[ p. 34 ]

Bring wine! let first the hand of Hafiz

The cheery cup embrace!

Yet only upon one condition

No word beyond this place!

HAFIZ.

About a month after our return from the war in Baluchistan, His Excellency the Vakil-ul-Mulk informed my father that he would honour him by being his guest at luncheon on the following Friday.

This information threw the entire household into a state of great excitement; and when it is remembered that the Vakil-ul-Mulk never honoured a Khan with an escort of less than three hundred sowars, apart from the nobles of the province who were in attendance, and who also had their retinues, it may be understood that even to provide accommodation for so

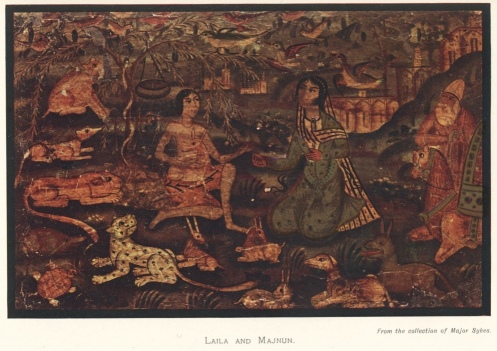

From the collection of Major Sykes.

[ p. 35 ]

many people and forage for so many horses was, in itself, a heavy task; and that heavy task was laid on me.

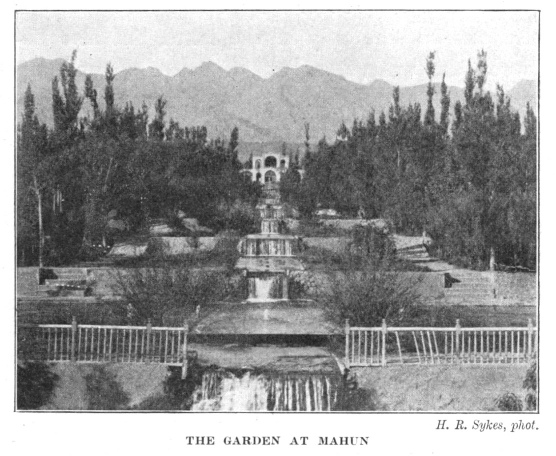

However, thanks be to Allah, the garden at Mahun was fitted to receive even such a distinguished guest as the Vakil-ul-Mulk; and, since

H. R. Sykes, phot.

it is one of the famous gardens of Persia, itself a land most famous for gardens, it is right that I should describe its beauties to you.

We Persians, whenever possible, build our gardens on a gentle slope; and the garden I am describing was so constructed that two streams of crystal-like water met in front of the building and formed an immense lake, on the surface of [36] which numerous swans, geese, and ducks disported themselves.

Below this lake there were seven waterfalls, just as there are seven planets; and below these again there was a second lake of smaller dimensions, and a superb gateway decorated with blue tiles.

Perhaps the reader may think that this was all; but no, not only in the lakes, but also between the waterfalls, jets of water spouted up into the air so high that the falling spray resembled masses of diamonds. And often, when reclining in the beautiful tiled room, the plash of the jets of water and the murmur of the stream hurrying down the terraced garden between rose bushes, backed by weeping willows, planes, acacias, cypresses, and every other description of tree, have moved me strangely; and I have wept from pure joy, and have then been lulled to sleep by the overpowering sense of beauty and the murmur of the running water. By Allah! I think, indeed, that this garden is not surpassed in beauty by even that famous garden mentioned in the Koran:

The garden of Iram, adorned with lofty pillars:

The like of which had not been created in the world.

On the appointed day, one hour before noon, my father, his chief officers and myself, duly met the Vakil-ul-Mulk at the main gate. His Excellency was in a truly good humour, and, in [37] reply to my father’s welcome and assurance that “the garden was a gift to him,” replied that he regarded him as his own son. To this my father, with proud humility, answered “I am a slave born in your family.” His Excellency next said that he had heard a good report of me, which made me hang my head from modesty.

