[ p. 17 ]

“The Baluch are a people with savage faces, evil hearts, and neither morals nor manners.”— Mukaddasi.

I had just reached my fourteenth year when my father was summoned to Kerman, where he remained for several days. Upon his return he informed us that he had been appointed as Commissioner to settle the affairs of Baluchistan, which were in a most disordered condition.

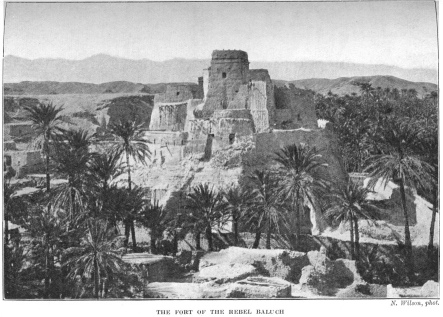

Now perhaps you do not know that, owing to its deserts, its savage people, and its remoteness, Baluchistan had only recently been subdued by the victorious Shah, Nasir-u-Din. In consequence, the Baluchis, hating Persians both as their conquerors and the introducers of civilisation, had rebelled and were besieging the Persian Governor in the fort of Bampur.

Fortunately Bampur was strong, well provided with supplies, and occupied by a considerable garrison; but, as the wild Baluchis had assembled [18] in their thousands, and had beaten back army after army sent to relieve the fort, the garrison began to lose heart, praying “for a hand to appear from the Unseen.”

The Governor-General wisely decided to send a strong force, with many guns, which the Baluchis especially fear; and, even more wisely, he appointed my father to command it. For, during the years that he was Governor at Mahun, my father, who was of immense stature, by his activity, his faultless marksmanship in hitting an egg while at full gallop, and, above all, by his courage, had made such a reputation for himself that men compared him to Rustam, and swore that he too would have rescued Bijen out of a well, or performed any other of those great feats that have made Rustam’s name famous throughout the Seven Climates.

A Khan once asked my father how it was that he who was the son of a man of letters always displayed such extraordinary bravery and all other qualities of the men of the sword. He replied, "One day, when I was sixteen years old, I was reading poetry, and by chance I read these lines:

If lordship lies within the lion’s jaws,

Go, risk it, and from those dread portals seize

Such straight-confronting death as men desire,

Or riches, greatness, rank, and lasting ease.

[ p. 19 ]

He added, “I was so fired by these verses, which I kept repeating hourly to myself, that ever since I have been proof against all fear.”

By Allah! few men had such a father as I have had! As the poet says:

If you want to succeed to the inheritance of your father,

Acquire your father’s attainments.

A week was spent in making arrangements for transport, in arming and clothing the whole party, and also in packing up large supplies, not only of cartridges, but also of tea, sugar, and other stores, for, in Baluchistan, not even a packet of candles can be purchased. During all this time I had been begging my father’s chief servants to intercede for me to be allowed to go in his service, and, at last, to my joy, my father, who rarely spoke to me, said, “Dost thou wish to see the deserts of Baluchistan?” I replied, “Whatever Your Excellency orders I obey.”

My father thought for a while and then said, "How can I expose a raw youth like thou art to the hardships of such a journey?

If thou art not a lion, do not pass through a lion-infested jungle,

For many a brave man is sweltering in his own blood there."

Whereupon I made bold to quote the following verse:

Much travelling is needed to season rawness.

[ p. 20 ]

I could have quoted more fine verses but was overcome with shame. My father, however, seemed pleased and remarked, “Thou, my son, art indeed raw; but Inshallah, the sun, the desert, and the hardships will season thee.” Thus my father ordered, and, although my mother wept continuously for three days, it was all in vain; indeed it only made my father angry.

We quitted Mahun before the winter set in, and, consequently, we felt it quite hot when we reached Bam, where I saw date-palms and orange trees for the first time in my life. Our party was met by the general of the troops and one hundred sowars; and two infantry regiments lined the river-bed which divides the town into two quarters.

For some days we halted to make final arrangements for the large force, of which my father had now assumed the supreme command, and, as I was without work, I spent the time in studying the history of Bam and visiting its famous buildings, for thus early did my love of history show itself.

Chief among the sights of Bam is the famous fort, which is considered to be the strongest and the loftiest in the world, and, indeed, after carefully examining it, I think that this is proved. In short, as the verse runs:

[ p. 21 ]

A fort so high that if the sky should try to have a look at its towers, the golden crown will fall from its head.

I accompanied my father when he inspected it, and, even before the outer gate was entered, a steep ascent cut in the rock had to be traversed. The outside wall, which rose above us to a great height, was passed by means of a gate fit for Rustam’s house; but, to my surprise, we only entered a narrow lane, and saw a second wall even higher than the first, rising up almost out of sight.

After proceeding for some distance we saw vast stables, and then entered the main part of the fort by an equally formidable gate up a still steeper incline. Passing the rows of great cannon, we had yet a still harder climb through a subterranean passage to the summit of the fort, where the sleepless commander kept watch and ward.

