| Chapter XI. Yezd, the Prison of Alexander | Title page | Chapter XIII. The Arrival at the Sacred Threshold |

[ p. 191 ]

Therefore we delivered Lot and his family,

Except his wife; she was one of those

Who stayed behind: and we rained

A shower of stones upon them . . . and

We turned those cities upside down.

The Koran.

We had reached Yezd on the sixth day of the sacred month of Muharram; and this we had purposely intended, as, being pilgrims, we were especially bound to take part in this sad anniversary. In a previous chapter I referred very briefly to the difference between us Shias and the Sunnis. I will now give further details, as, indeed, I then promised.

We know that when, for the last time, Mohamed, on Him and on his family be Peace! performed the pilgrimage, known as the Farewell Pilgrimage, the angel Gabriel came to him at Mecca, with instructions from Allah, the [ p. 192 ] All-Wise, to proclaim publicly that Ali should be his successor.

Upon the conclusion of the pilgrimage the Prophet, accompanied by Ali and his other companions, started on his return journey, and, at a village termed Khumm, close by which there was a pool of water, the solemn investiture was held. A throne, constructed of camel saddles, was erected, and Ali was set thereon by the Prophet, who then embraced the “Lion of Allah” in such a close and long embrace that, by this act, his virtues were transmitted to his illustrious son-in-law. Finally, the Prophet formally constituted Ali as his successor and heir; and this historical event is annually celebrated with much rejoicing under the name of “the Festival of the Pool of Khumm,” wherever Persians reside.

However, owing to the wickedness of mankind, Abu Bekr, Omar and Osman were all elected Caliphs before Ali came to his right, and he only ruled for a few short years, being foully murdered in the sixth year of his Caliphate. After his death, his eldest son, Hasan the Pious, succeeded him; but being wearied with the faithlessness of the Arabs, he abdicated, and, like his descendant the Imam Riza, was poisoned.

Ten years later his brother Husein, who had been promised the succession to the Caliphate [193] upon the death of Muavia, was invited by the fickle Kufans to trust himself to their support to win the throne which was justly his, and, accompanied by a small band of his faithful followers and his family, he started off on this ill-omened journey.

Upon his approach the Kufans, the curse of Allah be on them! deserted the cause of the Imam, who declined to retire but resolved to die fighting to the bitter end, being fortified in this resolution by the vision of a phantom horseman who said to him, “Men travel by night, and by night their destinies travel towards them.”

He encamped with his small party at a place called Kerbela, near the bank of the Euphrates, and, to ensure a desperate defence, ordered the tents to be fastened together, to prevent an attack from that quarter.

In the morning both sides prepared for battle, the forces of the enemy being under Umar bin Saad, who was bribed to oppose the Imam by the promise of the governorship of Rei. He himself wrote the following verse on the subject:—

Shall I govern Rei, the object of my desire?

Shall I be accursed for slaying Husein?

The murder of Husein damns me to inevitable flames:

Yet sweet is the Possession of Rei.

Umar’s force numbered four thousand, whereas the band of the Imam consisted of but [194] seventy-two devoted followers. However, before the battle commenced, Al Hurr, an Arab chief, who commanded thirty horsemen, quitted the ranks of the enemy and joined the sacred force with his son, brother and slave, the other sowars declining to follow him. By Allah! we reverence his memory even to-day and remember how he reproached the Arabs in these words: “Alas for you! you invited him and he came, and you not only deceived him, but are now come out to fight against him. Nay, you have hindered him and his wives and his family from the waters of the Euphrates, where Jews and Christians and Sabæans drink, and where pigs and dogs disport themselves.”

When the battle commenced two warriors stepped forth from the ranks of the enemy, but they and many other champions were slain by the indomitable heroes, until Umar withdrew his horsemen and sent five hundred archers to the front, who rained in arrows. Even then the warriors of the Imam were unconquered until, after the fight had raged the whole day, and the entire party of the Imam had been slain, the Imam himself, overpowered by countless wounds, fell in a last desperate rush among the foemen. May the Peace of Allah be on him, and His forgiveness be on the members of his band and on Al Hurr!

