[ p. 102 ]

Many are the famous and many are the fortunate,

Who have rent the garment of life,

Who have drawn the head within the wall of the grave.

Sadi.

IT was about three years after my marriage when my uncle addressed me with much solemnity and said, "Oh my son, up to the age of forty years a man develops; but after this he remains stationary, just as the sun when it has reached the meridian seems to stop, and then to move more slowly until it begins to set.

"From forty to fifty years a man feels that he is failing every year, but after reaching this age he feels it every month until he is sixty, when he feels it every week. Now I, my son, have passed seventy years, and, as the poet writes:

“Hast thou won a throne higher than the Moon;

Hast thou the power and the wealth of Solomon!

When the fruit is ripe, it falls from the tree;

When Thou hast attained thy limit, it is time to depart.”

[ p. 103 ]

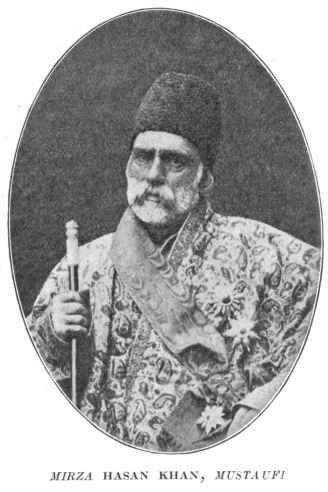

A few days after speaking these words, Mirza Hasan Khan fell ill with fever, and so Haji Mohamed Khan, the Chief Physician of the quarter, was summoned. At first he encouraged us by giving proofs of his perception, as he said to my uncle that he knew that he had partaken of fowl that day, which happened to be true; and Allah alone knows how he was aware of this, unless indeed he saw its feathers lying outside the kitchen.

The Chief Physician, after making the most minute inquiries, ordered that all pickles and all white foods, such as milk, cheese, or curds, should be given up; and he prescribed a broth of meat, vegetables, and rice all boiled together.

He added that it was most important that the meat should be cut from the neck of the sheep. Moreover, as the disease was pronounced to be of a cold type, castor oil, which is a warm drug, was administered as a purgative, followed by boiling water containing sugar.

It was expected that, on the seventh night, perspiration would set in; but as the fever was still strong, the legs of the patient were fumigated and mustard was rubbed in. Perspiration was again expected on the ninth night; but as there was no abatement in the fever a family council was held, and it was decided to call in [ p. 104 ] Mirza Sadik Khan, the Chief Physician of the Vakil-ul-Mulk.

This physician was famous throughout the province for having cured a man who was at the point of death from a bone sticking in his throat, and as, perhaps, some European doctor may read this story, I advise him to note how this successor of Avicenna added lustre to the glories of Persian science.

The patient was brought in on the verge of death, and when his condition had been described, the learned physician stroked his long beard and exclaimed, "By Allah! this case would be hopeless except for me, whose perception is phenomenal. The cause of this man’s state is a bone lodged in the throat so firmly that no efforts avail to dislodge it. Therefore either the man must quickly die or the bone must be dissolved, and by what agency?

“Thanks be to Allah! I am a physician and a Kermani, and have observed that wolves, who live on raw meat and bones, never suffer any calamity such as that of the patient. Therefore it is clear to me that the breath of a wolf dissolves bones, and that, if one breathes down the throat of the patient, the bone will be dissolved.”

Infinite are the marvels of Allah! for when a wolf, belonging to a buffoon, was brought in and [105] breathed on the patient, suddenly a fit of choking ensued, and the bone, dissolved without doubt by the breath of the wolf, was loosened and extracted.

Since that date the Vakil-ul-Mulk would consult no other physician, and occasionally condescended to remark that his physician was fit to rank with Plato.

However, the arrival of the Governor-General’s doctor much displeased Haji Mohamed Khan, and when Mirza Sadik Khan declared the disease to be of a hot type and prescribed broth composed of the flesh of cocks which are cold, as opposed to hens which are hot, in addition to a draught of water-melon juice with melon seeds; and, finally, when he entirely forbade the use of salt, there was a great quarrel, so much so that my uncle bade them, in Allah’s name, to leave him to die in peace, and to allow him to follow the path of her who is forgiven, meaning thereby his deceased wife.

He also quoted from the Koran, “Wheresoever ye be death will overtake you, although ye be in lofty towers.”