Accompanied by the nobles, the Vakil-ul-Mulk walked along the edge of the lake with great dignity and very slowly, for, in Persia, only Europeans and men of low extraction walk quickly. He then ordered some bread to be brought, and fed the swans for quite a long time, while we stood waiting in attendance.

At length His Excellency entered the chief room alone, and we all stood respectfully outside by the open windows.

Opposite the cushions, on which the Vakil-ul-Mulk reclined, were two large trays full of sweetmeats prepared in the women’s apartments. Among these were toffee, almond paste, “elephant’s ears” in pastry, burnt almonds, sugar drawn as fine as hair, and many other delicious sweetmeats which are only made in Iran. There was also a box of manna from Isfahan. Between the trays of sweetmeats was a silver tray, on which was spread an exquisitely fine shawl, worth at least two hundred tomans [1]; and on [38] the shawl was a sealed packet, containing two hundred ashrafis or gold pieces.

The Vakil-ul-Mulk tasted the sweetmeats, and, looking at the jets of water shining in the sun and the lovely garden, repeated:

If there is a Paradise on the face of the earth:

It is this, it is this, it is this.

His Excellency then invited his Vizier and my father to enter by a nod of the head; and, in the same manner, he dismissed the nobles and his attendants, who were shown by me to the different rooms prepared for them, as the chief servants all have their separate staffs, and so have to sit in separate rooms.

The Vakil-ul-Mulk again tasted the sweetmeats, and especially praised the toffee and also the manna which, with quails, formed the food of the Beni Israel [2] during the forty years they wandered in the deserts; and my father bowed low to express his gratitude.

Tea was then served, and the special water pipe of the Vakil-ul-Mulk, of beaten gold studded with turquoises, for which Iran is famous, was brought in.

After pulling at it in silence for a minute, His Excellency inquired from his chief waiter where he had procured such excellent tobacco; and that official replied that it was given by my [39] father who, to grace the auspicious occasion, had bought up a stock that had reached Kerman on the previous day from Shiraz. He added that my father had supplied a large quantity of this tobacco if he might accept it. His Excellency said it was not needed; but finally accepted the gift, and my father afterwards gave the servant a handsome sum of money for his friendly behaviour.

After a while, my father represented that luncheon was ready to be served, and went into the adjoining room to superintend the spreading of the table-cloth, which is made of red Hamadan leather and covered with chintz.

The waiters of the Vakil-ul-Mulk, however, declined to spread the cloth without orders from the chief of the Private Apartments, who equally declined to pay any attention until the whispered promise of a gift made him energy personified.

On the edge of the cloth twelve flat loaves of very white flour were placed; and there were huge trays of plain rice boiled as only it is boiled in Persia, with the savoury browned parts, flanked by other mounds of rice, in which the flesh of lambs and chickens with raisins, almonds, and saffron were all skilfully blended.

The bowls of broth, the dishes of meat cooked in pomegranate or lime juice, or with walnuts, were smaller, and were placed in an [40] outer line, together with cheese, curds, vegetables, and preserved fruits.

At length all was ready, down to the priceless china bowls of sherbet, in which floated the translucent spoons of Abadeh in a mass of crushed ice, sherbet alone being drunk in public; and the Vakil-ul-Mulk, on being informed that the luncheon was served, rose from his cushion and, walking to the next room, seated himself in the place of honour.

After having partaken of some food with a good appetite, His Excellency gave orders that the Vizier and my father should be sent for. They appeared, bowed low, and were honoured by being invited to join the Governor-General, whereupon they sat down very respectfully in the lowest place. This was, in truth, a great distinction for my father, as His Excellency always sat down alone to meals, not even permitting his sons to partake of food in his presence.

Kabobs of gazelle were brought in, wrapped up in a piece of bread to keep them hot; and His Excellency said that it was not necessary to ask who lead shot it.

The repast was eaten almost in silence; and so large were the mounds of food that they seemed almost intact when, after tasting a Natanz pear preserved in syrup, and praising its [41] flavour, the Vakil-ul-Mulk called for the jug and basin, with which he washed his hands and beard, for you must know that we Persians not only sit on our knees, but, like the Prophet, on Him be Peace, eat with our fingers, rolling together our rice into balls and then inserting them with our thumbs into the mouth.