[ p. 195 ]

[ p. 196 ]

[ p. 197 ]

The helpless women were stripped and insulted by their captors and also by the pitiless rabble on the way to Damascus, where the accursed Yezid, son of Muavia, endeavoured to aggravate their sorrows in such a fashion that it can never be forgotten.

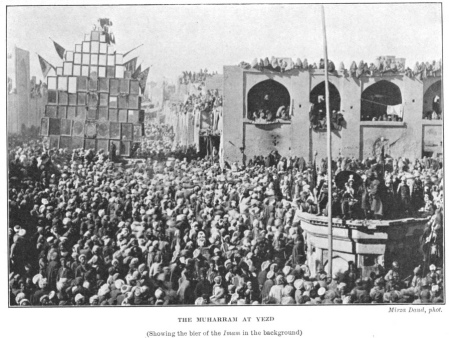

It is this awful tragedy that we Shias celebrate in the month of Muharram, and on the tenth day, the anniversary of the murder of the Imam Husein, the Prince of Martyrs, there are always processions to remind us of the heart-rending calamity. In Yezd each of the seventeen quarters prepares a procession, the cost of which is partly defrayed by the legacies of pious men.

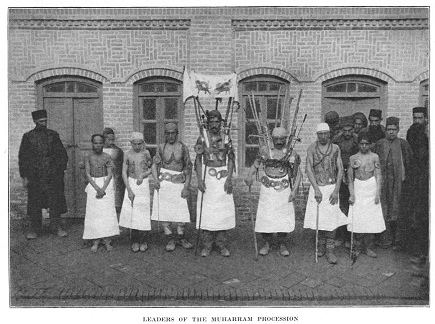

The procession I joined was headed by a band of men who, to honour the Imam by self-inflicted pain, had hung horse-shoes, locks, and heavy chains to their bare bodies, and who, by their example, encouraged even little children to wound themselves in memory of the wounds of the Imam.

Then came camels laden with tents, and innumerable mules, lent by their pious owners, carrying baggage, followed by a hundred horses with shawls draped on their necks and by two hundred led horses. Behind these there were thirty-five camels, ridden by members of the Imam’s family, representations of the seventy-two [198] bodies of the martyrs, seventeen heads on lances and a band of Arab horsemen. Two singers of war songs represented the two parties and engaged in a heated dialogue, mingled with curses.

Then came Hazrat Abbas, the standard-bearer, accompanied by eighty water-carriers. It was he who was slain when attempting to draw water from the Euphrates.

Among the most conspicuous features was a wooden house draped in black to represent the bridal chamber of Fatima, daughter of the Imam, who was married to her cousin Kasim just before the fatal day. A hundred dervishes with their axes, horns, and lion or leopard skins also formed part of the procession.

The next scene was that of Yezid on his throne, surrounded by his Court, while eighty men beat two stones together and recited mournful verses. Nor must we forget the ambassador from Europe, who, seeing Yezid insult the head of the dead Imam, fearlessly rebuked him before all his courtiers. Finally, there was a model of the tomb of the Imam, surrounded by brave officers and soldiers of the ever-victorious army of Iran.

In the different parts of the procession groups of two hundred men beat their breasts in rhythm, and as they advanced they recited:

[ p. 199 ]

(Showing the bier of the Imam in the background)

Mirza Daud, phot.

[ p. 200 ]

[ p. 201 ]

O our Imam Jafar! [^55]

Husein our Lord

Has been murdered on the plain of Kerbela;

Dust be on our heads.

And so the procession moved in stately order to the square of Mir Chakmak, where there is an octagonal, tile-covered pillar, which is peculiar to Yezd. There a halt was made, while an enormous structure, representing the bier of the Imam, decorated with fine Kerman shawls and innumerable flags, mirrors, swords, and daggers, was slowly carried round the Square by five hundred men, who bore this heavy burden as a sacred privilege. It is the pride of the inhabitants of the village of Mohamedabad to render this unique service to the Imam; and nowhere else in Persia is there such a huge bier. From the Square the procession proceeded to the Palace, where the Governor loaded its organisers with gifts and released two prisoners convicted of murder; and so back to its quarter, after having shown to men, women, and children the poignant tragedy of Kerbela, which will not be forgotten by us Iranis until the Day of Judgment.

