; but Ka‘b was deterred by no dissuasions, for who was more terrible than the incensed Apostle, whose pardon was hoped for?

v. 51. The Qur’ān styles Muhammad “a Light from God.”

v. 52. The “small band of Quraysh” were those who had abandoned Makka and migrated to Madīna for the faith. Their “spokesman,” who commanded them to depart, was Muhammad himself.

v. 55. By “shirts of the tissue of David” is meant coats of mail; for tradition asserts that David was divinely taught, and was very skilful in the manufacture of link armour.

Muhammad subsequently objected to Ka‘b that his Poem had in it not one word of praise for the “auxiliaries” of Madīna, whereas they were in every way worthy of eulogy, and had felt hurt by being excluded from his panegyric of the “emigrants.” Thereupon the Poet indited in their special honour a series of verses, and praised them for the fidelity with which they had carried out their promise to assist the Prophet to the death, and the steadfastness they had shown on many a trying occasion on his behalf.