At this time Izrail, the Angel of Death, was, in truth, knocking at the door; and that no one can stay his entrance, is shown by what happened in the case of the Prophet, on Him be peace!

[ p. 106 ]

It is recorded in the Book of Calamity, and runs as follows [1]:—

Izrail.—Here is one of the least servants of Mohamed, the King of the Faithful. Let some one be kind enough to come to the door, for I have a message to deliver.

Fatima (at the door).—Who is that knocking at the door? And what can have induced him so to do? Is his thunder-like voice going to strike my soul dead?

Izrail.—Know thou, O daughter of the Prophet, that I am a stranger come from a distant country to receive light from Mount Sinai of Arabia. Be pleased to open the door and allow me to enter, for I have a knot to be untied inside.

The Prophet.—Dost thou not know, Fatima, who is he that knocks at the door?

Fatima.—No, father, I any unable to tell who that rough-spoken man is. I can only say that his dreadful voice has made me quite restless.

The Prophet.—It is he who continually grieves the heart of men; he who casts the dust of misery on the heads of poor widows. It is he, even the snatcher of the souls of men, Jinns, beasts, and birds; he can command a full view of the east and west at the same time.

Fatima.—Oh! what shall I do? The time of trouble has, after all, arrived, the hour of affliction approacheth. Come in, O thou Snatcher of Souls, and say what thou wishest to do, for thou art permitted by the Prophet to enter.

Izrail.—Peace be unto thee, O Mighty Sovereign! Peace be unto thee, O Sun of the World!

The Prophet.—On thee be both peace and honour! Thou art altogether welcome. What may thy object or message be? Tell us.

[ p. 107 ]

Izrail.—May I be offered unto thee, O thou King of Freedom and Liberty! The Creator of the World has sent me to the earth to thee, to know whether it be thy pleasure that I should transport thy soul from thy body to a garden of roses and jasmines, or whether thou preferest rather to live eternally on the earth. Thou mayest choose which thou likest best.

The Prophet.—In the pleasure-garden of this life every beautiful rose is attended with several piercing thorns, and the treasure of this world has many venomous serpents accompanying it. Thus thou mayest take my life if thou pleasest.

To return to the state of Mirza Hasan Khan, in despair a soothsayer was now called in. This individual, after repeating some cabalistic phrases, remarked that the patient had evidently been attacked by Jinns, either from passing along a canal at night without repeating the name of Allah, or else from putting his hand into hot ashes, which disturbs the young Jinns.

Neither of these things had Mirza Hasan Khan done; but still we felt that something might be effected by the soothsayer; and so, when he proposed to summon the king of the Jinns in order to inquire, we agreed.

Thereupon he asked for a basin of water; and we were all instructed to put money into it, in accordance with the love and regard we had for the patient. When I threw in a gold piece the soothsayer, with extraordinary gestures, chanted the following verse:

[ p. 108 ]

I adjure you, by the names of Allah, those of you who live in buildings and those who reside in deserts and uninhabited places, that you present yourselves before me to listen to my order and to execute it. All of you who are riding horses should appear, accompanied by your kings and princes; and all who are present or who are absent should appear, so that I may see you and speak to you in your own language, and obtain replies from you to the inquiries made from you as regards the treatment of this patient. Help, O Angels Rakyail, Jibrail, [2] Mekiail, Sarfiail, Ainail, Kamsail, in producing these Jinns.

Suddenly the soothsayer foamed at the mouth to make us believe that Shamhurash, the King of the Jinns, had entered him, and a dialogue ensued, during the course of which Mirza Hasan Khan was accused of various offences against the Jinns, such as sitting at night under a green tree without repeating the name of Allah; throwing stones at the heaps of house-sweepings, the usual place of rest at night of Jinns and their children; throwing a bone, and thereby hurting the Jinns; finishing his meals without leaving anything; or throwing a half-burnt piece of wood without uttering Allah’s name.

At length it was decided that a black cock should be sacrificed, and a charm written with its blood and placed underneath the pillow of the patient, who also was ordered to eat its liver raw; but, alas! my dear uncle was dying, [109] and, after mourners’ tears had been administered in vain, [3] he was gently laid with his face turned towards Mecca, while the “Yasin” chapter of the Koran was recited.

