[ p. 214 ]

When Yunus fled into the laden ship; and

Those who were on board cast lots among

Themselves, and he was condemned; and the

Fish swallowed him. . . . And We cast him

On the naked shore, and he was sick; and We

Caused a plant of a gourd to grow up over him.

The Koran.

HALF-WAY across the Lut was a land of moving sands known as the “Sand of the Camels”; and here we endured much trouble, as we had only been able to hire donkeys at Saghand, and owing to the heat and the absence of water, we all suffered terribly. Indeed several of the pilgrims, most of whom were half-naked and on foot, fell down and remained senseless until the evening; but, praise be to Allah, they finally reached the stage where, although the water was salt, they all drank to repletion, so much so that the caravan had to halt for two days, as every one was ill, owing to the heat, thirst, fatigue, [215] and, above all, the salt water. Yet we were very thankful that there had not been a storm, as many a caravan has lost its way and all its members have perished when the wind has moved the sands and covered up the track.

We were now in Khorasan, the Land of the Sun, and as it is one of the great provinces of Iran, it is advisable for me to briefly describe it. Khorasan stretches from the extreme north-east of Persia down to the province of Sistan, which is included in the same government, and which was the home of Rustam, the mighty champion of Iran.

Among the famous cities of the province are Tus, built by one of the generals of Kei Khusru and Nishapur, founded by the Sasanian monarch Shapur. To-day, however, owing to the Shrine of the Imam Riza, Peace be on Him, Meshed is the capital of this vast province.

I have read in the Shah Nama that it was at Kishmar, in the district of Turshiz, that Zoroaster planted a cypress, brought by him from Paradise, to commemorate the conversion to the new faith of Gushtasp, the Shah. For many centuries this cypress increased in size, until, fourteen hundred and fifty years after it was planted, the Caliph Mutawakkil ordered it to be felled and to be transported to Samara on the Tigris, where he was building a new palace.

[ p. 216 ]

The hapless Gabrs offered large sums of money in vain, and the tree was cut down, but the night before it reached its destination the Caliph was murdered by his son. I mention this story to show how very ancient and glorious a province Khorasan is, as it is now more than a thousand years since the death of Mutawakkil.

Khorasan, indeed, has many wonderful places. Among them is the fort of Kalat-i-Nadiri, which was undoubtedly built by the Divs, as it consists of a valley surrounded by hills which only a bird can cross, so precipitous are they.

In it Nadir Shah collected all the jewels and gold which he brought back from India, where his victorious army reduced its monarch to be his servant. This fortress, which is only defended at the five closed entrances, is one of the marvels of the world, and not even Amir Timur could capture it, as none of his soldiers could fly; and we Iranis may sleep in security so long as Bam in the south and Kalat-i-Nadiri in the north are garrisoned by the ever-wakeful troops of the mighty Shah, whose honour and glory are increased by the possession of these two great fortresses, which are famous throughout the Seven Climates.

As to the people of Khorasan I cannot entirely praise them, indeed they are noted throughout Iran for being dull and stupid; but then [217] every one agrees that it is the Kermanis and Shirazis who are the cleverest and wittiest people in Persia, whereas in the north there are too many Turks, who are slow and dull.

To prove this stupidity of the Khorasanis, there is the story of three Persians who were each praising their own provinces. The Kermani said, “Kerman produces fruit of seven colours”; the Shirazi continued, “The water of Ruknabad issues from the rock”; but the poor Khorasani could only say, “From Khorasan come fools like myself.”

However, I think that the Khorasanis, if dull, are very honest and very hospitable; and during my stay in their province I always found them most polite, and, as the poet says:

Whomsoever thou seest in the saintly garb,

Suppose him to be a good man and a Saint.

After traversing the terrible Lut, where we had suffered not only from the difficulties and dangers of the road, but also from the savageness of man, Tabas, the gate of Khorasan, as it is well named, appeared to us as beautiful as Damascus did to the Prophet. May the Peace of Allah be on Him and on His family!

In truth, when we rode up an avenue bordered on both sides by mulberries, elms, willows, and palms, and saw the streams of running water, we thanked Allah the Bountiful that we had, at [218] last, arrived safely in an inhabited country after all our sufferings.

Tabas is termed Tabas of the Date Palm, to distinguish it from Tabas of the Jujube Tree in the district of Kain. It has always been famous not only for its dates and oranges, but also for its heat. Indeed, in Khorasan, to say “Go to Tabas” is not a polite remark.

Many centuries ago it was in the hands of the Ismailis, who, under Hasan Sabbah, seized the district. Now there is a legend to the effect that the Nizam-ul-Mulk, the famous Vizier, was a school-fellow of both Omar Khayyam and Hasan Sabbah; and the three youths bound themselves by an oath, sealed with blood, that whichever among them became powerful, would aid the other two.