Here we were shown a well, dug by the king of the Divs at the order of the great Rustam, who vanquished them. Close by was a set of rooms, opening in every direction, and known as a Chahar Fasl or “Four Seasons,” where breakfast was served.

I rejoiced at seeing this, as I had been frightened and my head had turned round from awe of this stronghold; but soon I felt happy and proud that the Shah, may Allah make his [22] reign eternal! possessed such a fort, which the savage Baluchis see from their lairs in their naked deserts, and tremble at the majesty and might of Nasir-u-Din Shah, the Sun of Kings, the Ornament of the Country, and the Pride of the Crown and Throne.

My father, who had twice before travelled in Baluchistan, pointed out the peak of Kuh-i-Bazman, distant some forty farsakhs; [1] but so high is it, and withal of so elegant a shape, that there is no mountain in Persia to equal it in beauty. They say that, on its summit, is a shrine to Khedr or Khizr, [2] he who guides the steps of the wayfarer; but few among mortals have ascended there. Indeed, as only Baluchis, who climb like goats, could scale the peak, which resembles a sugar loaf, I cannot vouch for the accuracy of this statement; but, at any rate, by them the peerless mountain is termed Kuh-i-Khedr-i-Zinda, or “The hill of the Living Khedr.”

Perhaps, O my readers, you are not acquainted with the story of how Khizr was deputed by Allah the Omnipotent to instruct the prophet Musa or Moses. For he, being lifted up with pride at his own knowledge and wisdom, asked of Allah whether there was any one in the world [23] wiser than himself. Allah reprehended him for his vanity, and acquainted him with the fact that Khizr was wiser than he was; and bade him to go to a place where the two seas meet.

There he found Khizr and said unto him, “Shall I follow thee, that thou mayest teach me part of that which thou hast been taught?” But Khizr replied, “Verily thou canst not bear with me: for how canst thou patiently suffer those things, the meaning whereof thou dost not comprehend?”

However, Musa begged him and Khizr agreed, on the condition that no questions should be asked until he himself explained his reasons.

So they both went to the sea shore and entered into a ship, in which Khizr made a hole. To this Musa objected, saying, “Hast thou made a hole therein to drown those on board?” Khizr rebuked Musa, who excused himself for breaking the agreement.

They then left the ship and proceeded by land until they met a youth, whom Khizr immediately slew. This again aroused Musa to remonstrate, and Khizr answered that they must separate, but that first he would explain his acts.

The vessel, he said, belonged to certain poor men who gained their living by the sea; and he [24] had made it unserviceable because there was a king behind them, whose emissaries were seizing every sound ship. As to the youth, his parents were true believers, whereas he was an unbeliever; and so he was killed to save his parents suffering from his perverseness and ingratitude.

Finally, he said, “I did not what thou hast seen of mine own will, but by the direction of Allah.”

We left Bam early one morning and the whole town accompanied us for a farsakh on the road, many of the women weeping as if their husbands were already dead, so evil a reputation does Baluchistan bear. As the Arab poet wrote:

O Allah, seeing Thou hast created Baluchistan,

What need was there of conceiving Hell?

For two stages, however, we travelled through delightful jungles full of game, and how I enjoyed being allowed to ride near my father, and to shoot at the francolin as they rose out of the thickets. Indeed I thought that if Baluchistan was at all like Narmashir, it was a delightful country.

However, on the fourth day after leaving Bam, the jungle suddenly ended, and we looked across such a sterile, naked desert that my gallbladder felt as if it had burst. Indeed, even at the first stage the supply of water was the greatest [25] difficulty, as my father had arranged for 700 camels to carry forage and provisions; but to cross fifty farsakhs of desert where there is only a small well at each stage is very difficult.

In fact, that night there was a quarrel between the Narmashir sowars and my father’s servants, which nearly became serious; but His Excellency heard of it and, when he came up, every one stopped fighting. As they say:

When the lion appears, the jackal is silent.

For ten days we crossed the dry, empty desert, and although we never saw a human being, there was no fear of our losing the way, as every mile we rode we passed the dead body of a camel or of a donkey. Occasionally, too, we saw the corpses of men whose strength had failed them between the wells.

However, everything at last comes to an end, and, when we sighted in the distance the thick jungle which grows on the banks of the Bampur river, we forgot all about the Baluchis and thought that we had reached the garden of Shaddad. [3]

My father, like the man of experience he was, gave orders that a strong party of sowars should go ahead at early dawn in three parallel bodies, as he feared an ambush; and this was [26] very fortunate, as one of the parties of sowars under Colonel Mohamed Ali Khan, seeing no signs of the enemy, went down to the river and watered their horses without taking any precautions.

The Baluchis, however, were in ambush, and fired on them, killing and wounding twenty men, and had not the other two parties come to the rescue there would have been a disaster. My father was so angry with the colonel that that night he ate [4] five hundred sticks and was ill for weeks afterwards.