After this the dying man was called upon to make his will in the presence of witnesses; and he bequeathed one-third of his property for services in connection with his funeral, a pilgrimage by proxy to Mecca, and the reading of a special series of prayers at the shrine of [110] the Imam Riza. The other two-thirds of his property, consisting of a house, a garden, and four parts of a village, were bequeathed to me. The document was first sealed by the dying man, then by Aga Mohamed and other witnesses.

When the will was drawn up and thus completed, my uncle’s seal was broken and placed at his right side; and his shroud was prepared, covered with the various prayers written by forty-one different individuals:

O Allah! we know certainly nothing but good about this person; but Thou knowest his condition better.

This is a testimony in favour of the deceased. And, as one of our deep-thinkers in utter humility and self-abasement wrote:—

We are ashamed to find on the Day of Judgment

That Thy forgiveness was too great to allow us to commit any sin.

When the death agony was passed my uncle’s eyes were closed, and, after his limbs were stretched, the great toes of both feet were tied together and a scarf was bound round the head under the chin. The corpse was next placed on a bier, and after being carried round the court of the house, was taken to the Washing Place, preceded by Allah Mughari, termed the “Ministers of Death,” whose duty it is, the moment a death has [111] occurred, to ascend to the roof of the house and to chant in Persian:

Whosoever has come into this world is mortal;

The one who alone remains alive and everlasting is Allah.

Moreover, they chant the names and attributes of Allah in Arabic, whereby the fact of the decease is notified.

The corpse at the Washing Place was laid on a flat stone. The clothes were first removed, and it was washed with pure water, with water and soap, with water in which leaves of the lote tree had been mixed, and, finally, with camphor water. It was then wrapped in the shroud, which was fitted by tearing off suitable lengths, no thread or needle being allowed to touch it.

Two green willow sticks were placed under the arms, on which were traced, by the finger alone, the following words:

Certainly we know nothing but good of this person.

It is believed that so long as the sticks are left in the tomb, so long the corpse remains untouched by time.

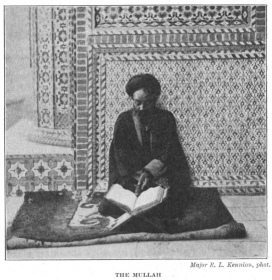

When the corpse had been duly prepared, it was replaced on the bier and the funeral procession started for the cemetery. First came the relations, then the dead man carried by relays of voluntary bearers, and followed by a mullah on horseback, who recited the Al [ p. 112 ] Rahman chapter of the Koran. Behind came numerous friends, and the procession was lengthened by led horses, sent as a mark of respect to the late Mustaufi; there was also a catafalque draped with black cloth, and numbers of people bearing unlighted candlesticks. In short, before the sad procession reached the cemetery at least a thousand people had joined it.

Major P. I. Kennion, phot.

There the funeral prayer was recited by [113] the mullah, and the bier was removed to the foot of the grave. Three times was it lifted from the ground and three times was it replaced. At the fourth time the corpse was gently lowered head-foremost into the grave.

Earth from the tomb of the Imam Husein at Kerbela was lightly thrown inside the shroud, the face of the corpse was uncovered and the right cheek laid on the bare ground, with a little of the sacred earth under it, the face itself being turned towards Mecca. The grave was first covered with bricks sufficiently high to allow the dead man to sit up and reply to the dread questions of Munkir and Nakir. Earth was then piled up and the mullah recited:

O Allah! this person is Thy slave, son of Thy man-slave and woman-slave.

He is going to Thee and Thou art the best receiver of him.

Finally, water was sprinkled on the earth, and all present, opening their hands, buried their fingers in the soil in such a manner as to leave marks, reciting meanwhile the opening chapter of the Koran. As long as the finger-marks remain there the corpse will not, we believe, be subjected to any trouble. This concluded the burial ceremony.

But perhaps I ought to explain why these willow sticks are placed under the arms of the dead man, as otherwise the custom might [114] appear to be without meaning, whereas the contrary is the case.

When the burial is completed and the mourners have dispersed, the mullah stays behind and, standing with his face turned towards Mecca, he solemnly adjures the dead man thrice in the following words: “Hear and understand! When the two angels visit thee and question thee, fear not; but reply by the confession of faith. Hast thou understood?” He then concludes, “May Allah keep thee firm in thy belief and guide thee!”

When the angels, Munkir and Nakir, visit the dead man, he raises himself into a sitting position on the two willow props. Standing one on each side, they straitly examine him, and, if the replies be satisfactory, they depart; but, if not, the corpse is beaten into dust by terrible fiery maces, and then again restored to its original shape.