When the Nizam-ul-Mulk rose to be Vizier, he offered Omar Khayyam the governorship of Nishapur: but the philosopher wisely declined, and, instead, asked for a pension, which was granted to him.

Hasan Sabbah, who was ambitious, asked for a post at Court, and there intrigued against his benefactor. He was, however, found out and fled to Egypt, whence he, later on, returned to Persia, where he founded his famous sect of disciples.

It is stated that the devotees of the sect were [219] given hemp, and when under its baleful influence were carried into a terrestrial paradise with beauteous houris, gardens, running streams, and all other delights. After enjoying these pleasures for three days, they were again drugged and carried out; and thenceforward believed that, if they executed the orders of Hasan Sabbah, they would return and remain for ever in this paradise.

To give a single example of how they acted, I would refer to the case of Ibn Attash, who established a branch of the sect at Isfahan, and so successful was he that his followers increased in numbers most rapidly.

Just about this time numerous inhabitants of Isfahan began to disappear in a most mysterious manner, and Allah the All-wise used a poor beggar woman as the instrument whereby this wickedness was revealed. For she asked for alms at a certain house whence she heard groans proceeding; but when invited to enter she exclaimed, “May Allah heal your sick,” and fled to rouse the quarter.

When the mob broke open the door they beheld some four or five hundred victims, many already dead; but a few, who had been recently crucified, were still alive. May the pity of Allah be on them!

This place of slaughter belonged to a blind [220] man, who used to stand at the end of the long lane leading to his house crying, “May Allah pardon him who will lead this poor blind man to the door of his dwelling!” There the Ismailis seized and tortured the unsuspecting victim, who was done to death in return for a good deed. May the curse of Allah be on Hasan Sabbah and on his Sect!

Alhamdulillah! to-day the remnants of this sect, who still inhabit Kain and Nishapur, have left this path of darkness; and by the good fortune of His Auspicious Majesty, are simple villagers engaged in cultivating their land and praying for the long life of the Shah.

We presented ourselves before the Governor, an old man, who claimed descent from Nadir Shah. It is also said that his family has rendered such help to the Kajar dynasty that it will always keep the government of Tabas. His Excellency showed us kindness, and on hearing what had occurred he was very angry, and swore that he would burn Gholam Ali’s father. [^61] He immediately sent a body of his brave sowars, who finally captured the robber and brought him bound on his horse to Tabas; but just before he was imprisoned in the fort, he broke away bound as he was, and galloping his horse, [221] took sanctuary in the shrine of Shahzada Sultan Husein. There, as you, O readers, probably do not know, he was safe so long as he remained within the sanctuary, and I have heard nothing since that day as to what happened.

In any case none of our stolen money or property was restored to us, although the Governor treated me with much kindness and gave me one hundred tomans, when we called to request permission to depart and to continue our journey.

For some stages we crossed a boundless salt desert, and in the middle of it was Yunusi. This village is famous all over the world, as it was here that the whale cast up the Prophet Yunus, [^62] on him be Peace! In those days, as I have already mentioned, the salt swamp was a great sea, and, consequently, there is no doubt that this was the very spot where the Prophet reached the shore, and where a gourd grew and formed a shelter of greenery over his senseless frame. Truly Allah is great!

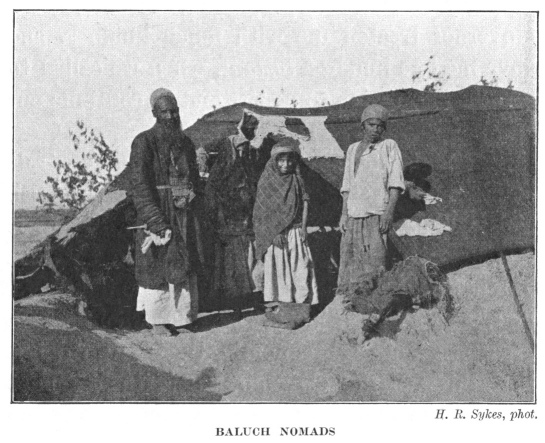

Two stages after leaving Yunusi we passed several encampments of Baluchis, who weave good carpets, and reached Mahavalat, noted for its melons, which, like many things in Persia, are unsurpassed. So delicate are they that they cannot be grown near a road, as the gallop of a [222] passing horse would split them; and, alas! for the pleasure of the world, they cannot be carried even as far as Meshed, so tender are they; and yet so luscious and sweet that how can I represent it?

