[ p. 119 ]

A Mamur should be wise,

A ready talker, sharp witted,

And of independent disposition.

FIRDAUSI.

Towards the end of the winter the Vakil-ul-Mulk, who had been Governor-General for some years, was summoned three or four times to the Telegraph Office, and there were rumours in the bazaar that he was to be dismissed. However, one day there came a private telegram from the Minister of the Interior, which ran as follows: “Alhamdulillah, after much trouble and discussion, your affair has been arranged. The Sovereign, may our souls be his sacrifice, condescends, in consideration of your capacity and efficiency, to order that you remain Governor-General of Kerman and Baluchistan.”

The Vakil-ul-Mulk, who was much pleased, [120] at once gave the Telegraph Master, who brought the auspicious message in person, five hundred tomans, and the following reply was despatched: “The kindness of the Sovereign has exalted the head of this lowly one, who ever prays that the shadow of His Majesty may eternally protect us. Ten thousand tomans, although not a fit present for the royal establishment, are offered by a bill on Aga Faraj Ullah.”

Shortly after this it was decided to send a robe of honour of Kerman shawl to those governors who, by their efficiency and capacity, had been deemed fit to remain in office; for, praise be to Allah, the Vakil-ul-Mulk was not like one of his predecessors, who used to take a present from one man, appoint him to a governorship, and then almost immediately accept a present from a second man, and send him after the first with an order of dismissal.

About this former ruler there is a story which runs that he once appointed a man to a governorship, and this individual, knowing what to expect, bethought him of a plan by which he might be secured in his post. So one day, when the Governor-General was sitting at the window of the Hall of Audience, he saw such a one riding on a horse with his face to its tail and holding a paper in his hand. On seeing this, His Excellency remarked, “What animal is this?” [ p. 121 ] and immediately ordered the individual to be brought to his presence and asked him what was the meaning of such behaviour. Such a one replied, “May I be your Sacrifice! This slave was appointed Governor of Bam; but, knowing that a second Governor would soon be appointed, he sat on his horse looking back towards Kerman and holding the order of appointment all ready for his successor!”

The Governor-General, upon hearing this, rolled over with inextinguishable laughter; and, when he was able to speak, he shouted, “Go, mount thy horse with thy head towards its head. I grant thee Bam for five years.”

To resume, I was appointed Mamur to bear the robe of honour to Hidayat Khan, Governor of Jiruft. This official, who was thus honoured, had recently represented to the Governor-General that, owing to the lack of careful supervision, the Government land at Dosari had become worthless; but that he, to render a service to the State, was prepared to pay one thousand tomans for the property, although he knew that he would lose heavily by it. The Vakil-ul-Mulk, therefore, instructed me to also inquire into this question; and thus I felt that I was indeed a person of consequence when I started on my journey, with a well-equipped abdari on a stout pony, and three servants, one of whom, Rustam [ p. 122 ] Beg, had served the deceased Mirza Hasan Khan as steward for many years.

But perhaps, O my readers in London, there are no abdaris in your country, and it is therefore necessary for me to explain their immense utility. The abdari consists of a pair of large leather saddle bags, faced with carpet, and in these are placed a samovar, a box of sundries, a set of round copper dishes with lids, in which food is carried, a tray, candlesticks, and many other things.

On the saddle bags the servant rides, sitting on a carpet or a Kerman felt of fawn colour, which, when needed, is spread for the meals or repose of the master. Behind is fastened a round leather case, in which all light articles, such as the water pipe, plates, spoons, etc., are carried. Add a charcoal brazier for lighting purposes, which swings on one side, a set of spits, and an umbrella, and you will agree that nothing more is needed than a mule laden with clothes and bedding for even such luxurious travellers as we Iranis, from whom you can learn something in the way of comfort.

Do not enter the tavern without the guide,

Although you may be the Alexander of your time.