After taking part in the procession on the tenth of Moharram, we decided to continue our [202] journey across the dreadful Lut to Tabas without undue delay. As I am deeply versed in geography, and am not among those who believe that “Atlantic” is the name of a city, perhaps the people of London would like to hear from me about our famous desert, for, just as the gardens of Iran surpass all others for beauty, so the Lut, well named after one of our prophets, Lut or Lot, on Him be Peace! surpasses all other deserts in the world for its extent and aridity.

Now the Lut stretches from near Tehran across the centre of Persia to the frontiers of Baluchistan, a distance of two hundred farsakhs, and, if travellers speak the truth, this desert really stretches almost to India; but only in Iran is it called the Lut. From north to south its extent is nowhere more than one hundred farsakhs wide, and, by the road we were travelling, it scarcely exceeds fifty farsakhs in width.

This huge desert was once, according to our histories, a sea; but nowadays there are great ranges without water and vast areas of moving sand, which covers the road if there be a strong wind. Again, there are huge salt swamps, more especially in the northern portion, and elsewhere it is so stony that it is necessary to travel very slowly. Throughout there is very little water, and generally it is salt. Indeed, there are countless [203] steep passes over the ever-barring ranges of hills, fearful ascents and descents, dangerous swamps, and the terror of the moving sands. The climate is either extremely hot or bitterly cold. Indeed only a brave and hardy race like we Iranis would dare to cross such an awesome place, which is not only haunted by Ghouls and Afrits, but also by robbers with savage faces and evil hearts.

There is no water, no habitation, and

No summons to prayers of the Mussulman.

In all this huge waterless tract there is unlimited grazing for camels, but little else. I have read that the camel-bird [^56] in ancient days inhabited this desert, and the Doctor Sahib told me that the English in Africa now make much profit from selling its feathers. In the name of Allah, then, let them come and show us Persians how to become rich from our boundless Lut!

We resumed our journey on a propitious day; but, just as I was mounting, Ali Khan sneezed violently, and had not Mahmud Khan, who declined to pay an extra day’s hire for the mules, prevented us, we should not have started that day. Allah knows how true is our proverb, “Greediness makes a man blind.”

About a farsakh from Yezd we dismounted [204] to smoke a water pipe, and, sitting on a ridge overlooking the city, we swore with an oath that it was not fit for any one to live in but the Yezdis. As Ali Khan truly remarked, the city was composed mainly of wind-towers. [1]

We rode slowly forward, and as we were descending a little valley, a hare suddenly crossed our track to the left. Mahmud Khan turned white like curds at this evil omen; but, angry at his behaviour in the morning, I pointed out that what fate ordained would be; and that avarice was composed of three letters, and that all three were empty. [2]

In truth, I could not content myself with this proverb, but said to them, “Have you not heard the story about the late Commander-in-Chief of the Persian army at Tabriz?” This personage was so avaricious that he used to allow the regiments on duty to return to their homes only if their officers paid him large sums of money.

This was his constant habit, until he was very ill and the Angel of Death was knocking at the gate, when he was told that General Najaf Ali Khan had come to see him about dismissing the [ p. 205 ] Muzaffari regiment; but that, as he was ill, he would not be allowed to trouble him.

Unable to speak, the dying man gave a sign that the petitioner should be admitted; and the General, after a few words, offered one thousand tomans. The Commander-in-Chief was in the death agony; but, just before the Angel of Death seized his soul, he shook two lean fingers at the General, signifying thereby that he must pay two thousand tomans, and, shaking his two fingers, he died. Truly Allah is great and his paths are hidden!