However, Mahavalat was not a stage of good omen as, at it, there was nearly spilling of blood, which Allah forbid for men bound on a pilgrimage to the threshold of the holy Imam.

H. R. Sykes, phot.

It happened in this wise. Ever since we had been robbed at Rizab, Mohamed Riza Khan, the son of Assad Ullah Khan, had every day by hints and insinuations cast reflections on the courage of the Kermanis in the presence of Ali [ p. 223 ] Khan; moreover, he said that, had one of his grooms been watching instead of the two servants of Mahmud Khan, the calamity would never have befallen us. In short, there was ill-feeling between these two hot-headed youths.

On this occasion, Ali Khan said to Mohamed Riza Khan, "If you grant me permission, I will tell you how in Kerman we have knowledge of the bravery of the men of Fars. Some years ago, Isfandiar Khan, Buchakchi, the chief of one of our small tribes, entered Lar with about twenty of his fellow-tribesmen, and stated that he had the orders of His Auspicious Majesty to collect the revenue. The men of Lar at first swore that they would resist, but when Isfandiar Khan ordered his Mirza to write a telegram to the ‘Foot of the Throne,’ to the effect that the Laris were rebellious, they at once ate dirt and paid the revenue to the crafty brigand, so that when the Governor-General of Fars sent his servants to levy the taxes, behold Lar was as naked as the Lut, for Isfandiar Khan had clean eaten it up.

“Well, the Governor-General came with a large force to capture Isfandiar Khan, who, at first, sent polite messages to His Excellency; but, at length, he grew tired of being pursued like a fox, and said openly that there would soon be a ‘Night of blood.’

[ p. 224 ]

“The Shirazis heard this, and that night the brave Governor-General had a deep hole dug in his tent in which to hide under the felts should an attack be made. However, nothing happened until six hours of the night had passed, when the Shirazis heard the thundering of horses’ hoofs and thought that the Day of Judgment had come. Immediately they all fled, crying Aman, or quarter; but the thunder of hoofs came ever nearer, and, at last, it was seen that the lionhearted Shirazis were fleeing from a herd of mares which had been attracted by the camp fires.”

As Ali Khan finished this story, Mohamed Riza Khan leaped at him like a leopard, and had not Mahmud Khan and I hastened to the spot, Allah knows what would have happened. As the Arab proverb runs, “Jesting is the forerunner of evil.”

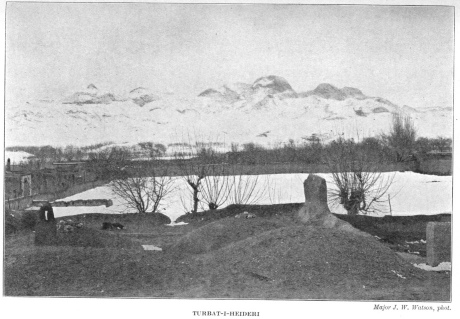

After quitting Mahavalat, we rode on hour by hour until at sunset we reached Turbat-i-Heidari, so termed after the saint known as the “Pole of Religion.” Holy indeed was he who, alone of mortal men, clothed himself in felt in summer, and passed frequently through fires, and who, to still further mortify his body, slept without any covering in the “Forty days of Cold.” In short, “The Chosen of Allah are not Allah, but they are not separate from Allah.”

[ p. 225 ]

Major J. W. Watson, phot.

[ p. 226 ]

[ p. 227 ]

Upon our arrival at Sharifabad, which you should know is but one stage from Meshed the Holy, we found all the rooms in the caravanserai and houses already occupied by pilgrims from Tehran. Indeed, we had almost lost hope of finding any accommodation, so great was the throng, when we were met by a handsomely clad Sayyid, who accosted us in a very friendly manner with “Welcome, Khans of Kerman, you need be under no apprehension about your quarters, as they are ready.”

Needless to say, we were very much gratified to see that our reputation had preceded us even to this distant part of the country, and followed our guide to a small house with a garden which appeared most delightful to us after nearly two months of travel.

We quitted Sharifabad early in the morning, and even our very horses seemed to go faster, as if they felt that this was the last stage to Meshed the Holy. We crossed green, rounded hills, and at last one of our chief desires was fulfilled, for we had reached the highest ridge, known as the “Hill of Salutation”; and the golden dome of Meshed, the Glory of the Shia World, lay before us.

In the centre of the fertile valley of the Kashaf Rud we could see the Holy City surrounded by green gardens resembling emeralds, [228] out of which rose the ineffable sheen of the unsurpassed dome with its peerless golden minarets; in truth so bright was its glory that we could not continue to gaze on it.