The first town we reached was Mahun, where I stopped for a day to see my old friends, who all complimented me on my high position, and [123] begged me to help them in their various cases. From Mahun we rode over a very lofty range, and spent the night close to its highest point in the caravanserai just completed by the noble Vakil-ul-Mulk. The building was of stone, and consisted of a splendid courtyard, round which were many small chambers, and behind were stables for five hundred horses or mules. In short, thanks to the generosity of the Vakil-ul-Mulk, we all passed an agreeable night, whereas, otherwise, it would have been too cold at this season of the year for sleep. Listen to what Omar Khayyam writes:

Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai

Whose Portals are alternate Night and Day,

How Sultan after Sultan with his Pomp

Abode his destined Hour, and went his way.

We next halted at Rain, where a mullah insisted on entertaining me, although Rustam Beg warned me that the Aga was very avaricious. Indeed he spoke the truth, for, just as we were leaving on the following morning, his head servant came to tell me very confidentially that his master much admired my pistol.

I should have replied, “A gift”; but Rustam Beg interrupted me and said that the pistol was only lent me for the journey, and that it would not be right for me to part with it, even as a gift, to the Aga. He added that he himself was [124] responsible for the return of the pistol to its owner. When the Aga’s servant understood that he had failed he was very angry, so Rustam Beg said, “Bismillah! let us start quickly”; and when we had left the village behind he exclaimed, “By Allah! true is the proverb, ‘None hath seen a snake’s foot, an ant’s eye, or a mullah’s bread.’ Praise be to Allah that I did not allow him to flay you!”

From Rain we travelled down a wide valley to Sarvistan, which is noted as being one of the windiest spots in Iran, the saying running as follows:

They asked the Wind “Where is thy home?” It replied, “My poor home is in Tahrud; but I occasionally visit Abarik and Sarvistan.” [1]

Well do I recollect that it was necessary to order the luggage to be piled against the door that night, and, although this precaution prevented it flying open, it was impossible to sleep; and yet the villagers did not consider this gale more than a light breeze! May Allah take pity on them!

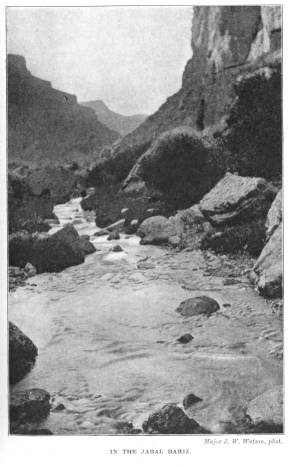

Separating us from Jiruft was the very high range of the Jabal Bariz, well termed “the Cold Range,” as, although it wanted but twenty days to No Ruz, it was very difficult for our party to cross it owing to the deep snow.

[ p. 125 ]

Major J. W. Watson, phot.

[ p. 126 ]

[ p. 127 ]

We stopped for the night at Maskun; about a farsakh off is a famous cave, said to contain gas which kills all living things. Allah knows if this be true, but many witnesses agreed to its being so.

As a mamur from the Vakil-ul-Mulk, I was entertained by the head of the Jabalbarizis. He was evidently of a very great age—more than one hundred years, he said—and his face was like wax; but yet his eye resembled that of a hawk, and, in spite of his poor clothes, he bore himself like a king, and his long white beard was most majestic.

I asked him whether he had visited Kerman recently, as I found his features familiar; but he said that it was more than twenty years since he had left his district. That night, however, he narrated to me that he was a lineal descendant of Sultan Sanjar, from whom he was the thirty-fifth generation in descent; and suddenly I recollected that I had recently been reading a history of that great Seljuk monarch, who, once the Lord of half Asia, was defeated and taken prisoner by the vile tribe of the Ghazz. I also remembered that, in the history, was a portrait of the Sultan, and that that portrait resembled my host closely. The ways of Allah are concealed; but surely there is no other country in which its poor men can claim and prove that they are descended from Sultans.

[ p. 128 ]

The world is nothing,

And the work of the world is nothing.

There was deep snow at Maskun; but yet, a few hours after leaving it, we descended into the valley of Jiruft, where it was already late spring, and it was delightful to see the green crops growing luxuriantly all round the groves of date palms. There were also large numbers of lambs and kids.