In later years I once saw an English officer try to do this, but we all agreed that he ate just like a tiger, and that only Persians could eat, in this fashion, in a refined manner; also we know by experience that food eaten with the hand is of a better flavour, and that it is impossible to satisfy the appetite if knife and fork be used.

After this the Vakil-ul-Mulk retired with his most confidential servant for a siesta, and then, and not until then, was the sealed packet of gold coins opened and the shawl examined. His Excellency reclined on a cushion embroidered with pearls, on which was placed a large pillow and a second very small one, stuffed with swan’s down, brought from the province of Sistan. A thin silk coverlet kept off the flies.

The confidential servant, when his master had composed himself to sleep, went out, gently closed the door, and lay down outside ready to be in attendance when summoned.

In less than an hour a cough announced the awakening of the Governor-General, who again [42] washed his hands and face, and carefully combed his majestic beard, his moustaches, his eyebrows, and even his black eyelashes. He then arose, proceeded to the chief room, and, sending for the Khans and his attendants, said that, as it was too hot to go outside, he wished every one to sit down. After this he ordered tea to be served.

The conversation turned on allusion, in which Persians excel, and the Vakil-ul-Mulk himself, who was in a remarkably good humour, and did not order a single servant to eat sticks that day, told us of how Mahmud of Ghazni requited Firdausi, the author of the greatest poem in the world, so inadequately, that the poet wrote a famous satire on him which runs:

Long years this Shahnama I toiled to complete,

That the King might award me some recompense meet,

But naught save a heart wrung with grief and despair

Did I get from those promises empty as air!

Had the sire of the King been some Prince of renown,

My forehead had surely been graced by a crown!

Were his mother a lady of high pedigree,

In silver and gold had I stood to the knee!

But, being by birth not a prince but a boor,

The praise of the noble he could not endure!

Fearing retribution, Firdausi wisely fled some days before the satire was delivered, and ultimately took refuge with the Sipahbud of Tabaristan, who was the only prince of Persian descent reigning in Persia, which was then unhappily divided into separate principalities.

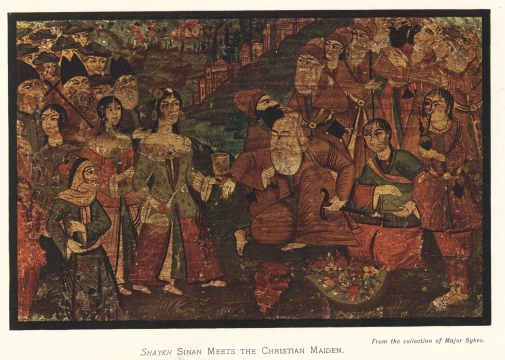

From the collection of Major Sykes.

[ p. 43 ]

Sultan Mahmud was so furious when he read the satire that he fainted from excess of anger. He then sent messengers with copies of the poet’s portrait to every court to inquire whether Firdausi was there, and on finding that he had taken refuge in Tabaristan, he wrote to the Sipahbud demanding the surrender of the poet, and ended his letter by threatening that, if his desire were not complied with, he would come with his war elephants and trample the country beneath their feet.

The Sipahbud, who was prepared to defend his guest to the death, sent back the Sultan’s letter and merely wrote “Alm” on the back. Mahmud was too ignorant to understand what this meant and was utterly amazed; but one of his Persian courtiers at once explained that by “Alm” the Sipahbud intended to remind the Sultan of the fate of Abraha the Abyssinian, who, also relying on war elephants, invaded Mecca in the very year of the Prophet’s birth; but Allah the All-wise did he not cause flocks of birds to pelt them with pellets of baked clay so that they were discomforted? He added that the “Chapter of the Elephant” began with “Alm.” When Sultan Mahmud understood this matter he trembled, and his threat remained unfulfilled.