To complete my ill-humour, when we halted to eat our breakfast my servant Gholam Riza represented to me that my samovar had evidently been stolen at Yezd, as he could not find it in the morning when packing up. He added that this was fate. This answer made me so angry that I exclaimed, “Thou half-boiled jackass, dost thou not know what our Prophet, on him and on his family be Peace, replied to such a one as thou?” He ordered: “Tie up the knee of thy camel, with thy trust in Allah.” Better advice than this has no man given.

The following day the head muleteer suggested to us to ride about a farsakh to the left of the track, as we should see the famous City of Lut. And indeed it was a wonderful spectacle, as, on each side of a wide valley we saw the ruins of [206] great forts and of wonderful buildings, so enormous and so magnificent that they must have been built by the Divs. Here then was the country which Allah the Omnipotent destroyed, as it is written in the Koran, “We turned those cities upside down.” O my brethren, tremble and fear the vengeance of Allah the Omnipotent! and forget not the awful punishment that fell on those evil-doers.

That night at Kharana we overtook a caravan of pilgrims from Shiraz, who had been delayed for a week by rumours that a band of robbers was holding the road. However, the arrival of our party, sixty strong, doubled our numbers; and it was decided to march together until Meshed was reached.

In the caravan from Shiraz were two Khans with whom we made acquaintance. But it must be stated clearly that, in the whole of Persia, there are no people so immoderately proud of themselves as the Shirazis. Indeed, before we had been together an hour, the son of Assad Ullah Khan quoted from Shaykh Sadi:

Judge with thine eyes and set thy foot in the garden fair and free,And tread the jessamine under foot, and the flowers of the Judas tree.O joyous and gay is the New Year’s Day, and in Shiraz most of all,Even the stranger forgets his home and becomes its willing thrall. [ p. 207 ] Fortunately, I was as well acquainted with the great poet’s works as the Khan, and I stopped this boasting for a while by quoting:

My soul is weary of Shiraz, utterly sick and sad;

If you seek for news of my doings, you will have to ask at Baghdad.

However, it was no use as, whatever we said, our companions could not realise that it was their good fortune at having two such poets as Shaykh Sadi and Khoja Hafiz born at Shiraz that had made their city known, whereas actually its climate is damp and unwholesome compared with Kerman, and in size there is no comparison. To say more would be excessive.

The morning we left Kharana it was arranged that we Khans with our armed servants should ride in front of the caravan in order to protect it; and we warned all the pilgrims not to straggle. No one would, however, pay attention to our warning, and the Chaoush, [3] who was reading suitable passages from the Koran, to which every one replied by Salawat or “Blessings,” said that we should not be troubled, as His Highness the Imam Riza would protect his servants.

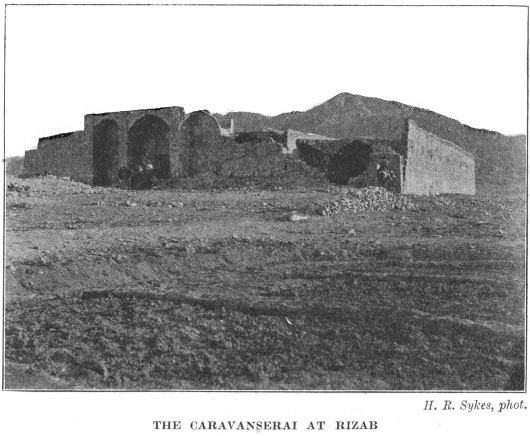

We stopped for the heat of the day at Rizab, a dilapidated, sinister-looking caravanserai. We knew that this was a dangerous place, as we had [208] been informed that robbers from Fars had been heard of quite recently in the vicinity; but, to our delight, we found the place empty, and, feeling much relieved, we ate our breakfast with relish.

Mahmud Khan ordered two of his servants, as a precaution, to keep watch, and we all composed ourselves to sleep about noon. Just as we thought it was time to arouse ourselves and finish the stage, a terrible uproar occurred, and, before we had time even to seize our rifles, we were captured by the Fars robbers.