We were received by the confidential servant of the Governor, and entertained at a village situated on the right bank of the Halil Rud, the chief river of the Kerman province, which, from its violence, is also known as the Div Rud or “Demon River.”

Close by stretched the ruins of the “City of Dakianus,” [2] covering many farsakhs. Now several ruined cities are termed by this name after a Sovereign, to escape whose persecutions seven Christian youths took refuge in a cave with a faithful dog, and there slept for three hundred and nine years, as recounted in the Koran. Two, farsakhs to the west is said to be the cave in which they slept; but I knew that this event took place in Asia Minor, and that this city was, in reality, the ruins of Komadin, which, so I have read, was the storehouse of the valuables of China and Cathay, and of Hindustan, [ p. 129 ] Abyssinia, Zanzibar, and Egypt. By Allah, I felt sad when I thought of the fate of Komadin, sacked by the accursed Ghazz, who tortured its wretched inhabitants by pouring down their throats hot ashes known as “Ghazz coffee.” May the curse of Allah be upon them!

Three days later, escorted by his staff and attendants, Hidayat Khan came out two, farsakhs from Dosari to a spot fixed by long custom for these important ceremonies. There I invested him with the robe of honour which had been, I assured him, worn by His Excellency the Governor-General, and was therefore, in truth, tanpush or “worn on the body,” an especial honour. I also presented him with the order, by which he was reappointed Governor of Jiruft for the following year. Hidayat Khan was much pleased, and put on the robe of honour before the whole of the assembled Khans and people. He also placed the order on his head and eyes, and reverently kissed it before opening it.

To me he showed great kindness, not only on account of the deceased Mirza Hasan Khan, but also perhaps because I was now mustaufi in his place, and had charge of the revenue of the district. That night I was presented with a beautiful horse of Nejd race; and it was explained to me that an ordinary mamur would only have been given fifty tomans; but that I [ p. 130 ] was to be considered an honoured friend and kinsman, as I was connected with Hidayat Khan through my mother.

Rustam Beg told me, with reference to the gift, that, before the just rule of the Vakil-ul-Mulk, a tyrant had been Governor-General of Kerman, who heard that Hidayat Khan possessed a Nejd mare of pure race. He tried to secure this by sending his Master of Horse to stay with the Khan, with orders to obtain it as a gift; but this plan the latter rendered worthless by giving him butter which had been poisoned with copper, from which he nearly died. Indeed mamur’s butter has become a proverb in the province.

Knowing, however, that the matter would have a sequel, the Khan sent off his family to Shiraz with the famous mare, and never slept in his house at night. By Allah! he was astute, as, a month later, fifty sowars suddenly surrounded his house at night, and, when they found neither the mare nor its master, they tied up and flogged all the servants, sacked the place, and then burned it. This Hidayat Khan saw from where he was living in a nomad tent a farsakh off; and he rode away to Shiraz, and thence went to Tehran, to prostrate himself at the foot of the Throne. But the tyrant was too powerful, and so he lived at Tehran for some years until that wicked Governor died, and he was free to return [131] to Jiruft. My old servant concluded by telling me that the horse presented to me was of that same famous race.

The following morning I inspected the Government property, which, to judge from the quantity of weeds, was not well cultivated; but yet it appeared to be worth at least five thousand tomans; and I was informed that, if properly managed, it would yield crops worth two thousand tomans every year. For a day or two Rustam Beg was constantly visiting the Khan; and, finally, after much hard bargaining, and a threat to return to Kerman, it was arranged that I should receive two hundred tomans for my trouble, and that eight hundred tomans should be offered as a present to the Governor-General, if the Government agreed to the sale of the land at the price suggested.

In the meanwhile the Khan had paid me three hundred tomans which were due to the secretary of His Excellency for the cost of the robe of honour, the pay of the tailor, and the customary gift for the keeper of robes.

As it was very important to reach Kerman before the festival of No Ruz, because to travel during that period, according to our ideas, is inauspicious, I asked the Khan to allow me to leave and said good-bye to him.