We halted for some days at Kuchgardan to rest the troops, whom my father encouraged daily to distinguish themselves by addressing them, and by having passages read from the Shah Nama, in which the exploits of all the heroes of Iran are recounted; and, by Allah! were all Persian generals like His Excellency, no army would ever stand before the victorious troops of the Shah.

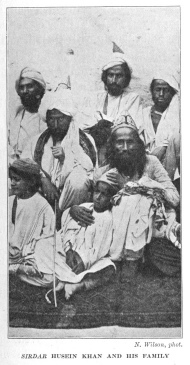

While we were halting at this stage, Nawab Khan, Bamari, and his tribe, who alone of Baluchis are Shias, and who are thus loyal to the Shah, joined our camp, and informed His Excellency that Sirdar [5] Husein Khan, Nahrui, who was the leader of the Baluchis, was camped

[ p. 27 ]

A farsakh from Bampur fort, and was, like all Baluchis, quite careless at night. He thus advised that he should be surprised in the dark. My father, however, like Iskandar Zulkarnain, [6] [ p. 28 ] replied that he would not steal a victory; and indeed he sent Sirdar Husein Khan a stern message, to the effect that either he and his men must come immediately with their hands bound and throw themselves at his feet, or else, within three days, their bodies would become food .for the crows and kites. Within a few hours came back the reply that the Sirdar was awaiting the honour of receiving a guest!

My father, who knew that the Baluchis would try to ambush his army, as they had done successfully before in the case of two Persian forces, decided to ambush the ambuscaders.

He therefore arranged that the infantry and artillery with the baggage should march along the main road through the jungle under Suliman Khan, while he himself with the sowars left the camp at night, and, after marching towards Bam for a short distance, took a wide detour and formed an ambush close to where the main body would pass.

In the morning his spies reported that the whole force of the Baluchis was in ambush, exactly as he had anticipated; and very soon shooting was heard and cries of alarm from the main body, which was being attacked.

My father then mounted Raksh, [7] his great

[ p. 29 ]

[ p. 30 ]

[ p. 31 ]

war-horse, and, turning round, his face was so terrible with his eyes blood-red, that I felt that to be killed by Baluchis was nothing to arousing my father’s wrath. In short, that face inspired us all to become devotees of death, and, charging through the jungle, we fell on the Baluchis, who felt sure that this, the third Persian army, was already their prey.

I followed behind my father, and saw him with one stroke cut the son of the Sirdar into two pieces, just as Amir, [8] on him be peace! cleft Marhab of Khaybar with his famous sword, Zulfikar.

This sight threw the enemy into a panic and they all rushed to their riding camels, for Baluchis always fight on foot. Nawab Khan, however, had already seized the camels, and so their only hope was to scatter and hide like rats; and this they did, being chased by the victorious Persians, who did not slacken the pursuit until their horses fell from fatigue and their sword-hilts stuck to their hands.

My father offered ten thousand tomans for the head of the rebellious Sirdar; but he escaped towards Rudbar, and it was not until a month later that it was reported that he had died of his wounds in the desert. Thus may Allah [32] destroy all rebels against the ever-victorious Shah!

In the evening we rode on to Bampur, but it was not until we drew quite close that the gates were opened and a handful of fever-stricken shadows tottered out to welcome us. One of these was Haji Sohrab Khan, the lion-hearted defender, whom my father at first did not recognise. When he knew who he was he threw himself off his horse and embraced him, and all of us wept to hear that only fifty men of the garrison of six hundred were alive, and that, had the dogs of Baluchis assaulted the fort, instead of merely blockading it, a calamity would have occurred.

My father ordered the camp to be pitched outside the fort; and I remember with dread how, without even washing his hands, which were reeking with blood, he ordered food to be served without delay.

In a month the justice of my father had drawn the Baluch Sirdars to his footstool, and they represented that they had been led astray and now repented deeply. His Excellency replied, “Allah forgives the repentant sinners”; and as he saw that their hearts were as water, and that they would not rebel again, he showed [33] condescension to them and forgave them their wickedness.

At the same time he took hostages from every tribe, and thus, with increased dignity, enhanced reputation, and great honour, he returned to Kerman, where the Vakil-ul-Mulk treated him as his son, and the Shah honoured him with the high title of Shuja-u-Saltana or “The Champion of the State”; and Allah knows that this title was befitting, and its bestowal proved that the Shah was ever on the look-out to reward valour and zeal displayed in the royal service.

¶ Footnotes

22:1 A farsakh is about four miles. ↩︎

22:2 Khedr is the Arabic, and Khizr the Persian form. ↩︎

25:1 A legendary garden lost to human gaze. ↩︎

26:1 To “eat sticks” is to receive the bastinado. ↩︎

26:2 Sirdar is a title signifying a high chief in Baluchistan. ↩︎

27:1 Sc. Alexander the Great. Zulkarnain signifies “Lord of two horns,” an epithet implying might. ↩︎

28:1 The name of Rustam’s famous charger. ↩︎

31:1 Amir is the title by which Ali is referred to by Shias, signifying thereby that he is the commander of the Faithful. ↩︎