If the deceased be a true Shia, whose replies have been found satisfactory, his spirit is taken to the “Abode of Peace” near Najaf to await the Day of Judgment; otherwise his soul is taken to the Sabra-i-Barahut, near Babylon, where it undergoes penance, and is purified against the same awful day.

The three following days were days of mourning. On the first day forty-one men were [115] engaged to recite short prayers for the dead, to strengthen him in facing Munkir and Nakir; these are called the “Prayers of Alarm.”

On the second day the grave was visited by relations and friends, and as the latter arrived they recited fatihas, or the opening chapter of the Koran, and ikhlas, or the last chapter but one of the Koran.

They then said, “May Allah give you patience and forgive the deceased, and may He make his position in heaven exalted!” After this they sat down with us and repeated fatihas and ikhlas, placing their hands on the grave.

Then we all stood in a circle, and the Reciter recited a prayer for the forgiveness of all the prophets and saints, and, last of all, for the forgiveness of the dead man.

We finally formed two rows, and thanked our numerous friends as they departed, saying, “Forgive the trouble,” “You have taken infinite trouble.” To this the reply was made, “May Allah show you his kindness, grant you patience, and reward you for your goodness!”

During the three days of mourning all our friends came to offer condolences. When they entered the house they sat down and softly recited a fatiha.

Sarsalamati, they then said, “May your life be safe!” Rose water was poured on the [116] palms of their right hands, with which they sprinkled their faces; and, after drinking coffee, they picked up a portion of the Koran and read, or listened to the professional reciters, who recited chapters in a high-pitched tone. Finally, after partaking of tea and the water pipe, they withdrew to make room for fresh arrivals.

On the third day, the leading mujtahid, Aga Mohamed, came to bring the mourning to an end. He entered, observing the same ceremonial as the other visitors; and, after partaking of tea and a water pipe, he asked the relations of the dead man to fasten up the openings of their shirts which had been torn open as a sign of mourning, and to take off the shawl which the mourners, removing it from their waists, had wound round their necks. The Korans were then collected and a Sacred Recitation was held, at the termination of which all retired and the special part of the mourning came to an end.

Again, on the fourth morning, people assembled at our house, and listened to the Koran being recited. We were then taken to the cemetery, and after saying a, fatiha, I was escorted back to the Mustaufi’s office, where I was welcomed, no longer as a mere assistant, but as the successor to the deceased Mirza Hasan Khan.

In order to show befitting respect for my late [117] uncle, reciters remained for seven days reading the Koran over the grave. On the seventh day lamps and candles were placed on it; and had the deceased been prematurely cut off there would have been a larger number.

The ladies of the family lamented for the first three days with their friends, the same ceremonial being observed as in the assembly of the men; and, on the seventh day, they held a recitation on the grave and then retired. On Friday evenings, on the fortieth day, and again at the end of the year, similar ceremonies were performed. This was, of course, in addition to the festival of the Id-i-Barat. On this day, in honour of the birth of the twelfth Imam, all the souls of the dead receive a barat or bill of freedom for three days; and services are held, and food and sweetmeats distributed to the poor at the graves, which are adorned with flowers.

And thus, O my readers in Europe, respect us for the manner in which we reverence the dead, for whom we wear black clothes for forty days, during which period it is not permitted to use henna or to shave the head. Moreover, mourners do not attend any marriage ceremonies or parties of pleasure until the oldest member of the family takes them to the bath, where they have their hair cut and dyed and their beards trimmed.

Meanwhile a slab of stone had been ordered, [118] bearing an inscription giving the name, family, and age of the late Mirza Hasan Khan, together with the date of his decease. Verses from the Koran and the names of the twelve Imams were also inscribed on it, and when we all visited the grave on the fortieth day, the slab was inspected and then erected over the grave.

Now I have finished this very sad chapter, and, as the poet writes:

Whosoever is born must depart from this world,

As annihilation must overtake every one.

¶ Footnotes

106:1 The translation is taken from Sir L. Pelly’s The Miracle Play of Hasan and Husein, p. 83. ↩︎

108:1 The Arabic form of Gabriel. ↩︎

109:1 Mourners’ tears are collected during the “Passion Play” described in chapter xii., and are considered to be a sovereign remedy for all diseases. The clean handkerchief, in which the tears are gathered, is dried and placed in the shroud of the dead man. ↩︎