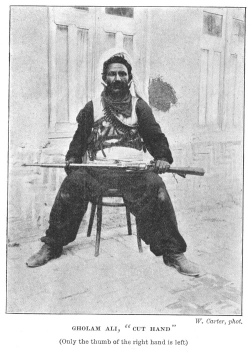

Their leader, Gholam Ali, was a man of most ferocious aspect, and when he recognised Assad Ullah Khan, he glared at him like a Div. Assad Ullah Khan was frozen to the spot like a statue; and it was explained that he had some years ago cut off the fingers of the right hand of Gholam Ali, who was caught robbing a caravan near Dehbid, of which village Assad Ullah Khan was at that time the Governor. The blackhearted ruffian, whose nickname was “Cut Hand,” was so furious that his eyes became red, and he swore that, in revenge: he would shoe Assad Ullah Khan with horse-shoes; [4] and that he would only grant him a respite until he had collected the booty.

[ p. 209 ]

(Only the thumb of the right hand is left)

W. Carter,. phot.

[ p. 210 ]

[ p. 211 ]

A. Wright, phot.

Everything belonging to us was seized. Personally I had not brought much money with [212] me, as I had a bill on a banker at Meshed, and had sent the horse presented to me by the prince back to Kerman; but Mahmud Khan, who was old fashioned and loved to keep his money under his quilt at night, had seven hundred tomans with him, and in spite of his curses and entreaties all of it was taken. As the verse runs:

You may shout or cry; but the thief will not return the robbed goods. Our carpets, clothes, and rifles were seized; but the property of a mullah, who was a Sayyid, was restored. In short, we were stripped of everything except our underclothes, and those who resisted were badly beaten.

O readers of London and the New World, imagine our sad plight as we, who in the morning had owned horses, mules, and camp equipment, crawled miserably into Saghand with but a lame mule and a donkey which the robbers did not require. Ali Khan alone, like the light youth he was, kept repeating: “Respect is in Contentment; Disgrace is in Avarice,” until we all begged him for Allah’s sake to hold his peace.

Mahmud Khan was violently angry and behaved like a madman, at one time cursing the robbers, and at another vowing that his two servants, who had been ordered to keep watch, but who had slept, should eat a thousand sticks.

Everything, fortunately, has an end; but, [213] upon our arrival at Saghand in a pitiful state of fatigue, judge of our surprise when we saw Assad Ullah Khan seated outside the house of the headman of the village smoking a water pipe. “O Allah, what do I behold? Am I asleep or awake?” and a thousand other expressions rose to our lips; but the Khan said, “Did you not know that the Shirazis are clever, and I who am not less clever than the other Shirazis, told the servant of Gholam Ali, who was guarding me, that I had two hundred tomans sewn up in my quilt. He, like all ass, believing me went off to find the money; and I quietly stole behind the caravanserai where Gholam Ali had left his horses, mounted one of them and, riding down a water-course, escaped. He completed his story by quoting: ”If Allah wills, an enemy becomes a source of good.”

At Saghand we met Haji Aga Mohamed, a merchant of Kerman, and, thanks to him, we were able to continue our journey without having to beg for our bread. Indeed, like the masters of wisdom that we were, we gradually ceased to eat grief, and Mahmud Khan finally forgave his servants, who incessantly begged me with tears to intercede for them, which I was bound to do. In short, I represented to Mahmud Khan that “Allah takes the boat whither He will; let the boatman tear his clothes in grief.”

| Chapter XI. Yezd, the Prison of Alexander | Title page | Chapter XIII. The Arrival at the Sacred Threshold |

¶ Footnotes

201:1 Jafar was the sixth Imam. ↩︎

203:1 This is the Persian term for the ostrich, which ranged the Lut many hundreds of years ago. ↩︎

204:1 These wind-towers are high chimneys, and convey a draught of air to subterraneous rooms which are resorted to during the summer. ↩︎

204:2 This refers to the Persian word for avarice, which is spelt by three letters, none of which are dotted. ↩︎