For a long while every one was silent, and [44] then the conversation turned to the politeness of Persians, and Husein Ali Khan said that when he was an attendant at the foot of the throne of Mohamed Shah there was a great dispute with the Minister of France because the Governor of Shiraz had, so he averred, seized a large sum of money, twenty thousand tomans, belonging to a French merchant, whereas that trustworthy official explained that he had merely taken charge of it to save it from Kashgai robbers.

In any case, at the fête in honour of the birth of the Shah, when the Chief Vizier gave a banquet, the Minister refused to be among the guests unless this sum were paid; and this abstention being reported to Mohamed Shah, that exalted monarch was displeased.

Finally, the noble Vizier not only paid the money from his private purse, but, greeting the Minister of France with exquisite urbanity, he said: “Your Excellency, this banquet has cost me twenty thousand tomans; but I would gladly have paid double the sum for the pleasure of entertaining the Minister of France.” Hearing this, we felt that it was in Persia alone that such noble, high-souled ministers were born; and we all thanked Allah that we were Iranis.

The Commander-in-Chief then said that, not only in allusion and in politeness were Persians far ahead of all other nations, but that in astuteness there was no other people even second to them.

[ p. 45 ]

[ p. 46 ]

[ p. 47 ]

In proof of this, he told us that on one occasion he had to pay his regiment about ten tomans a man; but, owing to his misfortunes, he had only a hundred tomans instead of the necessary five thousand. However, astuteness came to his aid, and he paid every man his due, made him seal his receipt, and then, as he passed into an outer room, the money was taken from him and returned. In short, after paying away five thousand tomans, he had still a hundred tomans left. At hearing this every one laughed, and the Vakil-ul-Mulk called the Commander-in-Chief a blackguard; but only in jest.

Shaykh Ahmad then said that he knew of yet another story connected with Sultan Mahmud, who, the son of a slave, rose to be a mighty monarch and thirsted for a title from the Caliph. He sent a large gift to the Caliph, but nothing for his Vizier, who was, of course, a Persian, and who, in drawing up the order, gave instructions that Mir should be written instead of Amir.

Now Mir means a chief, but also a slave; so Mahmud was furious at this insult, until a Persian courtier explained to him that the “A” [3] which was omitted conveyed a delicate [48] hint that he had not sent one thousand gold coins to the Vizier; but that, if the order were returned with that sum, no doubt apologies would be made and a fresh order, written as His Majesty desired, would be sent. And so, by Allah, it turned out; and thus was Sultan Mahmud educated by clever Iranis.

Abu Turab Khan represented that he could give a case which had happened only a few years ago at the court of the Vakil-ul-Mulk, but that he would not dare to mention it without permission. His Excellency was very curious to hear the story, and agreed to pardon the Khan, who said that, three years ago, a Tehran merchant came down to examine into the accounts of his agent, who had been in charge of his land for ten years and who had embezzled thousands of tomans.

But this agent was very clever, and so he paid the chief executioner two hundred tomans to come secretly to the Tehrani the morning after his arrival, and whisper in his ear that orders had just come by telegram to the Vakil-ul-Mulk for him to be thrown into chains and sent back to Tehran.

This so alarmed Aga Hadi that he too paid the chief executioner two hundred tomans and, mounting his horse, he rode off and never returned to Kerman!

Hearing this, the Vakil-ul-Mulk rolled on the [49] ground, helpless with laughter. He then called for the chief executioner and asked him if this were true, and finally it was acknowledged.

“Blackguard,” screamed the Vakil-ul-Mulk, and again rolled over.

“By Allah!” quoth he, “how fast Aga Hadi must have ridden, and how tired such a fat man as he is must have been!”

It was now two hours to sunset, and His Excellency exclaimed, “Bismillala! let us go.” Everything was in a tumult, all the chief servants shouting out their orders; but by the time His Excellency had walked slowly past the lake to the great gate, his carriage was ready, guarded by three hundred sowars; and, preceded by mounted attendants bearing silver maces, who shouted out to clear the road, the stately cortège disappeared in a cloud of dust on the road to Kerman.