Two of my horses having died from eating [132] oleander, which is a terrible poison growing at the first stage, it was decided to snake a double march, and so Dosari was left in the middle of the night, and we rode through the pass with the oleander bushes without stopping, and finally halted at the hamlet of Saghdar. At this stage there was no snow left; but, on the contrary, even the camel thorn was beginning to show great buds.

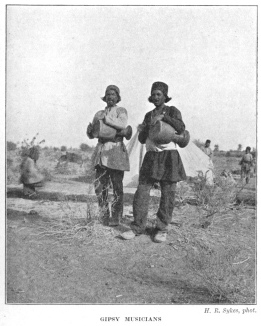

Close to the hamlet was a party of gipsies; and Rustam Beg warned every one to be careful to see that they did not steal anything, when they came round playing their instruments and offering their pipe-stems for sale. These gipsies are the descendants of a band of twelve thousand Indian musicians and jugglers who were brought from India by Bahram Gur to amuse us Iranis; and, even to-day, they alone are the public musicians in most parts of Persia, although I have heard that, in Shiraz, Jews engage in this low profession. However, they are good ironworkers, and also they are experts at bleeding. Now we Iranis know that, unless we are cupped every spring and thereby purify our blood, we shall not retain good health during the summer; and thus their services are much in request for this purpose. In short, they are a vile race, but yet useful to us.

When we had recrossed the Jabal Bariz, we found that everywhere spring was coming; and we decided to march without any halts so as to reach Kerman some days before No Ruz. At Sarvistan, however, we met some men who had been robbed of everything except their trousers by a party of twenty-five Afshar bandits; and so, that night, it was decided to take an Istakhara, or beads, as to whether we should march the following day or wait for further news.

[ p. 133 ]

[ p. 134 ]

[ p. 135 ]

Now every Mussulman carries a rosary with one hundred beads, the origin of which is connected with the marriage of Her Highness the Princess Fatima.

The Prophet, on Him be Peace! declared that he would only give her in marriage to him on to whose house the planet Venus descended. That night all the suitors to her hand were watching the heavens from the roofs of their houses, when the planet moved from its place and descended to above Medina. The white Fatima, too, was watching; and, on seeing this marvel, she called out Allah ho Akbar, or “Allah is Great.” When this exclamation had been repeated thirty-four times the planet began to circle round Medina, whereupon she exclaimed Subhan Ullah, or “Glory be to Allah.” This she had repeated thirty-three times when the planet moved towards the house of Ali, and, finally, she broke into Alhamdulillah, or “Thanks be to Allah,” [ p. 136 ] which she repeated thirty-three times, while the planet stopped over the house of Ali, congratulated him on his good fortune, and re-ascended to its place in the firmament.

These rosaries are consulted in case of danger, and indeed on every occasion. So the opening chapter of the Koran was first solemnly recited, after which I shut my eyes and, thinking intently about the dangers of the road, I took an unknown number of beads in my hand; and then counted them three at a time.

Every one was delighted when it was seen that there were ten beads, as one over, termed Subhan Ullah, is deemed to be most auspicious; and we immediately determined to proceed on the following day. Of course we kept our pistols and rifles all ready, but the route was deserted, although we saw where the Afshars had thrown away part of the loot which was useless to them; and, that night, we all felt very happy that we had been able to prove the truth of our proverb that “a road attacked by thieves is safe,” which means that, after attacking a caravan, the robbers hasten away with their loot, knowing that they will be pursued.

In fact, that night a Captain with thirty sowars arrived, and, a week after our return to Kerman, they brought in seven of the thieves, who were publicly executed in the great square [137] of Kerman, after which the executioner was given a present by all the shopkeepers, this being his perquisite.

During the last stage, the horses and mules understood that they were approaching their home, and moved quite a, farsakh an hour; and, in time, the walls of beloved Kerman appeared, and this my first mamuriat was successfully accomplished. Not only was the private secretary pleased with what I had brought him; but even His Excellency, after listening to the details of what I had done, condescended to praise my diligence and capacity, and remarked to the above official that such a one was a good servant.