Meanwhile, the Sayyid spread a handkerchief and began to recite a prayer which we repeated after him, “Peace be on you, the members of the Prophet’s family, the Seat of the Messenger of Allah, the Centre of the Angels, the Abode of the Angel Gabriel, the Mine of the blessings of Allah, the Guardians of Knowledge . . . . Peace be on Thee, O the greatest Stranger of all the Strangers, [1] the Sympathiser of the souls, the Sun of the Suns, buried in the soil of Tus.” We then all shook hands and threw money into the handkerchief, and as I saw Assad Ullah Khan give a two kran piece, I threw down a piece of gold just to teach him that it was not the time to be parsimonious.

There were seven or eight other parties of pilgrims like ourselves on the hill. Amongst them was a merchant from Yezd, who was beaming with happiness and shaking hands and receiving congratulations. We were informed that his wife, faithful to her vow, that if her husband took her to the Sacred Shrine she would forego her dowry rights to a large landed [229] estate, had transferred her claim to her husband. Indeed, it is a common act of piety with ladies, who after a life of longing have prevailed upon their husbands to bring them to Meshed, to forego their claim to their dowries on catching the first glimpse of the Holy Shrine.

Hundreds of returning pilgrims too tarried on the hill to say their last prayer with the golden dome in view, and to pile up stones as a remembrance. It is customary for all such parties to say “We petition for prayers,” and thus to beseech pilgrims going to the Shrine to pray for them there. In reply, the hope is expressed that their pilgrimage has been accepted.

On reaching Turuk, one and a half farsakhs from Meshed, we drank a cup or two of tea and then entered carriages provided by our friend the Sayyid. Between Turuk and the Holy City we saw some huge rocks, whose weight Allah alone knows; and Sayyid Mirza Ali stopped the carriage, and pointing to their rounded shape, explained to us that these inanimate objects were like ourselves, bound from distant regions to kiss the threshold of His Highness the Imam.

As Ali Khan, who is, you must know, merely a youth, looked as if he doubted this fact, the Sayyid said to him, “O brother, thou shouldest [230] build thy house of belief on the foundations of faith, otherwise thy house will fall.” He then asked us if we had not heard of what happened to the Prophet Musa, on him be peace! who in a like case was tempted to belittle faith.

By the orders of Allah he visited a hermit, and found the holy man deep in prayer and rubbing his face on the ground. He explained to the Prophet that by such works alone could salvation be secured.

The Prophet, inspired by Allah, asked the hermit whether it were possible to pass one’s finger through the eye of a needle; but the hermit rebuked him sternly for asking such a foolish question.

The Prophet then visited a second hermit whom he found in tears. Upon inquiry, the holy man said that he hoped, by humility and faith, to secure salvation, but not by works. Again the Prophet put the same question; and again he was rebuked, but this time for doubting the power of Allah, who could pass a camel or an elephant, or the whole eighteen thousand worlds, through the eye of an ant, which is much smaller than that of a needle.

The Sayyid ended his homily with the following verse:

Do not think that thou art pleasing the King by serving him; but be thankful that he has accepted thee as a servant.

[ p. 231 ]

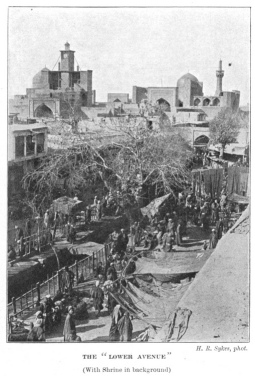

(With Shrine in background)

H. R. Sykes, phot.

[ p. 232 ]

[ p. 233 ]

To this Ali Khan made no reply, and you, O readers of London and of the New World, revere our ancient faith, and do not forget that it is only the Moslems, the Christians, and the Jews who are People of the Book.

Upon approaching the Holy City we saw mighty walls with massive towers, and crossing a handsome stone bridge we entered the “Lower Avenue” gate. The “Avenue” of Meshed is so famous for its crystal stream, its superb plane trees, and its great width, that I need not mention its perfections; but one thing I must state, which is that, even on the Day of Judgment, it would be difficult to see a much greater assembly of Mussulmans from the Seven Climates than I saw. To give a list would be impossible.

We were driven to a house in the “Upper Avenue,” which was to be our residence in the city, and there partook of breakfast. After this we composed ourselves to sleep, and on waking found our mules had arrived.

With haste our servants opened our boxes and took out new suits of clothes which we had purchased in Tabas. We then proceeded to the hammam and, thoroughly refreshed, we gave our travelling clothes to the attendants, and were at last ready to cross the Sacred Threshold.

¶ Footnotes

220:1 “To burn a man’s father” in Persia is the most usual threat. A burnt Mohamedan has no chance of Paradise. ↩︎